Today’s online flame wars are liberal dinnerparty-agnosticism in comparison to the late-1910s-early-20s multi-sided debate among Black radicals. The old fights, however, were infinitely richer. Here, a leading voice in that debate challenges Marcus Garvey and the idea that a Black capitalism could ever compete, let alone survive, in a world of monopolistic imperialism.

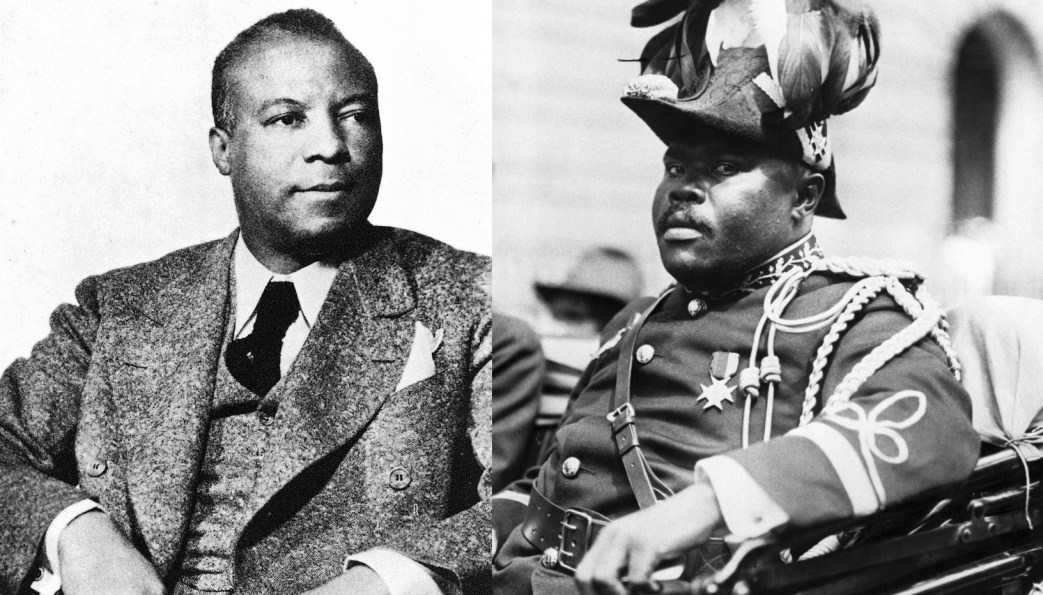

‘Garveyism’ by A. Philip Randolph from The Messenger. Vol. 3 No. 4. September, 1921.

GARVEYISM is an upshot of the Great World War. It sprang forth amidst the wild currents of national, racial and class hatreds and prejudices stirred and unleashed by the furious flames of battle. Under the strains and stresses of conflict, the state power and institutions of the ruling peoples were mobilized. The intelligensia of the Central Powers apotheosized “Mittel Europa,” Kultur, the Bagdad Railroad, and hurled imprecations upon the heads of the ungodly Entente. So, in turn, the high priests of morals and propaganda of the holy Allies sang a hymn of hate to the tune of the “Hun.”

“Britania, Britania Britania rules the waves, Britons will ne’r be slaves,” “self determination of smaller nationalities,” “revanche, Italia irridenta,” “100 per cent Americanism,” “we are fighting to make the world safe for democracy,” “Deutschland Uber Alles,” “Pan-Slavism,” etc., were the psychological armor and spear of Armageddon. Add to this psychic complex of blatant, arrogant and hypocritical chauvinism the revolutionary, proletarian internationalism of the Russian Revolution: “no annexations, no punitive indemnities and self-determination for smaller nationalities,” and it is at once apparent how nationalisms, racialisms, and classisms, strangled and repressed in the cruel and brutal grip of imperialism, under the magic and galvanic stimulant of such moving slogans, would struggle to become more articulate, more defiant, more revolutionary.

The Easter Rebellion of Seinn Feinism, in 1916; Mahata Gmandhi’s non-co-operative philosophy of outraged India; Mustapha Kemal Pasha’s adamant stand at Angora in the Levant, battling for a conquering, militant Pan Islamism; the erratic vagaries of d’Annunzio for a re-united Italy; together with the rumblings of unrest in Egypt and among other oppressed peoples, attest to the manner in which the war quickened the vision of hitherto adjudged backward peoples, and set free forces making for the overthrow of the institutions and the abolition of the conditions that gave it (the war) birth. Indeed, the war was fruitful of paradoxes. Movements grew both for and against the interest of society. Imperialism and revolution faced each other. The Kremlin and the Quai d’Orsay of the worker and capitalist, respectively, seemed to grow in power. Movements grotesque and sound, appear to flourish and decay for the nonce.

All of these varied and variegated associated efforts have their rooting in the sub-soil of oppression and fear. The oppressed struggle to be freed; the oppressors fear their struggles. Hence, movements for liberation, whether they function through a sound methodology or not, are reactions to age-long injustices; they are reflexes of the universal urge for human freedom.

In the light of these principles, it is clear to anyone that Garveyism is a natural and logical reaction of black men to the overweening and supercilious conduct of white imperialists. Garveyism proclaims the doctrine of “similarity.”

To the fallacy of “white man first” Garveyism would counter with a similar fallacy of “Negro first.” If there be a “White House” in the Capitol of the nation, why not a Black House also; if there be a Red Cross and an American Legion, why not a Black Cross and a Black or Negro Legion, says the movement. And at the summit of this doctrine of “similarity” stands the African Empire as a counter-irritant to the white empires, monarchies and republics of the world. Out of this doctrine it is, indeed, not strange that transportation should partake of the magic romanticism of color. Why do persons ask, then, why a Black Star Line? And this is not said in a vein of levity, for whatever might be said of the Garvey Movement, it, at least, strives for consistency.

A word, now, concerning the doctrine of “similarity.” Upon its face, it would appear to commend itself as a sound and logical course of action. Upon closer examination, however, one is largely disillusioned. It is hardly scientific, too, to make a sweeping condemnation of this doctrine on the grounds of its absolute inapplicability to the highly complex problems of the Negro. The stock argument raised by its proponents is that: “if a given thing is good for a white man, that very same thing is also good for the Negro. By this token of argument the conquest of Africa with a view to establishing an African empire, a Black Star Line, etc., is justified.

The fallacy of this logic consists in its total disregard of the relative value of the thing proposed to those for whom it is proposed. To illustrate: it does not follow that because there are subways in New York City owned and operated by white people that there should also be a subway in New York City owned and operated by Negroes. For in the first place it couldn’t be done (the enthusiasts who proclaim the patent inanity that there is no such thing as “can’t.” to the contrary notwithstanding) and, in the second place, even if it could be done, it would be an economic injury instead of a benefit. The reasons for this are clear. The subways, elevated trains and surface lines are owned and controlled by the same financial interests. They are of the nature of a monopoly. These interests exercise great influence upon the City Administration which grants franchises to public utilities. Hence, a competing public carrier could not secure the necessary privilege; nor would the Money Trust extend the requisite capital, recognizing the inability of such a competitor to secure the same through the tedious and protracted method of small stock sales to an innocent public. Granting, however, that the necessary capital could be raised, a subway so established would immediately be thrown into bankruptcy through the rate cutting of fares by the older concern. The history of American business is replete with the failures of enterprises that have attempted to buck the big monopolies and trusts. The process has been that either a small competitor is absorbed or driven out of the field by the big syndicates. And when a small business is permitted to exist, it is decidedly against the interests of the public, because being unable to do large scale buying, to engage in extensive advertising, to employ the most highly skilled technicians of hand and brain, and to institute the most modern and scientific methods of economy, it is forced to sell its services or goods to the public at the highest price obtainable. In other words, a business which sells to 1,000 persons a day can sell at a lower price than the one which sells to only 100, because it buys more at a lower price. Such is the great advantage of the monopoly or trust over the small business. Of course, the trusts are robbing the people because they have the ability to raise prices at will. But they are the most efficient institution for producing and marketing goods and services yet devised.

What is true of transportation within cities is also true of transportation between cities. No sane business promoter would think of advising anyone to invest in an enterprise to construct a railroad to compete with the great Pennsylvania, or Grand Central railway systems. Such a venture by people of color for people of color, in the circles of experienced and intelligent business men, would only be regarded as a joke. Obviously, from a business point of view, such aforenamed undertakings are unsound. If they are unsound business enterprises, by what stretch of the imagination and race patriotism could they be justified as a phase of the solution of the Negro problem? Certainly, an intelligent person would not advocate an admittedly unscientific and inefficient plan of action in industry, business or finance, on the highly questionable grounds, that Negroes should have such an enterprise of their own and for their own. For, palpably, no benefits can flow to a people from the adoption of a program which the collective intelligence of society has discarded. Again while it is sometimes true that one profits from failures; it is also true that one may be destroyed by failures. Nor is it sufficient to counter with the argument that one must go through certain experiences in order to learn. There is abundant evidence to show that experience is the most extensive and inconvenient method of acquiring knowledge. No one will contend that it is necessary to take bichloride of mercury in order to ascertain whether it will really cause death or not. The purpose of scientific research is to place, at the convenience of society, a body of knowledge which will make it unnecessary for every one to go through the same painful and protracted process of discovering and organizing the same.

The accumulated knowledge of business economics, if consulted, would convince anyone of the folly today, of trying to build a new business with limited capital and limited brains, in a highly trustified field such as, the railroad and shipping industries.

In the “Annalist” of August 15th, 1921, S.G. Riggs, writing on the subject “Past Experience Gives Shipping a Gloomy Outlook,” says, “that only one-fourth of the Governments ships are in operation, and there is about 33 per cent of the tonnage tied up in the world.” He further makes this significant statement: “On June 30, 1914, there were 45.4 million gross tons of steamers in the world; today there are close to 54.8 million tons, a 20 per cent increase. On the other hand, the quantity of cargo moving is one-fourth less than in 1913, as has been proved by a compilation of imports and exports of twenty leading countries. A number of fine crafts are being laid up and many more will have to follow, for at the figures at present ruling many voyages do not pay actual outgoing expenses, leaving nothing for interest and depreciation. [A citation of editorials during the years from 1897 to 1900 which he uses as typical of editorials of the shipping journals today.”]

In conclusion, he says, “that shipping is facing a long, severe depression with little chance of an upward movement for years.”

Such is the sober opinion of an expert of the shipping business.

In other words, today great shipping interests backed up with unlimited capital, with fleets of ships, (not makeshifts nor apologies) are hard put to it to make ends meet, on account of the supply of ships being greater than the demand. It is safe to say that no expert in the shipping business would advise even one with unlimited capital and skilled operators, to begin a brand new shipping business today, or to continue one if it is possible to stop without incurring a greater loss than by continuing.

In view of the foregoing facts, it is difficult to understand how any group of alleged intelligent and honest Negroes can continue to hold out the hope to well-meaning hut misguided Negroes that they will build a great fleet of ships, plying between America, the West Indies and Africa, carrying Negroes and their Cargo.

The shipping business is controlled by a Shipping Trust.

It is about as possible and necessary to maintain a fleet of ships for Negroes only, as it is to build and maintain a railroad alongside that of the Pennsylvania railroad for Negroes only.

This is the excuse for the Black Star Line according to Mr. Garvey, as reported in the Negro World of Aug. 20, 1920:

“You know of the insults heaped upon Negro passengers on the steamships of other lines when those Negroes were able to secure passage on them. You know of the weeks and months they have been compelled to wait to secure passages from one place to another. The Black Star Line aims to remedy all this, but we must have ships, more and bigger ships.”

It might not be unkind to ask how many Negroes do or can make use of ocean travel?

Now as to the matter of empire.

First, what is the status of Africa today? According to the International Relations Series, edited by G. Lowes Dickinson, the area of Africa is about 11.500.000 square miles, and its population about 170 millions. “By 1914 the whole continent, with the exception of Abyssinia (350,000 square miles and eight millions population) and Liberia (area 40,000 square miles, population two millions), had been subjected to the control and government of European states,” writes Dickinson. The following figures show what shares the various States took in this partition:

Area—Population

France 4,200,000–25,000,000

Britain 3,300,000–35,000,000

*Germany 1,100,000–12,000,000

Belgium 900,000–7,000,000

Portugal 800,000–8,000,000

Italy 600,000–1,000,000

Spain 750,000–200,000

*(Now in the hands of Great Britain)

The foregoing figures will indicate just how much vacant, available territory exists in Africa today.

Since, then, there is no unclaimed land in Africa, the logical question to ask is: how does one expect to build an empire there?

Here again, we will let the chief spokesman of Garveyism speak. Says he, on August 20, 1921, according to the Negro World, its official organ:

“It falls to your lot to tear off the shackles that bind Mother Africa. Can you do it? (Cries of ‘Yes! Yes! You did it in the Revolutionary War; you did it in the Civil War; you did it in the Battle of the Marne; you did it at Verdun; you did it in Mesopotamia; you did it in Togoland, in German East Africa, and you can do it marching up the battle heights of Africa.”

At this point it will be logical and sane to examine the relative power of the forces that control Africa and of those that propose conquering it, in order to ascertain the folly or wisdom of the enterprise.

The aforementioned powers are equipped with big dreadnoughts, submarines, aeroplanes and great armies. In modern warfare Lewisite Gas is said to be capable of destroying entire cities. Aeroplanes have been built that can carry a half-ton gas bomb. Modern artillery was instrumental in producing a deathlist in the great world war of nearly 10,000,000, together with nearly 30,000,000 wounded. The imperialists nation in Africa control all of the death-dealing engines of power.

The very fact that the great European powers have fought to conquer Africa, is pretty good evidence that they don’t intend surrendering it to the cry of “Africa for the Africans.” Thus, it means war to the death against the formidable armies and navies of the great powers in Africa. The Garvey forces haven’t a single fighting craft. They have no military organization; no military or naval leadership. How then can Negroes conquer Africa? Someone says, “We will take the arms from the white man.” This, I submit, is not the most reassuring and delightful task.

But, it is apparently understood that the Negroes’ conquering Africa is a mere dream. For proclaims the leader:

“All of us might not live to see the higher accomplishment of an African empire so strong and powerful, as to compel the respect of all mankind, but we in cur lifetime can so work and so act, as to make the dream a possibility within another generation.”

Loss of hope appears in the distance.

A word about the value of Garveyism to Negroes today. It has done some splendid things. It has inculcated into the minds of Negroes the need and value of organization. It has also demonstrated the ability of Negroes to come together in large masses under Negro leadership. Of course, the A.M.E. Church has done as much; so have the Negro Secret Orders. Garveyism, also, has conducted wholesome, vital, necessary and effective criticism on Negro leadership. It has stimulated the pride of Negroes in Negro history and traditions, thereby helping to break down the slave psychology which throttles and strangles Negro initiative, self-assertiveness, ambition, courage, independence, etc. It has further stiffened the Negroes’ backbone to resist the encroachments and insults of white people. Again, it has emphsized the international character of the Negro problem. As a propaganda organization, at one period of its history, it was highly useful in awakening Negro consciousness to the demand of the times.

But its business operations, as exposed by Dr. Du Bois, to which I have not as yet seen a convincing reply, have not been conceived altogether in harmony with approved, modern business economics. That Negroes should develop business enterprises is correct. To this there can be no intelligent objection. But the kind, at certain times, seems to me to be highly material. Also, that Garveyism has stimulated Negro business initiative, no fair-minded person will gainsay.

But the crux of Garveyism is the redemption of Africa, the building of an African Empire. This can not be defended as an immediate program of the Negro, in the light of modern world politics. The slogan “Africa for the Africans” no Negro, or for that matter liberal white man, will oppose; but “back to Africa” for the conquest of Africa is a different song.

The white mobocratic South, with its Tom Watsons, Cole Bleases, and John Williamses could not wish for a better ally than Garveyism, at this time. How is that, you ask?

It has been a recognized form of strategy of the ruling class in every country that whenever the discontent of the working people became a menace to them (the ruling class) that they (the ruling class) either started a war of aggression or invited a war of invasion. This was done to divert the attention of the masses from the causes of their poverty and misery at home to some imaginary foreign enemy. Witness the old Nobility of Russia today urging an invasion of their own country by foreign powers. During the Revolution in France 1789 to 1793, the old Feudal aristocracy invited the invasion of France by foreign nations.

In America, the problem of the Negro is a labor problem. Negroes constitute a laboring element. Unrest is widespread among them, even in the South. Radical white labor groups are reported to be calling to them. Washington, Chicago, Arkansas and Tulsa race riots show that Negroes are discontented and are ready to strike back. The increasing demand of Negroes for the abolition of the jim-crow car, disfranchisement, lynching; the insistence of a small minority for every right, even social equality; the trend of Negroes into labor unions; the activities of Negroes in the Socialist movement–all indicate the birth of a new consciousness.

Now to divert the Negroes’ mind away from these fundamental problems is to weaken them and strengthen the Bourbon forces of the Negro-hating South and the exploiting capitalists of America.

This is why there is no opposition to the demonstrations of Garveyism, either in parades or public mass meetings in the Armory or Madison Square Garden.

Negro Socialists, on the other hand, are thwarted in their every attempt to conduct public educational meetings, and parades would be out of the question. The cry would go up: Anarchists, they want to overthrow the government by violence! Such is the smoke screen used to suffocate real radicalism.

The whites in America don’t take Garveyism seriously. They dub Garvey a “Moses of the Negro” in order to get Negroes to follow him, which will wean them away from any truly radical economic program. They know that the achievement of his program, the redemption of Africa is unattainable, but it serves the purpose of engaging the Negroes’ brains, energy and funds in a highly nebulous, futile and doubtful movement so far as beneficial results to Negroes are concerned.

Think of the solution of Garveyism for the present wave of unemployment!

Says Mr. Garvey in a recent speech, according to the Negro World:

“If you are employed by white men and they choose to dismiss you because of color tell him, “Brother, you remember the last war; all right, an other one may come.” That is your trump card. You are not begging for jobs; you demand jobs because you made it possible for them to live in peace (Cheers), otherwise the Germans would have been at their door. You have a fair exchange for the money that is given to you. Let them know this: that your future service depends upon their present good treatment.

This is doubtless a rejoinder to the charge brought against the movement, viz., that when Negroes applied at certain business, or industrial plants for work, they were told to go to Mr. Garvey, the Negro King.

While it is absurd to charge Garvey with the plight of the Negro in the country today; yet what individual with the slightest conception of industrial problems, would accept the aforegoing statement of Mr. Garvey as a remedy for the Negroes’ unemployment? It is not only childish, but it accentuates, and complicates the Negroes’ difficulties by making the question of unemployment an issue as between white and black men, when, in fact, it is a product of the capitalist system which brings about overproduction at certain cycles, and consequent unemployment of workers regardless of race, creed, nationality or color. In very truth, a strikingly anti-white man doctrine is both unsound and dangerous. For it is false to assume that all white men are agreed upon a program of opposition to Negroes. The dominant groups America, as in other parts of the world, are class groups. All white men are not in harmony with respect to human action and human institutions. The Great World War demonstrated that. Debs in jail is also proof as strong as “holy writ.” Strikes and lockouts on the industrial field indicate a difference of class interests within the same race. Also the fights between Negro tenants and Negro landlords show that even Negroes may have different interests. In fact, the interests of a Negro tenant and white tenant are more in common than the interests between white tenants and white landlords or Negro tenants and Negro landlords.

Thus, Garveyism broadens the chasm between the black and white workers, and can only result in the creation of more race hatred which will periodically flare up into race riots.

However, with the elimination of the African program, the “Negro First” doctrine, the Black Star Line, the existing organization of Garveyism may be directed into some useful channel.

The Negro public is facing so serious a period that it should demand that the different schools of Negro thought come before it and present their programs. The programs should be examined and criticized by the Negro public so that it might accept or reject according to the merits or demerits of the different schools.

It was, indeed, astounding to read the following part of a resolution adopted on the Pan-African Congress meeting in Paris, at a public meeting of the U.N.I.A.:

“That we believe the motives of the congress are to undermine the true feeling and sentiment of the Negro race for complete freedom in their own spheres and for a higher social order among themselves, as against a desire among a certain class of Negroes for social contact, comradeship and companionship with the white race.

“We further repudiate the congress because we sincerely feel that the white race, like the black and yellow races, should maintain the purity of self, and that the congress is nothing more than an effort to encourage race suicide by the admixture of two opposite races.

“That the said W.E.B. Du Bois and his associates, who called the congress, are making an issue of social equality with the white race for their own selfish purposes and not for the advancement of the Negro race.”

Now, certainly, no one will accuse the MESSENGER of any bias in favor of Dr. Du Bois. But here the Negro is faced with the rejection of a principle which has been the ardent hope of the South since Reconstruction–the principle of social equality. Can Negroes accept the stigma of inferiority upon the pretext of keeping the stock pure? By the way, no anthropologist, worthy of the name, would advocate the purity of ethnic groups by preventing miscegenation.

Further, to reject and condemn a principle on the ground that some one is using it to selfish ends, is as sensible as it would be to oppose the teaching of writing to Negro youth, because it has been used for forgery or that those who lynch Negroes use it. The issue is the value of an instrument for the achievement of certain ends. To reject social equality is to accept the jim-crow car, disfranchisement, lynching, etc. Without social equality the Negro will ever remain a political and economic serf.

Garveyism is spiritual; the need now, however, is a Negro renaissance in scientific thought.

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/1921-09-sep-mess-RIAZ.pdf