Gurley Flynn on Dublin’s 1913 lockout and one of Ireland’s too numerous ‘Bloody Sundays.’

‘The Revolutionary Flame in Old Ireland’ by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn from Solidarity. Vol. 4 No. 37. September 20, 1913.

The class struggle has struck the battle hour in the Emerald Isle. A week-old strike involving thousands of street car workers in Dublin, Ireland, is challenging the attention of the world of labor. The leader of the strike, Jim Larkin, was spoken of by Tom Mann on his recent visit to New York, as “the Irish syndicalist leader” and through his continual propaganda the unskilled are organizing–a militant working class spirit as distinguished from the older, vague, nationalistic spirit, and a unity between the Irish and English proletarian, have been created. Too long the Irish worker has lost his class identity in a burning zeal for his country’s freedom from the English government, I while the Irish capitalist had no scruples against maintaining commercial relations, helping him exploit his impoverished country for their mutual pocketbooks. “Ireland for the Irish,” is to be realized by the Irish toilers organizing to crush their masters, regardless of their nationality. It is certainly gratifying to know that these Irish workers in their home, country are not of the same calibre as the Irish politician, police and detectives we are unfortunately so familiar with in the United States; that in the hearts of these Dublin strikers burns the same fires of revolt as animated their brothers during the recent street car strike in Milan, the miners’ strikes of South Africa and Michigan, the silk strike of Patterson, New Jersey.

The strike against the Dublin Tramway Company was precipitated by the discharge of 200 men for membership in the “Irish Transport Workers Union.” The union responded by a general strike demanding the reinstatement of their fellow workers.

Discrimination was a last resort after all other means of smashing the union had failed. William Murphy, president of the company is one of the biggest capitalists in Ireland. He owns street car and electric lighting systems, railroads, hotels, steamships, and two Dublin newspapers. Posing as an Irish patriot, he nevertheless accepted a knighthood from the English King. Recently, he held a special midnight meeting of all his employes. He promised them pay for their attendance, and 25 cents increase a week, served them with supper, provided special cars to take them home and finished with the announcement that the directors of the company had voted $500,000 to “smash Larkin and the union.” But the special cars were not used. The men remained in the hall to attend a meeting arranged by Larkin, and there enthusiastically decided to take all Murphy would give but to stick to the union.

The strike has produced intense police persecution. “Just like America,” they comment. Keir Hardie, the Labor member of Parliament, is quoted as saying: “It is a form of action against trades unionism common in America, but I did not expect in any law abiding country like our own, that the anarchist precedent of the United States courts would have been followed.” While it is remarkable that a so-called socialist expects justice from any capitalist government, nevertheless this is an unconsciously humorous commentary on “Free America” and our boasted “superiority.”

In the agitation prior to the strike, our friend and comrade, James Connolly, editor of the “Harp,” author of many pamphlets and well-known in America, was arrested and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment. A meeting was arranged for Sunday, August 31, at Sackville Street, a prominent Dublin thoroughfare, to protest and to enlist general support for the strike. It was prohibited by the police on the grounds of “sedition.” On Friday at the strikers’ meeting, Larkin burned the proclamation of prohibition and announced that the meeting would be held. A warrant was issued against Larkin for “seditious language.”

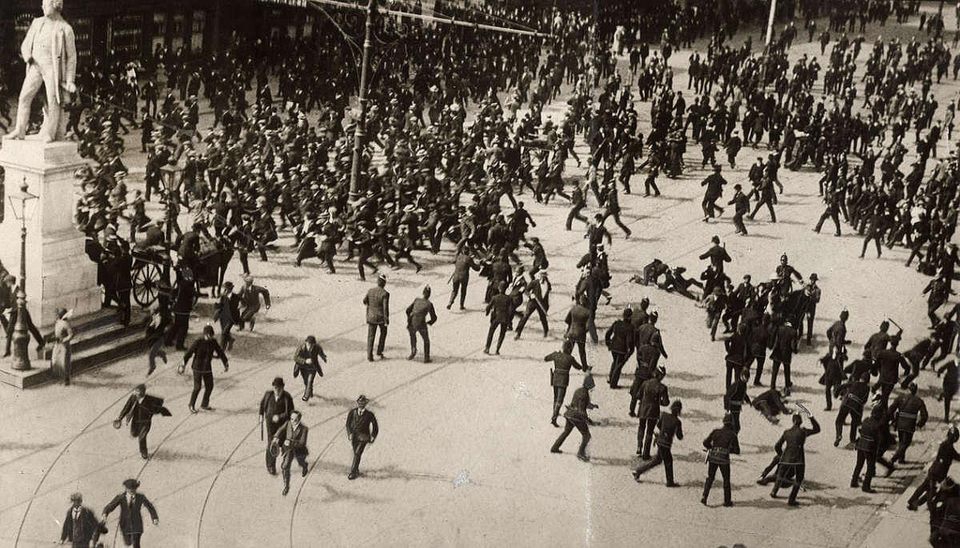

On Sunday crowds gathered at the appointed place from early morning until by one o’clock, the time set for the meeting, thousands were waiting patiently.

Suddenly a white bearded old man who had driven up to the Hotel Imperial a few minutes before, stepped out on the balcony and jerking off his beard announced himself, “I am Jim Larkin. I said I would be here, and here I am.” The police rushed to disperse the cheering crowd and a wild fight followed. Men and women were beaten and trampled on, blood dyed the streets, five hundred were so badly hurt they had to receive hospital treatment, one man was mortally wounded and has since died, and another man killed outright, his skull low of a policeman’s…

[several words missing]

…the hotel, which is owned by Murphy. Cars were wrecked in all parts of the city and police and scabs were stoned from the houses. The attack on the good natured crowd was wholly unexpected and not at all usual in Ireland where the English government has lately made strenuous attempts to conciliate the people of Ireland. It marks August 31 as “the bloodiest day in the history of Dublin.”

The victim of the riot, Nolan, was accorded an impressive burial. Strikers and sympathizers followed the hearse in a procession two miles long. The police remained off the streets during the procession. The description reminds us forcibly of the scenes in Paterson during the funerals of Valentino and Modestino.

This violent attempt to break the workers’ spirit was followed by a lockout of all the members of the Transport Workers’ Union in the employ of the Coal Merchants’ Association. Other marine transportation companies such as the Carrier’s Association are threatening a similar lockout, involving 30,000 men. So complete tie-up of transportation is probable. This has served to add numbers and determination to the strikers’ ranks. They have voted to pay no rents until the strike is over.

Committees have been appointed by the British Trade Union Congress to visit Dublin and offer assistance. While no practical service will probably be rendered, except publicity, it will serve to cement the bonds of fraternity and is a unique event in the history of the two hitherto antagonistic nations–the workers refusing to recognize the old barriers and joining hands across the waters. It occurred only once before, during the British Transport strike of two years ago when the Irish dockers joined under Larkin’s leadership. Larkin, “the man of the hour” in Ireland, has led a busy and adventurous life in the cause of labor. He is the nephew of an Irish rebel who was hung as a leader in the Fenian, movement, by the English government in 1867. He is proud of his family tree–“a man hung in every one of four generations as a rebel.”

Three years ago he was sentenced to three years in jail as a result of agitation against the Cork Shipping Company, but was freed after three months, through widespread agitation. On his release he was given $2,000 by the dockers of Dublin, which he refused to accept and turned over to the organization.

Aggressive and active, he is hated and feared by all middle class, landowning and capitalist Irish, denounced by priests and ministers, but is loved devotedly by all the toilers for his speaking and writing in their behalf.

So here’s success to our brave fellow workers across the sea and a speedy liberation to their spokesman, the daring rebel and good fighter–Comrade Jim Larkin.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1913/v04n36-w192-sep-13-1913-solidarity.pdf