Another of the many incidents of U.S. working class history that ought to be common knowledge, but are largely unknown, even by the left. The city-wide general strike in Philadelphia involving 150,000 workers in 1910.

‘The General Strike in Philadelphia’ by Joseph E. Cohen from International Socialist Review. Vol. 10. No. 11. May, 1910.

The general strike was, first of all, a political strike. It came apparently because the city authorities were in league with the officials of the company to break the strike, and had trampled upon the political liberties of the people in pursuance of that intention, The car men early learned that their strike had political complications and their leaders set themselves, with the general strike committee, to squeeze all they could out of the situation. One of the consequences, naturally, was that the trades unionists of the city turned to political action as never before.

At its inception the general strike had no other purpose in view than to compel the company to deal with the men, or submit the differences between them to fair arbitration, But that was true only superficially. It may fairly be said that, however the matter appeared to the various organizations participating and to the numbers of men and women who were unorganized, it resolved itself into a simple proposition indicated in the formula: A strike of labor against capital.

Still deeper down was the unrest of the people, the dissatisfaction due to the high cost of living, following so closely after the hard times. More than that, it was Philadelphia’s expression of a feeling that is nation wide. Here the atmosphere happened to be surcharged with inflammable gases, requiring only a flame of class consciousness to fire the whole with a spirit of revolt that would take this shape.

The management of the general strike was left in the hands of the committee of ten. It is no exaggeration to say that the strike was properly handled to the extent that it leaned for guidance to the Socialists. There were two avowed Socialists on the committee. Of the two it was Harry Parker who had first broached the idea of calling a general strike, having proposed in November, 1909, at the convention of the American Federation of Labor, that the members cease from labor for two weeks in the event of Gompers, Mitchell and Morrison being sent to jail.

Socialist philosophy tinctured the whole movement. For the United German Trades Socialists penned a ringing appeal, that was printed in German and English, printed by the tens of thousands and carried right off the press out to the large non-union establishments such as Baldwin’s Locomotive Works. Little wonder that the Philadelphia North American remarked editorially:

“Out of this street-car situation, with its almost inevitable general strike, comes a new and acute class consciousness fanned into a dangerous class antagonism…And it is this antagonism, this class war, intangible and immeasurable, that constitutes the largest and the most lamentable hurt to the city. It is, moreover, felt beyond the city and throughout the entire nation.”

Baldwin’s was carried by storm. The superintendents were quick to canvass the sentiment and try to head off a walkout. The shop leaders were called in for a conference. An offer was made to restore the wages of the men to the scale obtaining before the last cut on condition that the men remain at work. The offer was declined. It was made plain that only the car men’s interests were to be considered at that time. Three thousand men came out from this shop, better known as “the little hell on earth.” Many other large non-union plants fell into line. The men at Baldwin’s were promptly organized into a shop federated union, and afterwards advised also to join the unions of their crafts.

Another splendid showing was that made by the textile workers, of whom about 45,000 are said to have turned out, a large percentage being women. Along with the toilers of Baldwin’s they had borne the brunt of the hard times, after having had their resources drained in the important strikes of 1903, 1905 and 1908, aside from numerous smaller difficulties. The textile industry of the city was practically at a standstill.

The building trades department walked out to a man. Many of them had but recently returned to work after being out for some weeks on a sympathetic strike of their own. Every line of business was more or less seriously affected. Many employers permitted their employes to go out, paying them during the continuance of the strike.

The organized workers of only two industries refrained from taking part, that of printing and beer brewing. Both were encased in tightly nailed and rivetted contracts. Their sympathy was entirely with the car men and they contributed liberally to their treasury. The only element of irony in the situation was that due to the fact that the men at the power houses were not organized and could not be induced to come out. Had they been organized, the general strike might have been unnecessary.

According to the estimate of the committee of ten, 150,000 wage earners, organized and unorganized, were involved in the strike. That is to say, the bread of half a million people in the city was touched. The plans of the committee very naturally revolved around the idea of keeping the army together and letting the members feel the strength of their numbers. Quite as naturally, the police authorities endeavored, by entirely arbitrary methods, to divide and scatter that army.

For the first day of the general strike the committee of ten arranged a mass meeting to be held at Independence Square. The mayor and director of public safety forbade it. The committee of ten then modified their plan to the extent of advising the hosts of labor to march past Independence Hall, wherein the Declaration of Independence had once upon a time been adopted. The police tried to break up the parade, going so far as to run their clubs through the American flag. Nevertheless thousands of people gathered beside the cradle of liberty and they will doubtless remember, in the years to come, that on Saturday afternoon, March 5, 1910, the officials of the city of Philadelphia prohibited its citizens from peacefully assembling in the shade of Independence Hall to discuss questions of public moment.

During the next week the committee of ten arranged with the proprietors of a national league base ball park to have a mass meeting within that enclosure. This meeting, too, the police prevented. The thousands that had gathered started to parade down Broad street to the City Hall. Squads of police were ordered to charge the crowd. What followed fell short of being a massacre only because the blue coats did not use their guns. Otherwise it was the greatest exhibition of uncalled for police brutality the city has ever witnessed. Hundreds of people were beaten up, and driven into the side streets, women no less than men.

But in the face of this violence it was remarkable that there were less disturbances while the general strike lasted than before or after it. The fact showed that labor is the real guardian of the peace. So pronounced was the impression this attitude carried with it that when, later on, the police raided a meeting place of car men with a trumped up charge of dynamiting up their sleeves, the grand jury refused to find a true bill against any of the men.

The third and final effort of the committee of ten to demonstrate the extent of the general strike was set for Saturday afternoon, March 19th, when Eugene V. Debs addressed an audience of strikers at the Labor Lyceum. The hall was crowded to the doors; the streets were black with people. Debs was at his best. That afternoon unionism and socialism clasped hands as never before. The incident taught, better than can tomes of theory, the wisdom of working in harmony with the trades unions to the very utmost.

Throughout the length of the strike and following in its wake, trades unions swelled their membership by hundreds and thousands. So unexpected was the influx that the machinists began by ordering a few hundred application blanks but increased the order to three thousand in a few days. Twenty thousand men and women are said to have affiliated themselves within organized labor in two weeks. Philadelphia’s reputation for unionism had previously been very poor. To-day there is no epithet so abhorred as that of “scab.”

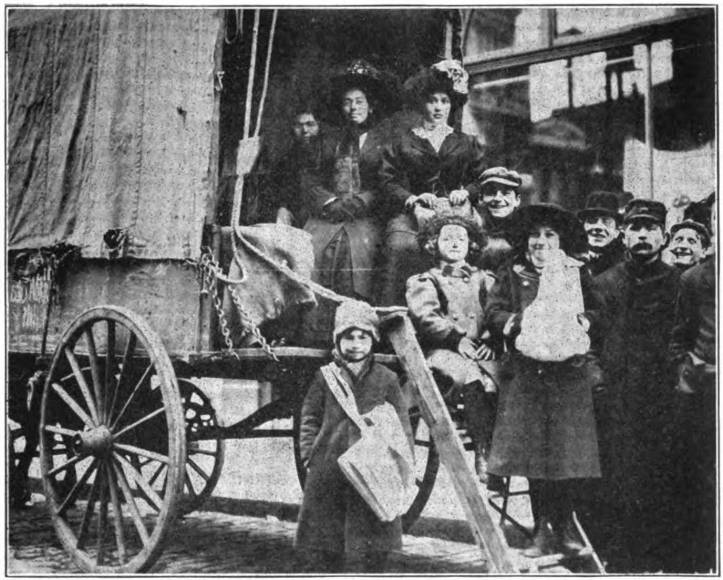

The women did their part in the strike. It does not in the least smack of gallantry to say that they bore their hardships as uncomplainingly as did the men, and made a better showing as walkers and wagon riders. It was no unusual sight to see a car go by with half a dozen men (one or two of whom might be the company’s agents in plain clothes) but not a woman in it. When the general strike was over, they organized the car men’s women folk into an auxiliary, of which Luella Twining was elected president.

But labor’s position, strategic however it was, rested on the edge of a sharp knife. When after two weeks, the general strike rolled into the crest of its popularity, a conference was arranged between the representatives of the company and the car men. The conference came to naught, but was instrumental in creating the impression that the trouble would soon be settled and so prompted the public to patronize the cars. With that the general strike fell to pieces. After another week it was officially declared over. Its only regrettable aftermath was the washing aside in all directions of hundreds of wage earners victimized for having quit work.

Both the car strike and the general strike were a series of surprises. At the first conference held with the car men the company admitted its defeat. Yet it tried by all the devices at its command to deprive the men of the fruits of their victory. It realized that more than its dignity was at stake.

A victory it really was. Its echo was heard in nearby cities where the transit companies voluntarily increased the wages of their employes; it was heard in the Trenton strike which was a complete success; it was heard in the voluntary increase of wages by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and other large corporations. Even at Eddystone, the country annex to the Baldwin works, the men obtained an improvement of their working conditions. The Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company suffered a tremendous pecuniary loss. Yet in the end it jockeyed the car men out of their victory.

The general strike was the most unexpected affair Philadelphia has ever witnessed. It exemplified a spirit of resistance against social wrong that not even the most sanguine of Socialists believed to lurk in the city. Entirely unprepared for such a thing, the wonder of it is, not that it was poorly managed, not that mistakes were made, but that it came out so well. Whatever criticism may be made of the strike is purely incidental. Taken as a whole it was the most magnificent performance ever achieved by the labor of the city. But while the spontaneity of the affair was its most gratifying feature, it was also, under the circumstances, its principal redeeming feature, as well as the source of its weakness. The desire to campaign was very strong; unfortunately too many of the recruits were raw, the line of march strange and the battlefield unexplored. As in all strikes the masters can afford to play the waiting game and tire the workers into submission. Furthermore, when confined to one city a general strike is too largely spectacular. And, more important than all, it cannot spring far above the class-consciousness of the population. That, in the final analysis, determines the immediate aims of the strike and the possibility of their attainment.

We may hazard a guess that, on another occasion, with a like spirit of resistance, supplemented by a more widespread solidarity and a well-defined program, a general strike may be the means of maintaining political rights and securing economic concessions, thereby instilling into the workers that reliance upon their united action which promises so much for them in the future.

But, to use a paradox, the best feature of a general strike is the possibility of not having to resort to it. Rather ludicrous, if not tragic, it appears to ask a whole city of workers to make abundant sacrifice in order to win some slight advantages for a few thousand men and their families. The most satisfactory test of its justification, of course, is the fact that it came to be. Speaking theoretically, nevertheless, it is hoped that in the future labor will be so well organized and disciplined that, while in no wise hampered from displaying its full power when necessary, its whole force will not be hurled into a narrow pass against the enemy when a handful of sharp shooters could do as well or better. We look to see the general strike very rarely called into requisition.

Philadelphia’s experience with the general strike seems to confirm the Socialist contention that labor cannot hope to gain substantial victories by superficial methods. While it must ever be on the alert to make the most of all circumstances, it may as well place its dependence first as last in the development of the intelligence of the whole working class; in short, in the spread of class-consciousness, To the extent that the class-consciousness is acute will the mass of the people press forward.

The sleeper has awakened. But his first movements are awkward; he stumbles and falls. Yet he renews his exertions; he strives on step by step; his eyes become accustomed to the light. It cannot be long before he will stand erect and snap his chains!

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v10n11-may-1910-ISR-gog.pdf