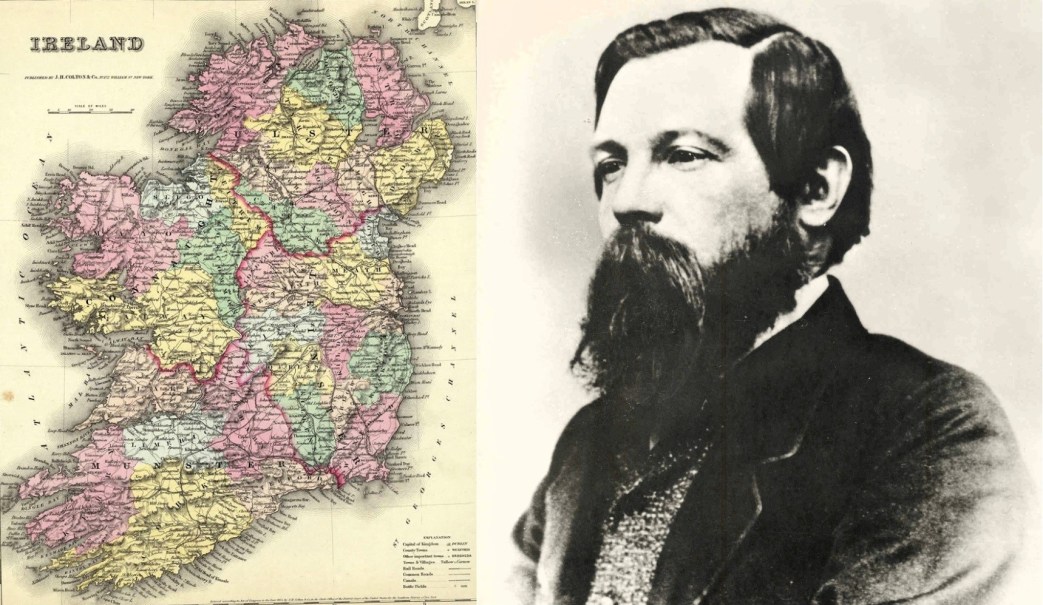

Both Marx and Engels were connected politically and socially to Ireland, Engels also intimately. In the first of three visits to the country, he traveled with his partner Mary Burns, born to Tipperary parents, from Dublin to Galway and down the West Coast where the consequences of the 1840s ‘famines’ were very much in evidence. Returning to Manchester, Engels wrote Marx of his impressions.

‘Visit to Ireland’ (1856) by Frederick Engels from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Selected Correspondence, 1846-1895. International Publishers, New York. 1936.

Manchester, 23 May, 1856.

In our tour in Ireland we came from Dublin to Galway on the west coast, then twenty miles north inland, then to Limerick, down the Shannon to Tarbert, Tralee, Killarney and back to Dublin. A total of about four to five hundred English miles in the country itself, so that we have seen about two-thirds of the whole country. With the exception of Dublin, which bears the same relation to London as Dusseldorf does to Berlin and has quite the character of a small one-time capital, all English built too, the whole country, and especially the towns, has exactly the appearance of France or Northern Italy, Gendarmes, priests, lawyers, bureaucrats, squires in pleasing profusion and a total absence of any and every industry, so that it would be difficult to understand what all these parasitic growths found to live on if the misery of the peasants did not supply the other half of the picture. “Strong measures” are visible in every corner of the country, the government meddles with everything, of so-called self-government there is not a trace. Ireland may be regarded as the first English colony and as one which because of its proximity is still governed exactly in the old way, and here one can already observe that the so-called liberty of English citizens is based on the oppression of the colonies. I have never seen so many gendarmes in any country, and the drink-sodden expression of the Prussian gendarme is developed to its highest perfection here among the constabulary, who are armed with carbines, bayonets and handcuffs.

Characteristic of this country are its ruins, the oldest from the fifth and sixth centuries, the latest from the nineteenth—with every intervening period. The most ancient are all churches; after 1100, churches and castles; after 1800 the houses of peasants. The whole of the west, but especially in the neighborhood of Galway, is covered with these ruined peasant houses, most of which have only been deserted since 1846. I never thought that famine could have such tangible reality. Whole villages are devastated, and there among them lie the splendid parks of the lesser landlords, who are almost the only people still living there, mostly lawyers. Famine, emigration and clearances together have accomplished this. There are not even cattle to be seen in the fields. The land is an utter desert which nobody wants. In County Clare, south of Galway, it is rather better, here there are at least some cattle, and the hills toward Limerick are excellently cultivated, mostly by Scottish farmers, the ruins have been cleared away and the country has a bourgeois appearance. In the southwest there are a lot of mountains and bogs but also wonderfully rich forest growth, beyond that again fine pastures, especially in Tipperary, and towards Dublin land which is, one can see, gradually coming into the hands of big farmers.

The country has been completely ruined by the English wars of conquest from 1100 to 1850 (for in reality both the wars and the state of siege lasted as long as that). It is a fact that most of the ruins were produced by destruction during the wars. The people itself has got its peculiar character from this, and despite all their Irish nationalist fanaticism the fellows feel that they are no longer at home in their own country. Ireland for the Saxon! That is now being realised. The Irishman knows he cannot compete with the Englishman, who comes with means in every respect superior; emigration will go on until the predominantly, indeed almost exclusively, Celtic character of the population is all to hell. How often have the Irish started to try and achieve something, and every time they have been crashed, politically and industrially! By consistent oppression they have been artificially converted into an utterly demoralised nation and now fulfil the notorious function of supplying England, America, Australia, etc., with prostitutes, casual laborers, pimps, thieves, swindlers, beggars and other rabble. This demoralised character persists in the aristocracy too. The landowners, who everywhere else have taken on bourgeois qualities, are here completely demoralised. Their country seats are surrounded by enormous, wonderfully beautiful parks, but all around is waste land, and where the money is supposed to come from it is impossible to see. These fellows ought to be shot. Of mixed blood, mostly tall, strong, handsome chaps, they all wear enormous moustaches under colossal Roman noses, give themselves the sham military airs of retired colonels, travel around the country after all sorts of pleasures, and if one makes an inquiry, they haven’t a penny, are laden with debts, and live in dread of the Encumbered Estates Court.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.227457/2015.227457.Selected-Correspondence.pdf