The first large-scale organizing drive in the South was to be in 1930 with a focus on textile workers. A. J. Muste on the woeful inadequacy of the drive’s planning.

‘Militancy and Money: Needs of the Southern Organizing Campaign’ by A.J. Muste from Labor Age. Vol. 18 No. 12. December, 1929.

REPRESENTATIVES of international unions R affiliated with the American Federation of Labor met in Washington on November 14 to discuss plans for organizing the South. Such a meeting had been provided for in resolutions introduced at the Toronto convention in October by representatives of the United Textile Workers of America.

Two important recommendations are included among the half-dozen made by the policy committee of the Washington conference and adopted by that conference. The first provides that each international union (there are over 100 of them) shall designate at least one organizer to work in the South. He is to be under the direction of his own international and to organize the workers of his own trade or craft, but he is also to help in the general campaign, especially among textile workers. The activities of these organizers, while in the last analysis under the direction of their own internationals, are to be coordinated by President William Green, assisted by a committee of three to be appointed by him.

The second important recommendation was that President Green should appeal to the labor movement for a fund for organizing textile workers in the South. This fund is to be turned over to the U.T.W., which is to use it in any way it deems fit, for organizing, legal aid, relief, etc., in connection with the Southern campaign. An account is to be rendered to Secretary Frank Morrison of the A.F. of L. to be forwarded to contributing organizations.

At conventions and conferences the chief importance frequently attaches not to the formal decisions recorded but to informal utterances and happenings. The same was true at Washington. The biggest contribution made to the conference was unquestionably in the speeches of the representatives of the State Federations of Labor of Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia and the Carolinas, who had been invited to sit in on the conference. First of all, they painted the conditions in the South as to wages, hours, conditions of work and housing, without mincing words. They showed convincingly and in detail how the wage level, particularly of certain industries in the South, affects the whole South, and indeed the whole nation. Within a single state, for example, building trades’ workers receive almost 50 per cent less pay in mill towns than in cities in other sections where the depressed standards of the mill economy are not in effect to bring down the level of all workers alike.

Ask A. F. of L. to Quit “Puttering”

The Southern labor men went on to say that in the past the “A.F. of L. has done nothing serious in the South.” It had been “hit and miss” work and “puttering.” There arose questions as to whether the present interest in the situation was whole-hearted or not.

They stated flatly that if the A.F. of L. were not prepared to meet bitter opposition from employers, the courts, police, soldiers, the pulpit, the press and mobs, it would be better not to undertake the campaign.

The Southern labor men invited and urged the A.F. of L. to come South with a campaigning force, but they pleaded it must be a large-scale, militant, coordinated campaign. “If it is not to be that, it would be better not to start at all.”

Building Trades for Quiet Methods

There was also a speech by a representative of the building trades. He gave notice in so many words that not too much money for organizing the South must be expected from the building trades’ union. He went on to say that he was against the kind of organizing advocated by Southern labor. He described it as “waving flags and blowing bugles” and buying organizers at cut rates. (President McMahon of the United Textile Workers had suggested that organizers might be gotten to work for a salary of $35 per week plus expenses—perhaps not an unreasonable thing to ask in view of the $20 or less average wage prevailing among the workers to be organized.) The building trades’ leader said. “a quiet business campaign with business methods” would do the trick. That was the method the building trades used. A Southern delegate gently remarked that in the state of North Carolina out of 5,000 bricklayers only 500 were organized. Not so good a showing for business methods! To this there was no reply, at least not in public.

There was also a speech by President Green. It paid a great deal of attention to the autonomy of the international unions, to the fact that no one must presume to give orders to them, and that the rights of the internationals were to be scrupulously respected in the forthcoming campaign. But the main body of President Green’s speech was a passionate appeal for a big campaign in the South. He pledged that he personally would take part in that campaign. He put it squarely up to the international unions to come wholeheartedly to its support. “There will be no peace in the South,” he said, “until the wrongs of the workers are righted.”

Let us analyze now the factors which will determine whether the campaign will be a success or a failure, or at any rate, whether it is to represent an honest and praiseworthy effort or a weak, dishonest, outrageous betrayal of workers who are clamoring for the A.F. of L. to organize them.

The campaign must be the large-scale, militant, coordinated effort for which Southern leaders have asked. Anything else spells failure. The reasons are simple and not too hard to find. For one thing, if an attempt is made to organize piece-meal, to attack a single mill or a few mills at a time, the combined strength of the manufacturers will be thrown against labor at that one point. No matter how long and desperate the fight, production will not be appreciably affected; the other manufacturers can reimburse the struck mills for their losses and labor will inevitably be beaten or worn down. Then the process will be repeated at the next place. That way lies defeat for the U.T.W. and misery and disillusionment for the Southern workers.

In the next place, knowing this full well, having had tragic experience in Gastonia, Marion and in South Carolina, Southern workers will not for long risk themselves on an isolated fight. They must have the feeling of a general movement which sweeps individuals and groups along in its vigorous course, in order to be drawn into the campaign.

Impossible to Localize Campaign

Furthermore, the labor conditions in the South are such that the conflict cannot possibly be confined to a single mill or a single area. Suppose it is decided to work in a particular locality; suppose results are obtained and improvements for the workers are secured—that news will spread like wildfire through the Southern mills. Everyone will want a share in the gains. Thousands of workers are so poorly paid and so irregularly employed that they could hardly be any worse off anyway if they were on strike. “Not all the king’s horses nor all the king’s men” will keep them in the mills if the union makes any headway whatsoever.

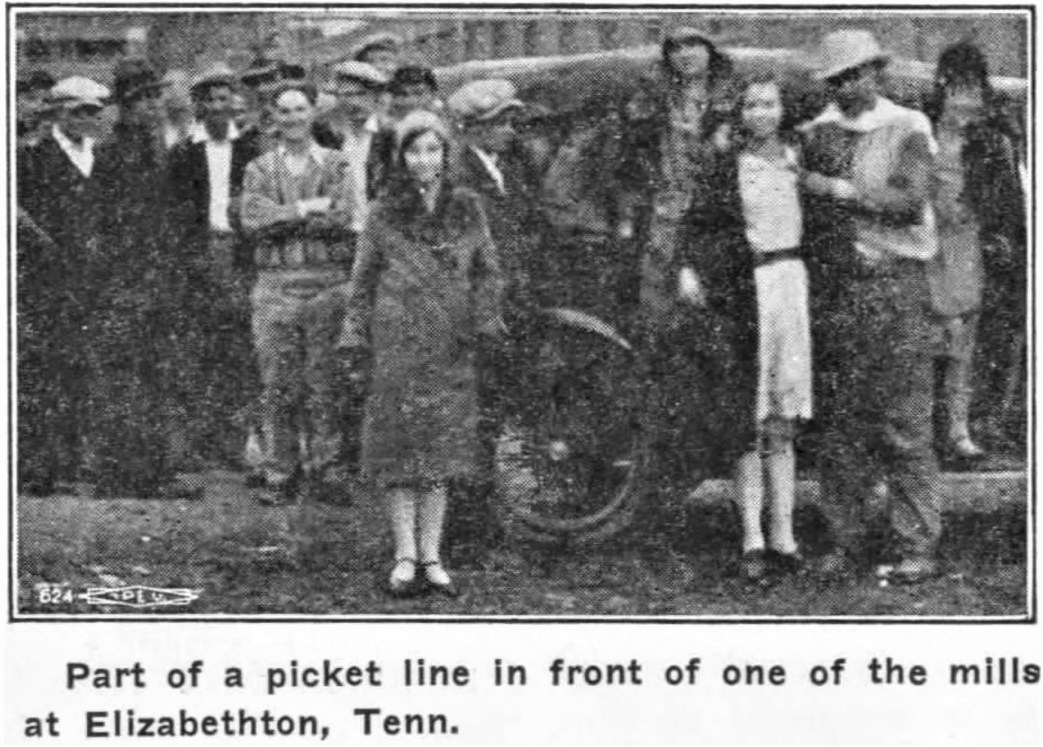

The idea that a quiet, polite, business campaign could or should be carried on fails utterly to take account of the opposition that is certain to be encountered. The Southern labor men made it plain at Washington that the sort of thing which has happened in Elizabethton, Marion and Gastonia will happen again. All the forces of the industrialists and much of the power of the state will be against any serious effort to organize. If that opposition would be disarmed by the union attempting an easy, quiet, one-mill-at-a-time campaign, there might be an argument for pursuing that course. Certainly no one will pay $10 for an article if he can get it for $1. But no sane observer believes that unionism will be permitted to gain a foothold anywhere unless it comes with determination, enthusiasm and power to unionize generally. To take one concrete point. In every strike on some pretext or other, soldiers will be brought in. Bringing in the troops, forbidding meetings, cutting down on picketing, means a lost strike. How will you meet this difficulty? By shooting the soldiers? Hardly. By persuading governors elected by mill influence not to send in the troops? Hardly. There is no way to meet the difficulty except to have so widespread a campaign, requiring the use of so many soldiers in so many places, that the taxpayers will get tired of having their money spent like water in order to keep down the wage level and thus injure and retard the development of the entire community.

The unionist from a skilled craft who argues for a campaign with “business methods” forgets some highly important considerations. Once you have the union well established in the important sections of the country, with money, prestige, experience and power behind it, you may on occasion be able to organize a new locality by quiet business methods, though these occasions are rare enough. No union seeking to gain a foothold in a vast unorganized territory ever accomplished anything by this method, however. None of the big stable unions in the A.F. of L. today established themselves by any other methods than those of militancy, “waving flags and blowing bugles,” getting organizers to work for $35 per week or less. It was not done on a business basis with big business pay. Obviously also a small group of skilled workers may on occasion receive substantial concessions, and employers can reimburse themselves by cutting down on the pay of the masses. When, however, you undertake to raise the level of wages for a whole industry and a whole section of the country, you are up against a very different problem. You cannot get favors then by intentionally or unintentionally playing off one group of the working class against another. Furthermore, methods which will work in organizing small groups of highly skilled workers cannot be applied to the job of bringing in masses of the unskilled and semi-skilled who are not accustomed to the idea of organization, are perhaps poorly educated and are compelled by the very nature of their work to act en masse or not act at all. For the sake of the workers to be reached in the South, as well as for the sake of support from the labor and liberal movements South and North, the issue in Southern textiles must be dramatized, and you cannot dramatize a nice, small-scale, eminently respectable organization effort. The very members of the skilled unions themselves will give support to a dramatic and militant effort, where otherwise they will be left cold and indifferent. It is therefore the exact and literal truth that it would be better, more honest all around, to stay out of the South than to come in with plans for anything except a large-scale, militant and coordinated effort. Here is the first crucial test as to whether the American labor movement means business or is only kidding.

Dollars Not Nickels

Not less than a million dollars should be raised for the special fund to be used by the United Textile Workers for organizing the textile industry. Money is not everything in labor organization work, any more than anywhere else, but without funds this Southern campaign cannot succeed. The size of the fund will be a gauge by which to measure the steam in the boiler. Does labor care enough to give, and to give dollars and not nickels?

We have to face the fact that if the A.F. of L. appeal is to be met only by the internationals as such, there will probably not be a great deal of money raised. There are many internationals, and these often the most progressive and militant, which have troubles of their own, or are small and weak. They will give what they can but it will not be much. The internationals with the most money are often the least interested in the needs of the unorganized, and the most backward about helping the other fellow. It has been demonstrated over and over again, however, that the masses of workers, organized and unorganized, can be reached by an appeal to help their fellows in a labor battle, especially when that appeal has such a poignant, human side as has the appeal of the Southern mill workers. If, therefore, the U.T.W. backed by the A.F. of L.’s call for funds and by the moral support of prominent men in the labor movement, will carry its message back to the local unions and to the rank and file of the workers, money in big sums can be obtained. In addition to the money thus obtained, the morale of the labor movement can be vastly improved if by such a nation-wide appeal penetrating back into the local unions, the movement could be made to feel that it was enlisted in a great humanitarian and labor crusade.

Right Appeal Will Win Response

There are people South and North outside the ranks of labor who will give to this cause. Let the U.T.W. sound, therefore, a nation-wide and convincing appeal to progressives and liberals to pour funds into its organization, publicity and relief fund. If progressive spirits everywhere can be satisfied that this is to be an honest, militant, coordinated and carefully planned effort, this appeal will get a response. Of course, no money will be available if there is to be only “hit or miss puttering.”

Militancy and Money. These are the primary requirements. Certain other factors are scarcely of less importance.

There must be a carefully thought out plan of campaign and a board of strategy which keeps in close touch with developments and adapts the strategy to them. Where are the chief forces to be concentrated? What are the demands which are to be met? On what terms will settlements be made? What compromises are sound? Which ones are betrayals? Is the emphasis to be on reduced hours or increased wages? What kind of publicity and strike machinery is to be ‘set up? What is the program of the union for the industry itself? All these and many more things must be thought out carefully. The days of impromptu, hit or miss organizing, are past.

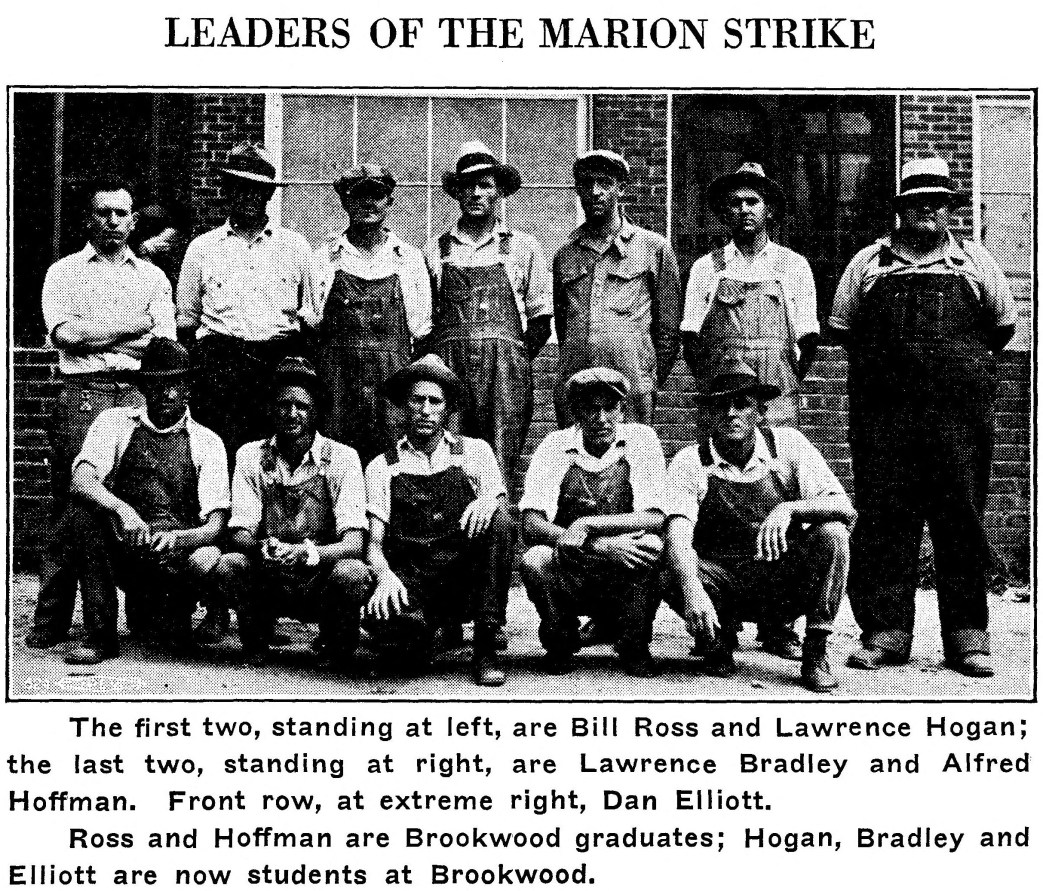

Much depends on the kind of organizers placed on the job. So far as possible they should be Southern men and women. Above all they must be competent organizers. They must be given special training for this job and constantly supervised, guided and inspired from the central headquarters. Ten good men effectively used will do more than 100 chair-warmers or weak sisters. Adam Coaldigger made an important utterance on this subject in the Illinois Miner, official organ of District 12, U.M.W. of A. In an open letter to President Green on How to Organize the South he says:

“If my memory don’t fail me, it also seems to me I saw somewhere that you intend to borrow organizers from their respective International Unions and use them down South. Well, don’t do it, Billy. The boys are all right in their ways, but their ways are not the ways of the South. It is even doubtful if their ways lead anywhere in the North, East, or West. Brother Fitzpatrick was blessed with some of those professional organizers during the great steel strike, and he had more trouble crow-barring them out of hotel upholstery than he had in organizing hungry Hunkies to whom the English language was Greek.

“I warn you especially against using national organizers of what once was the U.M.W. of A., because drinking, card-playing, chambermaid-loving and sleeping in the daytime are still looked upon as capital sins south of the Ohio River, and those are about the only things them boys know how to do expertly.”

Everything that has already been said serves to emphasize still another point, namely, that no divided labor movement will be able to handle the Southern assignment adequately. Here is a task which challenges the brains and energy and devotion of the whole movement. All who are honestly concerned about seeing the job done and a real labor movement in the South established should be welcome to participation in this task. The young, vigorous, militant elements in the movement are challenged by it. They could be fired to a new devotion to the movement if given a chance to share in the great crusade. Without them there is not enough energy to carry the cause to victory. Every great union has been built by its youth; so must this one. If these elements are not used they will certainly be either embittered or utterly disillusioned.

Business Depression and the South

Since the conference at Washington a development which even then merited attention has come to the front. The stock market has crashed. The bubble of Coolidge-Hoover-Mellon prosperity has, for the moment at least, been pricked. Precisely what effect this development will have on the general business situation remains to be seen. It is obvious, however, that Helpful Herbert and the big boys generally would not be conferring so fiercely and proclaiming so insistently that everything is glorious, if there were not some danger of depression, business slump, unemployment and all the rest. Whether there is or is not to be a general and serious depression, it is certain that for the moment the boom is over, and particularly that boom psychology has evaporated. What effect will this have on the Southern campaign?

The merest kindergartner in the labor movement knows that it is hard to organize workers and to call strikes in “bad times.” If there are any people looking for alibis they can use this one for abandoning the Southern campaign, or at least putting the brakes on.

It is the present writer’s opinion that tactics will certainly have to be altered at some points if the cotton industry, for example, is in for a serious depression, drastic curtailment, etc., but that to abandon or seriously to cut down on the Southern campaign would be a grave and unpardonable blunder. If everything that Helpful Herbert and other men of standing have been saying about the importance in this era of mass production of keeping up the purchasing power of the people is true, then one of the reasons why the country is now in difficulties is the low standard of living which has prevailed among Southern mill workers, making it utterly impossible for them to contribute their share to the nation’s capacity for consumption. By that same token one of the best things that could be done to remedy the present difficulty would be to increase wages in the South as well as elsewhere and of course, raise the standard of living, and shorten hours so that there is more leisure to consume the output of our mass production industries. This whole argument about the importance of keeping up the capacity to consume has been made labor’s own. Labor leaders have shouted it from the housetops. They will be traitors and fools if now they fail to hammer it home, or if in this crisis they ease up on the Southern campaign.

If the campaign is slowed up and the impetus gained is lost, then it will certainly be some time before another attempt to organize Southern textiles can be made. In the meantime, employers will make certain concessions, a measure of stability may be achieved by the industry through killing off the least prosperous mills during the depression, and a scheme of company unionism will probably be worked out. Then labor will find itself confronted with another stronghold of welfare capitalism which it is powerless to touch, and the present A.F. of L. unions will more than ever be placed in the position of being a tiny island in the midst of a raging sea of open-shoppery and company unionism.

It is certain also that if bad times are ahead for Southern textile workers, if conditions are actually to be worse than they have been, there will be a tremendous opportunity to preach the gospel of labor and of revolt to them. This opportunity to give them workers’ education, to teach them how it is that a system condemns its workers to such misery in the midst of plenty, must not be neglected. Let us come to them now with a militant and flaming gospel of freedom, and we can develop a labor consciousness in them, can plant deep in their souls hope for a better day and love for the labor movement through which they are to win that day for themselves. That work may not bear fruit over night in the establishment of stable unions, but it will certainly prevent further degradation of the standard of living; it will bring certain immediate improvements for Southern workers, and best of all it will lay the foundations for a militant labor movement in all its branches—trade union, political, cooperative and educational—in that section of the country.

No Turning Back

No, there must be no slackening of the pace. The A.F. of L. has put its hand to the plow. Let there be no turning back.

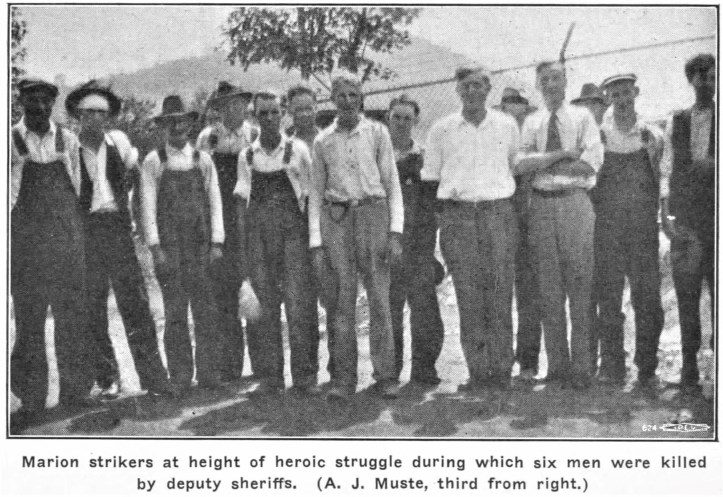

The six men who died in Marion, shot in the back by officers of the law after having been blinded with teargas, members of an A.F. of L. union, 100 per cent Americans, peaceful picketers—they are asking whether they have died in vain. They are asking President Green; they are asking the Executive Council; they are asking the international unions; they are asking the labor movement. The answer is soon to be given. The eyes of the nation are upon our movement as it decides what that answer is to be.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v28n12-Dec-1929-Labor%20Age.pdf