Even in poorly organized workplaces at times of low class struggle, strikes can be transformative. A worker writes of the experience of 1800 strikers at Mansfield, Ohio’s Empire Steel plant in 1930.

‘Strike!—Mansfield Steel Workers’ by A Steel Worker from Labor Age. Vol. 20 No. 6. June, 1930.

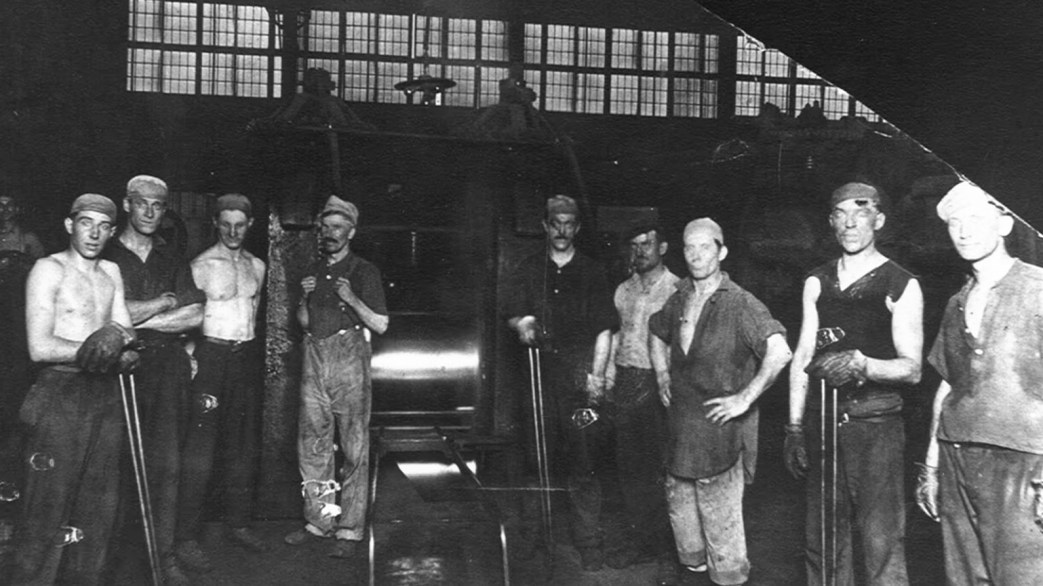

“Come on, let’s quit!” were the shouts which shook the walls of the old North plant of the Mansfield, O., works of the Empire Steel Corporation on May 12. Before nightfall all 1,800 men had pulled the steel from their furnaces, discarded their tools and were on strike.

No one seems to know how it started. There had been no meeting of the men nor were there any labor “agitators” about the town that anyone knew anything about. It all happened when some of the workers had gone out to the mill gate and spied a notice posted by the company declaring another Io per cent wage cut. These men rushed back into the plant and spread the latest news and the walk-out followed.

This was the second cut handed to all of the workers of this plant since the first of May and it was to be retroactive taking effect May 1st with the other 5 per cent announced then. In all, these workers had suffered the loss of something over 37 per cent of their wages since a year and a half.

It was rather significant that little or no protest was raised by the workers over a period of 18 months when the company had reduced their wages almost 25 per cent. But times were bad and there was some danger of losing their homes if a strike was called and the mill shut down. Most of the workers employed by the Empire Steel are white Americans, many of them having been with the company since 1915 when Bill Davy, an old roller himself, had first opened the Mansfield plant. From the very first Davy would have nothing to do with unions but he would take care of his men. And for a time he did. The war came along with its unlimited demand for steel sheets and the plant worked full blast day and night. Prices were high and wages reached an undreamed peak. When the crash came after the war it caught Davy in the midst of an expansion-and remodeling program. The storm was weathered with the aid of Cleveland capital. The workers were forced to fall back on their meager savings, that is those who had been able to save. Others had mortgaged their homes or borrowed when they could. The company loaned money to some of the more “worthy.” For years the company had helped its workers out of trouble. At first it made gifts outright in case of sickness, later the gifts were converted into loans. The Davys had tried to take care of their workers.

Things Different Now

But things are different now. The Mansfield plant is just one of six which were merged together in 1928 to form the Empire Steel Corporation and the 5th largest sheet steel company in the country. The ambitious Bill Davy catching the spirit of the times bought up three plants in Niles, O., one in Ashtabula and Cleveland and combined the original Mansfield plant to form the Corporation with assets totaling over $23,000,000. But things did not go so well with the new Empire Corporation. Bill was too generous. He had placed five of his brothers in high executive positions with exorbitant salaries. The smaller stockholders raised a voice of protest, other executives were jealous and the workers were becoming restive. So last year Pickand, Mather and Company, a huge Cleveland ore concern, purchased Bill Davy’s controlling interest. Now the Davys are no longer a part of the Empire Steel. Although the president of the company, Carl Hinkel, is a local Mansfield man, the Cleveland capitalists control the corporation. This same company, Pickand, Mather and Co., figured greatly in the recent merger trial in Youngstown which was waged between the Youngstown, Sheet and Tube and Bethlehem Steel interests and the Eaton capitalists of Cleveland. Pickand, Mather took sides with S. and T and Bethlehem in favor of the merger. It was brought out in the trial that Pickand, Mather had purchased something over $9,000,000 worth of Sheet and Tube stock for Bethlehem. And Bethlehem is one of Pickand, Mather’s best ore customers.

These two companies own several ore companies jointly.

Things are different now. When the workers walked-out May 12 they challenged not the Davy family but a combination of capitalists with unknown resources. But the workers did not stop to think about all of this until after they had closed the plant tightly. They had stood for the first 25 per cent reductions but the last 15 per cent was, “the last straw,” the straw which broke the camel’s back. “We would rather die fighting, than starve working,” was the way they put it the first evening of the strike at a huge mass meeting.

The Mansfield workers knew little about strikes or how they were run. They called in officers of the Local Trades Council for assistance. Committees were formed and demands drawn up to be submitted to the company. Some old time members of the A.F. of L., Amalgamated Association of Iron Steel and Tin Workers Union, got in touch with the Pittsburgh officials asking for assistance. The Communist Metal Workers Industrial League sent in representatives. Officials of the company were sitting tight waiting to hear the demands of their workers. Pickets were placed at the plant gates, although unnecessary, for no one cared to go back to work until the strike was settled. There was no sign of violence anywhere.

All through the second day of the strike the steel worker held department meetings to discuss the demands which were to be submitted to the company. The grievances had long expanded. The return of the last 15 per cent wage reduction became only one of many demands. The workers wanted an 8-hour day for the hot mills and the elimination of Sunday work. In the past they had received no pay for “cut-downs” and “seconds”; they wanted pay for these. The laborers were asking for 40 cents an hour instead of the 32 cents they were receiving. Many other items concerning the conditions of work were being talked over. All of these were agreed to and incorporated in the “terms” under which they were willing to return to work.

Union?

But there was one fundamental issue over which there waged much controversy. Were the strikers to demand the right to have a union? During the first couple days opinion was all but unanimous for a union. They reasoned that unless they had a union they would have no protection in the future. To be sure the men had walked-out, but the next time it would not be so easy without some form of organization. Officers of the Amalgamated Association were in their midst ready to take them into the fold. A huge mass meeting was held and over 1000 men voted to sign the A.A. pledge. A few did sign but the supply of pledge cards became exhausted and they were told to come around to the union hall on the following day when there would be more cards available. Then, too, a five dollar initiation fee must be given.

But over night something happened. Union officials were on hand with pledge cards, but the men were not signing. Committee meetings were held, and after long debate it was decided to have nothing to do with the A.A. for the time being. The strikers were in favor of asking for the right to organize locally. It was rumored about that the company was in financial straits due to the fact that something like $800,000 worth of bonds had matured and the banks had refused to renew them. Strike leaders feared that to hold out for recognition of the International Union would mean defeat since they were quite certain that the company would not consent to pay the union scale of wages which was 30 to 35 per cent higher than their rates. Then, too, the citizens of Mansfield who had been shocked when the strike became known, were circulating the opinion that to prolong the strike would mean the breaking of the company and the ultimate stoppage of all production by the Empire Steel Corporation in Mansfield. This, they believed, would ruin the town since the Empire pay roll amounted to nearly $200,000 each month. So the A.A. officials were asked to quietly withdraw.

Strike Is Won!

After four days the peaceful strike came to an end. The company rescinded the last two wage cuts and restored the April 30 scale. The workers compromised and accepted a 36 cent rate for the laborers. All other demands were held in abeyance until a committee composed of workers and representatives of the employers could get together to talk them over.

The Mansfield steel workers had won against the company’s wage cuts. They have the promise of a grievance committee which will discuss other grievances. It remains a question, now that the men are back on their jobs, just how effective the workers can be without a union.

No matter what happens in the future it still remains a fact that the complacent Mansfield steel workers struck and defeated the Empire Steel Corporation’s wage cutting program. These workers have set a precedent for all other wage earners in the steel industry throughout Ohio and the country at large. All of the larger steel corporations have initiated brutal wage cutting campaigns and it is a good guess that the Mansfield strike will give them something to warrant more caution in the future. Already other workers in other plants are beginning to ask themselves why they cannot do what the Mansfield workers have done.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v19n06-Jun-1930-Labor-Age.pdf