Joseph Berger begins his analysis of Iraq under the British mandate with its internal class relations.

‘Class Differentiation in Iraq’ by Joseph Berger from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 25. April 1, 1926.

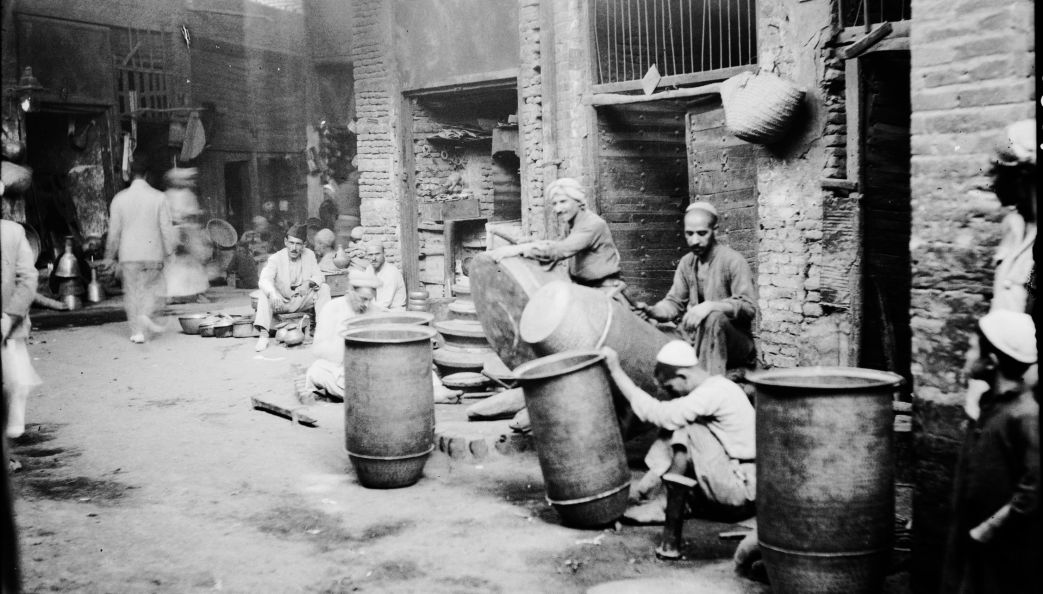

In the time preceding the war, Iraq the territory between the Euphrates and the Tigris, which is now under an English Mandate was, under the rule of the Turkish Sultans, culturally one of the most backward provinces. The land (especially the southern part) is distinguished by its great fertility, and although the contrast between the rich landowners and the small tenants was fairly pronounced in the country, the reciprocal relations were nevertheless of a patriarchal, idyllic character. This was still more marked in the towns, where the inhabitants were largely occupied in trade or handicrafts, to the exclusion of all industry.

The war completely altered this state of affairs. Iraq became a theatre of war, first German and then English troops devastated the country. The poorer strata of the population, the small peasants, were those who suffered most: they were completely ruined. The Pashas and large landowners, who had previously sided with the Turks, very soon made peace with the new English Power. The broad masses of the people however were soon driven to revolt by the distress which prevailed amongst them. In 1920 there was a serious insurrection in which, apart from the Bedouin tribes, the urban population chiefly took part, and it was only with great difficulty that Great Britain mastered this revolt. No less than 9000 insurgents were killed.

Great Britain then set up an “Arab” King, King Feisul, to rule in Iraq. The whole clique of Pashas and Begs grouped themselves round Feisul and rendered obedient service to England. This however immediately produced an intensification of class antagonisms in the Arab population itself. The Nationalists, who are supported by the poor population of the towns and by the peasantry, could not fight against England, the archenemy, without at the same time attacking Feisul and his Pashas. The idyllic condition quickly came to an end. The uppermost stratum became more and more intimately allied with the ruling English officials and even abandoned Arab customs and observances in order to ape the English. The Pashas sent their sons to English Universities and sold their land to the English Generals and Commissioners at banquets and gymkhanas. Amongst the lowest strata on the other hand, indignation and hatred of the rich, classes spread in ever-widening circles. To this must be added that the English are inclined to turn the fruitful country of Mesopotamia into a peasant colony and the small peasants into plantation slaves. In the North, in the Mosul district, the thousands of small peasants who are losing their land are induced to work at the petroleum wells. In this way, a rural and urban proletariat is being created.

The antagonism between the classes in Iraq has found its clearest expression in the last few months when two questions of vital importance to Iraq have been under discussion: the Mosul question and the question of the Anglo-Iraq Treaty. The question was whether Iraq should join England against the young Turkish Republic, or should join the latter against English imperialism. The Pashas and Begs did everything possible in order to turn the people against Turkey. In doing so they made use of the demagogic argument of identifying the new Turkey with the old Turkish despotism, and emphasised the necessity of a “national” resistance to the Turks etc. The broad masses of the people nevertheless would not allow themselves to be led astray. When the news was received that Mosul was included in the English Mandate, there were, at the same time as the triumphal parades of the official authorities, stormy anti-English demonstrations in Kirkuk, Mosul and other towns, which could only be suppressed by the military. (The English news agencies of course maintained dead silence with regard to these manifestations!)

A few weeks later, the Anglo-Iraq treaty was to be ratified by the so-called “Parliament”. The Pashas were in such terror of a popular movement against this treaty, the purport of which was the enslavement of Iraq for twenty years, that they wanted to discuss the treaty in a secret sitting of Parliament. The Opposition protested against this and was supported by the crowds which had collected in front of the parliament. The Government summoned the police, had the recalcitrant members of Parliament removed by force, dispersed the assembled crowds and Parliament passed the treaty in the course of a single night in a secret sitting.

This however is by no means the end of the fight. On the contrary, as the distress among the people increases in consequence of the predatory rule of English imperialism (in Iraq. villages which pay no taxes are bombarded by English aircraft…). in the same measure is the class-consciousness of the lower strata intensified and even larger masses are joining the national revolutionary movement against the English and the clique of King Feisul and his Pashas, which is supporting them.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n25-apr-01-1926-Inprecor.pdf