Leonard Abbott introduces us to the poetry of Edward Carpenter. Carpenter’s 1898 collection ‘Love’s Coming of Age’ had such a profound impact on a generation of radicals, including in the Socialist movement to which Carpenter belonged. Former curate turned socialist activist and academic, Carpenter joined the Social Democratic Federation in 1883, soon leaving with William Morris to form the Socialist League and was a fixture in the ‘bohemian’ utopian socialists of day. Gay and living openly with his partner, former iron-worker and fellow socialist George Merrill, for over three decades. Both were pioneers in the politics and actions of sexual, gender, and gay liberation.

‘The Poetry of Edward Carpenter’ by Leonard D. Abbott from The Comrade. Vol. 1 No. November, 1901.

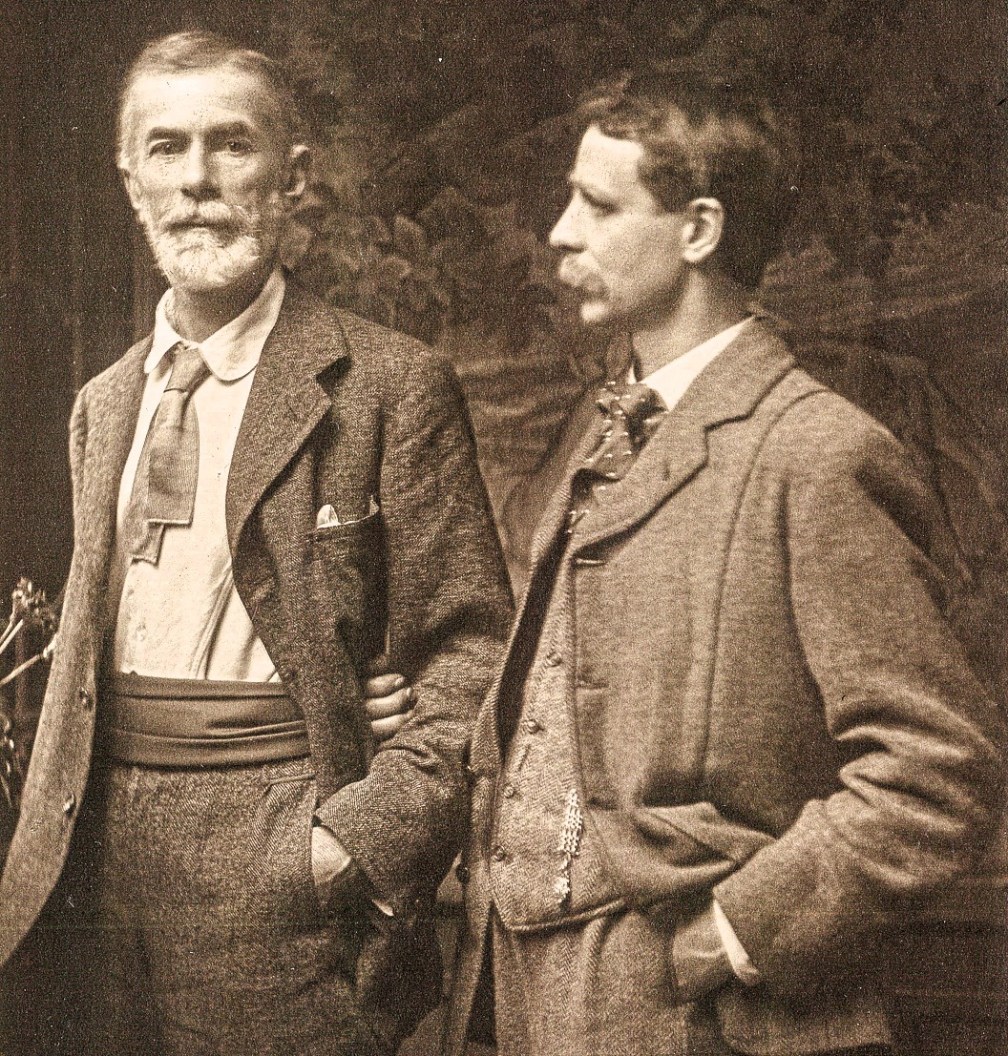

In a sunny Yorkshire dale, some twenty miles beyond Sheffield, lives Edward Carpenter. His life is a quiet and sheltered one, spent for the most part in farming and out- door work, varied by trips to the great cities and occasional lecturing. His name has won as yet no universal fame. Even in England, the country of his birth, his literary message is only beginning to be understood; here in America his readers are few and far between. Yet Carpenter is one of the most striking figures in modern literature. He has shown himself to be a true interpreter of the most vital influence in the life of our times,–the movement toward industrial democracy, and with Walt Whitman he shares the distinction of creating a new poetic form as free and untrammeled as the ideal world of which he dreams.

Edward Carpenter, who came into the Socialist movement from an upper-class environment and a university training, has written some half-dozen prose works, and all of them are most valuable contributions to the literature of Democracy. He helped to start “Justice”, England’s first Socialist paper, and wrote for William Morris’s journal “The Commonweal”. He compiled and published “Chants of Labour”, a book of songs for radical meetings, in the early eighties, and followed this up with a characteristic selection from lectures and essays, printed under the title “England’s Ideal”. In 1889 appeared “Civilization, Its Cause and Cure”, a most interesting series of essays on social and scientific subjects; and in 1890, “From Adam’s Peak to Elephanta”, an account of travels in India. During recent years Carpenter has devoted a great deal of attention to sexual problems, and his book, “Love’s Coming of Age”, is as suggestive and notable a treatment of this subject, from the Socialist point of view, as has yet appeared in the English language. Carpenter’s last contribution to literature is a book of essays on art and music in their relation to social life, published under the name “Angels’ Wings”, and he is at present engaged in writing a book on comradeship and the famous friendships of history.

All Carpenter’s literary work bears the unmistakable impress of his genius and personality, but it is in the poetry of “Towards Democracy” that one gets closest to him. Here we touch the very soul of the man; here we get his message in words that are more intimate than the words of prose could ever be. For there is in Carpenter’s poetry the freedom of prose and the restraint of poetry, and many of the strongest qualities of both prose and poetry. A critical student of Carpenter’s poems has said:

“Towards Democracy” has all the indefiniteness of life. In form and nature it approaches life: its object is life, its subject is life, its sole predicate is life, and if for many its rhythm is chaotic and its meaning confused, the complexity of life is alone responsible. To conceive the nature of the rhythm of ‘Towards Democracy’ and once to conceive is ever afterwards to realize–it is necessary only to compare a few passages with even the best and purest prose. There is about the one a movement, a recurrence of accent, a satisfaction of the inner ear, a sense of completeness and sweetness which prose lacks. The words are less ordinary, the syntax is often that which prose would disapprove; the repeated phrases, like a sweet refrain, gently insistent and accomplishing counterpoint, are inexcusable in all but rhetorical prose; the sequence of ideas is less logical than harmonious, for life is transcendent of logic; there is an onomatopeia of phrase and sentence which in prose would be affectation. The psalmic form of Carpenter and Whitman is the rhythm of self-expression: for in its ultimate analysis, since no fact is truly isolated and no rhythm but bears a relation to a greater, and both exist but as parts of the mind that conceives them, self-expression can be neither exclusively dramatic nor exclusively lyric, and but seldom regular in rhythm or rhyme.”

Edward Carpenter sings of all the basic emotions in human life, but into them all he reads the democratic passion. In religion he stands for a kind of pantheism, declaring that “on all sides God surrounds you, staring out upon you from the mountains and from the face of the rocks, and of men, and of animals.” At times he hints at a conception of immortality that includes reincarnation and the frequent “passing through the gates of birth and death.” But the distinctively religious note finds no emphatic expression in Carpenter’s philosophy. Like Morris, he would say that he has little interest in questions of metaphysics and theology, but a great love for the earth and all the life of it. Nature-love dominates him, and he is never tired of celebrating “the love of the land, the broad waters, the air, the undulating fields, the flow of cities and the people therein, their faces and the looks of them, no less than the rush of the tides and the slow hardy growth of the oak and the tender herbage of spring and stiff clay and storms and transparent air.” “I propound a new life for you,” he cries, “that you should bring the peace and grace of Nature into all your daily life—being freed from vain striving.” And again:

“Between a great people and the earth springs a passionate attachment, lifelong,—and the earth loves indeed her children, broad-breasted, broad-browed, and talks with them night and day, storm and sunshine, summer and winter alike…

“Government and laws and police then fall into their places–the earth gives her own laws; Democracy just begins to open her eyes and peep! and the rabble of unfaithful bishops, queens, patronisers and polite idlers goes scuttling down into general oblivion.

“Faithfulness emerges, self-reliance, self-help, passionate comradeship.”

With Carpenter’s nature-love goes a keen sense of the unity of the world and its unfolding life “I saw deep in the eyes of the animals the human soul look out upon me,” he says, “I saw where it was born deep down under feathers and fur, or condemned for a while to roam fourfooted among the brambles. I caught the clinging mute glance of the prisoner, and swore that I would be faithful.” With Carpenter’s universal sense goes, too, a realisation of the fitness of all things, “good” and “bad” alike. He identifies himself with the criminal and the outcast, looking back of them to the environment that has made them what they are, and recognising that their very crimes are a protest against social injustice and an unconscious augury of the true society. “You try to set yourself apart from the vulgar,” he declares in one passage; “it is in vain. In that instant vulgarity attaches itself to you.” “Your talk of goodness I despise,” he cries with startling frankness; “to every conceivable sin I hold out my hand.” Again, he declares: “There is nothing that is evil except because a man has not mastery over it; and there is no good thing that is not evil if it have mastery over a man;

“And there is no passion or power, or pleasure or pain, or created thing whatsoever, which is not ultimately for man and for his use–or which he need be afraid of, or ashamed at.”

The gentleness of Carpenter’s nature is no less marked than is the scorn and satire with which he lashes present- day society. Do you think your smooth-faced Respectability will save you?” he says; “do you think it is a fine thing to grind cheap goods out of the hard labor of ill-paid boys? and do you imagine that all your Commerce, Shows and Manufactures are anything at all compared with the bodies and souls of these?” “Back!” he exclaims; “make a space around me, you kid-gloved, rotten-breathed, paralytic world, with miserable antics mimicking the appearance of life!” In another passage he says, with dryest humor:

“World of pigmy men and women, dressed like monkeys, that go by,

“World of squalid wealth, of grinning galvanized society,

“World of dismal dinner-parties, footmen, intellectual talk,

“Heavy furnished rooms, gas, sofas, armchairs, girls that cannot walk,

“Books that are not read, food, music, novels, papers, flung aside,

“World of everything and nothing–nothing that will fill the void,

“World that starts from manual labor–as from that which worse than damns–

“Keeps reality at arm’s length, and is dying choked with shams,

“World, in Art and Church and Science, sick with infidelity, “O thou dull old bore, I prithee, what have I to do with thee?”

Carpenter’s conception of social progress is that of constant change, growth, development. The different stages of society, he says, are like the natural sheath which protects the young bud “fitting close, stranglingly close, till the young thing gains a little more power, and then falling dry, useless, its work finished, to the ground.

“Out of present cramped forms society is inevitably passing toward conditions of equality and ultimate communism He writes:

“I heard the long roar and surge of History, wave after wave–as of the never-ending surf along the immense coastline of West Africa.

“I heard the world-old cry of the down-trodden and outcast: I saw them advancing always to victory.

“I saw the red light from the guns of established order and precedent–the lines of defence and the bodies of the besiegers rolling in dust and blood–yet more and ever more behind!

“And high over the inmost citadel I saw magnificent, and beckoning ever to the besiegers, and the defenders ever inspiring, the cause of all that never-ending war—

“The form of Freedom stand.”

***

“O Freedom, beautiful beyond compare, thy kingdom is established!

“Thou with thy feet on earth, thy brow among the stars, for ages us thy children,

“I, thy child, singing daylong, nightlong, sing of joy in thee.”

Simplicity in food, dress and material things; intellectual and bodily strength; passionate comradeship and clean sex-relationship; sympathy and love for all life, human and animal alike; free living close to the woods and the fields and the open sea,–this is the Carpenter ideal.

May the day be hastened when it shall be realised for all the human race!

The Comrade began in 1901 with the launch of the Socialist Party, and was published monthly until 1905 in New York City and edited by John Spargo, Otto Wegener, and Algernon Lee amongst others. Along with Socialist politics, it featured radical art and literature. The Comrade was known for publishing Utopian Socialist literature and included a serialization of ‘News from Nowhere’ by William Morris along work from with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Nast, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Edward Markham, Jack London, Maxim Gorky, Clarence Darrow, Upton Sinclair, Eugene Debs, and Mother Jones. It would be absorbed into the International Socialist Review in 1905.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/comrade/v01n02-nov-1901-The-Comrade.pdf