For generations the redneck miners of West Virginia’s Kanawha Valley, with their determined, costly struggles were viewed with the greatest respect, even awe, by worker militants across the country. After the bitter defeats resulting after the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921, the U.M.W.A. collapsed in the bituminous belt, with only Southern Illinois remaining unionized. Here, Illinois miner and labor journalist McAllister Coleman travels to West Virginia as the U.M.W.A. attempts to rebuild its organization in the state.

‘Kanawha’s Fighting Rednecks’ by McAllister Coleman from Labor Age. Vol. 14 No. 2. February, 1925.

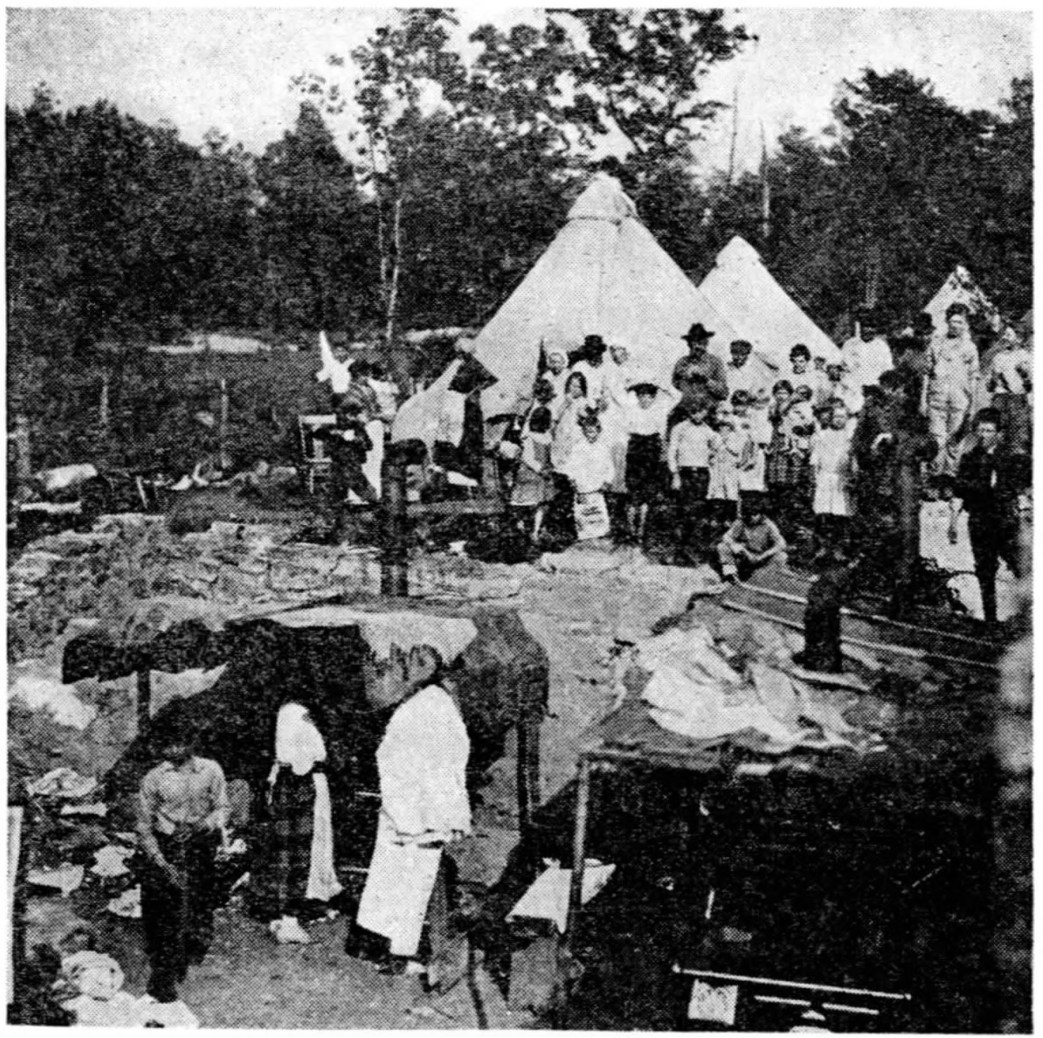

KANAWHA’S Rednecks are only a section of the great industrial army of fighting men who have bivouacked in tent colonies through the years of American history. The miners and their women have battled as few other groups have battled in this country of ours for freedom. As inspiring an example as that of the men at Valley Forge has been given in Wyoming, in Colorado, in the Pennsylvania hills, in Bloody West Virginia—wherever the men from under the face of the earth have come out into the daylight to demand a fuller share of our American life.

Eviction and Tent Colonies Dot American Labor’s Battlegrounds.

West Virginia is in a peculiar way the pivotal ground in the struggle between the Coal Barons and the Miners. If it fails to be won, the great Labor Giant will be seriously hampered in any future nation-wide efforts at democracy in his industry. If the Coal Barons are beaten, on the other hand, then can the men from underneath extend their democracy and eventually win the day for progress

“What,” asked the horse-dealer of the smoking-car at large, “is a two-letter word meaning Egyptian sun-god?”

When a cross-word veteran had introduced him to that nationally known divinity, Ra, he looked up from his paper for a moment out on the bare hills that skirt Cabin Creek on the way to Charleston, West Virginia. Through an opening in the hills one could see gray ribbons of smoke twisting up from the tents of evicted union miners.

“I hope them red-necks freeze to death,” said the horse-dealer cheerfully, “we don’t want no unions in this part of the country.” He was back again the next moment fumbling through a somewhat limited vocabulary for a two-letter word meaning “behold.” And there was no more talk about evicted miners or the perils of unionism.

In fact, it’s this Chinese-like indifference to the progress of an industrial war that is being waged at their very door-steps that seems to an outsider characteristic of the attitude of the rank and file of the citizens of West Virginia and surrounding states where the United Mine Workers of America are fighting against industrial autocracy. It isn’t just that the non-union operators have long since held control of the machinery of politics and propaganda. Down in Logan County today there is a very healthy revolt going on against the reign of Don Chafin, the union-baiting sheriff who has kept union organizers out of his county by use of a private army of deputy sheriffs subsidized by the operators. But those who are foremost in the fight against the Don of Logan openly state that they have no sympathy with unionism. Because they want to get rid of Don and his gun-toting deputies does not signify that they will welcome organizers come down from union headquarters at Charleston.

The Shut-Ins.

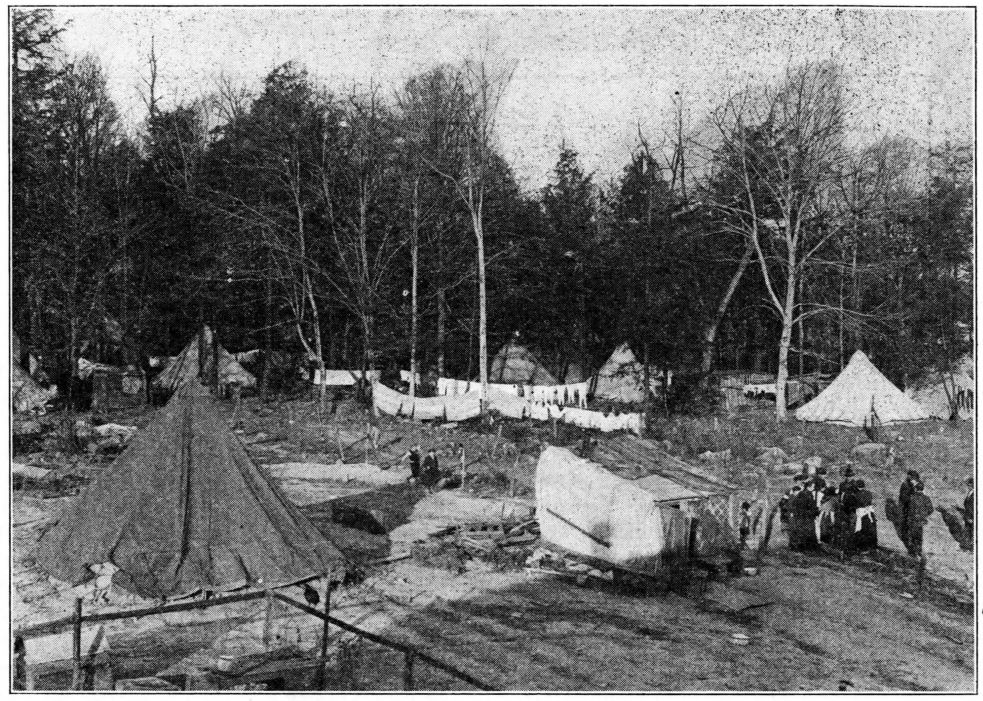

In my work with coal-diggers in Illinois, Pennsylvania and Oklahoma, I have always been impressed with the isolation that cuts the miner off from contacts even with his own world of labor outside the field. In West Virginia today this isolation is given keen edge by the complete silence of the local press on matters connected with the strikes and lock-outs that have been going on for three years. So far as I could find out, no social agencies go near the women and children of evicted miners, some of whom are in dire need of food, clothing and decent shelter. The church has preserved its wonted aloofness. The average citizen may not go so far as the smoking car horse-dealer, but he neither knows nor seems to care about what happens down the long Kanawha Valley or in the fields to the north where twenty’ thousand men, women and children are forced to turn to the union for relief in the shape of tents and barracks and rations enough for bare existence.

To me it is as thrilling and important a struggle as Organized Labor has made in this country for many years. There is something quite tremendous about the spirit of those union people, the majority of them American-born, who feel in their hearts that they are fighting for fundamental human rights and who have stayed out there in tents and lean-to’s, some of them for three years now, because they will not work for what amounts in many cases to a thirty-eight per cent cut in wages.

They want the Jacksonville contract with its living wage and union recognition and every Sunday afternoon, rain or shine, they leave their tents with the American flag carried up ahead and someone blowing on a bugle, to march past the company houses. The non-union men and their families come out to stare curiously at these little processions that go slipping and sliding on the muddy roads through the valleys.

It’s rarely that the marchers fail to win recruits. Men who have just taken the union obligation with evictions staring them in the face tell you that they would just as soon starve out on the hills as work for the operators for scrip, for they insist that after they have paid the various operators’ check-offs for the company store, the company doctor, the company minister and in some instances the company detectives, they have nothing left. “Of course we keep alive,” these non-union men tell you, “but that’s about all.”

A Heart-Breaking Business.

Little by little under the cool and business-like direction of Percy Tetlow, head of District 17, U.M.W. of A., the latest union drive that has the Kanawha Valley as its spearhead, is working its way to the non-union fields to the south, to Logan and Mingo and McDowell counties.

A heart-breaking and expensive business, this providing shelter and food and keeping up the morale of thousands of coal-diggers who are facing the rigors of a hard winter, but it’s a job that must be done if the United Mine Workers are to go forward. All through the coal fields of the Central Competitive District in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania, idle union miners are watching loaded coal trains roll through their territory from the nonunion fields south of the Ohio River.

In Illinois, for example, not only are the West Virginia operators favored by freight rate differentials, but they are paying $3.50 or less for day men as compared with a $7.50 rate paid the Illinois mine workers. An operator who is willing to pay a living wage and recognize the union is hard put to it to make both ends meet when he has to face such competition. Whatever temporary schemes may be considered, the central problem just now of those who head the coal-diggers is to bring West Virginia and surrounding territory under union conditions.

Starve-—But “No Scabbing!’’

That is why the headquarters of District 17 in Charleston is such a busy place these days. There organizers are checking up the ration requests sent in by chairmen of local relief committees, there trucks are being loaded with army tents to give shelter to the men, women and children who are daily being turned out into the cold by deputy sheriffs armed with dispossess notices. The union is pouring thousands of dollars a month into West Virginia, but all of this is not enough to put shoes on the feet of the kids, give warm clothing to the women. As a consequence there is real suffering in the tent colonies, suffering that is borne for the most part in grim silence.

“I tell you, young man,” said a tall, raw-boned wife of a miner who was trying to get dinner on a cook-stove in a leaky tent and at the same time keep four small children in order, “it’s no fun keeping house in one of these here army tents. But if you aim to write a piece about all this, you put it down that we ain’t going back. Not until we get our rights, we ain’t. If I was to think for one minute that my man would go to scabbing, I’d quit him cold.”

There was the same spirit under every rain-soaked tent which I entered. The women, who as usual bear the brunt of the fight, are 100 per cent union. The wife whose husband will work non-union is a social pariah.

It is a long and bitter struggle that is going on down there in the West Virginia hills. If these coaldiggers stick, if all that deputy sheriffs and mineguards and the elements can do fail to drive them back to the mines, labor will have won one of the most glorious struggles in its history.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v14n02-feb-1925-LA.pdf