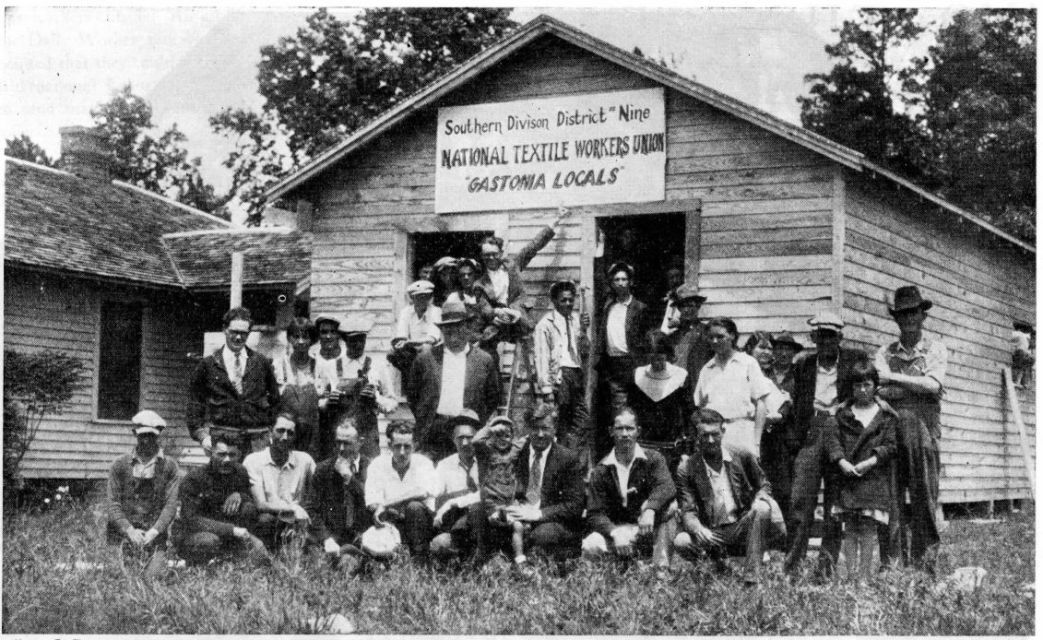

George Padmore on the importance of the Communist Party’s first major campaign in the South. In many ways the textile strikes in North Carolina were a harbinger of the C.I.O. unionization drive of later 1930s as it reached into previously unorganized territory and workers. Led by the T.U.U.L.’s National Textile Workers Union with the Workers International Relief setting up a tent colony and the I.L.D. providing legal supporting, it was an intense and dramatic struggle, death, jail, exile, and death penalty trials followed with C.P. women, playing central roles.

‘Gastonia: Its Significance to Negro Labor’ by George Padmore from the Daily Worker. Vol. 6 No. 180. October 4, 1929.

The acute conflict centered around Gastonia, does not simply express another phase of the class struggle on the American battle front of world capitalism, but also symbolizes in a far reaching and significant form events making for the emancipation of millions of oppressed and brutally persecuted Negroes in the South.

Gastonia is merely the beginning of a series of class battles which are destined to take place throughout the newly industrialized South. We have already seen the workers in action in New Orleans; Elizabethton, Tennessee; Marion, North Carolina; and the various mining sections of West Virginia. Sharper and more bitterly fought out struggles will occur as the class consciousness of the black and white workers of Dixie become aroused by the very nature of the intensive process of capitalist rationalization, which means the worsening of their present horrible standard of living. The condition of these southern workers represent the very lowest among the American working class. The primitive life which both the Negroes and poor whites are reduced to, can only be compared with that of the colonial and semi-colonial toilers in China, India, Africa, the West Indies and Latin America.

It is out of these class conflicts which will sweep over the South with greater rapidity than most of us anticipate, that the Negro and white workers will come to realize their class relations in the present social order. In proportion as they recognize that despite their racial differences, they are both members of the proletariat, will they be able to fight effectively in the common struggles of the working class against the capitalist overlords. This unity of purpose will be the most powerful force in breaking through the age long prejudices between the workers of both races. Herein lies the greatest hopes of the Negro masses in their struggles for self-determination. Let us not deceive ourselves that the eradication of race prejudice will take place over night, but on the other hand, it must come about as a result of the social forces propelling both groups in the same direction and throwing them in the struggle against their class enemy–capitalism.

For years the capitalist oppressors of the South have used the race issue as their most effective instrument to maintain their privileged position. Like the capitalist class of czarist Russia, the white ruling class of Dixie have been able until now to inflame the poor whites against the blacks and in this way withdraw the attention of the workers from the class nature of society. In the czar’s days, the Russian workers and peasants were always made to believe that the Jewish masses were the cause for their poverty, and in this way led to carry out bloody pogroms against a helpless minority. Similarly, the Southern capitalists and their hangers-on–the preachers, politicians, editors and teachers–have taught the white workers that their poverty is caused by the Negroes. With this belief inculcated in the minds of the workers it was therefore easy to incite them into lynching mobs.

Gastonia shows that the workers will no longer be fooled by the deceptive propaganda of their oppressors. Present events indicate the fighting spirit of the masses.

Gastonia has already thrown to the forefront several burning issues. Chief among these, it has dramatized in the boldest aspect the viciousness of the ruling class and the role of the capitalist state during strikes. Thousands of these southern workers who only yesterday suffered from the illusion that the government was their “protector,” today are able to see for themselves that the police, the state militia, and other defenders of “law and order,” are the chief agents of the bosses and mill owners.

Early in 1929, the National Textile Workers’ Union, a left wing organization which grew out of the betrayals of the United Textile Workers’ Union affiliated with the A.F. of L., and controlled by a group of labor fakers who style themselves the Muste “progressives,” invaded the South under the leadership of Fred Beal, a stalwart trade unionist and Communist. After a few months of preliminary work among the workers in the Loray Mill of Gastonia a strike was called. Despite the betrayals of the A.F. of L. unions in the past, the workers goaded by the “stretch out” system, long hours, and starvation wages–which hardly exceeded $12 for adults and $5 for children per week of 69 hours–responded to the appeal of the new left wing union leaders and came out on strike. No sooner had the workers left the mills and organized their picket lines were they confronted with the state militia called in to break the strike by Governor Max Gardner, a mill owner and one of the richest men in the state.

These Anglo-Saxon workers, who for generations have been taught by the ruling class to consider the militia as a special force to keep the “n***rs” in their place, for the first time realized that whenever they dared to demand better conditions that they too would be shot down like dogs alongside of the black workers.

During the course of the strike it became necessary for the union to also organize some Negro workers employed in the mills around Gastonia and Bessemer City. Loyal to their program of full social, political and economic equality for the Negroes, the organizers immediately began to tackle what has always been considered the most delicate problem in the South–the organization of Negro and white workers into the same union. The A.F. of L. has never attempted to undertake this task. Rather, they have always pursued the line of least resistance by leaving the black workers unorganized, and in the few instances where they did organize them they set them apart in Jim-Crow locals. These militant trade unionists, despite their knowledge of the slave traditions of the South, and fully aware of the fact that the business men and their lackeys would exploit the stand taken on behalf of the Negroes, nevertheless refused to surrender their positions. Their heroism in the face of mob law and the lynching appeals of the press will never be forgotten by the American workers. Their courage surpassed that of the abolitionists. Theirs’s was a mission to emancipate not only Negroes but white workers as well from the fetters of wage slavery.

“The Gastonia Gazette,” owned by the mill bosses, issued appeal after appeal to lynch Beal and the other organizers. This paper tried its best to play up race prejudice against these men and women who openly championed the rights of Negroes in North Carolina.

In keeping with its policy, the “Gazette” carried news that the union was controlled by Communists who hated “god” and loved “n***rs.”

The business men and the preachers–a class that can always be found on the side of reaction–called upon the workers to forget the fact that they and their families were being shot down by the gunmen of the mill owners, and to unite with the “respectable” citizens to rid the town of the dirty “foreigners.” Realizing that the appeals were in vain, that the workers refused to be stampeded into a lynching mob, the reactionary forces organized a fascist battalion called the “committee of one hundred” and set out to take the lives of the strike leaders themselves.

During the raid on the strike headquarters by the “committee of one hundred” headed by the police, a very significant thing happened which in itself shows the tremendous spirit of class solidarity between the white and the black workers which Gastonia has already brought into being. This new attitude of class alliance was also reflected in the speeches made by the southern delegates of the recent T.U.U.L. convention in Cleveland.

Otto Hall, a Negro organizer for the textile union, was on his way from Bessemer City to Gastonia on the night of the raid in question. The white workers realizing the grave danger to which Hall was exposed if he happened to get into Gastonia that night, formed a body guard and went out to meet Hall and warned him to keep away. They met Hall two miles out of town and took him in a motor car to Charlotte where they collected enough money among themselves to pay his railroad fare to New York. No sooner had Hall embarked on the train a mob broke into the house where he hid before his departure. It was only the timely and prompt action of these white workers that saved the life of their Negro comrade.

One can easily imagine why these fascists were so anxious to get hold of Hall. As a Negro it would have been very easy to accuse him of some alleged crime and thereby “justify” their action of lynching him. After that, the class nature of the Gastonia struggle would have been diverted into one of a racial issue leading to the wholesale lynchings of the white Communists, the champions of equality for the blacks.

The Negro workers, together with the white workers of America, must answer this challenge of the capitalist class by mass protest action until the revolutionary fighters now on trial at Charlotte are freed from the clutches of the mill barons.

We can already deduct several valuable lessons from Gastonia in relation to the working class in general and the Negro in particular.

(1) The struggle immediately brings on the order of the day the right of the workers to defend themselves. This must be the central issue for us, for as indicated, the workers will engage in more and more such class battles in the near future, during which fascist elements such as the “committee of one hundred” would be mobilized against the strikers. We cannot surrender the right of self defense, otherwise we will be simply inviting wholesale massacre of the working class.

(2) Race prejudice is not a geographical feature of American capitalist society. It is everywhere, although more bitterly entrenched in the South, because of its semi-feudal remnants. As the process of industrialization proceeds and the Negroes and poor whites are drawn from the rural communities into the industrial centers they will be forced to discard the ideology of the past and to orientate themselves to their new environment. This process of urbanization will bring them together and out of these contacts they will learn to recognize that both groups are the slaves of the bosses. They will further learn through their everyday experiences that the employers foster race prejudice in order to keep them apart and thereby exploit them more easily.

(3) The new class battles which will increasingly break out will necessitate the application of new methods of class warfare. We have already realized that the antiquated Jim Crow craft unions fostered by the A.F. of L. must be displaced by new industrial unions under the militant leadership of the Communists and the left wing T.U.E.L. Every battle will present us with new lessons in class tactics and methods of struggle. We must therefore be always on the alert to recognize our weak and strong points. Rigid self-criticism must be indulged in, in order to immediately correct our mistakes and steel our fighting forces so that all advantageous positions gained by the workers will be consolidated.

(4) A systematic ideological campaign against white chauvinism must be carried on among the workers as well as within the Party, ranks. There is still a tremendous underestimation of Negro work among some of our comrades. Up till now too little serious attention has been given to this phase of our activities. The T.U.U.L. convention marks a new effort, which, however, must now end merely in resolutions. The large Negro delegation shows that we are capable of winning the black workers to our banner if we ourselves carry on systematic work among them. These Negro workers, as pointed out by the Comintern over and over again, represent revolutionary potentialities which it will be criminal for us to neglect for the social revolution. We must therefore intensify our work among them, and draw them not only into the new unions but also into the ranks of the Party.

(5) We must popularize our slogans of full social, political, and economic equality for Negroes more than we have done in the past. The most effective means of doing this is through our press, especially the “Negro Champion,” which should be developed into the mass organ of the Negro workers. In districts and centers where large groups of Negroes are employed especially in the centers of the basic industries special leaflets and bulletins dealing in a concrete way with their everyday problems should be distributed at regular intervals. The Negro press can also be utilized to a greater extent then some of our comrades recognize. In order to do this the Crusader News Service should be subsidized.

Because of the peculiar position of the Negro petty-bourgeoisie and intellectuals, they too, are compelled to support our slogans of equality for the Negro workers or else expose their reactionary role before the masses. Experience has taught that these slogans of equality mean more to the Negro working class than to the black bourgeoisie and its middle class hangers-on, because they already enjoy a certain privileged position in Afro-American society, by playing second fiddle to the powers that be.

As the struggle assumes sharper class lines the so-called Negro leaders who still befuddle the black workers and peasants with radical propaganda such as Garvey’s “Back to Africa” slogan–a form of black Zionism–will be compelled to show their true colors and in this way expose their counter-revolutionary position before the Negro working class.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v06-n180-NY-oct-04-1929-DW-LOC.pdf