The final letter from Liebknecht finds him angry and defiant, reporting on the farcical trial of the Communards, that ‘victory’ in the war has only led to misery and repression fro German workers, and ends with an appeal for American comrades to come to the aid of the Commune’s refugees gathered in London living in poverty and distress. The complete letters here.

‘Letter from Leipzig, XXV’ by Wilhelm Liebknecht from Workingman’s Advocate (Chicago). Vol. 8 No. 6-7. November 25-December 2, 1871.

Leipzig, October 8, 1871

To The Editor of WORKINGMAN’S ADVOCATE:

The “sentence” passed upon the Communalist prisoners by the privileged murderers of Versailles is a heavy blow upon the arrangers of this bloody judicial farce. In fact it amounts to their own condemnation.

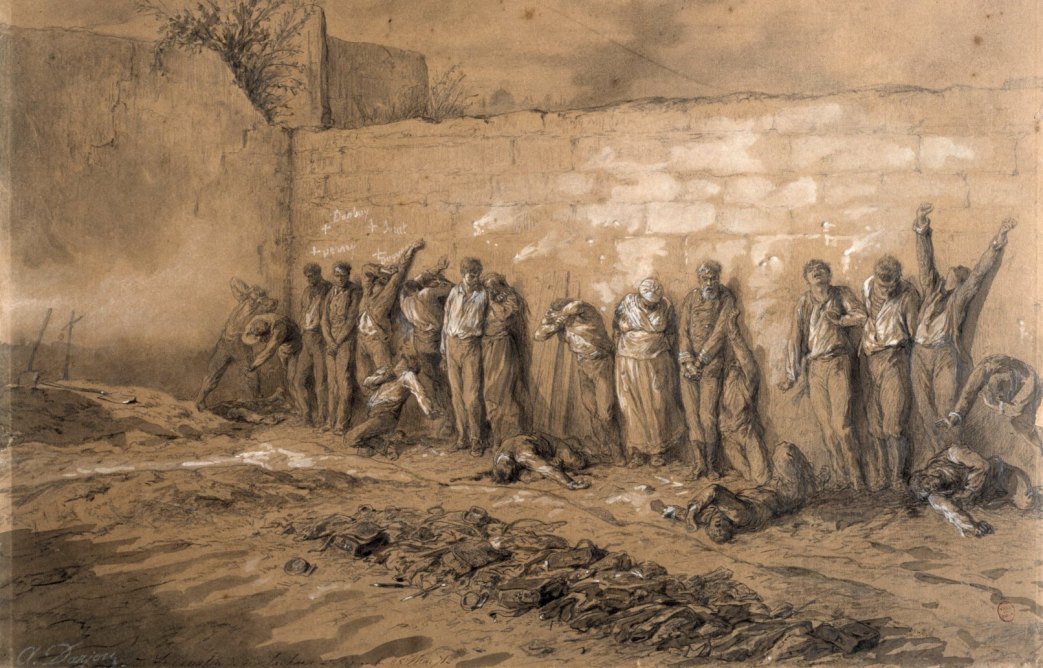

The court martial was not instituted to try, but to condemn, to kill; and yet with the best will, after having used all means of unscrupulous infamy–forging, false witnesses, bullying of the accused–it could not bring home the common crimes of assassination, incendiarism and plundering to any of the doomed victims and could not pass sentence of death upon more than two of the accused, one of the two being notoriously an agent of Mr. Thiers, so that his condemnation at all events is only a comedy, to save appearances. Now, the men that stood before this court martial were the most “guilty” of the Communalists, so far as we can talk here of guilt; and if out of these most “guilty” a court martial like this could in earnest find but one deserving the penalty of death, what must we think of the slaughtering, during the last St. Bartholomew, of 20,000 men, the “guiltiest” of whom were not as “guilty” as the least “guilty” of the men M. Thiers’ packed court martial could not sentence to death. Why have they been murdered, downright murdered, murdered in the most literal sense of the word, these 20,000 men, women and children?

M. Thiers, the newly named “President of the Republic”–it was a good piece of fun that!–is, luckily for him, not burdened with that troublesome thing called conscience, he would have to share his Prussian friend Bismarck’s ugly complaint: “sleepless nights.” Though for the present Mr. Bismarck seems to have got a respite, all the reporters that have seen him lately mentioning with remarkable unanimity his looking uncommonly healthy and cheerful. Perhaps the unanimity is too great not to excite some little doubt. Perhaps the big statesman has his reasons to be considered in good health and spirits, the Austrians not being inclined to enter into an alliance with a sick man, and careworn too; and newspaper men are the most obliging people in the world. For my part, I do not quite believe in Mr. Bismarck’s cheerful looks, unless he be a virtuoso in hypocrisy, or a model of Christian meekness. Certainly things are not, for him, satisfactory at all. The “new empire,” instead of acquiring strength, is daily losing ground in the heart of its police-ridden inmates; the Prussians themselves, who, like eels, are used to skinning, begin to grumble. They had been led to hope that after this war, which to be sure would be the last, the burdens of taxation would be diminished, and political liberty increased; and now they find that a new war is looming in the nearest future, and that in the last war, the people, instead of fighting for their own benefit, had only fought for despotism and militarism. Is the same to be done again? Are they always to move in the same cercle vicieux? And terrible indeed have been the sacrifices and sufferings the people had to bear, not to talk of the dead, the maimed and the invalided. One instance may exemplify this: Berlin, the capital of Prussia, is, perhaps with the exception of Cologne, the richest town of the Prussian monarchy. Well, according to a little paragraph published by the Berlin town authorities, fully three-quarters of the reservists and landswehr who served in the late war have applied for relief, they now being without any, or sufficient means of subsistence! Add to this the rising rents, the dearness of food in consequence of a defective harvest, and you will not wonder at even the Prussians beginning to grumble. Far deeper, however, is the discontent in other parts of Germany, where the inhabitants are not accustomed to the new Empire, which are the old ways of Prussia; the new Empire being, as you know, nothing but enlarged Prussia. Here in Saxony, the friends of the present order of things are much less numerous than half a year ago, and in another half year they will have to be looked for with the lantern of Diogenes; it is still worse in Bavaria, Württemburg, and Hesse, which were the last to be forced into Prussia’s arms, and the inhabitants of which are hostile to the Bismarckian unity. Of Baden nothing can be said yet. This unhappy country, once in advance of the rest of Germany, has in 1849 been treated so terribly by the Prussians–2,000 killed in battle, 20 shot by sentence of court martial, 20,000 thrown into prison, and 30,000 families driven into exile–that political life is still extinct, and a little handful of reactionists, “national” or “popish,” have the field to themselves. This will not continue much longer. A day will come when the people of Baden will awake; and that day will be a day of stern reckoning! So, wherever we look in Germany, there is no spot to be found where satisfaction with the new Empire dwells. And what is it that keeps Empires together; that enables them to withstand the attacks of enemies, to rise more powerful after defeat? Physical force it is not. Where was more physical force, where a stronger government. where larger armies, than in the old Roman Empire, or in the Empire of Napoleon I? And have both these Empires not been shattered like glass? But let us look at another picture. There was a free country once, attacked by a mighty host of its own unworthy sons. The government was unprepared, without an army, while the enemy could bring a large force into the field, and was backed by some of the greatest powers. But the people had an interest to support the government, because they had an interest to preserve the commonwealth, which guaranteed their rights and promoted their welfare. Volunteers rushed under the standards by the thousands and hundreds of thousands. The first army was beaten by their better organized adversaries; a second army shared the same fate; a third army also. Still the people stood by the government: fresh warriors rose and learned victory from defeat, until the rebellion was crushed. You know the country of which I speak’ and I know that my country could not, in the shape of the present Empire, survive one single decisive defeat. While a free country has its powers called forth by defeat, a despotic country is overthrown by defeat. Of that Mr. Bismarck is conscious. He is well aware of the growing unpopularity of his “creation:” he does not harbor the foolish idea that the German people would rise for the defense and maintenance of that large prison–the Prusso-German Empire. Its existence depends on the fate of its armies. One decisive battle lost, and it falls to pieces, just as the French Empire fell after a month’s campaign: just as all former and future soldier empires did fall and will fall. Mr. Bismarck nurtures no illusions on this point, and since making Germany free would for him be suicide, all the thoughts must turn on preventing defeat. And for this there are two ways: augmenting the army, and securing allies. The former he is doing: the latter he is trying to do. Trying in vain–that may safely be foretold. The interviews at Gastein are a humbug, nothing else. Common fear of Socialism will cause a short rapprochement between the two Emperors; but as soon as other events throw the dangers of the “International” in the shade, Austria will use the opportunities offered by these events. It has now come to light that last year only the quick overthrow of the French Empire hindered Austria from declaring war on Prussia, the Austrian army not having been ready to take the field at the beginning of the contest. Since then the Austrian army has been greatly improved and increased; a new war would not find it unprepared. It is true the two Emperors have kissed each other tenderly–but once before they have done it, with perhaps more fervor, in the autumn of 1865. Nine months later Austria was throttled by a chivalrous Prussia and half dead, kicked out of Mother Germania’s doors. Can that be forgotten, at Vienna? Scarcely. And if it were, at the next chance of revenge, the memory would revive. I really doubt whether Bismarck is as cheerful as newspaper reporters tell us.

What I said about the issue of the strike of the Berlin Masons, is in contradiction with the last proclamation of the Strike Committee. However, what I stated is strictly true. The fight was about the ten hours, and the ten hours have not been gained. That is undeniable, and that settles the point. That in some places higher wages are paid, now than before, has nothing whatever to do with the strike. The Berlin Carpenters have effected a compromise with the masters; they have an assurance of wages. The Cigar Makers Strikes still continue at Halberstadt, Hanau and Offenbach. At Hanau one of the largest masters has yielded, and it is to be expected, that the others will follow his example. At Barmen the metal workers are still on strike, while the workmen of other branches have come to a compromise. The Barmen strike is handsomely supported by the workmen all over Germany. From the English papers you will have seen that the German workmen enticed to Newcastle have made common cause with their English brethren. This fact will show you how deep in Germany socialist ideas have penetrated into the masses, so that even those who do not properly belong to our party, as is the case with these workmen, are yet impregnated with our ideas.

Letters I received from Geneva and London speak of great distress amongst the Communist refugees crowding there. We are already over burdened, yet shall do what we can. But could not our American brethren do something? If the WORKINGMAN’S ADVOCATE takes the matter in hand, I doubt not but you will soon be able to transmit a substantial token of international fraternity to the General Council of the I.W.A. 286 High Holbourn, London.

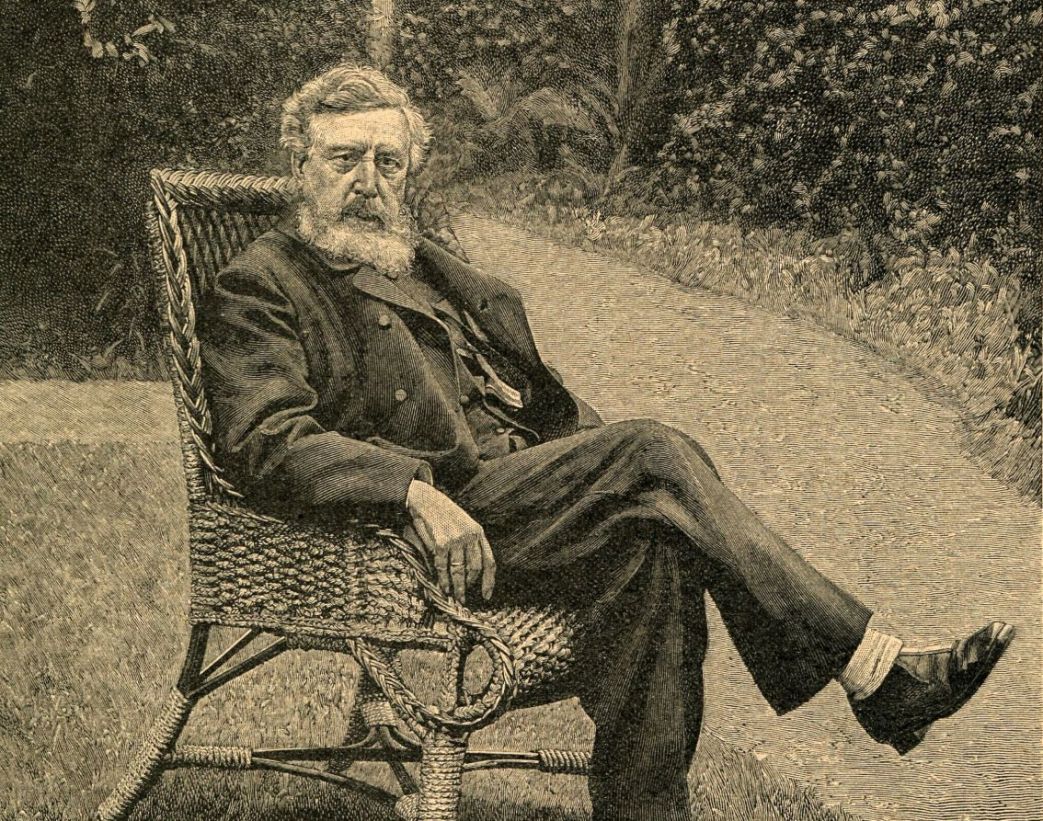

The Chicago Workingman’s Advocate in 1864 by the Chicago Typographical Union during a strike against the Chicago Times. An essential publication in the history of the U.S. workers’ movement, the Advocate though editor Andrew Cameron became the voice National Labor Union after the Civil War. It’s pages were often the first place the work of Marx, Engels, and the International were printed in English in the U.S. It lasted through 1874 with the demise of the N.L.U.

PDF of issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89077510/1871-11-25/ed-1/seq-3/