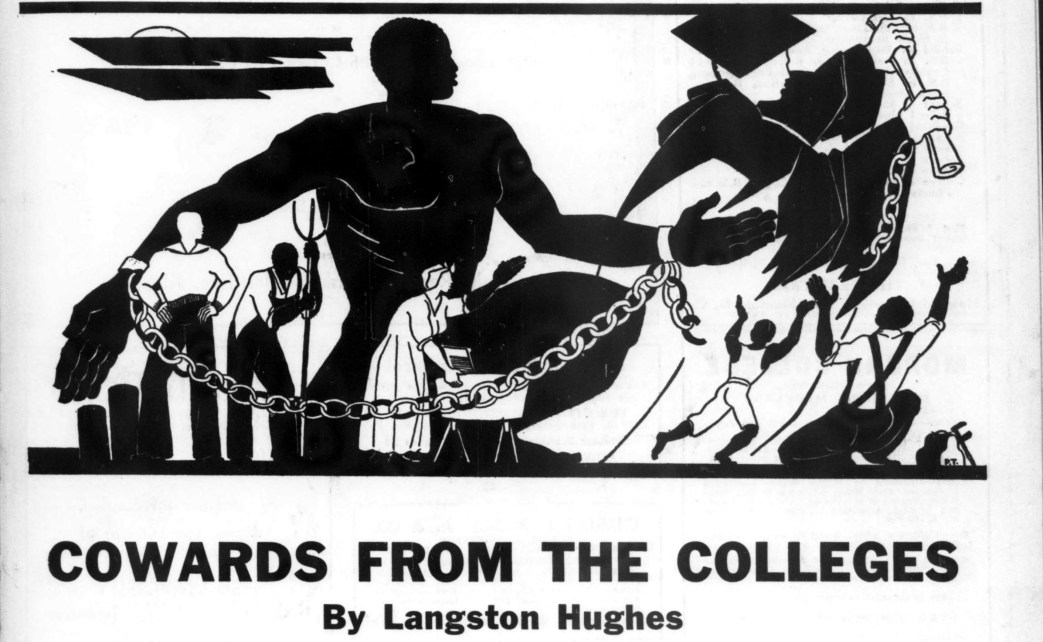

Justly famous, this blistering essay by Langston Hughes on the life in, and role of, Black colleges in the U.S. was written after a 1932 lecture tour for W.E.B. Du Bois’ ‘Crisis.’

‘Cowards from the Colleges’ by Langston Hughes from The Crisis. Vol. 41 No. 8. August, 1934.

TWO YEARS ago, on a lecture tour, I visited more than fifty colored schools and colleges from Morgan College in Baltimore to Prairie View in Texas. Everywhere I was received with the greatest kindness and hospitality by both students and faculties. In many ways, my nine months on tour were among the pleasantest travel months I have ever known. I made many friends, and this article is in no way meant as a disparagement of the courtesies and hospitality of these genial people—who, nevertheless, uphold many of the existing evils which I am about to mention, and whose very geniality is often a disarming cloak for some of the most amazingly old-fashioned moral and pedagogical concepts surviving on this continent.

At every school I visited I would be shown about the grounds, and taken to view the new auditorium or the modern domestic science hall or the latest litter of pigs born. If I took this tour with the principal or some of the older teachers, I would often learn how well the school was getting on in spite of the depression, and how pleasant relationships were with the white Southerners in the community. But if I went walking with a younger teacher or with students, I would usually hear reports of the institution’s life and ways that were far from happy.

For years those of us who have read the Negro papers or who have had friends teaching in our schools and colleges, have been pretty well aware of the lack of personal freedom that exists on most Negro campuses. But the extent to which this: lack of freedom can go never really came home to me until I saw and experienced myself some of the astounding restrictions existing at many colored educational institutions.

To set foot on dozens of Negro campuses is like going back to mid-Victorian England, or Massachusetts in the days of the witch-burning Puritans. To give examples, let us take the little things first. On some campuses grownup college men and women are not allowed to smoke, thus you have the amusing spectacle of twenty-four-year-old men sneaking around to the back doors of dormitories like little boys to take a drag on a forbidden cigarette. At some schools, simple card playing is a wicked abomination leading to dismissal for a student—even though many students come from homes where whist and bridge are common amusements. At a number of schools, dancing on the campus for either faculty or students is absolutely forbidden. And going to dancing parties off campus is frequently frowned upon. At one school for young ladies in North Carolina, I came across an amusing rule which allowed the girls to dance with each other once or twice a week, but permitted no young men at their frolics. At some schools marching in couples is allowed instead of dancing. Why this absurd ban on ballroom dancing exists at colored schools, I could never find out—doubly absurd in this day and age when every public high school has its dances and “proms,” and the very air is full of jazz, North and South, in inescapable radio waves.

One of the objects in not permitting dancing, I divined, seems to be to keep the sexes separated. And in our Negro schools the technique for achieving this—boys not walking with girls, young men not calling on young ladies, the two sexes sitting aisles apart in- chapel if the institution is co-educational—in this technique Negro schools rival monasteries and nunneries in their strictness. They act as though it were unnatural for a boy and girl to ever want to walk or talk together. The high points of absurdity during my tour were campuses where young men and women meeting in broad daylight in the middle of the grounds might only speak to one another, not stand still to converse lest they break a rule; and a college in Mississippi, Alcorn—where to evening lectures grownup students march like school kids in and out of the hall. When I had finished my lecture at Alcorn, the chairman tapped a bell and commanded, “Young ladies with escorts now pass.” And those few girls fortunate enough to receive permission to come with a boy rose and made their exit. Again the bell tapped and the chairman said, “Unescorted young ladies now pass.” And in their turn the female section rose and passed. Again the bell tapped. “Young men now pass.” I waited to hear the bell again and the chairman saying, “Teachers may leave.” But apparently most of the teachers had already left, chaperoning their grown-up charges’ back to the dormitories. Such regimentation as practiced in this college was long ago done away with, even in many grammar schools of the North.

Apparently the official taboo on male and female companionship extends even to married women teachers who attend summer seminars in the South, and over whom the faculty extends a prying but protective arm. The wife of a prominent educator in the South told me of being at Hampton for one of their summer sessions a few years ago. One night her husband called up long distance just to hear his wife’s voice over the phone. Before she was permitted to go to the phone and talk to a MAN at night, however, she had to receive a special permit from, I believe, the dean of women, who had to be absolutely assured that it really was her husband calling. The long distance phone costs mounted steadily while the husband waited but Hampton did its part in keeping the sexes from communicating. Such interference with nature is a major aim on many of our campuses.

Accompanying this mid-Victorian attitude in manners and morals, at many Southern schools there is a great deal of official emphasis placed on heavy religious exercises, usually compulsory, with required daily chapels, weekly prayer meetings, and Sunday services. Such a stream of dull and stupid sermons, uninspired prayers, and monotonous hymns—neither intellectually worthy of adult minds nor emotionally existing in the manner of the old time shouts—pour into students’ ears that it is a wonder any young people ever go to church again once they leave college. The placid cant and outworn phrases of many of the churchmen daring to address student groups today makes me wonder why their audiences are not bored to death. I did observe many young people going to sleep.

But there are charges of a far more serious nature to bring against Negro schools than merely that of frowning on jazz in favor of hymns, or their horror of friendly communication between boys and girls on the campuses. To combine these charges very simply: Many of our institutions apparently are not trying to make men and women of their students at all—they are doing their best to produce spineless Uncle Toms, uninformed, and full of mental and moral evasions.

I was amazed to find at many Negro schools and colleges a year after the arrest and conviction of the Scottsboro boys, that a great many teachers and students knew nothing of it, or if they did the official attitude would be, “Why bring that up?” I asked at Tuskegee, only a few hours from Scottsboro, who from there had been to the trial. Not a soul had been, so far as I could discover. And with demonstrations in every capital in the civilized world for the freedom of the Scottsboro boys, so far as I know not one Alabama Negro school until now has held even a protest meeting. (And in Alabama, we have the largest colored school in the world, Tuskegee, and one of our best colleges, Talladega.)

But speaking of protest meetings— this was my experience at Hampton. I lectured there the week-end that Juliette Derricotte was killed. She had been injured in an automobile wreck on her way home from Fisk University where she was dean of women, and the white Georgia hospitals would not take her in for treatment, so she died. That same week-end, a young Hampton graduate, the coach of Alabama’s A.&M. Institute at Normal was beaten to death by a mob in Birmingham on his way to see his own team play. Many of the Hampton students and teachers knew Juliette Derricotte, and almost all of them knew the young coach, their recent graduate. The two happenings sent a wave of sorrow and of anger over the campus where I was a visitor. Two double tragedies of color on one day—and most affecting to students and teachers because the victims were “of their own class,” one a distinguished and widely-travelled young woman, the other a popular college graduate and athlete.

A note came to me from a group of Senior students asking would I meet with a student committee. When a young man came to take me to the meeting, he told me that it would concern Juliette Derricotte and their own dead alumnus. He said that the students wanted to plan a protest on the campus against the white brutality that had brought about their death.

I was deeply touched that they had called me in to help them, and we began to lay plans for the organization of a Sunday evening protest meeting, from which we would send wires to the press and formulate a memorial to these most recent victims of race hate. They asked me would I speak at this meeting and I agreed. Students were chosen to approach the faculty for permission to use the chapel. We were to consult again for final plans in the evening.

At the evening committee meeting the faculty had sent their representative, Major Brown, a Negro (who is, I believe, the dean of men), to confer with the students. Major Brown began by saying that perhaps the reports we had received of the manner of these two deaths had not been true. Had we verified those reports?

I suggested wiring or telephoning immediately to Fisk and to Birmingham for verification. The Major did not think that wise. He felt it was better to write. Furthermore, he went on, Hampton did not like the word “protest.” That was not Hampton’s way. He, and Hampton, believed in moving slowly and quietly, and with dignity.

On and on he talked. When he had finished, the students knew quite clearly that they could not go ahead with their protest meeting. (The faculty had put up its wall.) They knew they would’ face expulsion and loss of credits if they did so. The result was that the Hampton students held no meeting of protest over the mob-death of their own alumnus, nor the death on the road (in a Negro ambulance vainly trying to reach a black hospital) of one of the race’s finest young women. The brave and manly spirit of that little group of Hampton students who wanted to have the protest was crushed by the official voice of Hampton speaking through its Negro Major Brown.

More recently, I see in our papers where Fisk University, that great (?) center of Negro education and of Jubilee fame has expelled Ishmael Flory, a graduate student from California on a special honor scholarship, because he dared organize a protest against the University singers appearing in a Nashville Jim-crow theatre where colored people must go up a back alley to sit in the gallery. Probably also the University resented his organizing, through the Denmark Vesey Forum, a silent protest parade denouncing the lynching of Cordie Cheek who was abducted almost at the very gates of the University.

Another recent news item tells how President Gandy of Virginia State College for Negroes called out the cracker police of the town to keep his own students from voicing their protest as to campus conditions. Rather than listen to just grievances, a Negro president of a large college sends for prejudiced white policemen to break his students heads, if necessary.

And last year, we had the amazing report from Tuskegee of the school hospital turning over to the police one of the wounded Negroes shot at Camp Hill by white lynchers because the share-croppers have the temerity to wish to form a union—and the whites wish no Negro unions in Alabama. Without protest, the greatest Negro school in the world gives up a poor black, bullet riddled share-cropper to white officers. And awhile later Tuskegee’s president, Dr. Moton, announces himself in favor of lower wages for Negroes under the N.R.A., and Claude Barnett, one of his trustees, voices his approval of the proposed code differentials on the basis of color.

But then, I remember that it is Tuskegee that maintains a guest house on its campus for whites only! It also maintains a library that censors all books on race problems and economics to see that no volumes “too radical” get to the students. And during my stay there several young teachers whispered to me that a local white trustee of the school receives his Negro visitors only on the porch, not in his house. It is thus that our wealthiest Negro school with its” two thousand six hundred students expects to turn out men and women!

Where then would one educate “Uncle Toms?”

Freedom of expression for teachers in most Negro schools, even on such unimportant matters as to rouge or not to rouge, smoke or not smoke, is more or less unknown. Old and mossbacked presidents, orthodox ministers or missionary principals, control all too often what may or may not be taught in the class rooms or said in campus conversation. Varied examples of suppression at the campuses I visited are too numerous to mention in full in a short article, but they range all the way from an Alabama secondary school that permitted no Negro weeklies like the Chicago Defender or the Pittsburgh Courier in its library because they were “radical”, to the great university of Fisk at Nashville where I asked a nationally known Negro professor and author of several books in his field what his attitude toward communism was, and received as an answer, “When I discuss communism on this campus, I will have a letter first from the president and the board of trustees.”

There is at the Negro schools in the South, even the very well-endowed and famous ones that I have mentioned, an amazing acquiescence to the wishes of the local whites and to the traditions of the Southern color-line. When programs are given, many schools set aside whole sections in their own auditoriums for the exclusive use of whites. Often the best seats are given them, to the exclusion of Negro visitors. (But to insert into this article a good note, Mary McLeod Bethune, however, permits no such goings-on at Bethune-Cookman Institute in Daytona, one of the ‘few campuses where I lectured that had not made “special provisions” for local white folks. A great many whites were in the audience but they sat among the Negroes.) Even where there is no official campus segregation (such as Tuskegee’s white guest house, or Hampton’s hospital where local whites are given separate service) both teachers and students of Negro colleges accept so sweetly the customary Jim-crowing of the South that one feels sure the race’s emancipation will never come through its intellectuals. In North Carolina, I was given a letter to the state superintendent of the Negro schools, a white man, Mr. N.C. Newbold. When I went to his office in Raleigh to present my letter, I encountered in his outer office a white woman secretary busy near the window quite a distance from the door. She gave me a casual glance and went on with what she was doing. Then some white people came into the office. Immediately she dropped her work near the window and came over to them, spoke to them most pleasantly, and ignored me entirely. The white people, after several minutes of how-are-you’s and did-you-enjoy-yo’self-at-the-outing-last-week, said that they wished to see Mr. Newbold. Whereupon, having arrived first and having not yet been noticed by the secretary, I turned and walked out.

When I told some Negro teachers of the incident, they said, “But Mr. Newbold’s not like that.”

“Why, then,” I asked, “does he have that kind of secretary?”

Nobody seemed to know. And why had none of the Negro teachers who call at his office ever done anything about such discourteous secretaries? No one knew that either.

But why (to come nearer home) did a large number of the students at my own Lincoln University, when I made a campus survey there in 1929, declare that they were opposed to having teachers of their own race on the faculty? And why did they then (and probably still do) allow themselves to be segregated in the little moving picture theatre in the nearby village of Oxford, when there is no Jim-crow law in Pennsylvania—and they are some four hundred strong? And why did a whole Lincoln University basketball team and: their coach walk dociley out of a cafe in Philadelphia that refused to serve them because of color? One of the players explained later, “The coach didn’t want to make a fuss.”

Yet Lincoln’s motto is to turn out leaders! But can there be leaders who don’t want to make a fuss?

And can it be that our Negro educational institutions are not really interested in turning out leaders at all? Can it be that they are far more interested in their endowments and their income and their salaries than in their students?

And can it be that these endowments, incomes, gifts—and therefore salaries— springing from missionary and philanthropic sources and from big Northern boards and foundations—have such strings tied to them that those accepting them can do little else (if they wish to live easy) but bow down to the white powers that control this philanthropy and continue, to the best of their ability, to turn out “Uncle Toms?”

A famous Lincoln alumnus, having read my undergraduate survey of certain deplorable conditions on our campus, said to me when I graduated there, “Your facts are fine! Fine! Fine! But listen, son, you mustn’t say everything you think to white folks.”

“But this is the truth,” I said.

“I know, but suppose,” continued the old grad patronizingly, in his best fatherly manner, “suppose I had always told the truth to white folks? Could I have built up that great center for the race that I now head in my city? Where would I have gotten the money for it, son?”

The great center of which he spoke is a Jim-crow center, but he was very proud of having built it.

To me it seems that the day must come when we will not be proud of our Jim-crow centers built on the money docile and lying beggars have kidded white people into contributing. The day must come when we will not say that a college is a great college because it has a few beautiful buildings, and a half dozen Ph. D.’s on a faculty that is afraid to open its mouth though a lynching occurs at the college gates, or the wages of Negro workers in the community go down to zero!

Frankly, I see no hope for a new spirit today in the majority of the Negro schools of the South unless the students themselves put it there. Although there exists on all campuses, a distinct cleavage between the younger and older members of the faculties, almost everywhere the younger teachers, knowing well the existing evils, are as yet too afraid of their jobs to speak out, or to dare attempt to reform campus conditions. They content themselves by writing home to mama and by whispering to sympathetic visitors from a distance how they hate teaching under such conditions.

Meanwhile, more power to those brave and progressive students who strike against mid-Victorian morals and the suppression of free thought and action! More power to the Ishmael Florys, and the Denmark Vesey Forum, and the Howard undergraduates who picket the Senate’s Jim-crow dining rooms—for unless we develop more and ever more such young men and women on our campuses as an antidote to the docile dignity of the meek professors and well-paid presidents who now run our institutions, American Negroes in the future had best look to the unlettered for their leaders, and expect only cowards from the colleges.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1934-08_41_8/sim_crisis_1934-08_41_8.pdf