The epic story of the 1910 Chicago garment workers’ strike, ‘The Strike of the 50,000,’ with top-drawer labor journalism from Robert Dvorak, a companion to an earlier article, continues. One of the most important strikes of its time, the 1910 Chicago garment workers strike went down to defeat, but began a wave of strikes and organizing in the industry. Robert Dvorak was the lead reporter on the strike for the Chicago Daily Socialist…until he began reporting on the rank and file’s rejection of the union leadership’s offers for which he was fired.

‘Fighting Garment Workers of Chicago’ by Robert Dvorak from International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 7. January, 1911.

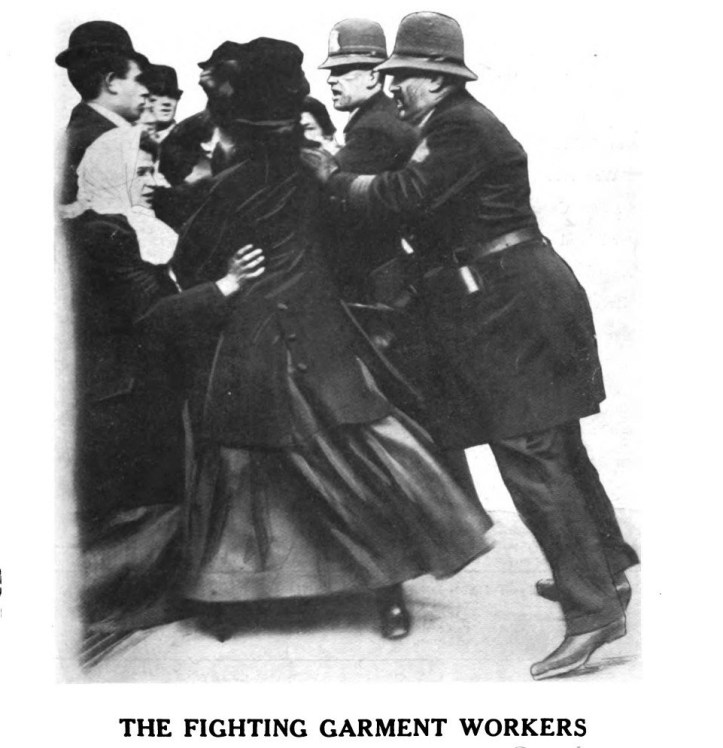

MAULED by city police, assaulted and beaten by armed, hired sluggers, shot by strike breakers and now being faced with a winter full of the horrors of cold and starvation, the striking garment workers of Chicago still remain undaunted.

Not even the best efforts of the mayor, the city council, the Chicago Federation of Labor and very influential persons, such as Raymond Robins and other “Good Samaritans” can force the “ignorant strikers” to accept meaningless but well worded terms of peace from the hard pressed renegades, Hart, Schaffner and Marx.

For the first time in history the autocratic Chicago Federation of Labor, headed by John Fitzpatrick, ably assisted by Mrs. Raymond Robins, has been nonplused. Over 41,000 garment workers have refused to obey the pleasure and whims of the leaders and have refused to go back to work upon the order of a president who tried to hand them lemons labeled as agreements and victories.

When the strike began on September 30th the Chicago Federation of Labor looked upon it as a joke. No one looked upon it seriously except the strikers themselves and a few of the garment workers’ leaders who were more intimately acquainted with the situation. There was a strike in existence, but few knew about it. The capitalist papers refused to write, and the Chicago Federation refused to act. A strike was on but no one knew its extent.

Then it was that the Chicago Daily Socialist, urged and entreated by the strikers, took action, and on October 7 published its first story of the strike and what brought it on. A week later the other daily papers took action, but not until after thousands of copies of the Daily Socialist had been distributed free of charge by the strikers in the city.

Before six weeks had passed by, a general strike of all the garment workers in the city, outside of those employed by union concerns, had been called. From an unorganized strike, composed of unorganized workers, sprang an organized movement for a recognition of the union, and the manufacturers, themselves harassed by internal fights over profits and business supremacy, grew uneasy.

Workingmen and women all over the United States, attracted by the brave and determined fight of the garment workers against the greatest odds, began to act. They refused to buy clothing without a label and warned local business men against buying clothing from the strike bound Chicago concerns, and the uneasiness of the manufacturers grew from day to day.

After the calling of the general strike there began in Chicago the greatest and most unique strike ever known in the history of labor struggles. Started by sixteen girls, without the vestige of organization, the struggle spread to 41,000 persons and tied up almost 200 shops.

Labor papers all over the country took up the astounding fight and unions began to send in cash donations. Farmers, the best customers listed on the books of the strike bound concerns, sent in letters and resolutions condemning the manufacturers and an entire fall and winter clothing trade was crippled or ruined.

Doctors agreed to treat patients free of charge. Barbers gave free shaves, theaters gave benefit performances. Private families housed and fed homeless strikers. Druggists gave free drugs or offered a certain percentage of their daily profits. Grocers and butchers gave free food supplies to the various free supply and relief stations. Clubs and societies gave benefit balls and entertainments. Song writers and artists offered their productions and gave the strikers the full profits and the hotel keepers refused to house the strike breakers.

Business and professional men, of whom the majority were members of the Socialist party, organized a strikers’ aid committee and in two weeks’ time collected over $3,000.

The strike was progressing admirably. Public sentiment was with the garment workers in every part of the country and money was just beginning to come in, when President T. A. Rickert, head of the national organization of the United Garment Workers, brought the strikers a peace offer from the Hart, Schaffner and Marx concern.

Rickert had signed the peace offer and tried to railroad it through the ranks. The offer guaranteed the workers nothing more than an assurance that every striker would be taken back irrespective of whether he belonged to a union or not, and a promise that many of the abominable persecutions would be abolished.

Hisses and angry cries greeted Rickert and his peace offer when he read it before the cutters at Federation hall, 275 La Salle street, Saturday afternoon, November 5. The same fate met the fatal agreement when it was presented to the strikers at Hod Carriers’ Hall, and at all the other meetings.

Dazed and dejected, Rickert abandoned all idea of settlement on the terms offered by Hart, Schaffner and Marx, and instructed his organizers to work as they had never worked before organizing and aiding the determined garment workers. For the first time in his life Rickert met determined workers who ignored the wishes and advice of their superiors and he submitted gracefully.

Later in the week, following his Waterloo, Rickert gave his one reason for endorsing the agreement. He stated that the demands for strike benefits had been so great and the income so small that he feared the possible suffering that was likely to follow inability to pay the men, women and girls. The starvation bogy had made its first appearance and was brushed away by the only people it could affect.

Their faith in Rickert and many of the other garment union officials shaken, the strikers with the aid of the Daily Socialist, of which over 10,000 extra copies had been sold one Sunday afternoon, following the rejection of the peace offer, appealed to the Chicago Federation of Labor for aid.

This time the federation, at its meeting, endorsed the strike of the garment workers and assessed its members 25 cents each. John Fitzpatrick, president of the Chicago Federation, and Mrs. Raymond Robins, president of the Women‘s Trade Union league, took the strike in hand and began work by appointing working committees composed of women prominent in Chicago.

Four food supply stations were established in various parts of the city and the strikers asking for help were given cards good for the amount food punched in therein. The supply stations lessened the demand for actual cash and the strike once more was progressing in a most satisfactory manner. The most admirable and contagious strike meetings were held in thirty-seven various halls in the city and money was pouring in from all parts of the country, with letters of encouragement and promise of further aid when another blow, again from union headquarters, once more nearly demoralized the strikers.

Alderman Charles E. Merriam, pressed by some outside influential persons, brought the strike question up at the council meeting Monday, Nov. 28, and asked that a committee be appointed by the city body for the purpose of trying to end the strike. Mayor Fred Busse, City Clerk Francis D. Connery, and Aldermen Chas. E. Merriam, William F. Ryan and Winfield P. Dunn were elected on the committee.

The Chicago Federation of Labor was represented by John Fitzpatrick, at the subsequent meetings. the garment strikers by Edward Anderson, the garment workers’ union by Samuel Landers. national organizer, and the Women’s Trade Union League by Mrs. Raymond Robins. Hart, Schaffner and Marx stock holders were represented by Levy Mayer and Harry Hart.

Four locked door meetings were held in the mayor’s office and not a soul outside of the main strike committee knew what was going on. Then the silence was broken and another peace offer was flaunted before the eyes of the workers.

Great wordy speeches accompanied the reading of the agreement by the union officials, but no amount of flowery talk and beautiful visions of organization at a later day could cover the fact that the new peace offer was only a repetition with but one exception of the brand submitted by Rickert, more than a month previous, and another storm of dissent greeted Fitzpatrick and his assistants when they read it at the meetings.

Not even the fact that the agreement had been recommended for acceptance by the Chicago Federation of Labor delegates could alter the strikers’ feeling, and Fitzpatrick, like Rickert, discovered that he was dealing with unorganized but well posted workers, who knew what they wanted and refused to be told what to do and when to do it.

The Fitzpatrick agreement again guaranteed the strikers a position within fifteen days without regard to whether they were strikers or not, and specified that an arbitration committee of five members, two of the union, two of the manufacturers and one to be chosen by the four, was to be appointed to settle all grievances. It further stated that no discrimination was to be practiced against either the union or non-union employes.

Seeing that no amount of cajoling, entreating or intimidation could get the strikers back to work, and fearing to submit the agreement point blank in person, Fitzpatrick and the strike board decided to take a secret ballot vote after the bitterness had died down somewhat.

Mrs. Robins and the Women’s Trade Union League adopted a new policy, however, and began the work by giving out horror-inspiring interviews to capitalist press reporters on the terrible suffering and extreme starvation among the strikers.

Columns of interviews bearing directly on suffering of the strikers were given out by Mrs. Robins, and the capitalist papers featured these with extra coloring and display. A picture taken early in the strike showing a group of Jewish and Italian strikers was printed and declared to be that of families evicted by landlords for non-payment of rent, said to be living in one room.

The strikers condemned the stories, and votes taken in the various halls failed to show one person who had suffered from starvation or even the slightest lack of food.

Mayor Busse and his aldermanic committee tried their best to secure a similar agreement to that signed by Hart, Schaffner and Marx from the Wholesale and National Clothiers’ Association, but these worthy gentlemen laughed and told him that Hart, Schaffner and Marx brought the strike on and could fight it out itself. They refused to arbitrate through their representative, Martin I. Isaacs, and the city hall attempt to aid the great strike was a fizzle of the worst kind.

Following the sentiment expressed by the strikers for rejecting the last agreement of the Hart, Schaffner and Marx concerns, the Socialist party stepped in and determined to aid financially so determined a band of workers.

At its meeting, Sunday, December 11, the national executive committee of the Socialist party passed a motion instructing the secretary to insert an emphatic appeal in the coming issue of the National Bulletin, calling upon all Socialists to aid to their utmost the striking garment workers.

The Cook county central and delegate committee, at a meeting on the same date, instructed the secretary to issue subscription lists and to do his utmost to secure funds for the strikers. The delegates further instructed the editor of the Daily Socialist to insert a permanent appeal for funds in the columns of the paper.

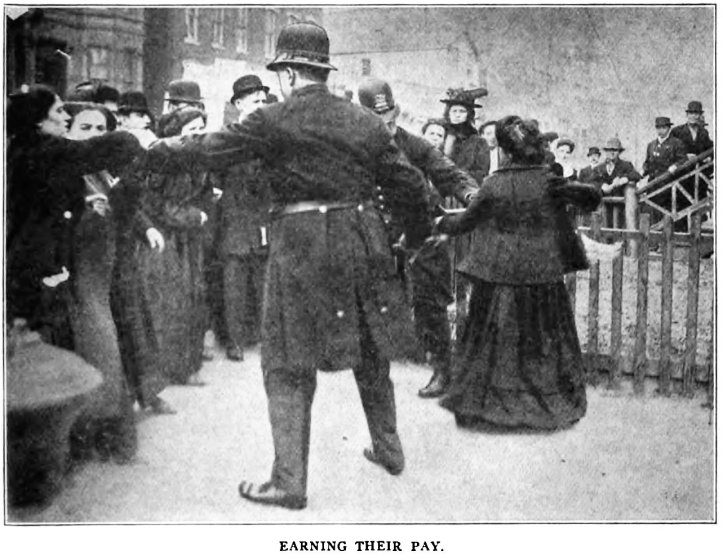

While the negotiations for peace were going on, the strikers were suffering from the razors, knives, clubs and revolvers of the hired sluggers, special detectives and armed strike breakers who were furnished with weapons by the strike-bound concerns. No person daring so much as brush up against a strike breaker was sure of his life, for the beasts in human skin had an ever-handy revolver or other weapon ready to kill or maim.

The first weeks of the strike, the sluggers and “detectives” used only clubs with which they broke the heads of more than a score of strikers. Later they gained courage and displayed revolvers and steel knuckles. Not being interfered with by the police, they began to fire the revolvers and use the knuckles openly. Finally they began to take aim and a number of strikers, women and men, fell to the ground shot with bullets furnished by their employers.

Finding the hiring of special detectives and sluggers a little too expensive the owners of sweatshops armed their scabs with firearms and a girl striker lost a finger as a result of this new and money-saving move.

She and a few of her companions had gathered near the home of a girl scab and tried by persuasion to bring her to their ranks. An automobile drove up while they were arguing with her. She jumped into it. A brother of the girl scab lifted a rifle to his shoulder, a shot echoed and Miss…had one finger less.

Every day strikers reported to headquarters with tales of how they had been shot at and attacked by armed strike breakers. Protests galore were made to Leroy T. Steward, chief of police, but he only shook his head sagely and said: “Wait until the strike is over.”

Then all at once, while the peace conference in Mayor Busse’s office was going on, Charles Lazinskas, a striking garment worker, was attacked while speaking to several scab girls in front of the Royal Tailors’ establishment, and shot through the heart by Martin Yacullo, a tailor, who had been made a special detective by the strike-bound company.

The murder acted like a spark in a pan of gunpowder. Not one striker had committed any violence up to this point. Some had broken windows, true enough, but no person had been seriously, or other wise, hurt by the strikers. The murder of their comrade, however, fanned the strikers into a fury and several detectives were beaten so badly the following day that they had to be taken to a hospital.

Even the police were stirred into activity and an order was issued to the policemen to arrest any person caught carrying concealed weapons of any kind. At an inquest held over the dead body of Lazinskas the coroner’s jury held the murderer, Yacullo, to the grand jury.

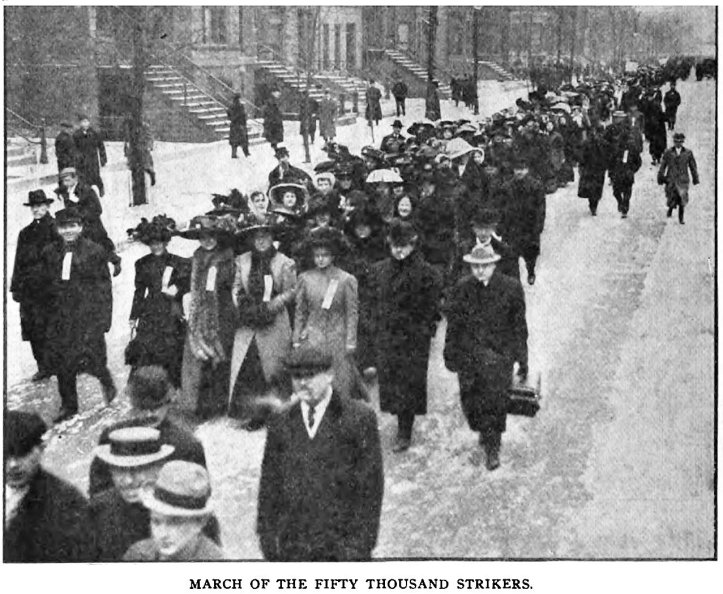

There never was a funeral in Chicago such as was held in the case of the murdered garment striker. Thousands of men, women and girls followed the hearse that carried the body of their comrade.

They marched with their heads bowed. On their coat lapels and breasts each striker had a piece of crepe pinned down with the union button of the garment workers. Banners carried by the thousands proclaimed to other workers that another person had fallen victim to the greed of the employers.

Every person who took part in the funeral march swore solemnly that he or she would never go back to work until the bosses gave them what they wanted or at least a big part of it. They condemned the pending agreement in the most bitter terms, but the Chicago Federation of Labor would not be warned, and various attempts were made to force the agreement upon the strikers at various meetings. Speakers were sent out to talk the people into the peace offer, but these were hissed and hooted out of the halls.

At Hod Carriers’ hall, where the largest part of the strikers meet every day, John Fitzpatrick and Mrs. Raymond Robins tried to tell the people to go back to work, and read the peace offer. There was a storm of protest and neither one of the union officials could be heard. One Jewish worker got up on a chair while the storm was on and holding up his hands said:

“Brothers and sisters, we have just put our murdered comrade into a grave. He was fighting with us against the murderers who own the big tailor shops. He was killed by a man who was given a gun and bullets by the bosses. Now they want us to go back to work and offer us nothing.

“Just think, my brothers and sisters, of how we have been clubbed, shot at, robbed and murdered. It was all because we wanted better conditions. Now they bring us an agreement that is nothing and tell us to go back. I say no, brothers, I say no—and I know that poor Lazinskas in his grave would say no too.”

There was a storm of applause that could not be quieted when the speaker finished and the crowd began to surge threateningly against the platform where only a little over a month before Robert Noren had almost received a beating at the hands of the strikers when the Rickert agreement was proposed.

The funeral of Lazinskas was held on Monday, December 5, and was viewed by thousands of people. The Wednesday following 50,000 strikers left their homes early in the morning, and braving the cutting wind, marched for two hours through the streets of Chicago in a protest against police brutality, murderous sluggers and the conditions in the tailor shops.

Following the parade, the police brutality stopped to a large extent and several strike breakers caught with concealed weapons were arrested for the first time since the beginning of the strike. Public sentiment at last won a slight victory.

As a sample of the police tactics used against the strikers and their extreme brutality it is only necessary to cite the case of Frank Kriz, living at Trumbull avenue and Twenty-fifth street:

Kriz was on his way to the home of a friend when he saw a great crowd of people on the corner of Homan avenue and Twenty-fourth street. He stopped to watch the sight of strikers being beaten by police while picketing the shop of a tailor known as Peklo, when a policeman, Sergeant Scully of the Lawndale street police station, dashed up and lifted his club.

Seeing that a broken head would be the only result of standing still, Kriz ran into a private home near where he was standing. Scully pursued him. They ran into a kitchen. From there into a parlor and finally into a bedroom. Here Scully caught Kriz and beat him mercilessly. Then pulled him out and arrested him. Kriz had his wrist almost broken, his ears were swollen, two bumps pained him on his head, and a welt rose on his neck.

Finishing with Kriz, Scully dashed into the corner saloon of Frank Merhaut and began to pull people away from the bar. Merhaut protested and was told to shut up or get a crack over the head. After cleaning out the saloon Scully, who had been drinking extensively in the scab shop of Peklo, grinned like a hyena and returned to the street, where he scored policemen who were not busy enough breaking the heads of working men.

The fiendish work of Scully has been repeated throughout the city time and time again, since the strike began, and it is such work as that which has won the strikers the sympathy of the public and has brought condemnation upon the police and the strike-bound firms.

In another case a number of policemen guarding the strike-bound shop of the Royal Tailors, saw a strike-breaker pull out a razor and slash with it at a strike picket who was standing on the corner. The police made no effort to interfere until after the poor fellow had been cut up so bad that it took sixteen stitches in the hospital to sew up his wound. The assailant escaped.

The most peculiar phase of the strike thus far has been the orderliness of the strikers. It has been a surprise to almost every one, even the police, that no outrages have been committed by the 40,000 persons of at least nine languages.

It would not surprise any one, though, if he attended the meetings of the strikers in their various halls and heard the instructions given them in various languages to remain peaceable, and in case of fight only use the two arms given them for defense. The strikers have followed these instructions in spite of the fact that it has cost them many a broken head where a fight with equal weapons might have resulted disastrously for the assailants.

There are four main nationalities involved in the garment workers’ strike, the Polish, Bohemian, Jewish and Italian. The Jewish workers are in the majority, as there are approximately 10,000 of them involved in the struggle. The Bohemians follow with about 6,000 strikers, the Polish with about 5,000, and the Italians with probably 3,500. The balance of the 40,000 strikers includes Slavs, Hungarians, Lithuanians, Germans and Bulgarians.

Very few people understand the present strike and the workers involved in it because of their peculiar tactics. They are a band of people trained to look with suspicion upon the actions of those placed in the position of leaders. They have faith only in themselves, and claim that as long as they stand together as workers, no power on earth can defeat them. They want a union of workers and not leaders.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v11n07-jan-1911-ISR-gog-Corn-OCR.pdf