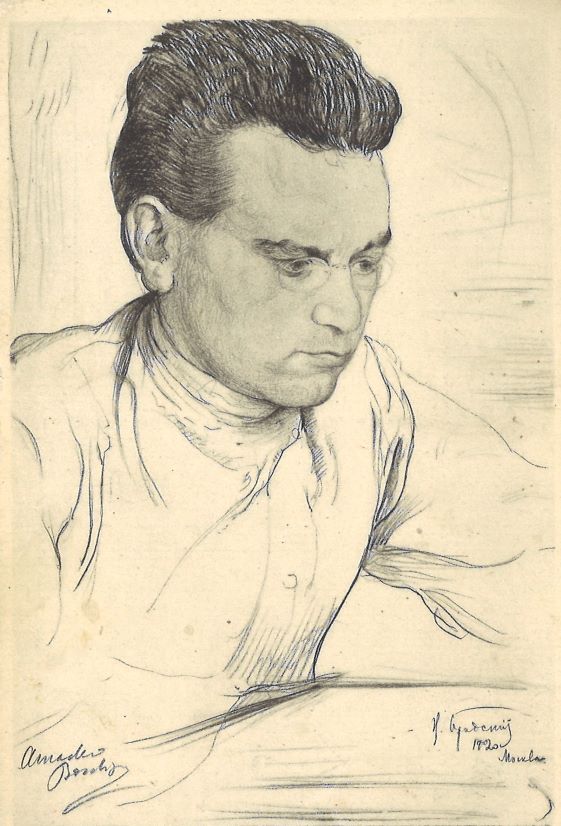

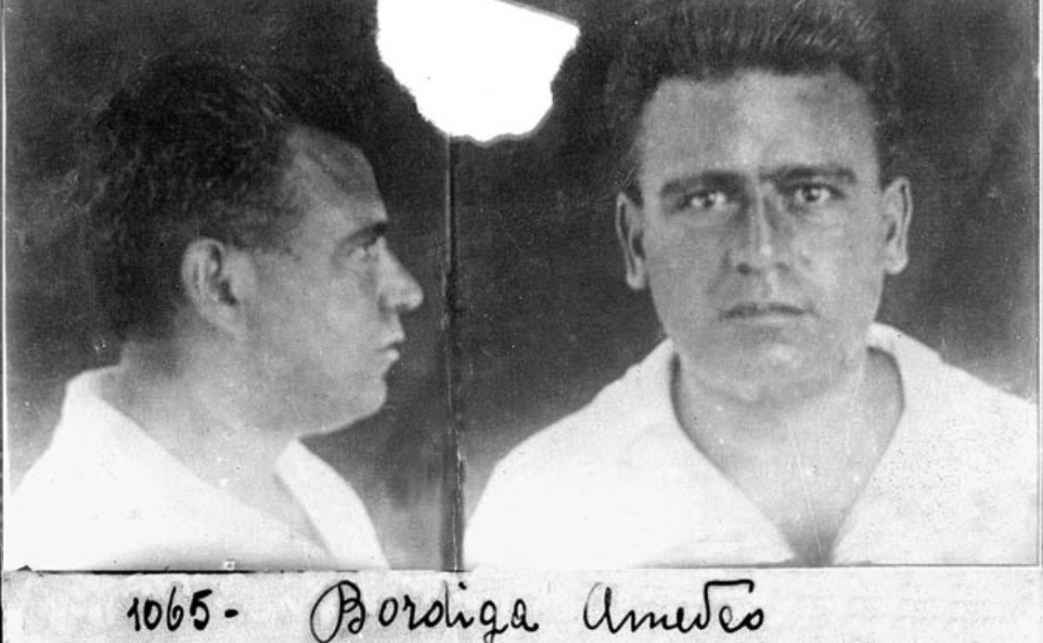

Amadeo Bordiga was a founder of the Third International and, as a ‘Left Communist’, a key figure in many of its early debates. His last personal intervention into International was in the discussions at its Sixth Enlarged Executive Committee meeting held in February, 1926. In this speech he stands, nearly alone, against ‘Bolshevization’ of the Comintern. Below are his full initial speech and his response to Bukharin’s refutation. After his return to Italy he would be arrested and sent to exile the island of Ustica with Gramsci, his factional opponent in the C.P.I, which he would stay in until expulsion in 1930. My guess is that the speech going through multiple translations is responsible for some of the wonkier sentences.

‘On ‘Bolshevization’: Speech to the Executive Committee of the Communist International’ by Amadeo Bordiga from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 20. March 17, 1926.

Comrade Ferdi, Chairman, declared the session open and called upon Comrade Bordiga to speak.

Comrade Bordiga (Italy):

Comrades, I think it is absolutely impossible to limit our discussion to the scope of the draft theses and of the report. We have a situation in the International which cannot be considered satisfactory.

In a certain sense we are in a state of crisis. A summary review of the history of the C.I. will show that there is a consensus of opinion concerning the existence of a crisis.

After the disaster of the Second International the formation of the Communist International was accomplished on the strength of the slogan: Formation of Communist Parties. Everyone agreed that there existed objective conditions for struggle, but we were minus the organ of this struggle.

At the Third Congress, after the experience of many events and especially of the March Action in Germany in 1921, the International was compelled to admit that the formation of Communist Parties alone was not sufficient. Fairly strong sections of the Communist International had been formed in all the most important countries, but the problem of revolutionary action had not been solved.

The Third Congress had to discuss this problem and had to place on record that it is not enough to have Communist Parties, even if all the objective conditions for struggle are there, that it is essential that our Parties be able to exercise influence over the masses.

I am not at all against the conception of the Third Congress of the necessity for mass solidarity, as a premise to the final offensive, but I would like to say that such a conception, namely as expressed by the Third Congress, does not by any means include the idea of united front tactics: the latter corresponds to a defensive position created by a capitalist offensive against which endeavours are made to bring out all the workers on the basis of immediate demands.

The application of the United Front led to errors after the Third Congress and especially after the Fourth Congress. In our opinion, these tactics were adopted without making their real meaning perfectly clear. We were all in agreement when it was a question of making the economic and immediate demands the basis of these tactics, demands which sprang up owing to the offensive of the enemy. But when there was an intention of making the new formulae of a Workers’ Government the basis of a United Front, we opposed this, declaring that this slogan made us exceed the limits of effective revolutionary tactics.

After the October defeat in Germany in 1923, the International recognised that the mistake had been made.

But instead of introducing a thorough change into the decisions of the Fourth Congress, all that was done was to hit out against certain comrades. Scapegoats had to be found. And they were found in the German Party. There was an absolute failure to recognise that the entire International was responsible. Nevertheless, the theses were revised at the Fifth Congress and a new formula of the Workers’ Government was issued.

Why did we disagree with the theses of the Fifth Congress? In our opinion, the revisions were not adequate. The theses and speeches were very Left, but this was not enough for us: we foresaw what would happen after the Fifth Congress and that is why we are not satisfied.

I will deal now with Bolshevisation, and I assert that its balance sheet is unsatisfactory from all viewpoints. It was said: We have only one Party which has accomplished a revolutionary victory the Russian Bolshevik Party. Hence we must follow the path pursued by the Russian Party in order to achieve victory. This is quite true, but it isn’t enough. The Russian Party carried on its struggle under special conditions, that is to say, in a country where the feudal autocracy had not yet been beaten by the capitalist bourgeoisie. For us it is essential to know how to attack a modern, democratic bourgeois State which on the one hand has all the resources to corrupt and mislead the proletariat and which on the other hand is even more efficient on the field of armed struggle than the Tsarist autocracy. This problem will not be found in the history of the Russian Communist Party and if one interprets Bolshevisation in the sense that the revolution of the Russian Party provided the solution for all strategic problems of the revolutionary struggle, the conception of Bolshevisation is inadequate. The glorious experience of the Russian Party is precious to us from the viewpoint of the revolution, of tactical problems, but apart from this we must have something else. It is only in the domain of doctrine that the lesson of the Russian Revolution and of the restoration of Marxism by Lenin are conclusive.

Much of the problem of Bolshevisation will be found in the question of the reorganisation of the Parties. In 1925 it was said that the entire organisation of the Sections of the International was wrong, that one had not yet applied even the ABC of organisation. Very strange that one should not have noticed this before. Eight years after the victory in Russia we are told: The other Parties are impotent because they are not organised on the basis of factory nuclei. Well, Marx and Lenin are there to show us that organisation is not everything in the revolutionary struggle. To solve the problem of revolution, it is not enough to issue an organisational formula. These are problems of forces and not of forms.

I contest that the Communist Party must be necessarily organised on a factory nucleus basis. In the organisation theses brought forward by Lenin at the Third Congress, it is repeatedly stated that in questions of organisation there can be no solution which is equally good for all countries. We do not contest that the situation in Tzarist Russia was such as to justify the Russian Communist Party to organise itself on a factory nucleus basis. But we believe that nuclei present certain disadvantages in other countries. Why?

Above all, because a group of workers organised as a nucleus cannot have the opportunity for discussing all political questions.

You will probably say that we demand what is demanded by all Right elements, that is to say, the organisation of workers into sections where the intellectuals lead in all discussions. But this danger will always exist and one must bear in mind that the working class cannot do without intellectuals, which, whatever one may say, are necessary to it.

The movement needs organisers and agitators who must be recruited among the deserters of the other classes or else among advanced workers. But the danger of corruption and demagogy inherent to these elements once they become leaders is as great with them as with the intellectuals. In certain cases, ex-workers have played the most ignominious role in the labour movement. Moreover, does organisation on a factory nucleus basis put an end to the role of the intellectuals? They constitute at present, together with ex-workers, the entire apparatus of the Party and their role has become more dangerous. Then you cannot be ignorant of the fact that there is a complete technical solidarity between the state apparatus and the employers, and when a workman endeavours to organise the others, the employer calls in the police. This makes the activity of the Party in the factories much more dangerous. It is an easy matter for the bourgeoisie to find out what work is done in the factory and that is why we propose to have the basic organisation of the Party outside the factories.

In Russia the relations between the capitalist employers and the State were different. Moreover, the problem of power was bound to arise and the danger of non-political “labourism” which we see in the nuclei was not so great.

Does this attitude of ours mean that we will neglect Party work in the factories? Certainly not, one must have the Party organisation in the factories, but it must not form the basis of the Party. It is essential to have Party organisations in the factories to carry on the policy of the Party. It is impossible to be in contact with the working class without a factory organisation.

Therefore, we are for a network of Communist organisations in the factories but political discussions must take place in the territorial sections.

I will deal now with another point of view: that of the internal regime of the Party and of the Communist International. Another discovery has just been made: what we hitherto Lacked in all the Sections is iron Bolshevik discipline, of which the Russian Party is setting us an example. It must be forbidden to form fractions, and all Party members, regardless of their opinion, are compelled to participate in the common work even in the Central Committee.

It is a fact that we must have a Communist Party which is absolutely united, a Party without divergencies of opinion and different groups within it. But how is this to be achieved? How are we to arrive at an effective and vital unity and not at the paralisation of the Party? At the first signs of crisis within the Party one must find out its causes. Our view is that they cannot be found by means of a kind of criminal code of the Party. Lately a certain kind of sport has been indulged in in the Parties, a pastime which consists in hitting out, intervening, breaking up, illtreating and it very frequently happens that very good revolutionaries get hit. I think that this terrorist sport within the Party has nothing in common with our work. We must hit and break up capitalism, it is on this field that our Party can show its prowess and I believe that on this field we will witness the defeat of many of our internal terrorists within the iron fist! The real merit does not consist in crushing rebellion but in preventing it. The best proof of unity is its results and not a regime of threats and terror. Those elements who deviate in a decisive manner from the common path must be hit hard. But if the application of the criminal code becomes the order of the day in a society this means that this society is far from perfect.

Sanctions must be applied in exceptional cases, they must not be the rule, a pastime and an ideal of the leaders of a Party. It is all this which needs changing if we are to form a solid block.

By the by, there are very good paragraphs on this subject in the theses before us. A little more freedom will be given. But will this be put into practice? The fact is that we need a healthier regime in the Party, it is absolutely necessary that the Party should be able to form an opinion of its own. One must pursue this aim in order that the rank and file of the Party should have a common political conscience.

I will deal now with fractions. I take the view that to raise the problem of fractions as a moral problem, as a problem of criminality is utterly wrong. there a historic example showing that any comrade has ever formed a fraction for his own amusement? Such a thing has never happened. Experience has shown that opportunism makes its appearance among us always in the guise of unity. Moreover, the history of fractions goes to show that if fractions do not honour to the Parties in which they have been formed, they do honour to those who have formed them. The history of fractions is the history of Lenin.

The formation of a fraction is an indication that something is wrong, and to remedy the evil one must not strike but one must rather investigate what was the historic cause of the disease which necessitated the formation of the fraction. Fractions are not the disease, they are only the symptom, and if you want to cure a disease, you must first of all discover it and understand it.

Let us take for example, the crisis of the French Party. What was the procedure in this Party against the fractions? A very bad procedure, for instance, with respect to a syndicalist fraction which is on the point of formation. Certain comrades, expelled from the Party, have returned to their former affections and are publishing a periodical to explain their ideas. They are, of course, wrong, but what has caused them to do so. The naughty boys, Rosmer and Monatte, did not act on the impulse of a caprice. The causes for their action are to seek in the errors of the French Party and of the entire International.

These fundamental errors threaten to reappear within the proletariat because the International and the Communist Parties have not been able to demonstrate by deeds the enormous difference which exists between a policy conceived in a revolutionary and Leninist spirit and that of the old Social Democratic Parties.

It is the fault of the erroneous policy of the International if the idea still prevails among us (so completely eschewed by us in theory and on the field of action) that the Party and political work are things not fit for the working class and that the latter must follow the saner and safer path of purely economic action through the trade unions. It is a fact that our policy lends itself to being confused with the vulgar art or technique common to all who come into touch with politics.

The Right Fraction in France, I do not hesitate saying so, is a healthy fraction, it does not in itself represent the permeation of petty bourgeois elements.

It is the reflex of the healthy discontent of the proletariat with the unsatisfactory internal regime of the Party and with the contradictions in its policy, in spite of the utterly false rectifications which it proposes on the tactical field.

To correct errors it is not sufficient to chop off heads, one should rather find out and eliminate the initial errors which cause the discontent and determine the formation of fractions.

It is said to us that the system of Bolshevising is based upon the fact that the action of every central committee is directed by the Communist International, by which the minorities in the Party are offered a security. On this occasion it is sufficient to repeat the criticism which already has been made several times to the kind of connection between the International Executive Committee and the sections; it is artificial enough and is based upon considerations of an inner diplomatic character as well as on the necessity of parliamentary manoeuvres inside our international meetings. The intervention of the International Executive Committee comes nearly always unexpectedly and hits those elements with which a general solidarity of the International has been brought about, in a thoroughly compromising manner. It was not different with the Open Letter to the German Party which was published in a moment when the Left leadership of the C.P.G. was regarded everywhere as the authentic representative of the Comintern, of Leninism, of the V. World Congress and of the victory of the Bolshevisation.

Yet we are told: even if there are some shortcomings in the kind of the international connections, the leading role of the Russian Party offers us a good way out. Yet here also we must make some reservations. I shall in my later exposition return to the question of the Russian Party and its problems. In passing, it is observed that one must ask where the leading factor of the Russian Party is to be found. Is it the old Leninist guard? But after the last events it is clear that this can split and that both sides can with the same energy claim the right to speak in the name of bolshevism and accuse each other of deviating from true Leninism.

I draw the conclusion from it that this search for å point of support of the system of Bolshevising leads to no fixed, undisputed result. The correct solution is to be found elsewhere. We must base ourselves upon the entire International, on the entire advance guard of the world proletariat. Our organisation can be compared to a pyramid. For all its sides are striving to a common summit. Yet this pyramid places itself upon its top and its centre of gravity is therefore too unsteady. It must be turned upside down, the top must be the other way up in order that it can stand on a firm basis.

Having thus summed up the past action of the International, it is essential to give an appreciation of the present situation and of our future tasks. The general statement concerning stabilisation has been accepted by everyone. There have been certain vacillations with respect to the development of the general crisis of capitalism.

We have before us the perspective of the definite decay of capitalism, but in my opinion certain errors of appreciation have crept in with respect to the perspective.

If we proceed like a scientific society for the study of social events we can arrive at objective conclusions of a more or less optimistic or of a more or less pessimistic character, and this is a manner which does not take events into account. But such a purely scientific perspective will not do for a revolutionary Party which participates in all events, which is in itself a factor. It is essential to have always in readiness a second perspective in accordance with Lenin’s formula which Zinoviev mentioned here (examples of Marxist forecasts regarding the revolution of 1848 and Lenin’s forecasts regarding the Russian Revolution after 1905). The Party cannot renounce its final task, its revolutionary will, even if the cold, scientific perspective is unfavourable. I cannot accept the formula: “The situation is now unfavourable, we no longer have with us the situation of 1920, and this justifies the internal crisis in certain Sections and in the International”.

A changed situation can produce a quantitative but not a qualitative change in the Party. If the Party enters upon the stage of crisis this means that its tactics have been guilty of opportunism. Otherwise, the struggle against opportunism in 1914 would be devoid of meaning.

The epoch of capitalism which had reached its full development before the war has objectively contributed to the explanation of social-patriotism, but from the viewpoint of the revolutionaries of that epoch it could not and should not lead to its justification or even its toleration as something inevitable. If we consider the state of crisis in capitalism to be favourable, not only to a revolutionary attack but also to an adequate preparation of our Party, this means that in order to be able to accomplish our task we expect from history a development particularly adapted to exigencies which originate in a wrong scheme of perspective which must be rejected and fought against. This will be the same in the case of the bad solution of the problem of leaders as criticised by Trotsky in his preface to “1917”, in an analysis with which I agree completely and which does not appertain to the unfavourable situation, but to the general political and tactical errors which have impeded the process of the selection of the revolutionary General Staff.

There is another scheme of perspective which must be fought against and which confronts us when we turn our attention from the purely economic analysis to an analysis of the social and political forces. It is generally accepted that we must consider the fact that a Left Bourgeois Party is in power as a political situation favourable to our preparation and to our struggle. This wrong perspective is first of all a contradiction of the first because it most frequently happens in the state of economic crisis favourable to us that the bourgeoisie organises a Right Government for a reactionary offensive, which means that objective conditions become unfavourable to us for a Marxist solution of the problem.

Generally speaking, it is not true that the fact of a Left bourgeois Government will be favourable to us: the contrary may be the case. Historical examples have shown us how absurd it would be to imagine that in order to lighten our task a so-called middle class government with a liberal programme would make its appearance, a government which would enable us to organise an effective and united struggle against a weakened State apparatus.

In 1919 we witnessed in Germany the access of a Left bourgeois bloc to power. We witnessed the management of affairs in the hands of the Social Democrats. In spite of the military defeat from which Germany had just emerged, the State machine had not been shaken to its foundations.

After we shall have promoted by our tactics the access to power of a Left Government, will we have obtained more favourable conditions for ourselves? No, this is not at all the case. It is a Menshevik conception to imagine that the State machine will be different in the hands of the lower middle classes to what it is in the hands of the big bourgeoisie, and to consider such a period as a transition period leading to the epoch of the seizure of power. Certain parties of the bourgeoisie have an appropriate programme and bring forward appropriate demands with the object of attracting the lower middle classes. Generally speaking, this is not a process in which power passes from one social group to another, it is only a new defensive method of the bourgeoisie against us, and when this takes place we cannot say that this is the most propitious moment for our intervention. This change can be uitilised but only provided our preceding position has been perfectly clear and has not coincided with the demands of the Left Bloc element.

For instance, in Italy. can it be said that Fascism is the triumph of the Right bourgeoisie over the Left bourgeoisie? Certainly not, fascism is something more than that, it is the synthesis of two methods of defence of the bourgeois class. The recent acts of the Fascist Government have clearly shown that the semi-bourgeois and petty bourgeois composition of fascism does not prevent the latter being a direct agent of capitalism. As a mass organisation (the fascist organisation has a million members) it is endeavouring not only to strike down ruthlessly its opponents, especially the adversaries who dare attack the State machine but also to mobilise the masses by means of Social Democratic permeation methods.

On this field fascism has suffered evident defeats. This bears out our point of view on the class struggle but what is most forcibly shown by all this is the absolute impotence of the middle classes. During the last few years they have already accomplished three complete evolutions: in 1919-20 they crowded our revolutionary meetings; in 1921-22 they formed cadres of “black shirts”; in 1923 they went over to the Opposition after Matteotti’s assassination; today they are coming back to Fascism. Always with the strongest is their motto.

The wrong conception of the advantages which we could derive from the access to power of a Left Bloc Government consists in imagining the middle classes capable of an independent solution of the problem of power. In my opinion, there is a very serious error in the so-called new tactic which has been applied in Germany and in France and with which the proposal. made by the Italian Party to the Aventino anti-fascist opposition

is connected. I cannot understand how a Party, so rich in revolutionary traditions as our German Party could hesitate in the face of the accusation of the Social Democrats that it was playing Hindenburg’s game by bringing forward an independent candidature. Generally speaking, the strong point of the bourgeoisie with regard to the ideological counter-revolutionary organisation of the masses consists in offering a political and historical dualism in opposition to the class dualism between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, supported by the Communist Party not as the only dualism possible in the social perspective and in connection with the changes of parliamentary power, but as the only dualism historically capable of bringing about the revolutionary rupture of a class State machine and the establishment of a new State.

But we cannot bring home this dualism to the consciousness of the masses merely by ideological declarations and abstract propaganda. We can only do so by our actions and by the evidence and the clarity of our political position. When it was proposed to the anti-fascist bourgeoisie in Italy to constitute itself as an anti-parliament in which Communists would have participated even if it was stated in our press that no confidence should be placed in these Parties, even if a pretense was made to expose them by this means in reality we contributed to encouraging the masses to expect the overthrow of fascism by the Aventino, to make them believe in the possibility of a revolutionary struggle and the formation of anti-State not on a class basis but on the basis of collaboration with the petty bourgeois elements and even with entirely capitalist groupings. In view of the failure of the Aventino this manoeuvre did not result in bringing the masses into a class front. This new tactic was not only alien to the resolution of the Fifth Congress, it was in my opinion even alien to the principles and the programme of Communism.

Under what aspect can we view our future tasks? This assembly could not consider the problem in all seriousness without considering the fundamental question of the historic connection between Soviet Russia and the capitalist world. The most important problem for us apart from the problem of the revolutionary strategy of the proletariat, of the world movement, of the peasants and the oppressed colonial peoples, is the problem of the State policy of the Communist Party in Russia. This policy will have to solve the problem of class relations in Russia, it will have to adopt the necessary measures with regard to the influence of the peasant class and that of the budding semi-bourgeois sections of the population, it will have to contend with the pressure from outside, a pressure which today is purely economic and diplomatic but might be military tomorrow. In view of the fact that world revolution has not yet developed in the other countries the entire Russian policy will have to be carried on in close contact with the general revolutionary policy of the proletariat.

I do not propose to enter into details concerning these questions but I assert that the main base for this struggle is certainly the working class of Russia and its Communist Party, and that it is also of the utmost importance to have the support of the proletariat of the capitalist States whose class consciousness and the fact that it is in constant contact with the capitalist adversary are indispensable to our movement. The problem of Russian policy cannot be solved within the narrow precincts of the Russian movement, the entire proletarian Communist International would have to do its share in this.

Without such effective collaboration there are dangers ahead not only for revolutionary strategy in Russia but also for our policy in the capitalist States. There is every possibility for tendencies to spring up which would mean an attenuation of the character and the role of the Communist Parties. Already we are attacked on these lines. The attacks certainly do not come from our ranks but from the ranks of the Social Democrats and opportunists. This is connected with the manoeuvre for international Trade Union Unity and with the attitude towards the Second International. All of us here agree that it is absolutely necessary to preserve the revolutionary independence of the Communist Parties. But it is necessary to point out the possibility of a tendency to replace Communist Parties by organisations of a less pronounced character with semi-class aims and neutralised and attenuated political functions. In the present situation it is the bounden duty of us all to defend the strictly Communist organisation of our International against any liquidatory tendencies.

After our criticism of the general lines of policy, can we consider the International, such as it is, sufficiently prepared for this double task of strategy in Russia and strategy in the other countries? Can we expect from this assembly the immediate discussion of all the Russian problems? Unfortunately, the answer must be in the negative.

What we need at once is a serious revision of our internal regime and discussion in our Parties on the problem of tactics throughout the world and of the problems of State policy of Russia. But such an undertaking requires a new course and utterly different methods.

Neither the report nor the theses give us a sufficiently strong basis for all this. What we want is not official optimism, we must realise that we cannot prepare ourselves for the accomplishment of the formidable tasks which await the General Staff of the World Revolution by having recourse to such inadequate means as those which we only too frequently see applied in the internal process of the life of Our Parties.

RESPONSE TO BUKHARIN

Comrade Bordiga (Italy):

Comrades, in my speech I dealt with the general questions of the policy of the International. But several of the speakers did not only speak in reply to my contentions, but also dealt to a certain extent with Italian problems which I had almost left aside. I am compelled to reply very briefly to what has been said here. One hears continually the expression: “Bordiga’s system, Bordiga’s theory, Bordiga’s metaphysics”, and it is always asserted that I am always alone in supporting my ideas and my criticisms. There is an endeavour to represent my attitude as an entirely personal phenomenon. Well, although it happened recently that the Italian Left was officially defeated, I must declare once more that I have come here not to entertain the Congress with individual lucubrations, but with what represents the conception of a group of the Communist movement in Italy.

Bukharin dealt with my speech in a very friendly and cordial manner. Well, although it isn’t necessary to say here that Bukharin is a good polemist, you will allow me to declare that he presents the problems in his own manner and according to the alleged legend concerning Bordiga’s theories.

He attributes to me certain formulae, makes a spirited attack on them and reduces them to smithereens. In his speech he told us that the international regime of the C.I. will undergo a change. But by the very methods of his polemics, he gives us every reason to be pessimistic concerning this regeneration of the international regime.

Bukharin simplifies ideas. It is a great merit to be able to simplify positions and to make them clear in a few words. It is also a very difficult problem to simplify them, not for the sake of pure agitation but by doing one’s share of the serious work which is of interest to all.

Simplification without the demagogy of agitation, such is the great revolutionary problem. Such simplifiers are very few and far between.

In order to show up Bordiga’s contradictions Bukharin places the following argument before us: I had said that the revolution is not a problem of organisational forms. After that I am supposed to have presented the problem of Bolshevisation from the only viewpoint of organisation, proposing for the entire problem merely a change of organisation: the upsetting of the famous pyramid. All this is not true. When dealing with Bolshevisation, I commenced my cristicism from the viewpoint of theory and tactics, that is to say, I said that I considered Bolshevisation not only as organisational work, but as a political problem connected with the actions and tactics of the International. Moreover, you must admit that our entire opposition was with respect to the tactical problems, and it is above all concerning these problems that we have been for a long time past proposing various solutions. It is self-evident that a simple change of organisation is not sufficient to solve the problem. That is why we are awaiting tactical action to see if we have really a sound revolutionary leadership.

Another of Bukharin’s arguments is: Bordiga is against the mechanical application of the Russian experience in the other countries, but in his attempt to deal with the problem in the other countries he is guilty of mechanical application, inasfar as he does not specify the character of the Western movement, that is to say, the existence of big Social Democratic Parties and trade unions. Well, this is not my formula. I say: generally speaking, the entire Russian experience is useful, we must always bear it in mind, but apart from it we must have something else. This means that I do not reject the application, but I say that the experience of the Russian Party alone will not provide the solution. What is the specific character of revolutionary strategy in the West as formulated by me? Bukharin says that in my exposé it was not the existence of big Social Democratic Parties! Well, this is precisely the difference on which I dwelt. After showing the difference between the State apparatus in the Russian and Western revolution, I said that in the Western countries there exists a bourgeois-democratic State apparatus established long ago, a very stable apparatus such as does not exist in the history of the Russian movement, and also that the problem of the possibility of the mobilisation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie is presented in an opportunist sense. Is this anything but the problem of the role of the trade unions and Social Democratic Parties?

My analysis concerns itself exactly with this point. Bukharin cannot say I am contradicting myself.

Now I will say a few words on Italian affairs. Comrade Ercoli spoke against the criticism of the tactics of the Party towards the Aventino, using the argument that I am not in favour of taking the situation into consideration whilst the Central Committee based itself on a complete and exact analysis. Well, without repeating myself, I will say that not only the tactics but also the analysis of the situation were utterly erroneous. There is a report of Comrade Gramsci to the Central Committee in September 1924 which proves that an Aventino success was expected in the autumn when Mussolini was to be superseded in Parliament! The formation of an anti-fascist Government based on the middle classes was, in fact, considered possible: thus the opportunist error is with respect to the estimation of forces and with regard to policy.

Neither is it that the tactics of proposals to the Aventino has proved satisfactory by its success. We maintain that the colossal defeat of the Aventino opposition was not accompanied by a decided movement of the working classes in the direction of the Communist Party because of the lack of clarity in the policy and the attitude of the latter.

As to the assertion that the Left suffered a complete defeat wherever the Party can report progress in the federations with the most successful activity, I must deny it. Milan and Turin have been set against Naples: well, it is these three centres which have provided the Left with a maximum of forces in an equal degree.

I will not enter into the details, although there is no Italian Commission here. I limit myself to saying that at the Congress of our Party we had to make a declaration which called in question the validity of this assertion by appealing to the International.

The preparation of the Italian Congress occupies a rather prominent place in the disreputable internal regime of mechanical compression within our Parties. By means of a deplorable campaign, an accusation of fractionism and secessionism was launched. At the subsequent discussion very peculiar methods were applied. To name one of them: my vote, Bordiga’s vote, member of the basic organisation, was given for the theses of the Central Committee. Just a trifle like this!

But we do not attach much importance to all these stories. The alleged internal defeat has not weakened our attitude. We submitted to everything to save the unity of the Party and faced with the compulsory inclusion into the C.C. we gave in, making at the same time a political declaration which has even reinforced our oppositional attitude.

I maintain, and this has been partly recognised here, that this oppositional attitude which concerns the very substance of questions and has nothing to do with the mean struggle for power and posts in the Party carried on under a pretence of loyalty to the International, is certainly more loyal and useful to the development of the world Communist movement.

Comrades, with respect to the international regime and the upsetting of the pyramid, I do not pretend to reply here to Bukharin’s objections concerning the question of fractions. But the question I am asking myself is: will there be in the future a modification of the International with respect to our internal relations? Does this plenary session prove that a new path will be adopted? On this subject, the declarations of the French and Italian delegates have not done anything to dispel our incredulity, although the theses deal with the realisation of this regime of democracy within the Party. We will wait to see it in operation.

I think that the fraction-hunt will continue with the same results as before. We see this very thing in the German Party. I must say that this method of humiliation is a deplorable method, even when applied to certain political elements against whom I have fought most energetically. I do not think that this system of humiliation is a revolutionary system, particularly as recent examples have shown that attempts were made to apply to it elements who not only have a great past but who are valuable for the future of the revolution. I think that the majority so intent to show its orthodoxy, is probably composed of former oppositionists who suffered humiliation at some time or other. This mania to demolish ourselves must cease if we really mean to lay claim to the leadership of the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat.

The spectacle presented by this session of the Plenum makes me very pessimistic with respect to the forthcoming changes in the International. I will therefore vote against the draft resolution which has been presented.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n20-mar-17-1926-inprecor.pdf