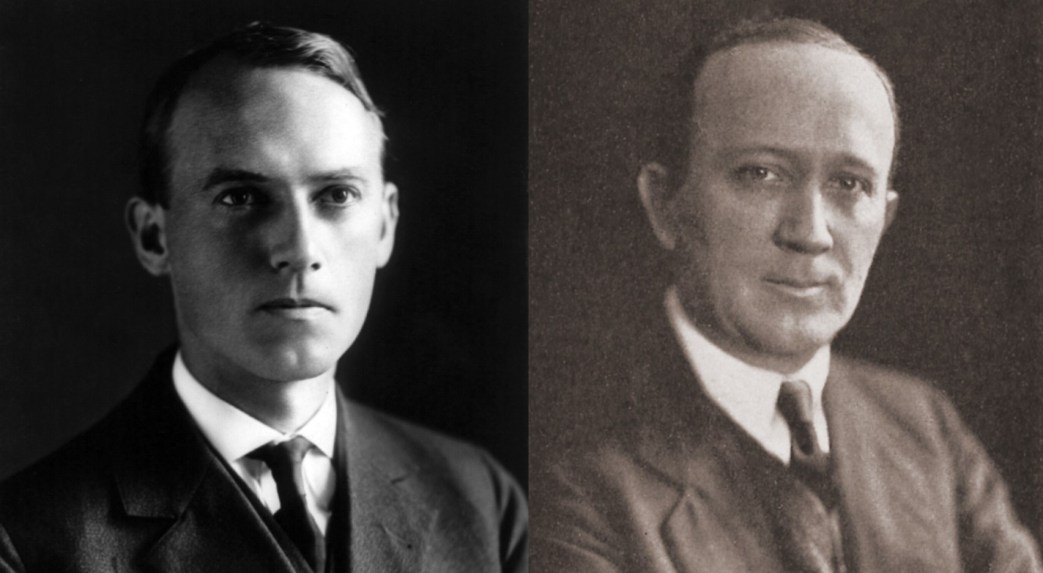

One of the best exchanges for understanding positions and politics in the 1920s Communist movement must be Scott Nearing’s 1924 ‘Open Letter’ and William Z. Foster’s lengthy response (coming soon). Centered on differing estimations of the militancy and consciousness of the U.S. working class, with two very different conclusions on the way forward, Nearing then stood outside the Party and its debates, making this exchange less factional than most.

‘Scott Nearing on Party Policy: An Open Letter to William Z. Foster’ from The Daily Worker. Vol. 2 No. 46. May 10, 1924.

Dear Comrade Foster:

You have asked me to state my position regarding the policies of the Trade Union Educational League, and I am very glad to have an opportunity to do so, because I am convinced that the tactics followed by the left wing of the Ameri- can labor movement during the next few years will have an important effect on the future of the class struggle in the United States.

• • • • •

Your article in the November Liberator entitled “The AF of L Convention”; your article in the January Labor Herald called “An Open Letter to John Fitzpatrick”; and your “Industrial Report” to the Workers Party convention all are based on certain assumptions which I would summarize as follows:

1. That the decision of the Portland convention to expel Dunne, and the refusal of the convention to endorse a labor party and to endorse Russian recognition represented the sentiment of the labor autocracy and not the sentiment of the rank and file;

2. That the rank and file would have acted differently had they had an opportunity to register their opinions on these issues;

3. That there is a revolutionary ferment among the masses of American workers.

• • • • •

On the basis of these assumptions, how would you explain certain outstanding events in the American labor movement during the past few years? Such events as:

1. The presence of Tom Mooney in jail after it has been demonstrated and asserted by representatives of the Federal Government that he was convicted on faked testimony, and after the repeated protests of the more progressive groups in the American labor movement?

2. The presence of Sacco and Vanzetti in a Massachusetts jail under circumstances almost as disgraceful to American labor as those surrounding Mooney’s continued imprisonment?

3. The indictment, prosecution, and conviction of members of the Workers Party in Western Pennsylvania; of members of the IWW in California; of members of the UMW of A in West Virginia; of the Michigan Communists? The latest reports show 114 political prisoners in state prisons, “serving sentences solely for the expression of opinion or for membership in radical organizations.”

4. The discrediting of Alex Howatt in the national convention of the United Mine Workers; the overwhelming defeat of the TUEL policies in the conventions at Scranton and Decatur, after the questions had been threshed out in the local unions?

5. The ease with which the Pressmen’s Union, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, and other organizations have been able to throw out the left wing elements without any consider- able protests from the membership at large?

6. The very heavy losses to the membership of such unions as the machinists, in which there had been no considerable internal friction?

7. The apathy and indifference with which the rank and file of America workers have regarded the “open shop” drive; their eagerness to be 100 Percenters along with Judge Gary and John Rockefeller, and their unwillingness to make a stand against the exploitation and imperialism in which the American rulers are so deeply involved?

• • • • •

While I do not for a moment pretend that I know the answers to all of these questions, I should like to present an explanation which I think fits many of them. My assumptions concerning the present situation in the United States are quite different from yours. Let me begin my answer to these questions by stating the situation in the United States as I see it.

1. There is no parallel anywhere in modern labor history to the present situation in the United States, because in no other country (with the possible exception of Germany during the war) was a large and important labor movement so completely taken into camp by the opposition as the American labor movement has been taken into camp by the Chambers of Commerce.

(a) This has been done, first of all, by getting hold of the labor leaders—giving them tips on the stock market; offering them government jobs; “getting together” with them in various community activities; giving them important posts inside the political organizations of the two old parties.

(b) It has been done, in the second place, by lining up the rank and file throughout the most complete system of propaganda, lies, diversions, amusements, excitements, and thrills that the world has ever produced. The whole machinery of education is in the hands of the business interests and they do not hesitate to use the newspaper or the movie to put their interpretation on events, to suppress information, or to deliberately misrepresent the facts. Take Russia as an instance; or take the IWW. They have been shamelessly and deliberately lied about until the rank and file of the American workers and farmers have come to believe what they are told.

(c) It is for this reason that the rank and file of the AF of L would have supported their representatives in the Portland convention. In fact, I am of the opinion that if there were any way to measure the situation exactly, Gompers would be found on the left, and not on the right of the AFL rank and file. I am well aware that this is not the accepted opinion of the left, but I am basing the judgment on a very considerable contact with members of the organization.

(d) If I am at all correct in this assumption, it will go far toward explaining the apparent apathy in the American labor movement—it is not apathy at all, but tacit consent. Remember that most American workers have gone to the public school; that they read the papers and magazines published almost exclusively by big business interests; that they quite generally belong to the churches; and that they almost universally vote the old party tickets. (In the last Presidential election 96 percent of the total vote was cast for Harding and Cox, and 4 percent for Debs and Christianson)

(e) According to this interpretation, not only the officials of the unions, but also the rank and file are committed to the present economic order. They believe in it, and in any crisis they will support it.

2. Does this mean that there is no revolutionary sentiment in the United States? Not at all. It does mean, however, that it is not typically American. The native born American who believes in fundamental change is the exception and not the rule.

(a) American opinion is still found on the life of the village and on the farm. Even those who have moved into the cities have hopes that someday they will be able to own a little place in the country and retire to it.

(b) The migratory workers have pretty well given up the idea, and they constitute the largest single revolutionary nucleus in the United States today. Unfortunately, however, the very nature of their work makes it trebly difficult to organize them, and the 40,000 members reported by the IWW probably does not represent more than 2 or 3 percent of the total number of migratory workers.

(c) The average skilled craftsman still looks forward to home ownership under the present system. He even believes that if he does not succeed in getting out of the ranks of labor, his son may, so he sends him off to college, and trains his daughter to teach school.

(d) The revolutionary sentiment in the United States is strong among certain foreign-born workers—particularly among those of Slavic origin, who have been most emotionally aroused by events in Russia. The new immigration laws will be so adjusted, however, that the supply of these North Europeans will be heavily cut down, and those that are admitted will be watched with hawk-like care.

(e) Revolutionary sentiment is strong in certain districts, such as Butte, Seattle, and in parts of New York and Chicago. In most of these cases, however, the strength is in the foreign-born districts, and the sons and daughters of such foreign-born revolutionists usually become ultra-respectable American patriots.

(f) Revolutionary sentiment is strong in certain needle trades, railroads, machinists’ and miners’ locals. Again, however, it centers in the Slavic and other foreign-born elements.

(g) I am assuming, as you see, that there is no considerable revolutionary sentiment among the masses of American born workers and farmers. I realize that they are discontented, but they assume that “times will pick up” under the present system. There are, of course, many exceptions—readers and thinkers who have kept up with the world and who have not been fooled by the propaganda. But they are relatively few. In my judgment, whatever revolutionary sentiment there is in the country today cannot be described as in any sense “American mass-sentiment.”

• • • • •

3. Those of us who believe that there must be radical changes in the economic and social life of the United States therefore find ourselves in a position where the radical sentiment must be created. Hence our task involves first, education and second, organization, third, activity. I believe the farmers of the United States are as much in need of economic education as were the workers and farmers of Russia when Lenin began his work with them around 1885.

This line of argument, as you see, places us in quite opposite camps when it comes to the tactics that should be pursued. Let us suppose, first of all, that you are right in your assumptions. In that case:

1. The sentiment is here. All that is needed is an organization that will take possession of it. The line of procedure is not from education, through organization to action; but from organization, direct to action.

2. This organization can be spread very rapidly; can be mobilized quickly; and can strike, almost immediately, for specific results.

3. The American revolutionary movement should therefore extend its front with the idea of gaining immediate and practical successes, among which might be named the splitting of the old parties at the coming election (say by the nomination of LaFollette); the winning of the labor movement to the revolutionary program; and the establishment of a very large and effective political organization representing both the farmers and the workers.

4. It was on that assumption that you proceeded with the organization of the 1919 Steel Strike. What happened? You answer: “We lost the big steel fight. This was a tremendous disaster; not only because it wrecked the steel unions, but, what was infinitely more important, it destroyed a much greater plan.” That is exactly the point! An organization cannot stand too many defeats. Napoleon marched only once into Russia, but that once was enough to wreck his fortunes. The radical movement in the United States, following your policies, is marching toward its Moscow. When your front is sufficiently extended, and you are well cut off from your reserves, the enemy will annihilate your, as they annihilated your Steel Strike Organization five years ago.

Now let us suppose that my assumptions concerning the American situation are correct. Then the revolutionary movement must:

1. Realize that its available clientele together is small, no thought of leadership of masses, and highly localized, and rendered in part ineffective by its foreign admixtures.

2. Aim to hold this clientele together at all hazards; to preserve its morale and efficiency; to train it in effective and cooperative activities; to teach it to trust itself; to try it and discipline it until it becomes a really effective working force; and during all of this time to avoid decisive struggle which will almost surely wreck the organization.

3. Husband the resources of the organization carefully; admit members only after long probation and after careful scrutiny; making each move with the idea that the struggle is being waged against immense odds in a hostile territory, and against skilled generalship.

4. Expand the organization and its work slowly; taking no step that will unnecessarily expose it to destruction; making no move that will enable the enemy to deal a crushing blow.

5. It is not “radical” to build rapidly. It is radical to build fundamentally, and it is fundamental building that the movement needs in the United States.

The most serious blunder of the radical movement in the United States during recent years is that it has assumed a following that does not exist. Consequently, you have tried to do, in a few months, what it will take years, and perhaps decades to accomplish. The radical movement has taken on the nature of a mass meeting, when the times call for a careful course of elementary, high school, and university training. Rome was not built in a night.

John Pepper writes in his labor party pamphlet as though he had behind him a trained, disciplined body of militants, 100,000 strong. At a pinch, he might rally 10,000, but I doubt whether he has 5,000 that he can rely upon.

The theses published in The Worker of Dec. 1, 1923 would be sound if the Workers Party had 250,000 militant and disciplined English-speaking American citizens upon whom it might de- pend to carry through the program. But The Worker for Jan. 12, 1924 reports the total membership of the Party as 15,233, of whom “at least 50 percent is an English-speaking membership.” If all of these members could be counted upon—and of course they cannot—the total working strength behind the program would be somewhere between 7 and 8 thousand. On this basis, if the Workers Party enters the May 30th convention (now set for June 17th—Ed. Note), nominates a man like LaFollette, and campaigns for him, its position will be misunderstood by its own membership; its militance will be dissipated; its members will be dissipated; its members will be dis- credited with the labor movement; its candidates will be crushingly defeated, and the Party will lose itself in the maze of American politics.

Our difficulty to balance our program so stated, viz., still compliment each other.

Even supposing that LaFollette should get a heavy vote, as Roosevelt did in 1912, with the aid of many good Socialists, who were out to split the old parties and to spread the “faith,” the same thing would happen in 1928 that happened in 1916. The workers who broke away in 1912 were back voting for the old parties in 1916, because they were not intelligent voters but protest voters, who ceased to protest as soon as their immediate cause of complaint was removed. The same result followed the heavy Hillquit vote of 1917 in New York City.

A highly intelligent and disciplined body of workers should be able to support a stalwart upholder of the established order like LaFollette and then come back to the Workers Party without having their faith and their enthusiasm shattered. Since you have no such body of workers at your disposal, by such tactics you would be simply squandering and dissipating the small group that you do now control.

Where a revolutionary movement faces a vast wall of ignorance and opposition like that which now exists in the United States, it must preserve stern integrity, strict discipline, and live revolutionary ideals. Otherwise it will not last for a decade.

Let me sum the matter up in this way:

1. As a matter of economics, I agree with you and with Pepper.

2. I am just as anxious as you are to see a real left wing movement develop in America.

3. As a matter of tactics, you and he are following a policy based on Russian experience, which is quite unfitted to cope with the situation you confront in the United States, and which you drive your party to ruin if you pursue it.

Scott Nearing.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v02a-n046-supplement-may-10-1924-DW-LOC.pdf