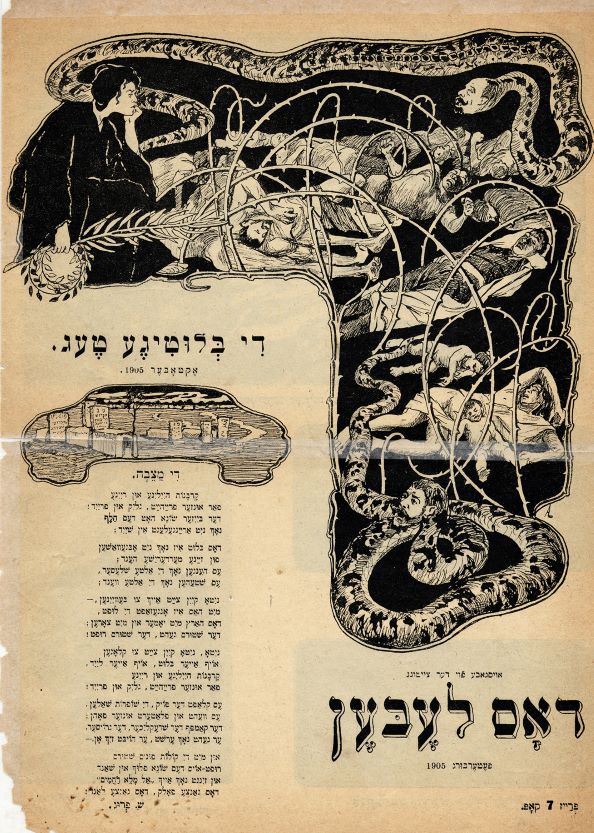

Major review of the history and activity of the Bund written in the midst of the 1905 Revolution. Will be of interest to all students of the Jewish workers’ movement and the Russian revolutions.

‘The Jewish Proletariat in the Russian Revolution’ by L. Ka. from The Worker (New York). Vol 15. No. 17. July 27, 1905.

The Record of the Bund or General Union of Jewish Workingmen of Russia.

The Peculiar Situation of the Russian Jewish Workingmen and the Origin d Growth of Their Socialist Organization–Formed for Economic Struggle, It Soon Enters Political Field–Wonderful Intellectual and Moral Awakening–The Vexed Question of Nationality.

The following article is translated from “Le Movement Socialiste,” where it bears the signature “L. Ka.”

The General Union of Jewish Workingmen of Russia, commonly spoken of as the Bund, is dally becoming better known in Socialist circles and is now attracting the attention of the organized proletariat throughout the world. It has been more difficult for the Bund thus to command attention than for any other Russian Socialist organization, for two reasons: First, been use the publications of the Bund are written in a language known to the Jews only; and next, because until very recently the Jewish masses were considered to be too fanatical, exclusive and downtrodden to be able to participate in the Socialist movement.

The object of this article is to acquaint the readers with the organization of this hitherto unknown Jewish proletariat, whose appearance on the historical stage is surely one of the most important events in the life of the Russian people in the last century.

I.

The repressive measures directed against the Jews at the beginning of the infamous reign of Alexander III were due, according to the explanations in government circles, to the fact that the Jews were rioters and revolutionists. True, there were some of them in the organization of the Narodnaia-Volya (The Will of the People); but at that time the Jewish masses had nothing in common with the revolutionary movement, and those Jews who did participate in it believed the Jewish masses to be impregnable to Socialist ideas.

The brave Narodnaia-Volya went down without attaining its aim, the overthrow of autocracy. A violent reaction set in, the government hoping thereby to prevent a new revolutionary outbreak; and for some time Russia remained cowed and silenced.

Russian revolutionary thought, basing itself upon the experience of the Narodnaia-Volya and the example of the labor movement in the West, arrived at the following conclusion, formulated by Plechanoff: “The revolutionary movement in Russia either will triumph as a labor movement, or it will not triumph at all.” It is not in “the people” in general, and still less in the peasant masses, that the new generation of revolutionists places its hopes, but in the industrial proletariat. It is to the wage-worker that Socialist ideas are preached.

The revolutionary movement sprang up again, drawing in from year-to-year new groups of workingmen and spreading more and more throughout the country. It will not die, as did the Narodnaia-Volya, exhausted by her struggle against absolutism. It will continue to grow, gaining strength in the struggle. It will arouse a great liberating movement among the other classes of the population, and the chains of absolutism will at last fall off under its blows.

Builded Better Than They Knew.

The Jewish Intellectuals, “being confined to the Pale and unable to devote their young energies to the Russian labor movement, began to propagate their ideas among the Jewish proletarians.” (Report of the Bund to the International Congress at Paris in 1900) Not only did they not hope, they did not even intend, to create a Jewish labor movement. They wished only to augment the Russian Socialist forces in general by adding to them certain elements from the Jewish population. They carried on their propaganda in the Russian language, which they had to explain to the Jewish workingmen, who understood it very little, if at all. The agitation was therefore almost confined to those who knew the language and who could consequently apply themselves immediately to the study of history and political economy. Such were the first faltering steps of the Jewish labor movement, for which no one had any great hopes. What were the reasons for this state of affairs? We shall indicate some of them. First of all, the Jewish workingmen had no revolutionary traditions. The middle class, devoted to its religion, timorous, hostile to all new ideas, putting its hope in the God of Israel and the government of the Tsar, constituted then the most numerous and influential class of the Jewish population. The workingmen lived among this middle class and the intellectuals were the more inclined to think that the workmen were imbued with the middle-class spirit since the greater part of the Jewish workingmen were handicraftsmen. At that period, however, only factory and mill hands were regarded as true proletarians, while the artizans were looked upon as future masters, small bourgeois, unfit to furnish reliable elements for the Socialist movement. This was an erroneous opinion, for, with the rapid development of capitalism, the artizan has just as little chance to become a master as the mill hand. But this was the reason why the intellectuals placed no confidence in the laboring masses among the Jews.

Besides, these intellectuals were strangers to the Jewish masses (some of them did not even know the language of the latter) and, nurtured on Russian literature, they felt mostly the suffering of the Russian people towards whom alone they were drawn. It was only owing to the force of circumstances as the report cited above puts it, that they began to carry on Socialist propaganda among the Jewish workingmen.

Unexpected Success.

As a matter of fact, the latter proved to be very susceptible to Socialist teachings. A considerable group of militant workingmen was soon formed at Vilna, which may be called the birthplace of the Jewish labor movement. This success and the closer acquaintance with the mass of workingmen changed the views formerly entertained by the intellectuals. Little by little the latter were confronted with a new problem–the organization of the Jewish proletariat. This could not be solved, however, by ordinary means.

It was Impossible, for example, having in view the organization of the masses, to continue the propaganda in the Russian language which the masses do not understand. Still less was it possible for them to confine themselves to oral propaganda only. Besides, the leaders of the movement thought it impossible to win over the masses by a theoretical propaganda and to develop their class-consciousness outside of the economic struggle. We must begin, they said, by organizing the masses upon the basis of immediate economic demands which will appeal to them most and are easiest to obtain.

Thus the whole policy was changed. A vast agitation in the masses, based on the subject of their immediate interests, was commenced. The workingmen were prompted to organize into secret trade unions and to struggle for the amelioration of their condition–the shortening of the hours of labor, the raising of wages, sanitary conditions in workshops, and so forth. Strikes broke out. The demands of the workingmen being very modest, on the one hand, and the exploitation of the workers very great on the other, the masters conceded at first a few of the demands. This encouraged the workingmen. The number of unions increased rapidly and the strike movement spread to other towns, to Minsk, Bielostok, Brest-Litovsk, Kovno, Warsaw, and elsewhere. Agitation pamphlets in Yiddish appeared more and more frequently. At the end of 1896, the first number of the “Yiddischer Arbeiter” (“The Jewish Workingman”) appeared–printed abroad–and in 1897 a group of workingmen in Vilna began to publish the magazine called “Arbeiter Stimme” (“The Voice of Labor’).

Effect of Socialist Agitation.

The workingmen who participated in this movement detached themselves of their own accord from the middle class and began to live an independent life engrossed in the affairs of the organization and in the various problems arising out of the movement. They not only ceased to be fanatical, but became altogether indifferent to religion which they gradually come to renounce, consciously arriving little by little at the conviction that God is but the creation of Man.

Intellectual wants arose among the masses. They aspired to education and clamored for instruction at the hands of the more enlightened workingmen and intellectuals. The workingmen and women–those of them who participated in the movement–hired teachers out of their meagre wages and spent nights over textbooks. To satisfy this demand there appeared, along with the “underground” pamphlets, a series of popular scientific books in Yiddish. The appearance of this new reader, the workingman, gave rise to a new tendency in the Yiddish literature; there appeared novels and stories describing workingmen’s life; the best works of the Russian literature were translated; the labor song appeared.

The moral standard of the laboring masses also rose to a higher plane; the spirit of solidarity penetrated everyday life; new ideas of woman, of the family, of duty sprang up. The strikers, as the masters called the organized workingmen, lead a fuller, more conscious, more intense, more intellectual life than the middle class or those of the workingmen who still remain under the influence of the latter. The personality of the workingman is asserting itself in the organization and in the struggle. His submissiveness and humility have given place to an aggressive consciousness of his human rights and self-respect. He begins to comprehend more and more fully his solidarity with the proletariat all over the world, of whose movement he has learned in secret meetings and through the channels of underground literature. He observes the revolutionary festivals, the First of May and the First and Eighteenth of March, the assassination of Alexander II.

The government had its eye on the movement from its beginning and persecutions commenced. But this did not retard the movement, which assumed more and more a purely political character. The agitation was carried on in the workshops and in the schools and in the streets. The use of leaflets began. The workingmen began to organize demonstrations on their own initiative, accompanying in crowds those of their comrades who were to be exiled to Siberia, from the prison to the railway station. In spite of the assistance accorded by the government, their masters, the workingmen of various trades succeeded in obtaining twelve and even eleven hours as a maximum workday, including the noonday rest, and a raise of wages. The movement had become a social force.

II.

Formation of the Bund.

Close intercourse between the various cities where the movement developed was maintained from the start, but there was no formal union between them. This was consummated at the end of 1897 at the first convention of the Jewish Socialists when the General Union of Jewish Workingmen In Russia and Poland or, as it is usually called, the Bund (i.e., Union) was founded. A Central Committee was elected whose duty was to direct the entire movement, and local committees were formed in the various cities. The movement assumed still greater proportions, causing the government no little anxiety. The Minister of the Interior entrusted to the gendarmes of Moscow the duty of destroying the organization.

About the middle of 1898 seventy members of the Bund were arrested in one night and the printing establishment of the Central Committee was seized. [Since then the government has never succeeded, in spite of its efforts, in capturing a single central printing office of the Bund offices, too, which turn out tens of thousands of leaflets and circulars in a day.-Translator.] Almost all the lenders of the movement were among those arrested. It was a terrible blow, but the movement had struck such deep roots and its necessity was so profoundly felt that it was impossible to stifle it.

After a few months, a second convention took place; the “Arbeiter Stimme” appeared again, and two new revolutionary organs were created. The strikes, which heretofore used to occur in single shops, began to take in entire trades.

Takes On Political Aspect.

But the purely economic struggle satisfied the masses no longer. The local committees and the Central Committee began to devote themselves particularly to political agitation. The third convention of the Bund, in 1900, recognized the economic struggle only as one of the means calculated to develop the class-consciousness of the workers. The spirit of discontent from now on penetrates the very depth of the laboring masses, and is carried from the cities to the remotest towns. The fermentation spreads and everywhere the workingmen aspire to a higher and freer life. The cautiousness of the earlier times would be fatal now, and the Bund unfurls the banner of Revolution before the entire Jewish proletariat. Every important event in public life is made an occasion for circulating leaflets, in which absolutism is shown in its true light, the fundamental principles of Socialism are explained, and the entire Jewish proletariat is summoned to the struggle for political and economic emancipation. Street demonstrations have become affairs of ordinary occurrence; in cases when it is impossible to organize such demonstrations, political strikes are resorted to. Thus, only recently, such demonstrations and strikes took place in all the towns where the Bund has a good foothold, on the occasion of the massacres of workingmen at Bielostok.

[This answer of the Jewish proletariat to the massacre of Blelostok, made almost simultaneously throughout the territory of the Bund at the suggestion of Its Central Committee, made it clearer than ever what a wonderful mechanism the Jewish proletariat has at its disposal in the Bund. The effectiveness of this mechanism which brings into motion the great masses of Jewish workmen under the trying Russian conditions, were demonstrated again in the January days and the revolutionary period which has followed since; thousands and tens of thousands of proletarians have been quitting work, stopping the entire industrial and public life of their cities, which assume the peculiar aspect of revolution, and have been arranging monster demonstrations which in most cases end in bloody conflicts with the police and the army. It is interesting to note that the universal recognition of the leading part of “The Committee” is by no means confined to the working people, being shared by other classes as well. Storekeepers, on being required by the police to re- open their stores, replied: “The Committee has ordered the stores closed, and will no doubt issue orders to open them;” and they did reopen their stores when they read the circulars of the Committee announcing the end of the strike. The extraordinary alertness and mobility of the entire organisation of the Bund was shown by the special conference which was held in Russia in February of this year (partially reported in The Worker of April 15) for the consideration of the questions raised by the revolutionary events of January. It lasted seven days and adopted a number of decisions as to new methods of revolutionary activity based on the newly gained experience of the few preceding weeks.-Translator.]

From time to time the Bund appeals to the Jewish educated classes, showing them that they have nothing to hope for from the government and urging them to engage in the struggle against autocracy. The revolutionary propaganda penetrates even into the barracks where Socialist writings and leaflets are being distributed.

Ruthless Persecution

The stronger the Bund grows, the more ruthless does the government become toward the Bund and toward the Jews in general. For mere participation in strikes workingmen are exiled to Siberia by hundreds, arrests grew more and more numerous. The Jewish “political,” those who are guilty of political offence–feel that they are being treated more severely than the Gentiles.

In some places the administration resorts to the most infamous form of punishment, whipping. In 1902, twenty-two workingmen were flogged in Vilna for having participated in a May Day demonstration. The governor, Von Wahl, was present in person, counting the lashes and mocking the victims. A few days later an attempt was made upon his life, but he was only slightly wounded. Hirsh Leckert, who made the attempt, was hanged.

Jewish working girls arrested during a demonstration at Libau were entered by the police upon the register of prostitutes. All the Jewish high-school students are regarded as suspicious characters; “they are subjected to injustices of all kinds, are insulted, and on the least provocation are expelled from school without mercy.” The number of Jews allowed to enter universities is greatly reduced. Jewish soldiers are subjected to an exceptional treatment; the military authorities declare that all Jewish soldiers are rioters, watch them as criminals and incite the Christian soldiers against them.

The government attempted to demoralize the Jewish laboring masses by offering, through special agents under the direction of Zubatov, to support them in their economic demands if they would abandon their political struggle. But this attempt failed completely; the masses remain faithfully attached to the Bund.

Massacres and Self-Defense.

Unable to accomplish Its aim either by arrests and deportation, or by trickery, the government decided to resort to the most desperate means; it incited the so-called “pogroms”, or massacres of Jews. Along with the traditional outcry, “Death to the Jews!” the additional cry of “Death to the Social Democrats!” could be heard at Kishinev and at other places where these massacres occurred. In the various towns when an outbreak is feared, the governors usually state to Jewish delegations that these massacres are a response to the Jewish labor movement. However, the blood of the Kishinev victims only intensified the hatred which the Jewish proletariat feels against Tsarism and aroused the entire world against the latter. [The answer of the Bund to the governmental policy of massacres was the creation of “Committees of Self-Defense” according to a decision adopted at the fifth convention of the organization. The first test of this new device of the Bund took place at the time of the Gomel massacre in 1903. It was only due to the armed resistance rendered by the Jewish workmen and partly by members of other classes of the population that the Gomel massacre did not assume the horrible proportions of the Kishineff affair. That the intended massacres which were being actively urged by the police did not materialize in several cities was also due to this new organization which, in a certain sense, marks a new era in the history of the Jewish people, who have been trained by thousands of years of persecution to servile submission and cowardice. Of the devotion and heroism of the members of “Self-Defense”, their struggle with the organized police gangs in the recent Zhitomir massacre bears eloquent testimony.- Translator.]

The Jewish capitalists, large and small, are opposed to the Bund, and they have more than once helped the government in its struggle against it. Of course the capitalists would like to see the “Pale” and the exceptional laws abolished: but they would like to attain this end not by a struggle against the government, but by servility to it. The Zionists are also outspoken enemies of the Bund because it distracts the Jewish masses from their “historical mission”, which is the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine–or somewhere else. The activity of the Zionists who dissuade the workingmen from participating in the struggle against absolutism and try to arouse in them the spirit of racial exclusiveness is most pernicious to the Socialist movement and the Bund incessantly combats them.

At present the Bund represents a powerful and united organization which the government has failed to break up. It is pre-eminently a proletarian organization, imbued with a purely Socialist spirit and linked very closely with the laboring masses. It is not the committees which compose the Bund, but the rank and file of the Jewish proletariat itself. In order to give a clearer idea of its activities we shall cite a few figures from its report: to the International Congress at Amsterdam.

The Bund’s Activities.

The number of workingmen belonging to the organization is no less than 20,000. During the year from June, 1903, to July, 1904, there were held 418 meetings1 (not counting the ordinary meetings of committees and groups), forty-five demonstrations, forty-one political strikes, and 109 strikes with over 24,000 strikers. On the First of May the Bund organized sixty-seven mass meetings and thirty-seven political strikes. It published twenty-three proclamations with reference to the “pogroms” and sixteen about the war. Altogether 305 proclamations were issued during the year, the total number of copies of 241 of them amounting to 688,000. [The May Day proclamation of the Central Committee was distributed in 1902 in 20,000 copies; 1003, in 70,000 copies; 1904, in 90,000 copies; 1903, in 130,000 copies.-Translator.] In Russia it publishes two organs of the Central Committee–the “Arbeiter Stimme” and “Der Bund”–besides several papers issued by the local. Those published abroad are the “Jüdischer Arbeiter” and a weekly, “Poslednia Izvestia” (“The Latest News”). It recently began the publication of another review, “Vestnik Bunda,” in the Russian language. Since its establishment, the Bund has published a great number of pamphlets, such as “The Communist Manifesto,” Lassalle’s “What Is a Constitution?” Kautsky’s “The Erfurt Program” and “The Day After the Revolution.” Lafargue’s “The Religion of Capital,” a series of biographies of famous revolutionists, several pamphlets against Zionism and others.

The number of persons arrested during the year named for having participated in the Bund’s activities was 4,407.

These figures speak for themselves and need no comment. The reader is only reminded of the fact that meetings, demonstrations, Socialist publications, are absolutely prohibited in Russia.

The Question of Nationality.

In the early days of the labor movement among the Jews the opinion prevailed that the Jewish workingman does not suffer from the fact of his being a Jew, but that all his suffering is due to his being a workingman exploited by capital. But this opinion was too much at variance with actual facts to be entertained long. On the contrary, his peculiar position, resulting from legal discrimination against his race by the government, soon became one of the topics of agitation. And the more the movement grew, the more keenly the Jewish workingmen felt the yoke of these exceptional laws, the more did the masses realize their humiliation, and it became clear what a powerful factor in the emancipation of the Jews this movement could be come. When the Bund was formed in 1897 the main reason given for the existence of an exclusively Jewish organization was that the exceptional laws imposed upon the Jewish proletariat a special problem. True, not only all the proletarian organizations, but also those of the Liberal opposition, declare themselves in favor of equal rights to all. But no other organization would be able to give so much attention and to devote so much time to the struggle against this exceptional and humiliating position of the Jews, nor could it arouse in the latter a sense of civic dignity which they almost completely lacked with any chance of success such as has crowned the efforts of a Jewish proletarian organization like the Bund.

The demand for equal rights still remains the most essential point in the practical activity of the Bund. But it has ceased to suffice from the standpoint of principles. Little by little the national question assumed great prominence. This was due, as is explained in one of the pamphlets of the Bund to the following causes: The Jewish proletariat lives among other oppressed nationalities–the Poles, the Lithuanians, and others–each of which has a national platform. Some of them try to win the Jewish workingman over to their side: there are some bourgeois parties which also have national planks in their platform and are trying in their turn to win over the Jewish proletariat to their side.

Under such circumstances it became impossible to keep out the national question. The Bund was compelled to Jake a stand upon it, since otherwise the capitalist parties might gain influence over the Jewish proletariat. But the problem was not easy to solve. since many Socialists think that the Jews are not a nation. After prolonged groping and hesitation the Bund finally adopted the following resolution at its fourth convention:

“Whereas. According to Socialist principles it is not only inadmissible that one class should oppress another, or that the governments should oppress the citizens, but also that one nation should oppress another nation, the Convention declares that a state like Russia, which is composed of a number of different nationalities, should In future be organized on federative principles, each nation enjoying complete autonomy, irrespective of the territory occupied by it.” The Convention declared, besides, “that the idea of nationality is also applicable to the Jewish people.” At the same time however, the Convention did not consider the time opportune for including the demands for national autonomy of the Jews with the other demands and confined Itself, therefore, to a declaration for the abolition of exceptional legislation against the Jews.

Thus the line of action of the Bund has not been changed and the resolution upon the national question has only a theoretical character.2

A Source of Disagreement.

The resolution has, however, provoked a good deal of protest on the part of many Russian Social Democrats grouped around the “Iskra” who accused the Bund of having become nationalistic or Chauvinistic. We shall not dwell here upon the differences between “Iskra” and the Bund, constituting a regrettable page in the history of Russian Socialism. Suffice it to say that the discussion of the issue led “Iskra” to express its doubts as to the usefulness of maintaining a special organization of the Jewish proletariat, and many of its partizans considered the very existence of the Bund an anomaly.

At the second convention of the Social Democratic Party of Russia,3 which took place in the latter part of 1903. and which was expected to consummate the organization of the Party, the Bund proposed a regulation which would guarantee it the necessary freedom of action. This proposition, which would not have affected the position of the Bund within the party, was defeated. Its delegates thereupon withdrew from the convention and since then the Bund has ceased to belong to the Party.

[That the Bund was right in its attitude was demonstrated immediately following the adjournment of the second convention of the Party, which split in two as a result of the new conspiratory form of organization it adopted. This split has paralyzed the activity of the party for the last two years. The two years’ experience has not been wasted, however, and one may hope, using the words of one of the Russian comrades, (V. Akimov, “A Contribution to the History of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party: 1905) that “the Bund will witness the fifth stage of our development, when the Russian movement will rise to the level, now reached by the movement of the Jewish workmen, when the just demands of the Bund will be satisfied by our Party.”-Translator.]

This is not the place to discuss whether the Bund was right in adopting the resolution with reference to national autonomy. In free Russia, at some future convention of all Russian Socialists, the national question will be raised again and the Bund as well as the other national organizations will submit to the common decision to believe that a separate organization of the Jewish proletariat is actually useless and to desire the disappearance of the Bund is a grave error. The local committees of the Party would never be able to do what the Bund has done among the Jewish proletariat. The civilizing influence of the Bund upon the Jewish masses, the strong ties which unite it with the Jewish proletariat, make the existence of the Bund indispensable and call for freedom of action on its part. And in the interest of the struggle against Antisemitism, all Socialists must conduct. But it is important that the activity of the Bund, the activity of the Jewish proletariat, be well marked in the Russian revolutionary movement. It is necessary “that the emancipation of the Jews be not an act of mercy towards the humble, not even an act of justice from the standpoint of Socialist principles, but the result of the part which the Jewish proletariat plays and will play in the liberating movement, the immediate object of which is the overthrow of absolutism.”

Unity In Action.

It should be added that the rupture between the Bund and the Social Democratic Party has by no means prevented the former from acting in perfect harmony with the local committees of the latter during the recent events. [The Bund has long been at work in an attempt to bring about a working agreement between the different Social Democratic organizations and thereby prepare the ground for a complete union of the proletariat of all Russia. These efforts have lately borne first fruit: in January of this year, on the initiative of the Central Committee of the Bund, a conference of Social Democratic organizations took place in Russia (partially reported in The Worker of April 8), at which a number of questions relating to tactics and organization were discussed. The following organizations were represented in the conference: The Central Committees of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, of the Bund, of the Lettish Social Democratic Labor Party, and of the Revolutionary Party of Little Russia. The resolutions adopted by that conference, were also ratified by the following organizations which by accident could not be represented: The Social Democratic Party of Poland and Lithuania, the Polish Party “Proletariat,” and the Armenian Social Democratic Labor Organization.-Translator.]

NOTES

1. The number of people who attended those meetings exceeded 1,000 persons in twelve cases.

2. To adopting this resolution, the Bund was guided to some extent by the resolution on the same question which the Socialist Party of Austria adopted at its Brian convention in 1897.

3. The Party was organized, in 1898, but Its Central Committee was arrested soon after its election, and could not then be reconstituted. The party thus censed to exist, although the local committees and the Bund continued to consider themselves as organizations of the party. In a proclamation on the subject of recent events, 25.000 copies of which were published in Yiddish, Russian and Polish, the Bund appeals for the struggle against absolutism by means of a general strike followed by an armed Insurrection. “Do not forget that life in prison is more terrible than death in the struggle. Let all streets be converted into battlefields. Let us all give our blood for the rights of man and citizen.” The following are the demands enumerated in that proclamation:

1. The convocation of a Political Assembly elected by universal suffrage, without dis tinction of sex, religion, or nationality.

2. Abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a democratic republic.

3. An eight-hour day in factories, mills, shops, stores, offices, etc.

4. Inviolability of person and of the home.

5. Liberty of conscience; free press; freedom of speech; right to organize unions, strikes, associations.

6. Equal civil and political rights for all nationalities. The right of the latter to Instruction In their own languages and to their use in public life.

7. Immediate release of all exiles and persons Imprisoned for religious and political offenses.

8. Immediate cessation of the war. The abolition of the standing army and the creation of a national militia.

The Worker, and its predecessor The People, emerged from the 1899 split in the Socialist Labor Party of America led by Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit, who published their own edition of the SLP’s paper in Springfield, Massachusetts. Their ‘The People’ had the same banner, format, and numbering as their rival De Leon’s. The new group emerged as the Social Democratic Party and with a Chicago group of the same name these two Social Democratic Parties would become the Socialist Party of America at a 1901 conference. That same year the paper’s name was changed from The People to The Worker with publishing moved to New York City. The Worker continued as a weekly until December 1908 when it was folded into the socialist daily, The New York Call.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-the-worker/050722-worker-v15n17.pdf