In a program never to be repeated, and immediately regretted, the Federal government gave employment to a bunch of left-leaning out-of-work artists to make theater. Even confined and limited as it was, those brief years saw the best, and in many communities the only, public art ever produced in this country.

‘The Los Angeles WPA Theatre Project’ by Sanora Babb from New Theatre and Film. Vol. 3 No. 6. July, 1936.

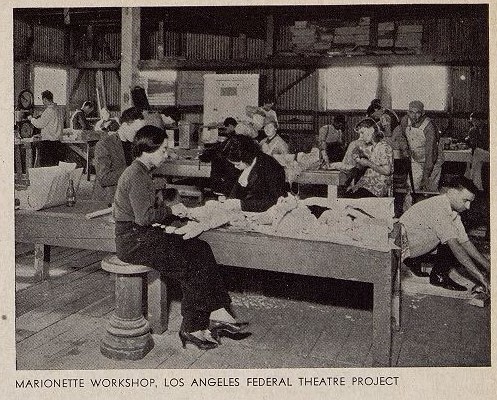

The Los Angeles WPA Federal Theatre Project is housed in an old wholesale electrical supply building with an uncertain elevator, grey cement walls and new-lumber knobless doors. There are 1,440 people: carpenters, office workers, costume makers, maids, publicity men and theatre managers, actors and actresses, musicians, directors and writers, all kinds of workers necessary in the life of the theatre. Besides the general drama groups, there are Yiddish, French, and Negro groups, and a Mexican unit in formation–over five hundred actors in all.

You feel conflict between death and life in this disinterred place, with its ghosts of abandoned industry and its new kind of activity, as you feel it in these “reclaimed” people who are busy on the various floors.

You climb the stone stairs, four and five and six flights, because it is easier than waiting for the decrepit elevator. A thin woman with a sheet of paper filled with figures hurries past half out of breath. A boy goes down with an armful of placards for a new play. (Almost no allowance has as yet been made for advertising; the actors, knowing its necessity, finance it cooperatively from their own pay.)

Some place nearby a violin is playing. Back of the stairs in the dusk a woman’s figure dim against the grey wall under the high dirty window. A young actor tells you she is Buda Dorsay, that she practices there many hours every day. The actor is Walter Zuetelle, baritone, now Master of Ceremonies in the vaudeville unit. He has been in fifteen New York musical shows, has played bits and extras in pictures, and forty-two weeks in the Olvera Street Theatre here in The Streets of New York. After that show closed, he found no more work, until he got on the SERA Project a year ago. He is married, and his wife has been wanting a baby for several years, but living has been too uncertain, and she has been ill; there was no money for doctor’s care or a decent place to live. Under the Federal Theatre Project, with actors’ wages from $85 to $94 a month, there is for the first time in years a little security. They have moved to a little. house at the beach with the hope that hist wife may regain her health. Perhaps they can even afford to have a baby, if the job keeps on, if he, with the others, can look forward to the establishment of a permanent Federal Theatre, run on a cooperative basis, if…He does not mind telling you that he believes the relief theatres will develop a new type of entertainment, and that he is going to vote for Roosevelt. “We’ve at least a chance to live, and work at what we want, and with careful managing a chance to get a few necessary clothes.”

There’s a pretty ingenue, Donya Dean, waiting in a publicity office. She had had three seasons of stock, when she came to Hollywood to try pictures. She was getting along all right, doing extra work, when she suddenly found herself discriminated against, with thousands of others, because she was not registered at Central Casting Agency. Central Casting “cooperates” with the producers; they had a plan to alleviate the desperate conditions among extras: those listed with CC would receive more calls, the surplus workers would be “liquidated.” Donya is one of them; nevertheless, she believes that the purpose of the theatre is to entertain, and that social ideas, social drama are depressing.

You wander into a large room where the Shakespeare unit is rehearsing lustily, under the direction of Gareth Hughes, one time well known stage and screen star, an authority on Shakespeare, still a young man. In Hearst’s daily attacks. on the WPA, he has taken a particularly malevolent pleasure in referring repeatedly to Hughes’ past fame and his present plight on the dole. Just as a matter of fact, Hughes, like many WPA executives, is working on the project on a non-relief ticket, and has never been on relief. (There is at present a ten per cent provision for such extra talent as is needed.) Until he came on the project there was no Shakespearean group. Now rehearsals are going on for a Shakespearean Festival, with music by the WPA symphony orchestra, for the week of April 20th, which will include Midsummer Night’s Dream, Merry Wives of Windsor, Merchant of Venice, and Hamlet. Mr. Hughes prefers to interpret the Shakespeare plays with all the robust life and verve of their original intention, with reverence, but without the lugubrious solemnity of unreality that is commonly felt for them. He knows every line of Shakespeare, and while he is talking, he is also listening to the actors rehearsing, catching up the dialogue here and there. You feel his kindness that is not sentimental, his love for the theatre, his enthusiasm that has awakened and stimulated his actors. Above the noise of movement and shouting, with so much Shakespeare filling the room, you ask Mr. Hughes if he believes the theatre should also portray and interpret the living themes of today, the tremendous social upheaval of the present.

“By all means! The social theatre has its place, it could and should interpret life to the masses. We need new theatre, new themes to replace the degenerate offerings of the sex-ridden drawing room dramas of the commercial stage.

Mr. Hughes is busy again. You sit down with some women, and you get into conversation with Truly Shattuck, once- famous musical comedy prima donna, who made the first experimental talking picture for Thomas Edison in 1913. A lively old Falstaff comes out of a scene, and sits down to talk. Everyone nearby listens to him. He is Frank Brownlee, who has been on the stage forty-two years, who once retired on his income. Since 1931 he has tried to get work so that he and his elderly wife could eat and have a place to live. After drifting from “worse to worse” he finally got on relief this year. “People are always hungry,” he says, “to see a play that reflects current life. They always have been and always will be. They like to identify themselves and their situations with those of the actors. If the federal theatres can keep free of cheap politics, that’s one of the good chances for revival. The commercial theatre is bucking too many other interests.”

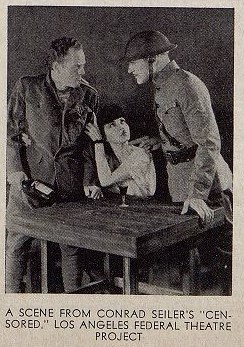

You go to see Max Pollock, who put on Formation Left for the Los Angeles Contemporary Theatre, and who is now directing the Modern Drama group. They are preparing Conrad Seiler’s Censored and Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. “These are artistically moving plays,” Mr. Pollock tells you, “but this is not enough. The plays we are permitted to do are nothing to what we have here to produce. We are told to produce vital, moving, timely plays, but if we do what happens?” He has no awed reverence for the conventional handling of classics. “If we cannot always use new plays, then I want to produce Shakespeare and Ibsen from a contemporary point of view.” Mr. Pollock feels that men like Howard Miller, who asks repeatedly in meetings for alive, social dramas, will do much to help the Federal Theatre Projects to become something more than dead work arranged only to keep relief clients busy: “It is hard to say what the future of the Federal Theatre will be: the process is so slow, so tremendous. Our only hope is in the youth. I know young people and directors here who would love to do social. plays, because there is nothing else vital in the theatre today but the interpretation of the life around us.”

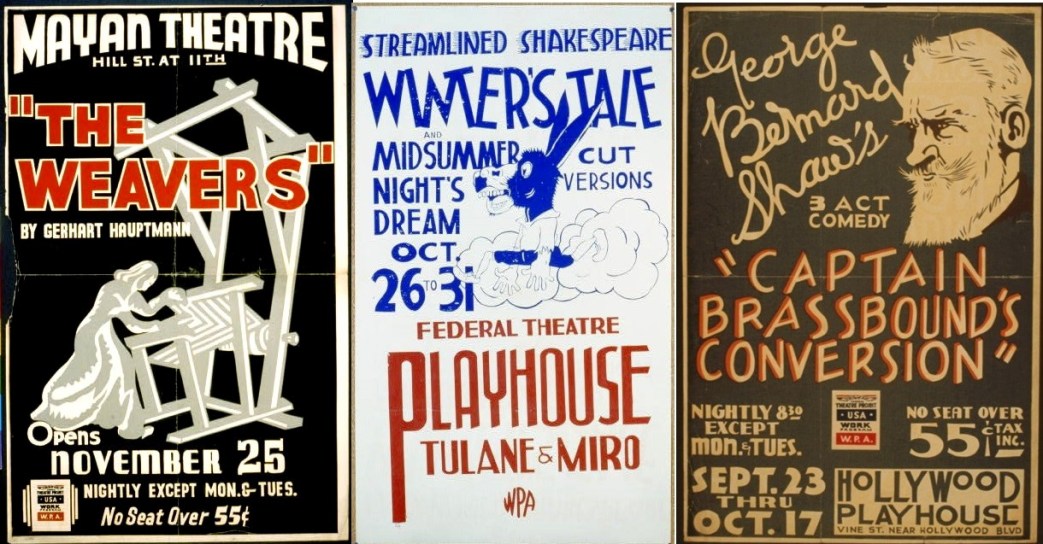

You talk with B.W. Garrett, a former executive at a major motion picture studio, who is the traveling manager for the PWA shows. He tells you that the two Federal Theatres in Los Angeles are the Mayan and Musart; besides these, the shows are booked all over California. There are twelve-day tours covering schools and CCC camps. Arrangements with some of the CCC camps located back in the mountains are carried on entirely by short wave radio, their only means of communication. Only men are permitted on the one-night CCC programs. No curses allowed on the stage, no mention of the deity, no blues. They travel in army trucks, accompanied by an army chaplain.

Black Empire with a Negro and white company of sixty-five and their own. WPA orchestra in the pit, now playing at the Mayan in downtown Los Angeles, is a well-enough produced but romanticized Negro play of the black man ruing the white. You’d like to see these talented Negroes in plays with a voice. for the truth of their own lives.

You see the rehearsals and the plays, and walk among these people, and in some of them you see the experience of the hard years in their faces, you hear it in their stunned and waking voices, and you wonder how long they will be satisfied with themes out of a dead life. Some of the people are dead: their lives have been broken in a failing world, and the end is this: a little security for awhile, something to eat, a room some place, a cheap pair of shoes, or a coat on sale. If the reactionaries succeed in killing the Federal Theatres, how will it be next? The fear before and the fear after: here is a little respite. But the others are alive, and sooner or later they will wake up to the drama they are living. You feel a great patience and expectancy. Many of them have not thought much about why they are on relief. The “depression” is the answer to everything. They do not question the crisis, they do not yet identify themselves with the millions of other disinherited people. They do not yet identify their position with that of a great body of people harassed by the same problems throughout a chaotic world. They are so steeped in the distorted ideas of our traditional culture, created by a class guarding its own interests at the expense of the majority, that their thoughts are guided by these ideas instead of by facts. This manner of thinking excludes the truth of our times, and leads to that state of sleep-walking wherein all criticism of the status quo is viewed as false. Hence, the truth becomes subversive, and the less courageous are fearful of recognizing it openly. But the facts are so blatant in the lives of these workers, they cannot long ignore them. Playwrights on the project are writing plays out of the lives of themselves and those around them. Plays are being submitted depicting the misery and wealth, the awakening and decay, the contradictions of a dying form of society. Vitality and strength, humor and excitement, emotion and thought are in these plays. If they are not censored and shelved before the actors have a chance to read them, these actors will find in them an expression and vigor that is their own.

The reactionaries fear the new theatres’ portrayal of their surfeited and decadent minority, and the alive and vigorous themes of the oppressed, stirring with a sense of their right to a decent life. With forced censorship, this minority has set up a violently protective circle around the inside of present-day society, and any healthy new life in the theatre has to fight itself free of this plague. The will to fight here lies mostly in the actors emerging from their malnourished (mental and physical) lethargy to a clear understanding of why they are going through this experience.

One thing they will all tell you: that they hope for and will work hard to develop a permanent Federal Theatre, free of censorship and political corruption.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n06-jun-1936-New-Theatre.pdf