Essential history of the founding of I.L.G.W.U. Local 2 and the uprising of largely immigrant women clothing workers from a central figure in those events.

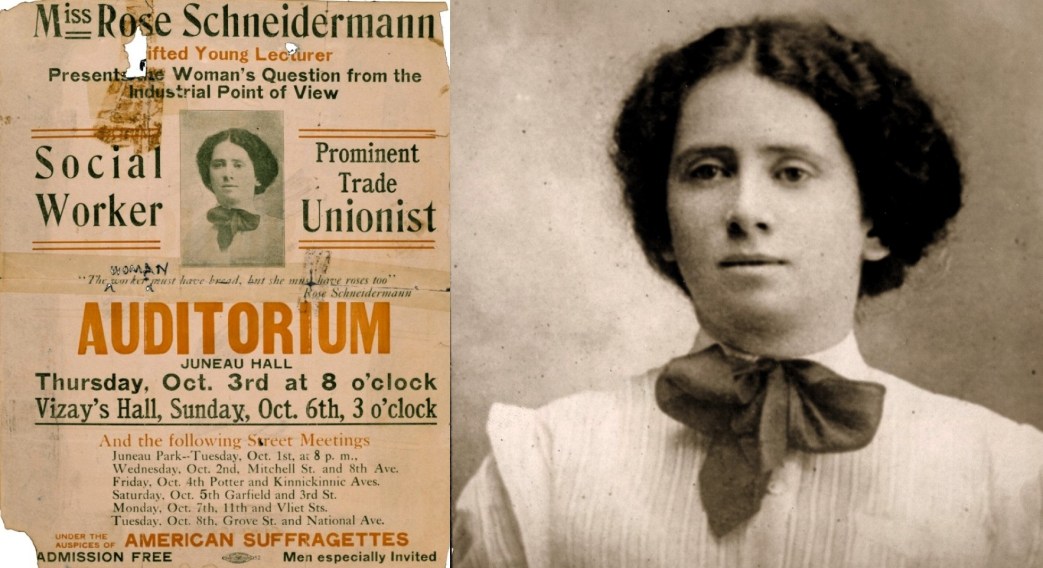

‘The White Goods Workers of New York and Their Struggle for Human Conditions’ by Rose Schneidermann from Life and Labor (W.T.U.L.). Vol. 3 No. 5. May, 1913.

Ten o’clock, the 9th of January, seven thousand white goods workers, contrary to the prediction of the wise, walked out of their shops and tied up the industry in New York. At ten o’clock, February 20, seven thousand white goods workers. returned to their shops, again contrary to the wise, victorious.

Within five short weeks the white goods trade in New York had been converted from a disorganized trade into an organized trade, for the employers as well as the workers had come together and the competition among the manufacturers as well as the competition among the individual workers was replaced by conferences and cooperation. While this great transformation was brought about within so brief a time the real work, the hard work and the work which required faith and determination, had been done before.

About eight years ago there was an organization of white goods workers. At one time it included eight hundred members. It was independent of the local labor movement or the national organization of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers. The panic of 1907 put that little independent union out of business, which had held together a year and a half.

The present union, which now numbers seven thousand members, had its real start four years ago. A small shop on the East Side struck against a wage decrease and the strikers came to the Women’s Trade Union League for help. I met with the striking shop and within a few days they went back victorious–that is, they prevented a cut in wages. The following week I met with this small group and told them they were not safe against reduction; that they could never hope for increases unless they formed a permanent union. This was in the early spring of 1908, and from that time on the League held small meetings, large meetings, street meetings, mass meetings and every sort of a meeting. It held its street meetings around white goods shops at six o’clock in the evening, as the girls were leaving work. This agitation was interrupted when I was called to help in the great strike of the waist makers in the fall of 1909.

For several months the little union held together as best it could. In the spring of 1909 I told the girls it was impossible for them to hold a union independent of the great labor movement, that they needed the backing, and they owed it to their brothers and sisters to be a part of the greater labor movement.

In March, 1909, our union was chartered by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union as Local 2. We continued our propaganda work. Every little while there would be a shop strike–that is, a strike in a shop which was not connected with the union. The strikers would meet at the League and we would put forth our best efforts to secure the demands of the strikers. Many times the strikers would go back to work and forget what the union had done for them. For many, many months the membership would vary, sometimes it would fall as low as 25 members; sometimes there would be 150 members paying dues, and sometimes as many as 300.

But the great shirt waist strike had had its effect on the white goods trade. Without exception the girls would say, “We never can organize our trade until we do what the shirt waist makers did. We must have a general strike, we must bring the girls all out together. We must do this if we ever intend to have a big union.” For four years this was the persistent demand of the girls who were faithful to the union, and even the demand of the girls who came in as casual members. The casual member would excuse herself on the ground that it was useless unless the others would come. She met constant opposition in her shop and would hear from the other girls, who had never been to the union, “It’s no use our joining unless every one joins.”

In the spring of 1911 I was delegated by the union to go before the General Executive Board of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers in New York and lay before them the demand of the local for money which would pay the salary of an organizer. Our little local knew that the General Board was in a prosperous condition, owing to the general strike not only of the waist makers, but of the cloak makers. We asked them to donate $500.00 to the salary of an organizer for the White Goods Workers’ Union, as well as the petticoat makers. For several months negotiations were carried on between the white goods workers and the petticoat makers considering the amalgamation into one union. The petti-coat makers were jealous of their own identity and refused to amalgamate. Later the petticoat workers disbanded. The organizer which we asked of the General Board was granted.

From time to time agitation among the union members was taken up and pushed. Leaflets were printed and bulletins issued and shop meetings were called more frequently than heretofore. In June, 1911, a Cooper Union mass meeting was arranged. This meeting was called to discuss the advisability of a general strike. The circulars did not announce that a general strike would be called. It is my opinion that it was this indecision on the part of the union at that time that made the meeting not altogether successful. There were nearly fourteen hundred present and a number of members joined.

The union had not yet secured the consent of the International for a general strike. The International was at this time involved in the great Cleveland strike and its money and strength were being sapped. As the Cleveland strike continued, the postponement of the strike of the white goods workers became inevitable. The girls felt that its officers and leaders had not kept faith. They were so eager for the strike in their own trade that they could not believe that any situation whatever would prevent the International from entering on a general strike if the case were put up to them in all its urgency. The membership declined. The year 1912 opened with the union in a critical condition and there was no money. The union then sent representatives to the International and asked them to pay the salary of an organizer for two months, the money which was donated towards the salary of the organizer had gone long ago. The committee assured the national president that they could do some strong organization work and that it would be possible to organize two of the largest shops in the city. The president declared that it was impossible to grant their request. He said, “The union must prove to the International that it has more life and determination than it has heretofore. Before the International can pay an organizer the union members must show their power to organize themselves.” It was at this time. that Brother Elstein of the International and I went to the Strike Council of the Women’s Trade Union League and asked permission of the Council for a full month of my time to be devoted exclusively to the white goods workers. The Council granted the request and the confidence of the members of the union was restored and new enthusiasm resulted.

In December, 1911, Brother Elstein and I succeeded in organizing two factories which included two hundred girls. In organizing these two factories we secured a reduction of hours from 60 to 50; abolition of fines of 40 cents per week for electric power and an increase from 50 cents to $1.00 a week for week workers, and an increase of 12 cents on some garments for piece workers. These new conditions were secured without a contract with the union. The addition of this new membership gave the union the financial assistance it needed and it was possible to engage its own organizer.

In June, 1912, the International held its national convention, and at this convention Celia Kaufman, a member of the union, made the memorable appeal which won the support of the delegates for a general strike. The union, with its new organizer, was able to release me for several months for the suffrage campaign in Ohio.

In October I again took up the work under the Strike Council of the Women’s Trade Union League and from that time on the organization increased at a rapid rate. While the Strike Council hoped that we might strengthen the organization so that we could secure the demands of the white goods workers without a general strike, it was evident to me and to the members of the union that a general strike was inevitable. Realizing this I began in November to lay plans for the strike. I asked a number of the members of the Women’s Trade Union League if they would contribute to a guarantee fund if the strike was called. I had very little response. It is evident from the generous donations made later that appeals for a strike fund are more successful when people are confronted with the actual suffering and conditions of the workers.

I organized from the League membership a committee to distribute circulars the morning of the strike and to instruct each shop as to the hall assigned it and the hour to quit work. There was a committee of League members to take charge of the halls, a Speakers’ Committee and a Publicity Committee arranged for. On January 6, 1913, a meeting was called at Cooper Union of all white goods workers to vote on the question of a general strike. Cooper Union was filled to overflowing, and Labor Temple had to be taken. The vote for the strike was unanimous. At seven o’clock on the morning of January 9 the girls of the union and every member of the League who promised cooperation were on hand. Members were stationed in the halls to receive the strikers; others were stationed at the shops to notify the strikers where to go. By noon that day everyone knew that the strike was a success. The afternoon of the second day reports from the hall chairman were filed with the International, showing that seven thousand girls had answered the call. The enthusiasm was tremendous. The American girls as well as the Jewish and Italian girls caught the spirit of the union and were ready, as it proved in the next five weeks, to stick to it through life or death if they should be required. The second day of the strike the International decided that they preferred to furnish the speakers and carry on the publicity work. The members of the League who had been given these tasks and were in good shape for carrying them out immediately turned their time and effort into other channels of cooperation.

The strike was only two weeks old when I was called away from the field work to sit in conference with the Manufacturers’ Association. It was evident from the first that they would fight the question of a union shop, as well as object to the protocol agreement which the cloak makers and shirt makers had secured. The demands which were laid before them were: A fifty hour week; double pay for overtime work; abolition of the tenement house labor; three legal holidays with pay; abolition of payment for power and thread; increase in wages of 10 per cent for piece workers and $1.00 a week for week workers; no girls to receive less than $5.00 a week (some of the workers before the strike had been paid as low as $3.00); weekly payments instead of fort in ten days the manufacturers consented nightly.

The manufacturers were willing to grant these demands; they granted even the establishment of wages and grievance boards on which an equal number of the members of the manufacturers and the union would be represented; they granted a shop price committee, but they stood out against recognition of the union in the shop or the preference to union members. As a compromise we secured at last the following clause: “The Manufacturers’ Association believing in the principle of collective bargaining, believe that those who share the benefits of the union should share in its burdens.” We therefore decided to recommend the acceptance of the agreement to the strikers, because we knew we had to save the organization and could probably interpret it to mean that the manufacturers would take the position that all of their workers should join the union. As the negotiations with the manufacturers had leaked out it was decided that it would be better to refer the agreement to the strikers. It was first presented to the Strike Committee, which was composed of the old members of the union, then to a meeting of the shop chairmen and two days later to the strikers themselves. The manufacturers found during these three days when the agreement was being presented to the workers that they, the strikers, were loath to accept less than an unqualified assurance of the association that they contract to employ union members or that they preferred union workers and that all strikers should be reinstated. Fearing the vote would go against the acceptance of the agreement the manufacturers wrote two letters, which were presented to the strikers the day of voting. One promised the reinstatement of all the workers to their former places, the other the recognition of the union in very definite terms. The workers questioned whether, after the strike was over, the letters would be a part of the agreement signed by the association on Tuesday, February 11. The vote on the agreement was turned down three to one. There was the most enthusiastic rejoicing in every hall. Never has there been a greater mass expression.

Negotiations for two or three days were broken off with the manufacturers. Within ten days the manufacturers constented to embodying the letter in the agreement. When the announcement was made to the strikers that the manufacturers had granted this compromise the joy of the strikers was complete.

Every ally who had helped in this five weeks of strike and had stood by the workers through their suffering was rewarded by the spirit of good fellowship which was shown. Everybody who had helped was presented with a token of the strikers’ appreciation. Everyone regretted, in spite of the joy over the settlement of the strike, that a break had come in the relationship which had grown up between the strikers and their friends. Those in charge of the halls said: “We must not lose contact with the girls. We must arrange in some way or other to continue our friendships.” While the association of the strikers in the halls was intimate it was the association on the picket line which made the lasting friendships.

“We never, never before” we heard constantly, “have seen such girls; we have never known such a spirit.” The girls started off on their picket work in the morning in many cases without food; the luncheons served at the various halls of coffee and sandwiches, and in some cases fruit, was the most substantial meal of the day. Hungry and cold they went on their picket duty like soldiers and gradually lost all fear of thugs and policemen. The scabs in the white goods trade must have had an unhappy time during these five weeks. Every night there were unwarranted arrests of many strikers. The magistrates continually accepted the word of the policeman against the word of the striker. Those who stood around the door of Jefferson Market Court would hear every night expressions of indignation from the girls who had been fined $2.00, $3.00, $5.00 and $10.00 for doing nothing. The girls who had done “something” were without exception ready to take the consequences, but the sort of justice meted out by the court which fined a girl $10.00 who had simply walked up and down on her picket duty was too much for these high spirited girls.

Those in charge of the halls were Maud Younger, Mollie Best, Mrs. Beals, Mrs. Jessie H. Childs, Louise Smith, Mrs. Cothen, Violet Pike and Mrs. J.H. Wise. Mrs. Elliot furnished entertainment for the various halls and had charge of the speakers’ bureau until it was taken over by the National. A large number of members of the Women’s Trade Union League helped in the halls and on the picket line. Seven thousand dollars came into the League for the strikers, four thousand of which was unsolicited. This came from a large number of people who had become interested in the strike through its publicity and through helping on the picket line and in the courts.

Miss Younger, who had taken charge of Labor Temple, kept a record of the cases of false arrest. She, with Helen Marot, She, with Helen Marot, took ten cases before the Commissioner of Police, who referred them to Inspector Schmittberger. A hearing was held and three out of five cases were upheld, the officers either being reprimanded or held for trial. What surprised everybody in the hearing was the clear statements of the strikers and their marvelous ability as witnesses. In one case four girls charged that officer 1812 was called by the District Inspector to take a scab home; they followed the officer and the girl for several blocks, when the officer turned on the pickets, drawing his revolver and pointing it said: “If you follow any further I will shoot you. The pickets had no idea whether he would carry out his threat or not, but they knew that their part in the fight was courage and they followed the girl and the officer to a house on 10th street, which we afterwards found out was a disorderly house. As the strikers told the story to the Inspector he asked many questions. Among them he said: “Describe the revolver.” They did not know the names of the parts of the revolver, but all of them said, either: “It was a dull grey or gun metal.” The Inspector who questioned the three girls, drawing from his drawer a nickel plated revolver, asked if it looked like that. The girls on the stand and three others off the stand at once answered, “No not like that, that’s bright–the one he carried was a dull one.” The officer was called to the stand and disclaimed having told the girls he would shoot them. The Inspector asked him to show his revolver. It was a tense moment while the officer was pulling the revolver from his coat. When it appeared it was as the girls had described it, a dull grey or gun metal.

How little justice we can expect in New York on picket line from the police or magistrates is told in a number of cases. One case Mr. Leon, a well known New York lawyer, was interested in and gave his especial attention. A girl striker had undertaken to follow home a strike breaker, and had boarded a car. She was pushed off the car while it was in motion and fell on her back. She was severely injured. A warrant was secured for the arrest of the officer who had caused her fall, although the case had been, taken to a higher court the officer was discharged. Able witnesses testified in favor of the girl.

The League is now taking twenty-five cases of false arrest before the Curran Committee. All of the seven thousand white goods workers in New York are saying, “There’s no justice in the courts for us. We must make our fight as best we can.” They have proved that if they stand firm they can beat the manufacturers. They have still to learn that if they stand firm they can beat the courts and help bring about a day when women arrested in the night court will not be heard saying, “I did not know, judge, that he was an officer of the law with more rights than me nor anybody.” Nor again will a magistrate fine a girl for saying, “This is a free country,” while walking peacefully by a shop, and on the officer’s testimony declare, “The freedom of this country, young lady, will cost you $3.00.”

Life and Labor was the monthly journal of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was founded by the American Federation of Labor, which it had a contentious relationship with, in 1903. Founded to encourage women to join the A.F. of L. and for the A.F. of L. to take organizing women seriously, along with labor and workplace issues, the WTUL was also instrumental in creating whatever alliance existed between the labor and suffrage movements. Begun near the peak of the WTUL’s influence in 1911, Life and Labor’s first editor was Alice Henry (1857-1943), an Australian-born feminist, journalist, and labor activists who emigrated to the United States in 1906 and became office secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago. She later served as the WTUL’s field organizer and director of the education. Henry’s editorship was followed by Stella M. Franklin in 1915, Amy W. Fields in in 1916, and Margaret D. Robins until the closing of the journal in 1921. While never abandoning its early strike support and union organizing, the WTUL increasingly focused on regulation of workplaces and reform of labor law. The League’s close relationship with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America makes ‘Life and Labor’ the essential publication for students of that union, as well as for those interest in labor legislation, garment workers, suffrage, early 20th century immigrant workers, women workers, and many more topics covered and advocated by ‘Life and Labor.’