Joseph Berger on U.S. imperialism’s first forays into the ‘Middle East’ against what was its chief rival as well as ally in the 1910s and 20s where it played ‘democrat’ to Britain’s Empire. No surprise, oil had much to do with it.

‘The Advance of the United States against the British ‘Middle East’’ by Joseph Berger from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 7 No. 68. December 1, 1927.

The quest for oil wells and cheaper cotton is, apart from the striving for favourable fields for capital investment, the main driving force of imperialism in that extensive area which, in the terminology of British colonial politicians, is described as “the Middle East,” and the territories stretching from the Western frontier of India, over Afghanistan, Persia, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Arabia, Egypt and the Sudan down to Abyssinia. Since the end of the war, British imperialism has maintained the undisputed lead in the great race of the rivals in the “Middle East”. Great Britain has not only secured the political rule, or at least the decisive influence in all these countries (if we disregard the very shaky French domination in Syria and the insignificant influence of Italy in Yemen) and in this way built the famous “land bridge” to India or at least set up its scaffolding but also British capital is far in advance economically of that of its rivals.

The attempts of the other European competitors, so far as they related immediately to oil wells or securing areas for cotton planting, were everywhere comparatively easily defeated. The French were palmed off with a small percentage of the Mosul oil; the Italian appetite in Abyssinia was sated for the time being by the agreement of 1926, which aroused great excitement at the time, as well as by small slices of territory at the cost of Egypt and in Southern Arabia.

During the past year, however, a new competitor has made its appearance, which is equipped with incomparably greater means than any of the European States, has a correspondingly greater appetite and is therefore by far the greatest danger for British economic imperialism: the capitalists of the United States are stretching out their hands after the Middle East.

It should be pointed out at the same time that this new rival of British imperialism is for the time being proceeding very cautiously, slowly and tentatively. The foreign policy of the United States at present reflects only to a quite unnoticeable extent the activity of the economic combines, hence the greater the activity of these combines themselves.

When a British company obtained the concession for the exploitation of the oil wells on the Farsan islands (in the Red Sea, west of the coast of Asir) participators from the United States were at the same time on the spot. Finally, the exploitation was undertaken by a British and an American company jointly. United States capital is participating in the oil wells recently discovered on the West coast of the Red Sea, on Egyptian territory, and which are said to be fairly rich.

In the year 1926 a number of engineers from the United States were very busy in Southern Palestine and in Trans-jordania making borings after oil. In November 1926 capital from the United States was likewise taking part in the borings for oil commenced by the French in the Alaquiten district.

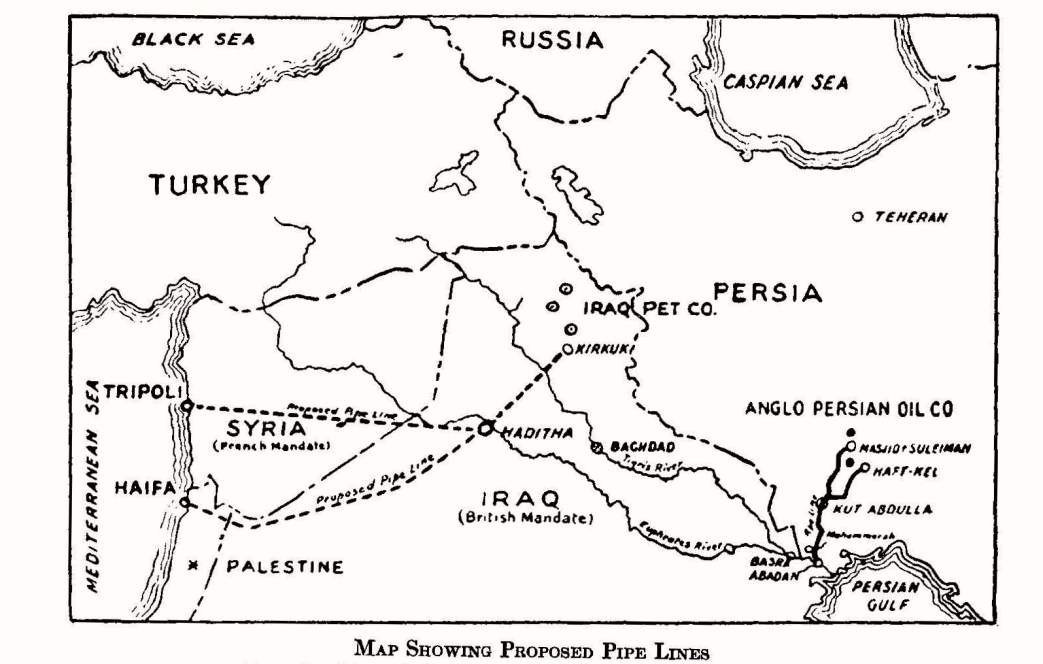

A specially fierce struggle was waged in the course of the last few years between the Turkish Petroleum Company, representing British capital (Shell concern with Deterding at the head), and the Standard Oil Company (American oil capital) for the exploitation of the oil fields in Iraq, particularly in Mosul. It was only in the last few weeks, after all the attempts of the British to keep out the Standard Oil had failed (the declaration of the British Under Secretary of State in Parliament that Mosul oil is only a legend, that there exist no supplies of oil in Iraq worth speaking of, which declaration made the rounds of the European press in the Summer of this year, seems according to this declaration to have been, only an episode in the fight of Deterding against Standard Oil!), that an agreement was arrived at, which means in fact a victory for the American claims (the Americans obtained 25%).

In Persia, too, the American companies are constantly pushing their way against the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

When one considers all these facts one obtains a picture of the advance of the Americans against the British Middle East in the sphere of exploitation of mineral oil. This picture is now supplemented by the American advance in Abyssinia, which in the last few days has occupied the centre point of interest and throws a bright light on the second sector of the American economic front the cotton interests.

Only recently there appeared from authoritative sources a report that the American White Corporation had concluded a contract with the Abyssinian government for the erection of a dam on the Blue Nile at the place where this leaves Lake Tsana. This useful engineering undertaking is said to render possible the irrigation of vast areas of land in Abyssinia which are to be given over to the cultivation of cotton.

The excitement which spread in Egyptian political and business circles on account of this news is quite understandable when it is pointed out that the quantity of Nile water necessary for irrigating the cotton areas in Egypt would experience a considerable reduction by the building of a dam on an arm of the Blue Nile. The fact that the English laid claim to 300,000 feddans of land in the so-called Djesirah (island between the Nile tributaries in the Sudan) for cotton planting, already seriously threatened the water supply of Egypt. The double danger of lack of water for the Egyptian cotton plantation and the competition of the cheaper Sudanese cotton (the low prices in Sudan are attained by a terrible exploitation of the plantation workers who have to toil like slaves) is the chief reason why the Egyptians always place the Sudan question in the fore ground of all negotiations with Great Britain. The building of a dam at Lake Tsana will increase this danger for Egypt still further.

But this will be a danger not only, and not in the first place for Egypt. More exact investigations of the quantities of water supplied by Lake Tsana show that the chief danger of a dam at Lake Tsana is directed not so much against the Egyptian cotton plantations, which receive only a tenth of their requirements of water from the arm of the Nile in question, but much more against the plantations of the British Cotton Growing Association in Sudan.

This circumstance immediately gave the American dam project an anti-British tendency. It was then remembered that Great Britain possesses a treaty concluded with the Abyssinian government as early as 1902, according to which British firms are to have the preference in the construction of a dam. It was officially (by Chamberlain) and semi-officially asserted that Abyssinia would not grant a concession over the head of Great Britain, that the question still remains open and that Britain must at least be assured a share in the carrying out of this project.

The White Corporation contented itself with simply repeating that the concession is a matter which has already been concluded. The representative of Abyssinia (in Adis Abeba, the capital of this country, a General Consulate of the United States is to be established shortly), on his part, calls attention to the fact that Abyssinia, after Great Britain a year ago concluded an agreement with Italy behind the back of the Abyssinian government (which is still a member of the League of Nations) aiming at the dividing up of Abyssinia, was compelled to look round for better and more reliable “friends” than Great Britain.

For the United States again the penetration of Abyssinia has great importance: it frustrates the British plan of making the textile industry of Manchester independent of United States cotton (as well as that of Egypt) by means of extensive plantations in the Sudan. It renders possible vast prospects for capital investments in Central Africa, which still remains to be opened up. At the same time it enables the United States to exert decisive influence on the further course of politics in the Middle East, for the Lake Tsana concession provides the key not only to Abyssinian but also to Egyptian politics.

The hopes cherished by a great part of the Egyptian nationalist movement in the United States are now receiving definite encouragement. Just at the moment when the negotiations between Sarvat Pasha and Chamberlain were approaching their culmination, a new factor makes its appearance the United States. The agitation which the Wafd conducted in the United States was one of the most important factors which expedited the formal recognition of the independence of Egypt by Great Britain in the year 1922.

Since then the United States has not let slip any opportunity to express its special position towards the Egyptian nationalist movement and its rejection of the privileged position of Great Britain in Egypt. The Ambassador of the United States, Dr. Martin Howell, emphasised his hostility to “British imperialism” and his sympathy for Zaglul Pasha, his conviction that Egypt is ripe for real self-administration and for independent choice of its advisers (who even now must still be drawn from the circle of British officials) so strongly that he had to be recalled.

But that did not in the least alter the fundamental attitude of the United States to the Egyptian problems. The American imperialists insist that an alliance with the United States is not at all dangerous for Egypt, because the United States is not aiming at territorial expansion: it is more concerned with regulating the cotton market.

The advance of the United States now gives Egyptian policy two possibilities: either to uphold the joint Anglo-Egyptian interests, to create an alliance with Great Britain against the American danger, as is proposed by the organ of the Ittehad party and the Liberal Constitutional Party (Sarvat), or to incline towards the United States, to oust the English from the Sudan and thereby achieve independence, as is advocated by a portion of the Zaglulist and nationalist press.

In any event the affair of the Lake Tsana dam, like the question of Mosul oil, reveals the rivalry between Great Britain and the United States in the Near East which appears to be gradually becoming the centre-point of the political situation in these two countries.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1927/v07n68-dec-01-1927-inprecor-op.pdf