A superlative piece of proletarian reporting from a veteran stockyard worker, and Socialist, on the history, technique, economy, and conditions of Chicago’s giant meatpacking industry.

‘The Beef Trust on Trial’ by Anton Rudowsky from International Socialist Review. Vol. 12 No. 9. March, 1912.

WHEN Upton Sinclair published his book, “The Jungle,” about seven years ago, it caused profound consternation among the American packing companies. And it was no wonder. Thousands and hundreds of thousands of men and women became temporary vegetarians. The decline in the exports of meat and meat products was phenomenal. As this decline followed closely after the big strike of the packing house workers in 1904 in Chicago, Kansas City, Omaha and other places, it was explained that the falling off in sales was probably due to the revolt of the workers. At last, by order of Terrible Teddy, the Government made its own investigation in the packing plants—to reassure the public, strengthen the market and save the packers from further enormous losses. The Government report corroborated all the allegations contained in the “Jungle,” but also. showed what great and wonderful changes had taken place in the packing industry. They said the plants were clean and that a hundred government inspectors were on the job every day inspecting the animals as well as the dressed meat so that no impurities would be likely to get into the stomachs of those who bought their beefsteaks from the big packing companies.

Proletarians had never cared much about the investigation anyway. They are always too busy trying to get the money to pay the butcher to stop for other matters, But the dirt and the nauseating stench in packingtown disappeared. White caps and aprons are now furnished employees in departments where visitors are invited when they go to see the wonders of the great packing house district. The beef trust needed the investigation badly. And the immunity bath saved them from further losses.

The stage is now set for another comedy. The Beef Trust is to be tried again. Financiers declare that Morgan and Loeb, the backers of the Trust, will not permit the emasculation of the combine. The Army and Navy Department of Great Britain has discovered that if the courts decide against the Beef Trust, the packing companies will probably be unable to supply the meat required by these departments, which have been entirely supplied for some years with the American product. A war might break out and the soldiers be unable to get any of Armour’s canned beef. So the British War Department has refused to renew its contract with the Beef Trust. And the packing combine lost the privilege of supplying the meat for the British Army and Navy. A large order gone to pot!

The ruin of the industry is again threatened. The packing companies are running on about one-fifth time and Trust Buster Taft may find that he has to come to the rescue. It is good politics to play a little comedy for the benefit of the working class. But it is not good politics to injure your own friends.

However, this trial and its consequent disclosures supply valuable object lessons to the student of political economy. The development of the packing industry is closely related to certain scientific discoveries of the last thirty years. These discoveries are in turn the results of the pressing need of modernized methods of production caused by the expansion of markets in all directions.

So long as the consumption of meat and meat products, except smoked and pickled goods, was immediate, the industry had to be confined to localities where meat was needed. The master butchers of yore bought their live stock, killed, dressed and sold the meats and products in the local markets from day to day. Except ham and smoked sausage there was. no production in excess of the demand. The highest number of men employed by one master in big industrial centers was perhaps fifty men. In small towns from two to three journeymen helped the masters. All employees were skilled men and proficient craftsmen, acquainted with every detail of the work. Today the largest employer in the meat packing industry in a city like Berlin, Germany, where all live stock must be killed in communal slaughter houses, requires only fifty-six men. Compare such a plant with the plants of Swift & Company and the Armour Packing Company which employ respectively 26,000 and 38,000 men and women.

Cattle and hog raisers in the United States ship the surplus supply of live stock that cannot be used in local markets, to England, France and Germany. In the latter country the hog barons ‘“junkers” used their power in legislative bodies to secure laws especially designed to keep out all imported live stock from the markets. They succeeded to some extent in thus keeping up the prices on their own live stock. The law of supply and demand was temporarily neutralized.

The killing of live stock, the dressing and selling of meat products in those days had to be done within a week’s time, and it took nearly as long to run a hog, or a lot of cattle or sheep through the various processes before they were finally ready for the market.

The invention of artificial ice-making and cooling by Prof. Lind and of meat preservation by Prof. Liebeck gave the signal for a revolution in the meat packing industry. Meat could now be dressed, thrown into the coolers and shipped in refrigerator cars without danger of deterioration. It was sent to larger markets, distributing points also equipped with ice machines or to seaports where steamers containing cooling rooms could take the dressed meat to all corners of the globe. The conserving process suggested the packing of prepared meat into cans. Thus safeguarded against deterioration, caused by exposure to the open air, the goods can now be kept and preserved for weeks or months, and they have been known to be kept for years and then consumed.

Production for a larger market and for the export trade could only develop in cities centrally located, within easy reach of all rural districts, so that livestock could be shipped to the market with dispatch.

Cincinnati was the first pork-packing center, but the growth of Chicago as the largest railroad and lake shipping city of the world has made it the logical center of the international packing industry.

With the increase in the size of packing plants there came a subdivision of the labor process on an ever larger scale. New and ever larger labor-saving machines were installed.

The moving benches, lately introduced, displaced almost the last skilled worker from the yards. Where formerly a butcher workman had to be a skilled and proficient mechanic and know every detail of his trade, he is now reduced to a mere link in the long chain of laborers required in the never interrupted process of preparing meat for market.

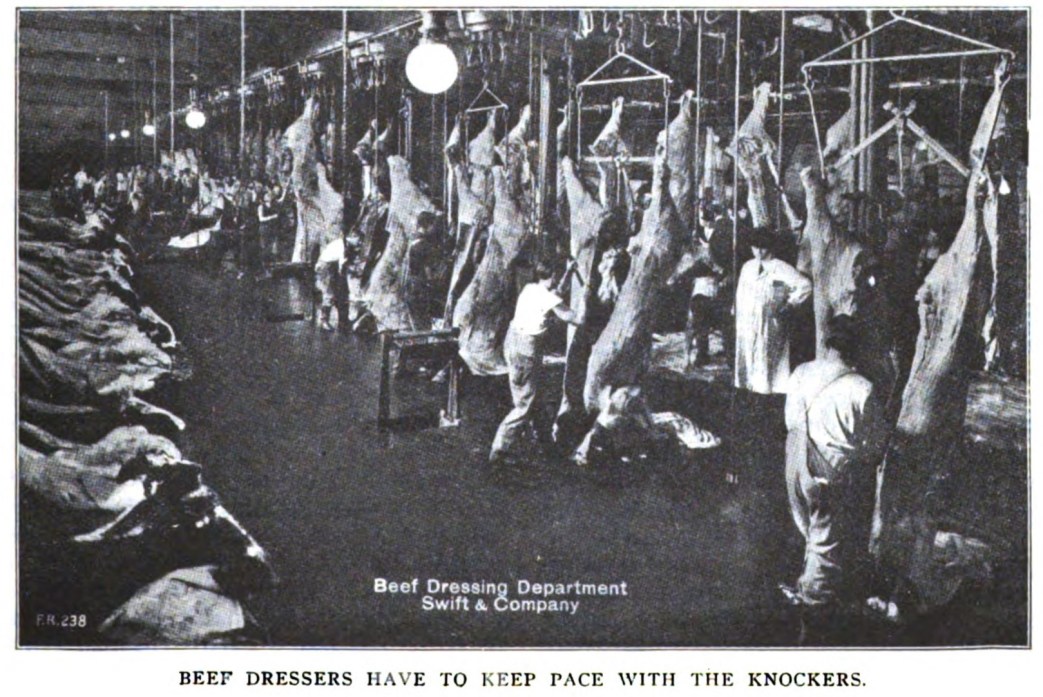

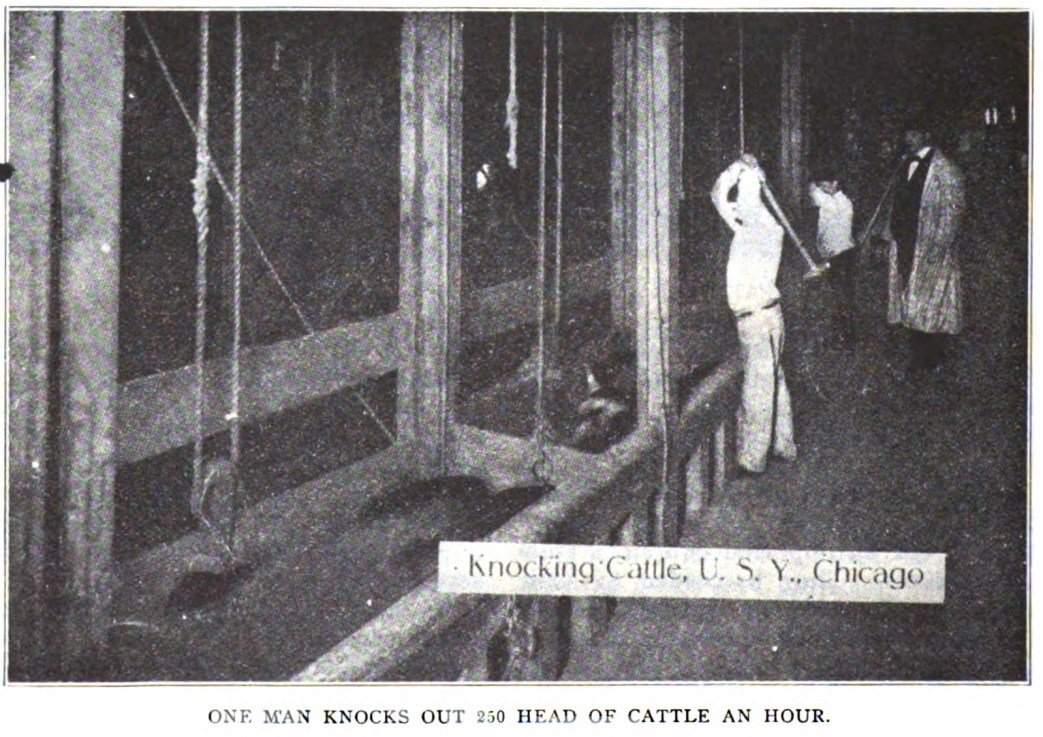

Forty-six operations, again subdivided into over 120 hand operations, are required, for example, in the beef-killing department. The man who stuns the cattle with the huge iron hammer is compelled to knock down 250 head in one hour, the men cutting the throats performing and the other operations are obliged to keep the pace set by the “knocker.”

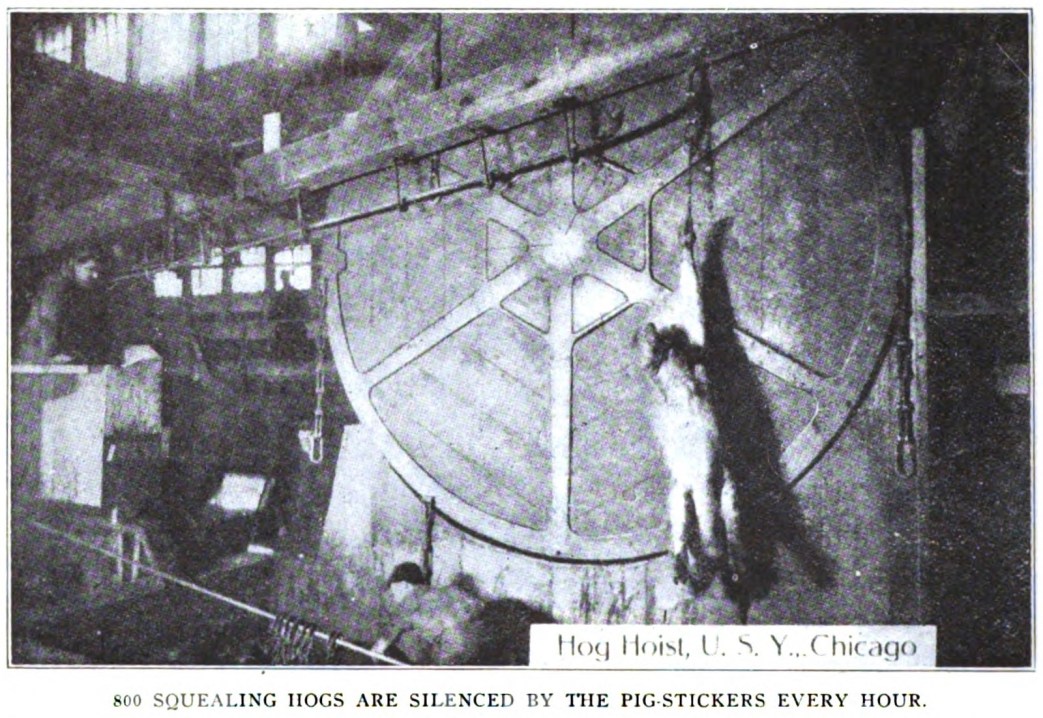

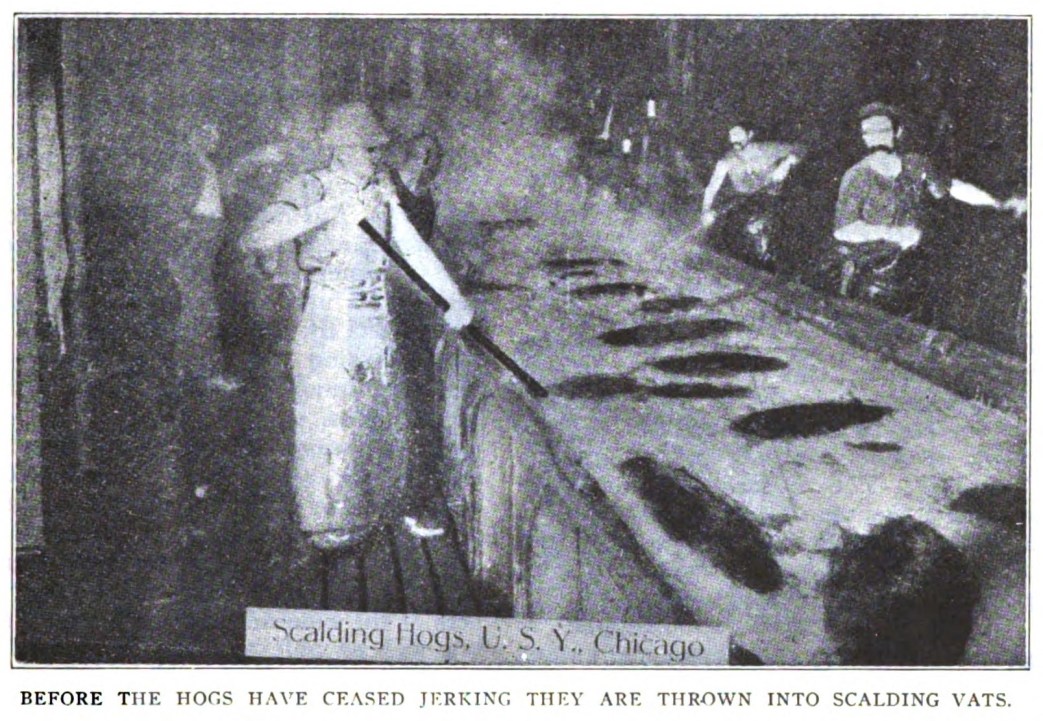

In the hog-killing department twenty-eight operations are performed by 120 workers to get the porker into the next department, where the animals are cut up and the various parts automatically passed on to the respective departments to be turned into different brands of meat products.

Squealing and kicking, a hog is jerked into mid-air by an automatic wheel bearing a chain attachment that hauls up the next porker. The pig-sticker is compelled to stop the screams of 800 hogs in one hour. With equal rapidity other functions are performed.

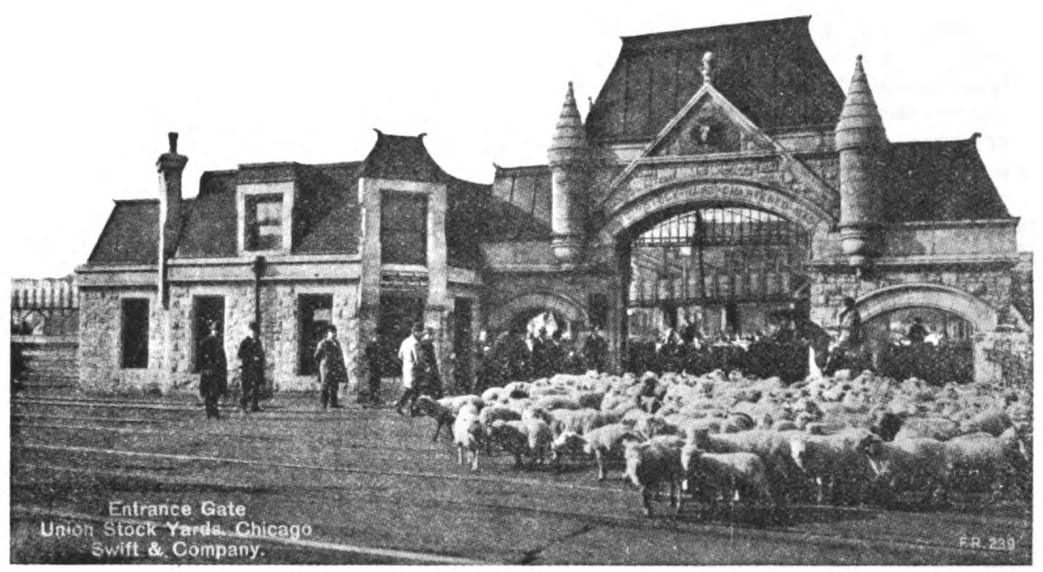

The small master butcher is allowed to exist only in the role of distributer and agent of the Trust. He is absolutely dependent upon the supply of beef and pork that the Beef Trust allows him. When here and there, apparently independent packers are allowed to get supplies of livestock, they usually have to depend on the stock-raising farmer of the immediate vicinity. Often they have to be satisfied with the livestock left and not sold in the Stock Yards in the over shipped into the Chicago Stock Yards big packing centers. On an average 850 loaded cars are every day the year round and about 60,000 head of livestock are killed and transformed into meat products every day.

Over 900 cars, packed with meat products, leave the terminals at the Stock Yards daily to supply meat in many far nooks and corners of the globe.

Much could be written of the wonderful mechanical appliances installed, by which the cost of production, the labor power cost, is brought to the lowest possible point.

So rapidly are the various operations performed that within one hour and a half after a live animal enters the slaughtering pens the meat is dressed and ready for the “chilling” process in the great coolers.

How the Beef Trust manufactures its own tin cans, builds its own: refrigerator cars, established its own printing plant and daily paper (The Drovers’ Journal), the story of its ice manufacturing plant, how the entire industry is a community in itself, containing more workers and their dependents than the state of Nevada possesses population, it would take a whole volume to tell. But in these days of scientific production everything is saved. Odds and ends are worked up into soap, glue, grease, fertilizer, collar buttons, combs and other useful commodities.

The grease is no longer skimmed from the ill-smelling Bubbly Creek described by Sinclair. The water is run through a new sort of a separator and screen that combs out every particle of grease and bone. Not one ounce of hoof that goes into the packing houses is wasted, as might be guessed, since the output of cars daily is many carloads bigger than the intake.

As a huge mechanical instrument of production, the packing industry has reached a stage of perfection almost unequaled in any other field.

But the tens of thousands of workers in the packing industry have little to say concerning the conduct of this modern industrial state of which they are so important a part. They have no vote in the administration of affairs in this industrial commonwealth. But one time, some years ago, they. established certain rights and used them to say a word and more as to the disposal of their labor power.

The Knights of Labor were the first to wake them up. In 1885 they won the eight-hour day for everybody in the packing industry and without a strike. It was virtually the first industry in which the workers had gained such a revolutionizing point. Over 2,500 more employes were added to the pay roll as a result of the curtailment of competition among workers for jobs and wages went up. Common laborers were able to demand 22 cents an hour, while many “skilled” workers today have to be content with 16 or 17 cents an hour.

The packing house workers only enjoyed this prosperity for six months. Agents of the company were made officers of the assemblies of the workers, or officers of the workers’ assemblies became agents of the company. The employers took away all the concessions that had been granted. The employes went on strike. Governor Oglesby called for the militia to cow the men. But they did not return to work. Just as the strike was practically won, General Master Powderly of the K. of L. issued the peremptory order for the strikers to return to work. The trial against Spies, Parsons and their associates was in full swing. The newspapers howled against strikers and called them “direct actionists.” Master Powderly did not wish to be identified with so unpopular a cause, and for this reason the strike was called off. Over 4,000 workers found themselves without jobs.

Thereafter new machines rapidly displaced human labor power, and the skilled workers gradually disappeared. Women and even children began to work in the meat-packing plants. The North Germans, Irish and Bohemians, who formerly predominated, were slowly supplanted by workers from Austria-Hungary, Lithuania and Slavonia. Wages were slaughtered, too, and the conditions became appalling. A spirit of revolt arose. The teamsters in the yards first struck in 1902 and, supported by their comrades, they won the strike. Other strikes followed, and the packing companies were unable to check the flood toward organization. So they set their agents to work again to divide the workers on other issues.

Fifty-six crafts had to organize into as many craft unions. One was used to defeat the other. The engineers and firemen, for example, both organized in separate craft organizations, were cheated out of an eight-hour day by a board of arbitration composed of clergymen. The form of organization precluded any concerted move.

Later revolt broke out anew. A portion of the workers went out on strike, while others remained at work. All lost in the long run. Organization was completely wiped out.

But the agitation had taken deep root. The hope of the toilers centered now on the political field. They turned toward the Socialist Party. They hoped for reforms through political action. Two socialist representatives, Olsen and Ambrose, were elected into the legislature of Illinois in 1904. But they were not the type of men to “stay in.”

Meanwhile the sales of beef products had decreased enormously, partly as a result of Sinclair’s exposures in “The Jungle. They packing plants only wanted a few men for two or three days a week. All the nerve was taken out of everybody. The labor movement temporarily died in Packingtown.

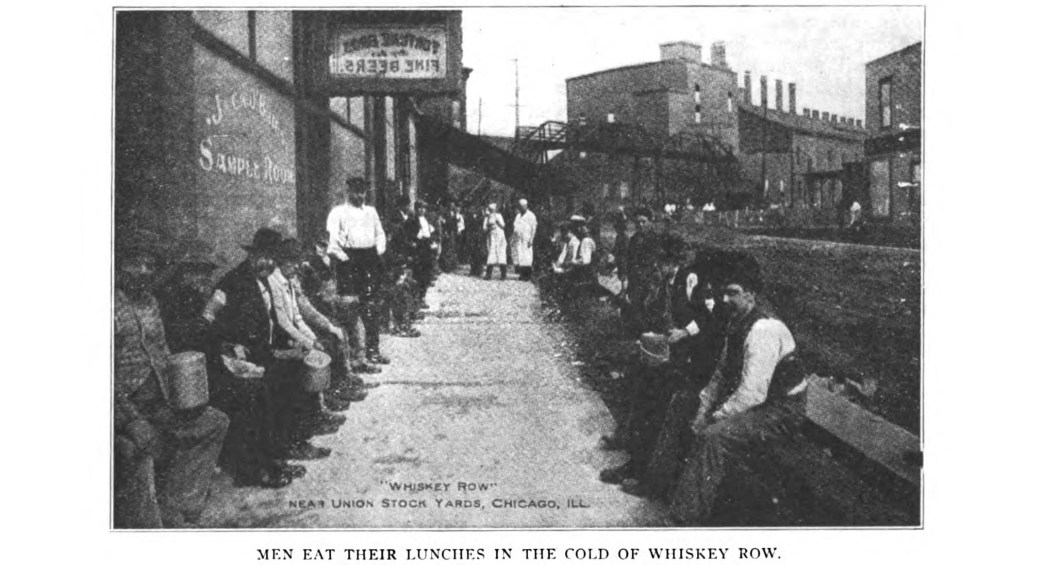

Today Packingtown is wrapped in gloom. Working conditions are almost as bad as they can be. The speeding up of the machines, the introduction of more labor-saving implements, have increased the productivity of the worker about 30 per cent as against 1905. Wages are cut right and left. So appalling is the misery “back of the yards” that reformers and settlement workers despair of ever accomplishing anything there. Their resources do not go far enough to do much in the way of ameliorating conditions. The packers always welcome the charity or settlement workers. Such people keep the workers from the acts of desperation that are the result of hopelessness.

The Socialists will regain the Packingtown districts. They must do it. They can do it. But they must show the workers, thousands of whom are already hearing this message, that charity and reliance will not bring relief. And they must show them how to fight on the job by organizing into One Big Union, the industrial union embracing every worker in the Yards.

The message of One Big Union has been heard in the Stock Yards of Chicago, Kansas City, Omaha and other places. And thousands are eager for the new unionism. The toilers have started to get together. Neither charity nor the acts of the kind-hearted settlement workers will be able to long delay the day when the organized working class will put the Beef Trust on Trial—not to dissolve the Octopus, not to smash the institution, not separate the wonderful apparatus of production into component, disconnected parts, but to redeem to the workers the wealth they alone created and to bring happiness and blessings to the workers of Packingtown the happiness that all the workers the world over will enjoy.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n09-mar-1912-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf