Kantorivitch defends the historical materialism of Marx against the vulgar materialism of the ‘Beard School’ and its ‘Marxist’ echoers.

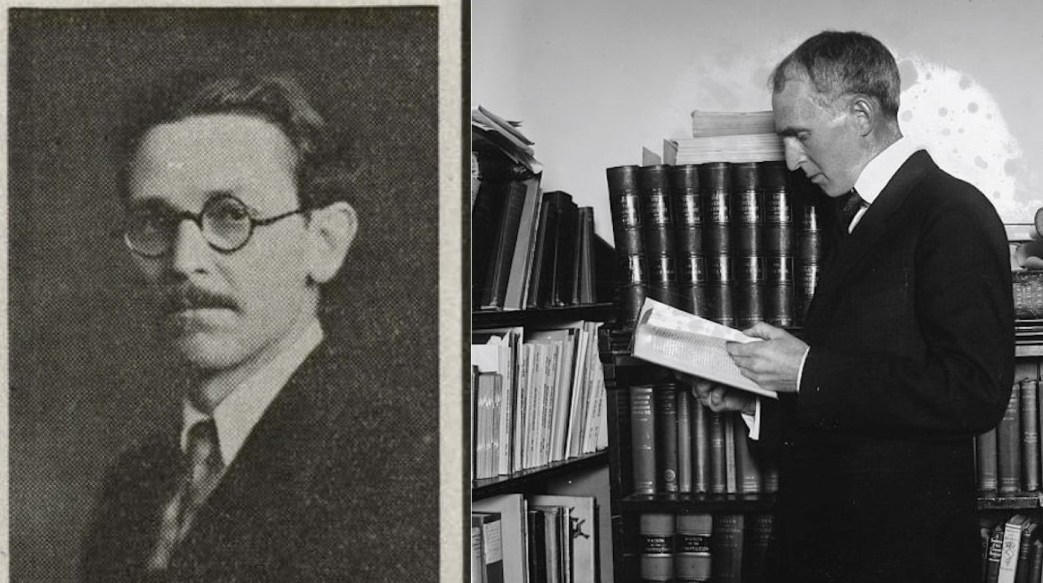

‘A Modern Analysis of Historical Theory’ by Haim Kantorovitch from Modern Quarterly. Vol. 2 No. 2. Fall, 1924.

I.

The bourgeois professors, writers, and politicians still look at historical materialism as something that is not worth serious consideration. It is true that historians and sociologists are beginning more and more to take notice of the economic factors in social life and evolution, but they never mention Marx or Marxism in their writings. Even Charles A. Beard, interpreting American history from an economic standpoint and desiring to make clear his method, tells his readers that the best representative of this economic method is Professor Edwin R. Seligman. Professor Beard knows, of course, that what Seligman did was to write a popular booklet on the historical theories of Marx, without adding anything of his own. But even as a popularizer of Marx’s theories, Professor Seligman cannot be taken seriously, because any one who is acquainted with Marxism can see that Professor Seligman did not understand its real nature, that he only repeats the popular catch-words of socialist agitators, and reproduces all the vulgar misrepresentations of historical materialism that can be found in popular propagandistic literature, socialist as well as anti-socialist. This “popular misrepresentation” of Marxism became the foundation for the historical interpretations of Beard and many others.

We should rather be thankful to these historians that they do not call themselves Marxians: the quarrel is not with them, but rather with those who call them Marxians.

What, for instance, is Professor Beard’s economic interpretation of history? It consists in the vulgar assumption that behind the actions of every individual there are economic motives. Everybody has his own well-being at heart. Take, for example, his interpretation of the United States Constitution. He brought together in this book a mass of facts to prove that the makers of our Constitution really represented only their private interests at the Constitutional Convention. Of course, I neither doubt nor depreciate these facts; on the contrary, every impartial reader will admit that they are true, and no one will, of course, doubt their value. Nevertheless, in themselves these facts do not explain history. The method of Beard is the method of economic determinism. Though this method is accepted and advocated by many socialists and given out as pure Marxism, it is really the opposite of Marxism.

The starting point of economic determinism is the conviction that human actions, that is, the actions of individuals, are determined solely by their economic interests. If this be true, we must make another step and declare also that these conscious motives are behind every action of every individual, that every individual acts consciously according to his interests. There is of course nothing new in this theory; this is simply Utilitarianism with a mixture of economics. Bentham’s statement that “on the occasion of every act he exercises, every human being is led to pursue that line of conduct which, according to his view of the case, taken by him at the moment, will be in the highest degree contributory to his own greatest happiness” can serve as a good definition not only of Utilitarianism but of economic determinism. One may of course mistake his interests, or miscalculate his actions, but if he does understand his real interests he will always act in accordance with them. In his book “Socialism Positive and Negative,” R.R. La Monte makes this very clear. La Monte is of course not the only socialist writer who holds to this theory; we find it expressed or implied in nearly the whole of American socialist literature; and the worst of it all is that according to tradition they call it scientific, and never neglect any opportunity to express their pride in the statement that they have done away with Utopianism and are now, thanks to Marx and Engels, scientific. Whether or not economic determinism is scientific does not interest us at present. What we are interested in is to show that it has really nothing to do with the social philosophy of Marx and Engels.

People act according to their interests. We will leave out for the present the question of whether it is really possible for an individual to be conscious of the real motives of his action. Let us see instead what it does mean to act according to one’s own interests. It cannot mean anything else than that people do what is good for them. We find this thought very frequently expressed in socialist literature: “If the workers will only understand their interests they will abolish capitalism, they will find out that capitalism is bad for them, and socialism good,” and because people always act according to their interests, they will become socialists and eventually bring about the Social Revolution. What is implied here is that socialism really rests on ethical evaluations, that it is a question of good and bad. Is that the Marxian conception of socialism? By no means. On the contrary, it is exactly what Marx and Engels called Utopianism. To the Utopian neither capitalism nor socialism was a historical necessity, for them it was a question only of good or bad. If capitalism is bad, why do we have it? Because people misunderstand their real interests. What are we to do, we who have at last found what the real interests of men are? We are to make them understand their real interests, and they will establish socialism. Marx and Engels fought against this theory. Engels says: “Marx has never based upon this (the conceptions of good and bad, just and unjust, etc.) his communist conclusions, but rather upon necessary overthrow, which is developing itself under our eyes every day, of the capitalist society.”¹

The modern socialist movement dates from the eighteenth century. This, of course, does not mean that there were no socialist ideas and theories before then. Kautsky began his history of socialism with Plato’s Republic; Pohlman and others found socialist theories existing even long before this time. A comparison of Utopian socialism with Marxism will show us clearly not only the difference between Utopian and Marxian conceptions of socialism, but also the difference between economic determinism and the materialistic conception of history.

None of the Utopians cares much for philosophy in itself; none of them has ever undertaken a critical examination of the philosophic principles which they accepted as the basis of their respective social theories. They have borrowed these principles from the French Materialists of the eighteenth century; along with these principles they also accepted their mistakes and the many glaring contradictions that abounded in the works of their masters.

The French Materialists of the eighteenth century believed that man, his relations, his intellect, his ideas and conceptions are nothing else than the transformation of sensations, that is, they are the results of the influence of environment. “Man is wholly what education makes him to be” said Helvetius. They were also careful always to make

it clear that by environment was meant the whole complex of social life. It is clear that if the ideas of every man be determined by his social surroundings, the ideas of men (the human race) must be determined by the historical development of these surroundings, or, in other words, by the history of social relations. If we ask them why the human intellect has developed, we should have to find first what were the changes in the social relations of men that determined and called forth the changes in their ideas.

The important question, then, before the French Materialists was: What determines the evolution of social relations? They are certainly not causeless. In this they leave metaphysics for sociology. But in their sociology the French Materialists were very unfortunate. Whenever they had to account for the evolution of social relations, they always, without exception, replied, “Opinions govern the world.” Man’s own mistakes have made him unhappy, says d’Holbach. We find ourselves in a bewitched circle.2 Man and his opinions are products of social relations; social relations are the product of men’s opinions. There is no way out, we are back at the beginning, searching for a solution of this antinomy, a solution that cannot be found in the writings of the French Materialists.

The Utopian socialists, in addition to borrowing their metaphysical principles from the French Materialists, borrowed also their contradictions. In their fight against the upholders of the present order of society they had to answer two objections: 1) Nature has created men, good and bad, able and unable, talented and untalented, and thus it must always remain. 2) Because of the first reason, there is no way to rebuild society. To the first objection they replied that man is wholly the product of social environment; it is social conditions that make man good or bad. By changing society you will change men’s morals and conduct. To the second objection they replied that men are the masters of their own faith. They are themselves responsible for everything that is bad in social life; they have themselves created this objectionable social order and they have done it because they did not know how to organize a better society. But now since I, the Utopian, have conceived of a plan for the reorganization of society on a more rational basis, a social order in which all the objectionable traits of modern society have been eliminated and men will have a chance to live freely and happily, it is only necessary to convince people as to the logicality and efficacy of the new plan.

They did not appeal to the poor nor to the workers, but to the rich and the powerful. Robert Owen sent his plans to kings, ambassadors and powerful Statesmen. Fourier waited daily for the arrival of a millionaire who would offer his fortune to establish the new order, and Saint Simon, the most original and profound thinker of them all, appealed to the rich “to do their duty toward their poor brethren.” That it was possible to convince the rich and powerful they never doubted for a minute. In their conception of truth they were absolutists. They believed that it was possible for the human mind to discover such absolute truths that would hold good under all circumstances, in all ages, and for people in all walks of life. Capitalism for them was wholly bad, socialism wholly true. The only problem before them was how to convince humanity that they had really succeeded in discovering this truth. They thought that the best way to convince people was through practical experiments and they therefore spent most of their energy in establishing socialist colonies: oases in the capitalist desert.

Of all the classes to whom the Utopians appealed one was absolutely excluded–the proletariat. The working class at that time was in an embryonic state. The workers were not conscious of themselves as a class; they were poor, unorganized and uneducated, and nothing could be expected from them.

II.

The opposite of Utopian socialism is Marxism, opposite in tactics as well as in philosophy.

During the period that elapsed between the Materialists of the eighteenth century and the origin of the Marxists, many things happened. Natural science, having been largely extended, enriched and widened the horizon of human knowledge; the theory of evolution had become definitely established and had given a great stimulus to many thinkers; historical research had demonstrated the idea of social evolution, and with it the relativity of all truth. But above all, the workers became conscious of themselves as a class, they began to organize, to conduct a conscious class-struggle. The times were revolutionary. “In 1842 England witnessed the first strike on a large scale…that bore a political revolutionary character; in 1843 and 1844 the idea of an impending revolution was widely spreading in England; in 1844 an insurrection broke out among the Silesian weavers; in 1845 and 1846 socialism spread rapidly on all sides in Germany…The spectre of communism was abroad in Europe.”3 The working class movement did not wait for a theory to justify its rise; it came, and after it came it began to search for a theory that should embody its experience with the intellectual currents of the times. Marx, in a letter to Ruge as early as 1843 stated his program in the following words: “We do not…proclaim to the world in doctrinaire fashion any new principle. This is the truth, bow down before it…We only make clear to men for what they are really struggling, and to the consciousness of this they must come whether they will or not.”3 In other words, Marx and Engels only aimed to interpret in the light of science and philosophy the class struggle that was already raging openly all over Europe.

In this they were greatly helped by the eminent German philosopher, Friedrich W. Hegel. Hegel could really apply to himself the words of Faust: “Oh, two souls struggle within me,” for on the one hand Hegel’s philosophy is mystic; he bases all his system on the absolute idea that has come from nowhere and goes to nothing, that this self-created idea developed in itself and for itself and incidentally created the universe and caused all actions of humanity. Neither Hegel, nor any of his pupils, could say what this absolute idea was, or even what they understood by it. But this was in truth only Hegel’s masque under which was hidden the real Hegel, Hegel the realist, Hegel the evolutionist, who revolutionized science through the elaboration of his method of dialectic logic. It was Hegel the realist, Hegel the father of dialectic logic that attracted Marx and Engels.

What was the Hegelian dialectic method? First of all it was a revolt against traditional logic, which was rigid and scholastic. Traditional logic believed in eternal laws, that things and beings that are found in the world are divided into kinds, species and classes. All is fixed, constant, eternal. Traditional logic remained, as it was found by Aristotle, as the description of the process of human thought. The dogmas of traditional logic that seemed to be eternal and immutable were: the principle of identity that A equals A; the principle of contradiction that A cannot be A and not A; and the principle of the excluded middle that A can only be A or not A. Against these Hegel revolted: there are no abstract, eternal, immutable truths, he declared. There are no separate things; the universe is one whole, and everything depends on many other things, and you can know it only in relation to other things. As a thing itself, out of its surroundings it is only an abstraction. This is also the case with the conceptions of goodness, truth, beauty, justice, etc. There are no such abstract things as truth, or beauty, or justice. A thing may be good in one instance and bad in another. If one wishes to know whether a thing be good or bad, he must first be clear as to the questions: Good for whom? Good when? Good under what circumstances? A thing may be good and bad at the same time, because it becomes good for one while it becomes bad for some one else.4 Contradiction is the principle of life. There are contradictions in everything, and that is why everything will in the course of its history develop into its opposite. Without this contradiction there would be no progressive evolution.

But evolution through contradiction is not the only revolutionary element in Hegel’s dialectics. Just as important is his conception of evolution as prefatory to revolution. Traditional logic, as well as the science of evolution in Hegel’s time, “believed that there are no sudden leaps in nature, and it is a common notion that things have their origin through gradual increase or decrease…But there is also such a thing as sudden transformation from quantity into quality.” Evolution goes on by quantity, and when the quantity reaches a certain limit, through a revolution it is suddenly transformed into a new quality.

Marx and Engels accepted this method, made it their own, and with its help formulated the laws of evolution of society. But Hegel was an idealist. Dialectic evolution for Hegel was the evolution of the absolute idea. Marx and Engels turned away from idealism and became materialists, but for them it was possible to escape the contradictions of the former materialists because they enriched their materialism with the dialectic method. The problem before Marx and Engels in the beginning was to get rid of Utopianism. As dialecticians they first of all discarded all those eternal truths of which Utopian socialism was redolent. There are no absolute truths. Is socialism good? Is capitalism bad? No, says Marx, this is not the way to put the question. We should ask: When is capitalism bad, and for whom? because it is obvious that a thing may be good at one time and bad at another, good for one man and bad for another. What are we to do then? We must first of all find out the objective laws of social evolution. We must find out how society develops and what are the tendencies of its present development. Hegel, Marx and Engels believed that social evolution goes on through objective laws which cannot change. Now what are these laws?

In his preface to his book “A Critique to Political Economy” Marx related how he came gradually to the formulation of his historical theory. “The general conclusion at which I arrived and which, once reached, continued to serve as the leading thread in my studies may be briefly summed up as follows: In the social production which men carry on they enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will.” You will remember that neither the Utopians nor the French Materialists could account for the social relations of man, and declared them to be the results of man’s opinions. Not so with Marx–he learned from Hegel that social change is independent of man’s will, that man enters into definite relations that are inevitable, that these relations are not of his choice, and, when the Utopians declare that we have a bad social order only because man has not understood how to organize society on a better basis, the Marxist replies, “Here you are mistaken, these social relations are independent of our will; social orders do not arise because we want them to, neither can they be abolished because we don’t like them.”

What are these relations if they are independent of our will? “They are relations of production,” replies the Marxian, and these “relations of production correspond to a definite stage in the development of the material powers of production.” In order to live man must produce. “The social relations are intimately attached to the productive forces. In acquiring new productive forces men change their mode of production, and in changing their mode of production, their manner of gaining a living, they change all their social relations. The windmill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam mill society with the industrial capitalist.”5 Again in the preface to his contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx says: “The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political, and spiritual process of life.”

The development of society, then, follows the development of the material forces of production. We must remember that these forces are always changing. If we accept the theory of geographic and climatic forces as causes of social change, will it help us in any way to understand, let us say, American history? By no means. Have the geographic and climatic conditions of America changed much since the Civil War? No. Nevertheless, during this time America has changed more than it could have changed before in centuries. An eighteenth century American would not recognize it now. American social life, ideals, literature–in short, what may be called the American national psychology has changed together with the development of the material forces of production. New tools of production, new machinery, new ways of working mines, of producing the necessary means of life, the development of the modern factory, the trade union and socialist movement that arose as its results, have entirely changed the face of America.

But one can say that new tools of production are invented by man’s mind and the mind then is the chief factor in social evolution. We come again to the statement that society is governed by opinions. “It is not the consciousness of men that determine their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness.” That this is true has been demonstrated not only by Marxists, but by hundreds of bourgeois historians and sociologists, and lately also by the followers of the new psychology. Take for instance the history of inventions and it iwll be seen that no invention has ever been made unless there was a social demand for it, and further that in order to make an invention, the inventor must make use of the social means of production at his command. Moreover, the inventor himself must have a thorough and intimate knowledge of how his invention is going to be used, and he therefore must know how people now produce the same results without his invention. In other words, he must be acquainted with the productive process in which his invention will be used. John Dewey says:

“As the arts and crafts develop and become more elaborate, the body of positive knowledge enlarges…Technologies of this kind give that common sense knowledge of nature out of which science takes its origin. They provide y not merely a collection of positive facts, but they give expertness in dealing with materials and tools, and promote the development of the experimental habit of mind.”6

Human mind and human thought are products of the social relations in which they developed and by which they are stimulated. It is true that, as Marx says: “Men make their own history,” and in order to make it, they must desire it, but is their will free or causeless? No. Their will is determined by the economic situation in which they live, and by the class to which they either belong or join.

From the materialist conception of history, Marx and Engels reexamined the history of human society and found that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”7 Society has always been, and is now, divided into classes. When we say that man’s intellect is the result of his social surroundings we must remember that man, the individual thinker, is a member of a certain class. Every philosophy or system of thought, as well as every work of art reflects not only the conditions, but also the desires, aspirations or interests of a particular class. We therefore are justified in speaking not only of class ideology but of class psychology. A capitalist intellectual may be honestly distressed by the cheerlessness and ugliness of the workers’ lives, which he observes on slumming parties, but he does not see that any more can be done after making a few laws in favor of labor, and establishing a few more settlement houses. Socialism he is sure is a good thing, but it can never be established. He is, of course, intellectually not inferior to any socialist, and is usually superior to the average worker, but upon reading Marx, he will come to the conclusion that it is futile. Why? Because he is psychologically unprepared, because his conditions of life, his education, and his social interests have developed in him an individualistic psychology.8 Socialism even as an idea is contrary to his method of thinking. On the other hand, take a modern worker. His psychology is collectivistic: in the factory where he works he has hundreds of comrades that are working for the same concern, suffering the same wrongs, having the same interests, the same friends and enemies, and when you speak to him of socialism, he may not understand it, but he feels its truth. The modern factory has created all the prerequisites of the workers, because “it is not consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.”

III.

Marx and Engels and all who have given themselves the trouble to study and understand Marx, always make a careful distinction between class interest and class psychology. These are two separate concepts that do not always coincide. Class interests of course influence to a very great extent the class psychology of man, but, only by influencing man’s psychology, by becoming transformed in the human mind as ideals, can they ever become motives of action. For illustration: We all believe that social- ism is for the interests of the working class, but many thousands of those who sacrificed their lives for socialism (especially in Russia) did not believe in the theory of the class struggle; thousands of these heroes never read a book on socialism, and hundreds of members of the Social Revolutionary Party of Russia were violently anti-Marxian. But why say only anti-Marxians? Did not the Social Democrats sacrifice their lives on the barricades or go joyfully to Siberia because it was in their economic interests, or even because they were conscious that it was in the interests of their class? Of course not. To the individual socialist, socialism is a purely subjective ideal, an ideal so true and so beautiful that it pays to sacrifice one’s life for it. He does not think about economic interests while dying, or in prison, but of the moral beauty, of the new human civilization for which he is fighting. Marxians understand and appreciate this and what they say is that back of their psychology are the material interests of a certain class. It should be noted that Marx never wrote of the material interests of the individual, but of that of the classes only.

Class psychology is the immediate cause of class actions, but where do class interests enter? What is their role in social life? They determine the content and form of human psychology. Of course every Marxist says this, but nevertheless the economic determinist is wrong; first, because we know that the economic interests that determine human psychology are not the interests of individuals but of classes, and secondly, and more important, is that, admitting the determining power of “class” economic interest we nevertheless deny that they force every individual to act consciously in accordance with his own economic good.

Modern psychology, especially the psycho-analytic, is very proud of its discovery of the unconscious as a motive power in human life, and a certain school has gone so far as to say that if the only thing to remain of Freud’s psychology is the concept of the unconscious, it will be enough to earn him a place among the immortal benefactors of the human race. But in reality Freud was not the first to make use of unconscious motives in order to explain human actions, neither was Von Hartman, who some psychologists claim is the father of this conception. Marx and Engels used this concept long before any of them. It is true that they have written no books on the unconscious, nor have they often touched on any purely psychological subject. They were social philosophers, and psychology, a science that was very little developed at that time, interested them only in its bearing on sociology. Nevertheless, every Marxian student knows that the concept of unconscious motives is one of the fundamental principles of historical materialism. The material class interests always determine the psychology, but the particular class has never been conscious of it. The Marxist declares that all religious wars were wars for material interests, but that does not mean that the individuals who participated in these wars were consciously lying when they declared that they were fighting and sacrificing themselves for religious ideals. By no means, says Marx, because it only shows that man is rarely conscious of the real motives behind his ideas, beliefs and convictions. These will only be discovered later, by the social psychologist.

Why then did not the class interests of the proletarians of the ancient world turn their psychology to socialism? Because, says Kautsky, and Marx likewise would make the same statement–socialism was not possible at that stage of social development, and “man always puts such aims before him as can be realized.” That simply means that class interests are always co-determinants, together with all the other material factors. Why was Christianity accepted by the Jewish and Roman proletariat? Because the circumstances were such that there was no possibility for the amelioration of their conditions, and this fact created a psychologic predisposition towards mystical ideas, towards such teachings that comforted them with the home of a future world beyond the present. There were at that time many mystic advocates of suicide, and they also represented the proletarian class psychology–not because suicide was in the interests of the poor, but because there was no other way for men to hope except to put their faith in a life after death or despair.

When we say that we base our socialist hopes on the growing class consciousness of the worker, we mean only to say that economic conditions in general are such that the psychology of the workers is becoming more and more socialistic even now under capitalism, and that capitalism has created such conditions that the class interests and class psychology of the proletariat coincide.

“At a certain stage of their development, the material forces of production in society come in conflict with the existing relations of production, or, what is but the legal expression of the same thing, with the property relations within which they had been at work before.”9

This is just what we have today. The property relations are individualistic, while the development of the material forces of society have made production collectivistic. We have here a contradiction, a thesis and antithesis. What happens then? “Then comes a period of social revolution,” the thesis and anti-thesis are united in a synthesis,–in our case, socialism.

There are inherent contradictions in everything, some contradictions are of no consequence, as, for instance, the contradiction that life and death always go together. But, on the other hand, there are contradictions of great value, as factors in social development. Analyzing capitalist society, Marx and Engels found that there is an inherent contradiction in capitalism, a contradiction that must lead to the death of this system.

“In proportion as the bourgeois is developed, in the same proportion is the proletariat, the modern working class developed, a class of laborers, who live only so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labor increases capital. With the development of industry the proletariat not only increases in number, but it becomes concentrated in greater masses, its strength grows. The workers begin to form trade unions but they soon find out that the real fruit of their battles lies, not in the immediate results, but in the ever expanding union of the workers. The proletariat then captures the state, constitutes itself as the ruling class, and uses its political supremacy to wrest by degrees all capital from the bourgeoise and establishes socialism.”

This is the evolution of history, as the materialist and sociologist must see it. The increasing ferocity of the struggle between capital and labor is irrefutable proof of this phase, “the ever expanding union of the workers” phase, of the process. The future will confirm the conclusion.

NOTES

1. Page 14, Preface, Misery of Philosophy.

2. G. V. Plechanoff: Beitrage zur geschichte des Materialismus.

3. Life and Works of Marx, by Beer, Page 39.

4. See “Morals and Determination”, Vol. 1, No. 4, The Modern Quarterly.

5. Poverty of Philosophy, English translation, page 119.

6. For clarification of the moral issue see “Morals and Determination”, by V. F. Calverton, Reconstruction of Philosophy, page 12.

7. Communist Manifesto, page 12.

8. Of course, there are exceptions, all however which are traceable to unusually powerful motives, early affections and friendships, associations in youth with opposite cliques, etc.

9. Preface to the Critique of Political Economy, page 12.

Modern Quarterly began in 1923 by V. F. Calverton. Calverton, born George Goetz (1900–1940), a radical writer, literary critic and publisher. Based in Baltimore, Modern Quarterly was an unaligned socialist discussion magazine, and dominated by its editor. Calverton’s interest in and support for Black liberation opened the pages of MQ to a host of the most important Black writers and debates of the 1920s and 30s, enough to make it an important historic US left journal. In addition, MQ covered sexual topics rarely openly discussed as well as the arts and literature, and had considerable attention from left intellectuals in the 1920s and early 1930s. From 1933 until Calverton’s early death from alcoholism in 1940 Modern Quarterly continued as The Modern Monthly. Increasingly involved in bitter polemics with the Communist Party-aligned writers, Modern Monthly became more overtly ‘Anti-Stalinist’ in the mid-1930s Calverton, very much an iconoclast and often accused of dilettantism, also opposed entry into World War Two which put him and his journal at odds with much of left and progressive thinking of the later 1930s, further leading to the journal’s isolation.

PDF of full issue: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112001580031?urlappend=%3Bseq=423%3Bownerid=13510798902032684-451