The story of working class fighter Milka Sablich who came of age in the 1927-8 Colorado Coal War.

‘’Flaming Milka’s’ Story’ by Grace Lumpkin from New Masses. Vol. 3 No. 10. February, 1928.

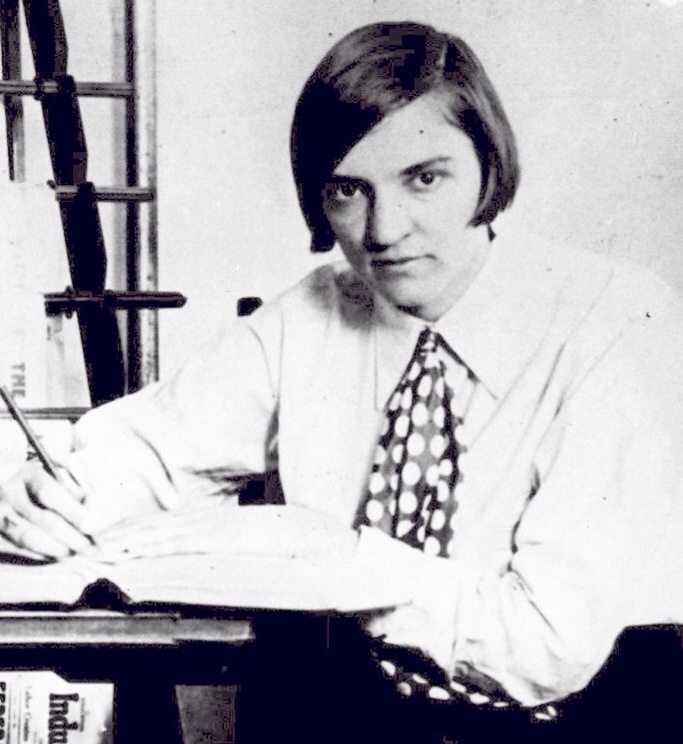

The story of Milka Sablich, “flaming Milka” of the Colorado Miners Strike, is the story of two canyons, of the mines and the workers in them.

In my mind the story takes the form of a movie. It begins a long way back, in the sixteenth century when young Hernando Cortez was conquering Mexico. The picture shows the haughty Spanish adventurers who were sent to Colorado by Cortez to find the gold reported to be there in immense quantities. The adventurers have Indians guiding them and the Indians are chained at night to keep them from running away. The Spanish gentlemen are courageous and very young like their leader Cortez. They are romantic and not without a certain appreciation of beauty. When they reach the canyon that was later to be named Delagua, look up its valley, and see at the end two rounded peaks covered with snow, they follow the lines of the ridge and trace in their imaginations the outline of a woman’s body. They name the peaks at the end of the canyon “Pechos de la Virgin” or “Breasts of the Maiden.” Later the picture shows them getting down to more practical matters. They set their Indians tunnelling for gold, using powdered limestone for blowing away the rock.

The Spaniards fade from the picture and many years later comes thin Rockefeller whose pious eyes are not lifted to the beauties of Pechos de la Virgin. Instead of a period of contemplation of beauty there is at once much travel through the canyons—bustle and hurry. Machines are brought in, tipples constructed and shacks for the workers built. Then the workers themselves come crowding up the canyons—Slavs, Italians, Mexicans, Americans—negroes and whites. The shacks and tipples come to life.

On the screen the picture of many workers slowly fuses into a conglomerate mass of faces, and out of this emerges a four-year girl standing with her father in front of a shack at Forbes. We watch the child Milka and her family when they move from Forbes to Trinidad and settle in a larger house. The child grows and we see her doing all the things that other girls do. One or two things stand out. One day she looks in the chest her mother had brought from the old country and smiles with a touch of American superiority at the colorful Slavic peasant dresses.

If we are clever we look into the girl’s mind and catch the gradual growth of understanding of the fact that when fathers go down into the mine it doesn’t always follow that they come up alive. We watch Milka’s mother straining her eyes up the canyon if her husband doesn’t get back from work on time. There are flashes of miners’ wives, cooking, sweeping, sewing, but always with a curious alert expression underneath their stolidity, as if they are forever listening. And one day they hear the sound. We see the steam rise from the whistle at the mine, rise again and again. Then a shriek from a shack (could the instruments in the orchestra do this?)—another shriek, moans, and after that a hopeless droning wail coming from the throats of women as they run from their houses and meet in the center of the canyon to surge up through the valley toward the mine—toward the whistle—because the whistle means there are some dead men up there.

We see Milka going with her mother to the tipple, helping her mother climb up toward the mine with the other women. They wait. The death list is called. Milka sees the relaxation on faces of those women who learn that they have no special case for sorrow—this time—and on others the strained, hideous grief pulling down the lower jaws to let out the sobs.

But in the fortunate women’s faces the brief gladness dies down. As they go back to work, or help with the funerals we see that second sharp-eared person, hiding and listening inside the everyday wife or mother or daughter.

After the death of Milka’s mother we watch the girl on the screen as she takes on some of her mother’s work, keeping house for her father and sisters, because her sisters work outside and somebody has to keep the house going.

There is a short sequence showing Milka on her nineteenth birthday—it’s 1927 now—putting some extra touches to her red woolen dress that is in its third year. She wears the dress to a dance and again the next day after the accident in the mine when she goes with other girls to the morgue where the bodies of three boys they had danced with the night before are laid out.

They come out of the morgue and stop down the road to watch the company police taking an I.W.W. organizer off the company property.

Later one of the young miners asks Milka to go to a meeting with him. We see that she is bored with the idea of a meeting. She doesn’t like listening to people talk from a platform. But because she likes the boy she goes along. The speakers tell them a strike is going on, and they want the women to volunteer for the picket line. One man asks all the women who will go to raise their hands. Milka’s hands lie in her lap. But when she sees her sister, Santa, and some others volunteer she puts up her hand, too.

Then we watch a strenuous life begin for Milka. We see her wearing the red woolen dress, because it is the only warm one she has, serving coffee and bread to pickets at four o’clock on dark mornings in the I.W.W. Hall. She speaks at Walsenburg and other places. She leads the picket line at the Ideal mine. Here the deputies gallop on their horses along the road by the picket line and lasso the pickets. They get their ropes over Milka’s head again and again but with her strong hands she tears off the rope each time and goes back to lead the line again. Then the deputies charge the pickets. On the screen we see the horses come rushing down on the strikers, the lines parting. A deputy spurs his horse toward Milka and catching her wrist, drags her along the road by the side of his galloping horse for more than fifty yards. When he drops her on the ground and rides on, we see the pickets lift her up. An automobile comes and they take her to a hospital.

In two days she is out on the picket line again. This time the strikers are going to storm the Delagua mines. The men up there are the only workers who are not striking because the pickets who have tried to get into the canyon before have over and over again been repulsed by the state police and gunmen hired by the company. On this day the pickets are determined to reach Delagua mine Number Three where all the workers gather in the early morning before they are sent to the different mines at the head of the canyon.

The pickets are waiting at the foot of the canyon, not far from Ludlow. We see the boy who will lead the picket line with the American flag in his hands, and beside him, Milka. We can’t make Out their faces because it is still dark, but we look behind them and feel the gray restless shadows of the pickets waiting for the signal to march.

In the picture we move up the canyon and follow the railroad track to the first bridge across the dry arroyo, and make out a road that runs beside the track. Further up the picture shows us dark mountain peaks lining the sides of the canyon, like rows of huge blackened faces staring at each other curiously.

Down the canyon again a flash across the screen shows us that on that first bridge, scarcely a mile from the pickets, are massed the company guard, waiting for the miners who are coming on, led by Milka and the boy with the flag.

As the pickets get to the bridge Milka and the boy suddenly dive under it, through the arroyo and up the other side with the workers following. When they have gotten safely out of the way, Milka sees that the guards have gone down into the arroyo and cut off half the pickets. She goes back, and calling them to join her on the bridge leads them across, then waits behind to see that all of them are over. She starts to follow them, but she is too slow. The guards surround her and in a moment they have her handcuffed. The steel is so tight on her wrists she faints. But the pickets have seen. They rush back, and force the guards to take the handcuffs off and give Milka up to them. Her comrades carry her up the road, revive her, and she takes her place again at the head of the line.

All the way up the valley we see the mine guards with revolvers and clubs gather to fight the pickets who are armed only with fists–and at every spot the pickets push and fight their way through, forcing the guards to get into their cars and drive ahead to make another stand further up the canyon.

When light begins to sift down into the valley, so the pickets can see their way a little, an engine comes up the track and running evenly with the pickets on the road blows steam continuously into their lines and envelopes them in it so they must walk blindly in a fog, with steamed clothing clinging to their bodies. They sing Solidarity Forever, but the engine whistles shrilly. The leaders strike out from the road and climb the side of the mountain a little way, the pickets following. They scramble over rocks, through gulleys and around sharp points of stunted cedars and pines. The gunmen meet them there, too, and handcuff Milka again–they want the leaders but the pickets run to rescue her, sending down small avalanches of rocks and gravel. They struggle with the guards and take Milka again. With her at their head they make their way along the sides of the mountains getting closer to Delagua Number Three and those workers who are up there waiting to go to work, or if the pickets are successful–to join the strike.

They reach the mine. A car stands there and two strikers lift Milka to its top. She begins speaking and the Delagua miners crowd around. The deputies use their revolvers and clubs, but the pickets close up their ranks and sing Solidarity Forever. With the five-mile march behind her and the fighting, Milka is worn out. She sways up there on the car, but keeps on talking, hammering into the men that they must come out–solidarity forever and the union makes us strong.

A gunman grabs the flag from the boy who has led the march. He shakes the flag at Milka, telling her he is an American Legion man and the pickets can’t have his flag. Milka turns to the pickets and asks those who are American Legion men to raise their hands. The hands go up. Milka turns to the gunman and says, “It’s our flag, too, and we’re going to keep it. But even if none of us were American Legion we’d keep it. We’re Americans same as you and we’ve got a right to our flag.”

We see that Milka is weak and as she closes her eyes and sways up there on the car we want to reach out our hands and catch her before she falls. But on the screen the strikers around the car are watching her, and many hands reach up to help her down.

The head deputy comes up and orders the pickets to leave. They point to Milka lying on the ground, just opening her eyes. The deputy asks Milka if she will lead the pickets away. She says “Give us our flag and I will.” A sullen gunman gives up the flag to the deputy. Milka is standing now, ready to go. She and the boy, with the flag in his hands again, start off, the pickets following. But they do not go alone. The Delagua workers have joined the strike.

In my mind it makes a movie, the story of the strike and Milka. It has the flag, the heroine, fights, many of them, rescues and counter fights. But it’s a movie that can’t be finished. We might go on and watch Milka in jail for five weeks, refused bail. We might show Columbine and those six workers killed and others wounded while officials of the mine and the company look on. But that wouldn’t finish the movie, and it wouldn’t finish Milka’s story. Because Milka is not only herself–she is a worker and her story is theirs.

So the movie must be cut off, without a proper climax–without a happy ending. Because there are many other reels to be taken before the story is finished.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1928/v03n10-feb-1928-New-Masses.pdf