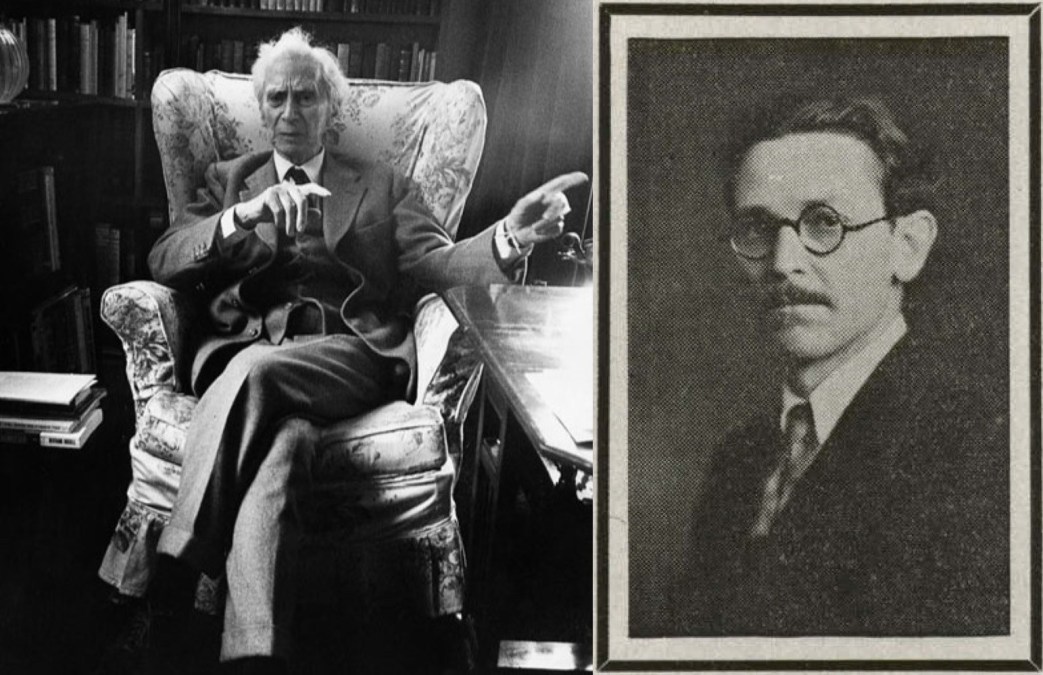

Kantorovitch with a critique of the ‘metaphysical materialism’ of Bertrand Russell.

‘Historical Materialism and the New Science’ by Haim Kantorovitch from Modern Quarterly. Vol. 5 No. 1. November, 1928-February, 1929.

R. BERTRAND RUSSELL is well known for his humanitarianism. He was as willing to give up his freedom in his humanitarian fight against war as he has been to risk his reputation as a philosopher in his not less humanitarian attempt to popularize knowledge for the masses. Seeing that “there is in our time a widening gulf between the scientific specialist and the ordinary intelligent man” he has decided to give up his calling as an original philosopher and mathematician, to devote his entire time to popularizing the new sciences for the general reader. Whether he is very successful as a popularizer is still an unsettled question, but that he is very efficient and productive in his new task, there can be no doubt. We often are simply stunned by the rapidity with which he writes and publishes his popular books.

Lately he has undertaken the difficult task of teaching the new physics to the readers of the Saturday Review of Literature (issue of May 26, 1928). He could not, of course, content himself by simply stating wherein and in what ways the new physics differs from the old physics. He has taken upon himself a much greater task: to show how the new physics revolutionizes all our beliefs; what beliefs we must, in accordance with this newer science, abandon, and what beliefs we must put in their place.

“I think,” says Mr. Russell, “that if we were to search for one short phrase to characterize the difference between the newer physics and that of past times, I should choose the following: The world is not composed of “things.” Startling, is it not? Just imagine a world composed not of “things!” By things we are, of course, to understand material things, for, after all, even according to Mr. Russell, there are “things” in the world, only they really are “apparitions, changing gradually as time goes on.” That is, there are in the world “things” that are “not things” that appear to us as “things.” In his former works Mr. Russell used to call these “things” relations, sense data; now, in obedience to the dictates of the newer physics he has changed their names to “inferences” or “events.” In order to make his thought more popular he illustrates it thus: when you watch a game of billiards you think that one ball hits another and pushes the ‘other away. This, however, is an illusion. The balls never touch; the outer electrons in the one repel the outer electrons in the other; these outer electrons try to move inward, but are in turn repelled by those that they are thus compelled to approach. That is, of course, very instructive, and certainly very interesting for those who did not know it, but as yet, there is nothing astonishing about it. The most important and most amazing thing (apparition) is what follows. Why do the balls move after all? Because, “there gets to be an unpleasant sense (i.e., in the balls) of overcrowding. There is nothing for the whole lot to do except to move away, and look for a place where they do not have such unpleasant neighbors.” “And further,” it is not that the electrons are actually in contact during the jostle; it is merely that they dislike the too close proximity of other electrons.” Just imagine the wonders of the newer physics! The balls that are really no balls at all, but only electrons that are not really electrons but only “forms of radiant energy, or, as Schrodinger’s vanes,” have an unpleasant sense, they move away, they look for other places, they dislike certain things; in short, they are really smart electrons, knowing well what is good for them, looking for better places, and avoiding bad neighbors. If they have an unpleasant sense, they must at least be able to sometimes have also a pleasant sense. We must then go a step further and imagine that those electrons are able to feel and to distinguish between the pleasant and unpleasant. If they have no consciousness, they must at least possess some kind of faculty of awareness; maybe they have a soul, too, maybe even an immortal soul. Who knows what the newer physics will yet discover?

And yet, to one who is acquainted with the history of philosophy, and especially with its metaphysical branch, there is nothing in what Mr. Russell says. It has been proclaimed by metaphysicians since Plato, and registered in the history of Philosophy under the names of idealism, animism, or antropomorphism.

That the world does not consist of “things” or at least, that we know nothing about the things as they really are, that we deal in apparitions, is as old as philosophy itself. Mr. Russell himself admits it. “To the metaphysician,” he says, “this is no new plea.” The only difference between the old Metaphysics and the new is, according to Mr. Russell, that “in the past the metaphysician could not point to the technique of science, as being on his side.” Now it is different; metaphysics can now call science to its aid, “we are such stuff as dreams are made of” was once a piece of poetic imagination; now it is among the presuppositions of physics.”

How sweet it must sound to the metaphysician! But it is not the entire truth. The truth is that the idealist metaphysician was always convinced that science was on his side, while the materialist was always convinced that between idealism and science there is and always would be an impassable precipice. Both the idealist and materialist are still alive, and both are still convinced, each that science is on his side. It is, after all, a matter of interpretations, and it certainly would not harm Mr. Russell to remember the advice he gave his readers in his book of Sceptical Essays, “that it is undesirable to believe a proposition when there is no ground whatever for supposing it true.”

But Mr. Russell has a more important function than simply to popularize the newer physics. What he really intends to do is to drive home the philosophical consequences of these new discoveries: these consequences are summarized in this—”that is, of course, the death blow to materialism.” So at last we have it. Materialism, the philosophy that has been so often, and so many times, killed, is killed again by Mr. Russell, with the help of the newer physics.

What exactly is it that made Mr. Russell pronounce the death sentence on materialism? The fact that ‘‘the essence of materialism has always been the belief that the world consisted of billiard balls, or to take another illustration, that of the beam of light sent out by a lighthouse on a dark night. To the materialist it is evident “that the lighthouse is real and solid and tangible.” In other words, the fault of the materialist is that he sees “things” as real, and affirms the reality of matter. Billiard balls to him are billiard balls and lighthouses are lighthouses. This is very unscientific, because nobody really knows what matter is, and what is more, there is a grave doubt whether there is such a thing as matter at all.

If materialism should really affirm that it knows what matter is or that “the sole reality is matter,” as Mr. Russell says elsewhere (in his introduction to Lange’s History of Materialism), or that the essence of materialism should be as some believe, the belief that the object is identical with our sensation of it, as Lange says, Mr. Russell’s criticism would not only be true and justifiable, it would really be superfluous, because that kind of materialism, naive or common sense materialism, really belongs to a historic past. It is a stage of philosophy now buried. But is this materialism? This we deny.

F.A. Lange has written a history of materialism; Mr. Russell commends that history strongly. He thinks it is an important and useful book. We agree with him in this, but if there is a history of materialism, there must have been different schools of materialism. Which one does the newer physics kill? Is it the atomic materialism of Democritus, or the theological materialism of the Middle Ages, or the anthropological materialism of Feuerbach, or the metaphysical materialism of the French philosophers of the 18th century, or the dialectic materialism of Marx and Engels? These various schools differed among themselves in no lesser degree than they all differed from idealism.

The opponents of materialism, however, seem always to have in mind only one kind of materialism: the metaphysical and dogmatic—the one that professed to solve all the riddles of the universe by reference to the properties of matter, and reduce everything to the “movement of one atom.” It is no accident, for instance, that Professor Walter T. Marvin informs his students of philosophy that “for literature on materialistic side, the student is referred to Ludwig Buchner, Kraft und stoff: also to David Straus, Der alte und der neue Glaube.” So also does Prof. Paulson in his Introduction to Philosophy: and so do many others. Whenever an anti-materialist wants to show his audience a real materialist, he exhibits Buchner, Moleshot, Fogt, et al. The reason for it is evident, it is just as easy to refute Buchner as it is hard to refute Engels or Plekhanov.

Materialism to most who do not really know, or do not want to know what it is, is usually identified with the common sense view that billiard balls are billiard balls and lighthouses are lighthouses. It is taken as the philosophy of the unphilosophical; as the philosophy of the “man in the street” who, unable to see farther than his nose, takes things as they are, and firmly believes in their reality. Professor Marvin teaches his students truth about materialism thus.1 “The earliest ontological theories are materialistic, and we must conclude that materialism is naturally the first answer of man to the ontological problem”; primitive man, as we see, was a natural materialist, because “the primitive way of looking at things is an incipient materialism.” (Introduction to Systematic Philosophy, p. 185.) How much truth is there in this statement? No truth whatsoever. “Materialism is as old as philosophy, but not older,” declares F.A. Lange in his history of materialism, attacking this contention that materialism is unphilosophic, a relic of the primitive, common sense, naive, view of the world. That primitive man was the opposite of the materialist, one can discover from any book on anthropology. “It would seem,” says Professor McDougal in his Body and Mind, “that from a very remote period men of almost all races have entertained the belief that the living man differs from the corpse in that his body contains some more subtle thing as a principle which determines its purposive movements, its growth and self repair and to which is due his capacity for sensation, thought and feeling, for the belief in some such animating principle or soul is held by almost every existing race of man, no matter how lowly their grade of culture nor how limited their mental powers, and we find evidences of a similar belief among the earliest human records.”2

If McDougal is right, and there can be no doubt about it, primitive man was very far from being the natural materialist that the idealist professors have tried to make out of him. On the contrary, if philosophic terminology is to be applied to the mentality of primitive man, he was really an idealist. Professor Edward Taylor was certainly right when he saw philosophic materialism as the refined, and greatly developed, and civilized continuation of primitive animism. There is nothing new in this; after Engels and Plekhanov, it is an established truth.

“What is animism?” asks G.V. Plekhanov, and answers, “it is the effort of the savage (primitive man) to explain to himself the phenomena of nature, no matter how weak, how helpless this effort is; it is unavoidable under the conditions in which primitive man finds himself.”

Animism establishes the belief in spirits, souls, invisible powers as causes and as rulers—”on the sail of this animism religion arises, though its further development is determined by the evolution of society.”

But, not only religion grew on this animistic soil. It was a soil fertile also for the idealist philosophy—”once the belief in the creation of the world by some spirit was established, the soil was prepared for all those philosophic systems in which spirit (subject) is the underlying principle that determines, in one way or another, nature (object); this justifies us in taking all spiritualist, and idealistic philosophy—as opposed to materialistic—as a continuation of primitive animism”3

Idealism, arising out of animism together with religion, has taken among the more cultured the place of religion. Due to special social causes, religion has become one of the strongest pillars of the status quo of every society. Where religion as such with the superstitions that have grown up around it, could not serve its social purpose, idealistic philosophy has been evoked. “Philosophy,” says John Dewey, “was…invented in a fanciful way, in order to justify and preserve the existing social fabric…The sanction of traditional authority was its motive,”4 and so it has remained until and including today, we may add.

What is really the fundamental difference between materialism and idealism? It is the difference between common sense and philosophy, the anti-materialist professors imagine. “Almost all men of today are vaguely materialists,” says Professor Marvin, meaning to say that the everyday man, the Babbitt of today, is naturally a materialist. This is also Mr. Bertrand Russell’s belief, but is no more true than the assertion that primitive man is a natural materialist. The truth is that Babbitt is in mortal dread of materialism; he knows (his preacher told him, and he has read it in his newspaper) that the materialist wants to rob him of his immortal soul, and makes fun of the Christian virtues, of which he is so proud.

Babbitt could not conceive a world without a supreme power, without a “boss”—”If you can’t elect a president without a political boss, how could you imagine a universe without one?” such is the logic of a Babbitt. Living in a class society, where only “socialists and damned foreign agitators” dare imagine a society without bosses, foremen, rulers, and supreme powers, Babbitt can not be anything but an idealist; he must have a God, and if he is already “cultured” he will have at least an absolute idea, a spiritual substance, or something like it; of materialism he is afraid; it “smacks” of socialism. To be a materialist means to quarrel with the church (and with all respectable people). It means to become a rebel.

Now we have said it! That was the misfortune of materialism; under its banner rebels gathered. It was inscribed on the banner of nearly every revolutionary class, it served the “ancient lowly” as well as the rising revolutionary bourgeoisie, just as it now serves the revolutionary working class. That was its misfortune; that caused the mighty and powerful, the rulers of the earth and of people’s minds, to look at it not as upon a philosophy to which one is opposed, but as at an enemy that must be exterminated at all costs and by all means. Idealism has been combatted by philosophers, with purely philosophic weapons, but materialism has had the distribution of being combatted by philosophers, together with the church, the state, the school and the newspapers. Idealism may have been declared in error, but materialism was always an enemy, and an enemy must be destroyed even if he is correct: One was always reared and educated to be an anti-materialist.

That the fight of the ruling classes against materialism was successful, the whole history of philosophy can testify. Even people who really were, and are materialists, (Spinoza, Descartes, the agnostics, and even Mr. Bertrand Russell) were and are still willing to distort their own philosophies rather than take upon themselves the stigma of materialism.

But aside from its “social misfortune,” what is this materialism?5

The essence of materialism could be “…it abandons the claim to a special philosophic method or a peculiar brand of knowledge to be obtained by its means. It regards philosophy as essentially one with science, differing from the special sciences merely by the generality of its problems, and by the fact that it is concerned with the formation of hypotheses where empirical evidence is still lacking. It conceives that all knowledge is scientific knowledge, to be ascertained and proved by the methods of science”…This is a good definition of materialism. Plekhanov would take it as his own. Engels would agree with that. Every one of the French materialists would sign some such declaration, but, lo! it was taken from Mr. Bertrand Russell’s Philosophy in the Twentieth Century.6

The doubting reader may now shake his head. Is that really materialism? Does not materialism boast of knowing what matter really is, of reducing everything to atoms? Did not Mr. Edward Bernstein, for instance, one who is supposed to know what materialism is, express the essence of materialism when he said, “the materialist believes only in atoms?” Edward Bernstein certainly said it, hundreds of others also said it, but it is not true. D’Holbach, the author of the Syeteme de la nature, who we may assume also knew what materialism is, has this to say: “We do not know the essence of any object, if by essence is to be understood that which constitutes its own inner nature, we know matter only by our sensations of it and ideas about it.”

…”Matter is for us that which excites, in one way or another our external organs; and the properties which we ascribe to matter are based on the different impressions and changes that it produces in us,” and further: “we know neither one essence, nor the true nature of matter, though we are capable of ascertaining some of its properties and qualities, in relation with its influence upon us.”

And here is La Mettrie, that “Enfant perdu” of materialism as Plekhanov calls him; what has he to say about this materialistic dogmatism, that the “belief in atoms” solves all problems? This is what he has to say: “The essence of the human and animal soul is unknown to us, and will always remain unknown, just as the essence of matter and bodies. But though we do not know the essence of matter, we are nevertheless compelled to acknowledge (as real) those properties (i.e., of matter) that it uncovers to us through our external organs.”7

Do these statements assert that “we believe only in atoms” or the dogmatic belief in matter, which is ascribed to materialism?

Plekhanov has called the philosophy of Mach “cowardly idealism.” This could just as well be applied to Mr. Russell’s own philosophy, as well as to the whole school that is known as “neo-realism.” Driven by modern science towards materialism, they cannot accept that thoroughgoing discipline which materialism requires. Mr. Russell is, for instance, very bitter against idealism. Idealism he believes leads to solipsism, but in his book, Our Knowledge of the External World, he himself eliminates physical objects from the world, and to the question: what remains, of what is the universe constituted? he replies: It is composed of sense data, but some data are not physical, not material objects, hence the idealism that was driven out through the door, comes in again through the window. Even his Analysis of Mind, where he has made a few more steps in the direction of materialism, is an “unfinished” work; the “cowardly idealism” accompanies him always. “To destroy matter was to feel the soul,” Berkeley said; to affirm the reality of matter is to destroy the soul. The neo-realist dilemma is how to destroy the soul, and yet preserve it. These philosophers would feel just as uncomfortable entirely without the traditional soul as with it.

The materialist is a thorough-going scientific realist. He does not compromise; he finds no place in the universe for anything spiritual that is not a property of matter. The fact that we do not know what matter really is in itself, does not drive the materialist back to idealism. It leads him instead to the laboratory. “If we derive the scheme of the universe,” says Engels in his Anti-Duhring, “not from our own brain (as the idealist does) but merely by means of our own brain, from the material world then we need no philosophy, but simply a knowledge of the world and what occurs in it, and the results of this knowledge likewise do not constitute a philosophy, but positive science.”8

It is true, of course, that the old materialism was often very metaphysical; some have sinned against it by creating “systems.” French materialism of the eighteenth century had many faults and shortcomings. It was non-evolutionary, mechanical.

It has left no psychology. It could not apply its own theories to the explanation of social and historical phenomena, but this was not the fault of the individual philosophers: they were simply the children of their age. Materialism enriched with the results of modern science, materialism without any metaphysical dogmatism, blended with the newer psychology and sociology, must become the philosophy of today. In the works of Marx, Engels, and Plekhanov were laid the foundations for such a philosophy; to bring it in conformity with that wealth of science that has accumulated since their time, is our task today.

NOTES

1. I quote Professor Marvin simply because I have his by no means bad book before me. His view of materialism is typical of most, if not of all other professors of philosophy.

2. Body and Mind: a history and defense of animism by William Mcdougal. P. 1.

3. G.V. Plekhanov: Collected Works (Russian), Vol. 18, pp. 299-302.

4. Reconstruction in Philosophy, by John Dewey, chapter first.

5. We have now in mind exclusively metaphysical materialism; historical and dialectic materialism, will be discussed separately.

6. See Sceptical Essays, by Bertrand Russell, p. 71.

7. G.V. Plekhanov: Beitrage zur Geschichte des Materialismus; also Vol. II of his collected works. (Russian.)

8. Landmarks of Scientific Socialism, by Frederick Engels.

Modern Quarterly began in 1923 by V. F. Calverton. Calverton, born George Goetz (1900–1940), a radical writer, literary critic and publisher. Based in Baltimore, Modern Quarterly was an unaligned socialist discussion magazine, and dominated by its editor. Calverton’s interest in and support for Black liberation opened the pages of MQ to a host of the most important Black writers and debates of the 1920s and 30s, enough to make it an important historic US left journal. In addition, MQ covered sexual topics rarely openly discussed as well as the arts and literature, and had considerable attention from left intellectuals in the 1920s and early 1930s. From 1933 until Calverton’s early death from alcoholism in 1940 Modern Quarterly continued as The Modern Monthly. Increasingly involved in bitter polemics with the Communist Party-aligned writers, Modern Monthly became more overtly ‘Anti-Stalinist’ in the mid-1930s Calverton, very much an iconoclast and often accused of dilettantism, also opposed entry into World War Two which put him and his journal at odds with much of left and progressive thinking of the later 1930s, further leading to the journal’s isolation.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/modern-quarterly_november-1928-february-1929_5_1/modern-quarterly_november-1928-february-1929_5_1.pdf