Follow the 1926 British General Strike day-by-day and hour-by-hour with Raymond Postgate.

‘Diary of the British General Strike’ by Raymond W. Postgate from New Masses. Vol. 1 No. 5. September, 1926.

*NOTE: Some of the reports found in this diary may possibly turn out, in the end, untrue. Nevertheless, all are true in the sense that they were current and generally believed at the time.

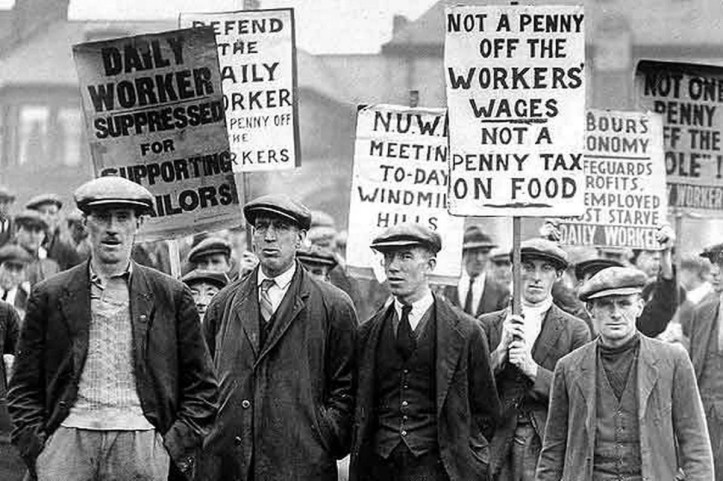

May 1st. Anyway, this is the most astonishing of all May Days. Went down to the Embankment to the procession. We found it standing about and waiting orders all the way from Savoy Street to Blackfriars. A charabanc load of Fascists passed at high speed, in black shirts. They were singing something which made a thin piping noise—some people said it was Rule Britannia, some the Italian hymn Giovinezza. They disappeared amid jeers. Afterwards I heard a few of them got roughly handled when they attempted to seize a banner.

2:30: Still waiting for the signal to march. Banners and carts ceaselessly pour in from Blackfriars. Edgar Lansbury is rushing along the line telling the people something.

They say that what Edgar was saying was that the T.U.C. has called a general strike. I have been up to Bouverie Street, but you cannot get a Star or News at all. The procession has started and is slowly dragging forward, but no one knows the truth. Eric Lansbury shows me a Standard. “There’s no news in it.” I turn it over to see the stop-press: “General Strike Called: The Trades Union Congress has called a general strike.” That’s all. Enough, too. But not enough. When is it called for?

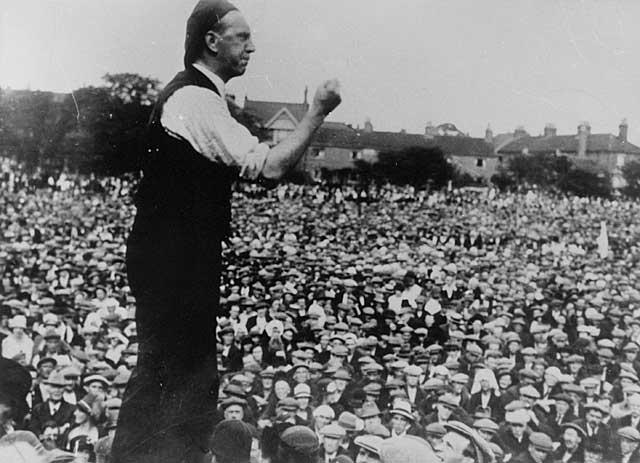

The procession is enormous. We are somewhere near the middle, I suppose. We can’t see either the end or the beginning. It is an unending vista of red banners, black banners, gold banners, picture banners, flapping heavily in the wind. The crowd is fairly friendly till Oxford Street, where there is a four and five deep rank of plump looking men, whores, and nondescripts, who scowl at us. A weak and skinny bearded man boos, but he is drowned in a roar of laughter. I have got a paper:—Strike called for Monday midnight: Transport, Railways, Printers, Builders, Iron and Steel Trades…Bevin’s speech is straightforward and determined: unlike his usual style. The T.U.C. will aid in every way the distribution of food. It sounds as though they meant business.

The procession at last got through to the Park. One feels a little puzzled and astonished: I, at least, doubt whether it will really come off. But all the odds are that it will. Joynson-Hicks and Churchill are obviously in control and want a fight. I met Francis Meynell, who jeered at the possibility of the Congress showing fight. But he withdrew when he saw the paper.

We went home early. Noticed that the police have obviously received orders to be on their best behaviour. Wired G.L. [George Lansbury] to come back from Newton Abbot.

We spent the evening at Ernest Thurtle’s. He thinks Baldwin will climb down on Monday. But we did not discuss the matter long, for we all know nothing. We played bridge.

What a May Day!

Sunday May 2nd. The Sunday papers tell us no more. The Cabinet and the T.U.C. General Council are again negotiating. But how can even Jimmy Thomas find a formula—short of plain treachery? After writing continually to urge the workers to stand together—wondering whether they will ever be determined enough for a general strike—has it come at last? And what the devil will it be like? Has Eccleston Square any plans? enough guts? It is like asking for an elephant or a dragon, not expecting to receive it, and, lo, here it is walking up the garden path.

Went down to Bow, to cheer up Mrs. L. and hear the wireless. No settlement yet, it says.

Monday May 3rd. Still no settlement. I am sending down the usual copy to the printers, mechanically. I think it will be no use. Rang up the Journalists’ Union; it says—keep on with usual work only, until further orders come from the Emergency Committee meeting tonight. Work becomes impossible during the afternoon. Still no settlement. Daisy arranged for us to spend the night with Kath and Mark Starr at Victoria to be near if necessary. Six o’clock: still no news. We shall stay at the Starrs. After dinner, we went to the House of Commons, to see G.L. Brockway was there. He says the Mirror and Sketch have been stopped. The Daily Mail was stopped this morning, by the Natsopa [a printing union] because they would not print a violent anti-Labour appeal. He says the Mail is running with a blackleg staff. G.L. comes out: he says Thomas is almost in collapse. He is making frantic efforts, with Henderson and MacDonald, to “find a formula.”

They are meeting the Cabinet again. There is still no settlement.

We drift back to Starr’s, and talk idly. Before long Bert Hawkins rings up from the Sunday Worker to say that negotiations have broken down. The strike call stands.

A little while later I was talking to Mark Starr about a book, when bells began to ring. The Abbey, the Catholic Cathedral, and other churches, I suppose. We both stopped to listen. There seemed to be an unusual silence for these midnight chimes. The general strike was on, from that minute—the first general strike call since 1842.

All night the bells disturbed me. They ring in Westminster as persistently as in Oxford.

Tuesday May 4th. The streets are a slow crawling mass of private cars. All sorts of curious things have been dug out. I saw one which looked like nothing but a polony on four bicycle wheels, with its works, like entrails, drooping out in front. Some news at the office: The Mail has not been printed. There are no papers, except those printed before midnight. The response to the strike call is magnificent. There is not a thing moving, except a few pirate buses, which circulate carefully round the West End. A dead stop. What can we do? Nothing, except keep quiet. We drift in and out of rooms and exchange gossip. Saklatvala, the Communist M.P., has been arrested for his May-day speech and is out on bail. Somebody says Sheffield is not solid. The T.U.C. will not give us a permit to come out, not to any paper. But Trades Councils, as agents of the General Council, will bring out typed sheets.

In the afternoon we go down with Eric in G.L.’s car to see Mrs. L. again. We drag through to Bow Road. There is no doubt what is happening here. Streams of people walking home from work, a mass of private cars, and a few blackleg lorries. The “mass” pickets are jumping on the front of the lorries and pulling them up. We saw two stopped this way. They leap quite recklessly on the front and often put them out of action. One man has been badly injured doing this. The garage keeper tells us that he has been kept busy all day with broken lorries—smashed up by pierced tanks, punctured tires and so forth. The police look as nervous as cats, and no wonder. Eric Lansbury was half afraid to drive back, without a permit.

At night: the wireless is already broadcasting anti-strike propaganda—stories about the strike breaking down and so forth.

Wednesday May 5th. The streets are much clearer. A few pirate buses are running and a small “circular route” of old General buses. A depot of scabs is behind Electric House—we watched them go in. Some wretched down-and-outs and some arrogant young bloods in Fair-isle jumpers. The roads are slippery and this crowd will break somebody’s neck when it starts driving.

Met G.L. at the office and heard news. Most of the rumours are false. G.L. has not been arrested. Four policemen have not been killed in Bow, though about twelve have been roughly handled. The East End is absolutely tied up. They are not even trying to get the roads open there. There are a few private cars and food lorries with permits running only. Several lorries were overturned, and some ostentatious private cars. The Borough Surveyor’s car was burnt.

The last conversation between the Cabinet and the Labour representatives ran something like this: Churchill (as they entered)

“Have you come to withdraw the strike notices?–”

“No, we–”

“Then there is no reason to continue this discussion”

“Do you think this is Sydney Street again?”

“I have told you we do not propose to continue the discussion.–”

The Government is issuing a mendacious British Gazette, so the T.U.C. has decided to print a British Worker at the Daily Herald office.

A few trains running on the Met and on the Central London Tube. We start walking to Hendon. The pavements are abominably tiring to the feet. All the Hampstead Tube stations are closed.

Hendon: thank goodness for a bath. After dinner, went up to the Co-op Hall. We were immediately put into an executive committee meeting, and after a while I asked whether any arrangements were made for distributing the British Worker. None: so they sent me across to Latham’s to ring up the Daily Herald. The telephonist’s answer was: “Mr. Postgate the police are in possession of the building. That is all I may say.”

Joynson-Hicks and Churchill have really broken loose! I am instructed to write a local sheet to be mimeographed tomorrow, and issued as soon as the assent of the strike committee can be got. It is to be sold round Hendon. Speak for a few minutes to the transport workers in the hall.

Home. Have written it: pretty good, I think. Nellie rings Daisy up. The British Worker is out! The police held on, but the paper was set and put on the machines. A big crowd gathered outside and began to look nasty, especially when the staff shouted that the paper was being printed, but they didn’t know if they could get it out.

Then suddenly the police formed a line and marched off quietly. Not a word of explanation. What on earth…? Were they afraid of the crowd? Has the Cabinet trodden on Joynson-Hick’s face?

Thursday May 6th. No copies of the British Worker here: though there are some of the British Gazette. I rewrite the copy for the Hendon paper and take it up to the Co-op. Hall. I am allowed by a newsagent to have a look at his one copy of the British Worker. 8 pages, size of the old Weekly Herald. Chiefly news. Good.

Nothing to do but write this diary. It is sickening–physically sickening, for it makes you feel ill–to have to be idle at such a time.

Friday May 7th. In the morning we went again to the Co-op. Hall. They still have got no copy of the British Worker, so they are making a type-written paper out of my attempts–a little late. We start to walk to Westminster–five or six miles, I suppose. My left foot hurts. Pavements are much harder than country roads.

They are running a bus service from Golders Green with scabs and some young men in plus fours. Each is protected by a policeman and two specials. This neighbourhood is a loathsome sink of snobbery. I would like to see these people after a Poplar crowd had handled them. By Belsize Park the pickets are surrounded by a clump of what must be almost the most contemptible creatures of humankind.

Camden Town is better. Then into the enemy’s country again, where we bought two British Workers. Obviously better than the first issue, though I much regret to see the General Council is not calling out the gas and power workers. Why not? There are scab trains already running on the Tubes. Damn this impotence.

Heard news: the East End is absolutely immovable. The seamen are out despite their union in Liverpool and the North East coast. The General Council is considering calling out the “necessary services” men, such as food, and letting the Government get on with it. Hang around uselessly, then home to Hendon. Address a meeting at the Workingmen’s Club. They are very short of speakers. I see by an advance copy of the British Worker that the Cabinet are attempting to stop the supply of paper: also that the General Council is indirectly ceasing to arrange for the supply of food. About the Cabinet: this is interesting. They can suppress the paper if they choose under the Emergency Provisions Act, but they choose this indirect method, which gets them all the odium without being certain of the result. For any vigorous action could certainly get paper for the B.W. It suggests they are muddled or weak.

Saturday May 8th. A week gone, and still suspense. Ring Bert Hawkin’s. Police have raided the Young Communist League, the Workers’ Weekly and the Class-War Prisoners’ Aid, and used third-degree torture methods. The French C.G.T. has promised full aid and subscriptions to the British workers.

Up to the Co-operative Hall. Thirty scab buses and one tram have been put out of action. Most surprised to find my speech last night was apparently taken as a hint. A special has been hurt by a stone, but otherwise no casualties are reported. Cannot say how pleased I am to see no more buses running beyond Golders Green, and to think some of those O.M.S. swankers have had a lesson. I must have been more depressed than I realized by the Hampstead gilded youths parading up and down in discreetly safe areas, as this perfectly trifling piece of news cheers me so much.

At night G.L. on the telephone: he says the British Worker is coming out.

The police parade on the first night was to allow a censor to read the paper. Also, that the Archbishops and some representatives of all the Churches have issued a common appeal to both sides the owners to withdraw their notices, the General Council to call off the strike and the Government to continue the subsidy for a definite period. The wireless refused to broadcast this news.

These terms would be a victory for the General Council, and it sounds as though the other side was getting rattled. Canterbury is in touch with the Court. Probably it is the King who has got cold feet.

Sunday May 9th. The British Worker is out, but not the British Gazette. The capitalist sheets look extraordinarily miserable. If you compare one with the other the result is most significant, even to a man who knows nothing of the case. The Sunday Express (a sheet printed on one side only) says “great uneasiness among printers and railwaymen.” “Many applications to return to work being received by the G.W.R.”–not a place mentioned nor a single authentication. The British Worker is detailed, town by town: “Ipswich, Wolverton, Southampton, Newcastle, Liverpool”…and so on, a union report under each. The British Gazette of last night contains an item which I shall keep. It promises “full support” of the Government to “all ranks of the armed forces” for “any action which they may find it necessary to take in an honest endeavour to aid the Civil power.” Any action! Could there be a plainer incitement to violence?

Buses and trams are running almost empty still. Purcell is in charge of issuing permits, at the T.U.C., they say. He is called “Certainly Not Albert.”

Monday May 10th. Another blank day. Down to the office in the morning, saw G.L. No news of importance. The wireless is spreading false news with extraordinary elaborateness. Contradictions are regularly obtained and regularly suppressed. The East End is a solid block still. The police, particularly inspectors, have been misbehaving—violence–at Camden Town and King’s Cross. They are arresting people freely, and especially seizing duplicators. More buses are running–in strictly safe areas. On the phone: Sunday Worker reports a series of train disasters caused by the O.M.S. blundering. Churchill has announced that he will seize all paper to stop the British Worker and print the British Gazette. Up to the Co-op Hall to see if I am wanted. Apparently not. They tell me that the buses went out this morning in a long line down to the Bell, with an armoured car packed with troops at every sixth bus.

Tuesday May 11th. Up to the Co-op Hall. No buses running. There seems no reason why this extraordinary stalemate should ever cease. It has become a life, a habit. Z.Z. estimates that the national loss is about £120,000,000 a day. The Government, at enromous expense, is forcing a few services through, but all production is stilled. Factories are stopping gradually as local materials are used up. There is no transport, for raw materials or finished goods only for food, and the most infinitesimal passenger traffic, intended for propaganda purposes. Even this is dangerous and ill-run: the O.M.S. has caused three disasters already. Three people were killed on a train wreck between Edinburgh and Newcastle, while a fool trying to get up steam at Bishops’ Stortford blew the roof off the station. (One body rescued as yet from the debris.) Gradually the country is being paralysed by a growing numbness, like hemlock poison. Of course it cannot go on for ever. But it can go on a hell of a long time.

Wednesday May 12th. Is this success or ruin? The strike is called off. The wireless says “unconditionally.” The Golders Green scabs are rejoicing and sticking Union Jacks on their buses. On one is a ham bone labelled “The last of the T.U.C.” We walk down to the office to find out. body seems very worried, and there is no information. A full explanation is to be given by J.H. Thomas (the railwaymen’s leader) to the Labour M.P.s.

Later: Thomas stated positively that it was not an unconditional surrender. He said, on behalf of the Council, that this is what happened: Sir Herbert Samuel offered himself as an official go-between. He drew up, in concert with the Council, a memorandum (now published) which gave very considerable concessions–a subsidy to the coal industry for a limited period of time, reorganisation to precede wage cuts (if any), the profits of by-products to be allowed to be counted in to the industry, and several important other protections for the miners. The Premier had agreed to this, but was not prepared to make any public sign until the strike was called off. To do anything else would be to admit defeat. Therefore, to allow the Government to save its prestige, the Council agreed to call the strike off first. Asked whether it could be regarded as certain that the memorandum would be carried out, Thomas answered: “Unhesitatingly: Yes. You may tell your meetings I said so.” The miners have not agreed to it, but their delegate conference on Friday may do so. The Council was absolutely unanimous–Right and Left.

Tonight on the wireless, Baldwin contradicts this. He repeats again and again: “An unconditional surrender.”

Thursday May 13th. The papers and everyone are howling “Unconditional Surrender.” The railway companies, the tram companies, the dock authorities and the printers are rushing forward with huge wage cuts, wholesale victimisations, and humiliating demands such as orders to sign a document promising never to strike. The British Worker is extraordinarily vague and evasive. George Hicks, a member of the Council, on the telephone, swears by the truth of Thomas’ story. The Government has undertaken to carry out the Memorandum. The Council fully satisfied itself that the offer was authoritative, before it acted. Of course, if that is true, the Memorandum represents a very considerable victory. But there is an air of mystery which is most disquieting.

The transport workers, printers and railwaymen are still out. The strikers are angry and disappointed.

Friday May 14th. We are not able to print the paper today. Perhaps it was as well, for by now it seems beyond doubt that the Council has betrayed first and lied afterwards. Herbert Samuel has repudiated the story of an understanding. The Government has repeated its repudiation. Baldwin has put forward his proposals to the miners: they bear no resemblance to the memorandum and are infinitely worse. No member of the Council has come forward with the indignant denunciation, the angry accusation of gross fraud which would be the only answer.

The printing unions–bar one, which is still fighting–have prevented the attack on their standards. Most of the transport workers seem to have done the same. The three railway unions agreement which have secured and appears to prevent victimisation, etc., at the cost of a humble apology and promise never to do it again. In several cases, persecution of trade unionists is going on–there must be many more of which we know nothing. The police have had a final orgy of brutality in St. Pancras and in Poplar.

The Council, not the movement, has failed. It has let its fears overwhelm it. It called off the strike unconditionally, and has wrecked the unity and courage of the workers. Nothing has been done for the miners. No security was gained against victimisation. No effort was made to help the thousands who are in prison suffering spiteful sentences for carrying out the Council’s orders. All–Right and Left–of the Council are in it. Our chiefs were age, indolence, drink and fear.

Z.Z. has an account of the actual surrender, which, he holds, comes from Pugh himself. The Council brought the Samuel Memorandum to the miners, expecting an ecstatic welcome. At this time there was some sort of an undertaking that the Government would accept the Memorandum, if the miners did not otherwise. The miners bluntly refused it and the Memorandum, of course, was void. “Some natural pique” followed, and the Council, meeting for only half-an-hour, decided there was no point in continuing the struggle, and, with incredible levity, called the strike off. A deputation went to Downing Street to convey the message to the Premier. Baldwin sent down to say, “He did not desire to converse with them.” Pugh replied that they had not come to converse, only to announce the surrender. So they were admitted. And that was the end.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1926/v01n05-sep-1926-New-Masses-2nd-rev.pdf