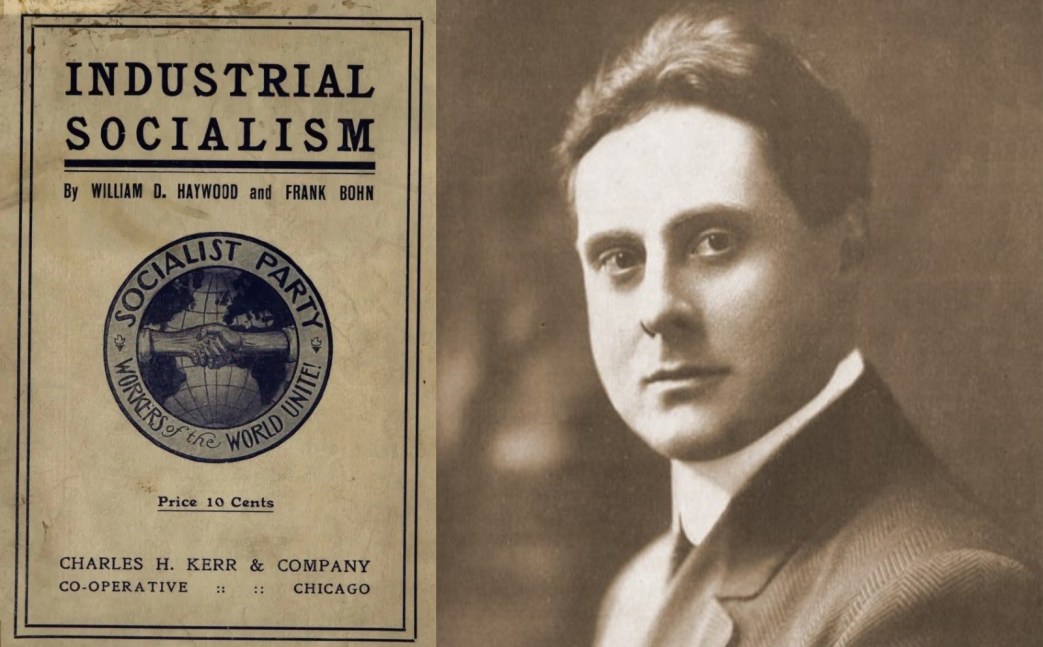

In response to the growth of a left-wing in the Socialist Party, personified by Haywood’s resounding 1911 election to the party’s National Executive Committee, the right-wing began a concerted campaign against the left. At the end of 1912’s National Conference “Article 2, Section 6” was added to the party constitution demanding the expulsion of any member who “advocates crime, sabotage or other methods of violence.” Charged with its violation, Haywood was recalled from the N.E.C. in February, 1913. Many thousands of activists would leave the S.P. in that period, losing 20% of its membership that year alone. Haywood would leave S.P. activity and take over from Vincent St. John as General Secretary-Treasurer of the I.W.W. In that period Frank Bohn was a close collaborator with Haywood, co-author of their ‘Industrial Socialism’ manifesto, who helped organize his N.E.C. run. He also sat on the ISR board for which he wrote this valuable editorial for understanding the crisis.

‘The State of the Party’ by Frank Bohn from International Socialist Review. Vol. 14 No. 4. October, 1913.

THE Socialist party is absolutely indestructible—which fact furnishes a perfectly safe but far from satisfying mental refuge in times like these. In every country of a sufficient degree of capitalist development, the Socialist party appears as naturally as the steam engine and the automobile. For syndicalists, anarchists and old party politicians to talk of its decay or permanent setback is like the horse, the ox and the ass resolving that the world should go back to the days when they constituted the fundamental powers of transportation. Especially in the life of Great Britain, America and Australasia, is political action of the workers a necessary accompanying form of the class struggle. The working class in these countries have always voted—thinking that they were voting to better their conditions of life. That they have failed in their object has been due to their lack of knowledge and of political and of industrial organization. Even so, who can doubt that the working class vote has protected their fundamental civil rights— their right to assemble, to organize, to publish and to speak their minds with a degree of freedom which makes the abnegation thereof at this time a strange and startling matter. In every country the Socialist party has grown steadily. Strange, indeed, must be the cause which can produce a break in the upsweeping curve of Socialist progress anywhere.

The fact that during the past twelve months we have lost one-fourth of our membership and seen our activity decrease at least 75 per cent would be amazing were the cause thereof not patent to all. We would be lacking in both intelligence and loyalty to the party did we not analyze the forces and factors at work and suggest needed remedies.

The cause of this loss is not ephemeral or temporary. It is due to deep-seated forces of disruption within the party—forces which must cease to act before the tide can turn toward better things. In the August issue of The New Review, the editor of that valuable periodical, after pointing to the colossal loss in membership suffered by the party, goes on-to analyze, in language none too extreme, the main cause of the difficulty. Without hesitancy he puts his finger on Section 6, Article 2. Every member of the party should read this editorial entire. We can quote but briefly from it here. After emphasizing the weak and contradictory character of this clause, Comrade Simpson continues:

“But the worst effect of the whole business was that now, for the first time in the history of the Socialist Party, a basis was laid for inquisitorial procedure against members who happen to be unpopular with the powers that be in the party. Hitherto Socialists had differed among themselves as to the relative value of political action (in the narrow, parliamentary sense) and industrial action, but believing in both forms of action they stayed in the party and worked together for the common cause. They even ventured to differ among themselves as to the profound world-shaking problem of sabotage. But now all was to be changed. Henceforth every party member of somewhat vivid imagination and loose tongue could be haled before the inquisitorial tribunal. Did he or did he not say this or that thing? If he did, he stands expelled for heresy. And this in a party that rightly boasts of. being not a society of the elect, but of being, or aiming to become, the party of the working masses of the nation, the political expression of the class movement on the proletariat!

***

“Expulsion of individual members, and even of entire branches and locals, has become the order of the day. In the State of Washington the state organization was split wide open, the reformist element there going out of the party, forming an independent organization, and adopting a platform in which the words ‘working class’ and ‘class struggle’ are carefully shunned “The fact is that in our factional embitterment we appear to have forgotten, not only our common Socialist principles and aims, but even the rules of ordinary intercourse and the commonest democracy. In our platform we demand proportional representation, but in our internal party practice we find an unholy joy in being able to suppress the minority utterly and completely. Wherever one faction happens to be in power, it systematically excludes the members of the other faction from the party counsels, the management of the press, the selection of speakers, etc.”

Quoting the astounding conception of the editor of that “sheep in wolves’ clothing,” the Metropolitan Magazine, to the effect that Haywood’s expulsion from the N.E.C. “clears the way for a better understanding between the progressives and the Socialists,” the editorial concludes with the following suggestion:

“Surely, a halt must be called to such tactics, as destructive and disruptive as they are disreputable. The Socialist party cannot thrive upon, and should not tolerate, the methods of boss and machine rule which prevail in the old parties. The S.L.P. has shown us where boss methods lead to in the Socialist movement. Even the Republican party, inured to machine rule and reeking with corruption, has recently afforded the spectacle of revolt against: the excessive employment of the ‘steam roller.’ The appalling loss in membership reported by the national! office should serve to call us back to our senses. To persist in our present ways is to court destruction for the party and to hamper and retard the progress of Socialism on this continent.”

SECTION 6, ARTICLE II.

Section 6, Article II is a living, standing insult to the whole American movement. At Indianapolis, in May, 1912, I sat in the balcony of Tomlinson Hall and saw the majority of the convention systematically worked into a fever of excitement, bitterness and fear of something which did not exist, until the time was ripe to write the clause into the party law. During the thirteen years in which it has been my privilege to work in the Socialist movement, I have never heard a capitalist politician or even the most bitter Roman Catholic clerical opponent of Socialism say that we were criminals. It remained for the Indianapolis convention of the party itself to declare to the world that our ranks were so infested. When the vote was passed the hilarious leaders of the majority started to sing the “Marseillaise’—thus degrading our sacred anthem into a means of jollification to signalize their victory in a party brawl. And this deed was accomplished through the help of scores whose services to the movement I had admired and whose confidence and respect I thought I had, until then, enjoyed. Ninety delegates and hundreds of comrades sitting in the balconies left Tomlinson Hall that afternoon feeling the party had reached its very lowest possible state of moral degradation. The forces of disruption had at last created for the time being an unbridgeable chasm between two groups within the party. Only a firm faith in the fundamental principles of the party and in the moral soundness of the thousands of members of the rank and file who were thus led into the belief that some of us were criminals, have, during the past year, served to keep us in the party and at work.

SOME DEFINITIONS.

A criminal is one who has committed a heinous offense against the well-being of the state, for which the state provides juridical means of accusation and a heavy penalty in case of conviction. It is for the state, not for individuals, to define this word. To the British government every advocate of American independence during the Revolutionary war was a criminal. To the slaveocracy in control of the government in 1850 every citizen who refused to help the federal government to catch slaves was a criminal. Section 6, Article II binds the Socialist party to accept the definitions of crime prescribed by the legislatures and courts of capitalism. When that clause was passed the Socialist party thereby temporarily resigned its revolutionary position and humbly cringed before the powers that be.

THE POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE OF SABOTAGE.

When Section 6 was under discussion, Delegate Tom Hickey of Texas declared that he knew of few delegates who were capable of correctly pronouncing the word ‘sabotage,’ and to think of delegates being able to act intelligently upon something they did not understand was ridiculous. Comrade Hickey was quite right. Sabotage as a means of accomplishing the revolution! In all my traveling for the party I have never heard any member anywhere remotely suggest that sabotage could be used in any possible way for the purpose of accomplishing the revolution. For any one to suggest such a possibility would simply be to expose a degree of ignorance so great as to make him absolutely harmless. Sabotage is used everywhere, in season and unorganized, to secure definite immediate ends. That is all.

Now as regards the negative of the sabotage argument. Tell a revolutionist who has lost a dozen jobs, broken with half his friends and quarreled with his wife in order to engage in the Socialist movement, that he must not use a certain word and then watch and see what he does. He will cry it from the housetops. He will din it into the ears of those who tried to muzzle him until they wish they had left him in peace. That is just what has happened during the past year. After the Indianapolis convention there were revolutionary Socialist papers which advocated sabotage in screaming headlines to the workers in general. I.W.W. soap-boxers began to talk of nothing but sabotage. I have heard a street speaker spend an hour telling clerks how to spoil paint by putting chemicals in it while painting. Thousands in the party who would never have heard the word had it been left out of the party constitution, began to grow excited and to argue and quarrel about sabotage. This was but the beginning of the terrible price our party was to pay for that acme of official stupidities, Section 6, Article II.

EXPULSIONS AND DESERTIONS.

In order to found this argument entirely upon facts I shall here refer to such only as have fallen beneath my personal observation. During the year I have traveled and mixed with the membership from New York to San Francisco. Since we are talking about crimes, the worst crime I know of is a cowardly refusal to face facts which are troublesome and disappointing.

Elyria, Ohio, is an industrial town of fifteen thousand people. Two years ago its local of over a hundred members was the most active organization of its size with which I have ever come in contact. It now numbers just five dues-paying members. In Chicago, Ill., following the death of the Daily Socialist, the English-speaking membership has fallen to 1,500. Years ago Chicago often received more than 1,500 applications for membership within a period of six months. In Chicago the foreign speaking organizations, which have escaped this disruption, now outnumber the English-speaking branches by about 600. I am told by veterans here in Chicago that the local is today conducting less work of propaganda and education than was accomplished by the old S.L.P. before the split in 1899.

Detroit, Mich., now has 50,000 workers in the automobile industry alone. It is one of the ripest fields for sound Socialist progress in the whole world. On the occasion of my visit to that local last June I found seven members present at the meeting of its main branch. The next night at a meeting of an I.W.W. local I found at least a hundred active young men who had left the Socialist Party and joined the I.W.W. When I labored with some of them in order to point out the error in leaving the Socialist Party, they replied to me with jests about Section 6, Article II.

Local San Francisco, Cal., so greatly feared my presence among its membership that it refused to conduct the Lyceum Course because I was one of the lecturers. Its membership had reduced to a shadow of what it was several years ago and seemed to be wholly inactive.

The great state of Illinois has not now a single Socialist organizer or lecturer in the field.

The whole situation is by no means statistically summed up by citation of the numbers of members lost. For the first eight months of 1912 the average number of dues-paying members was 118,519. For the first eight months of 1913 the member ship averaged 93,327, showing a loss of more than 21 per cent. But the activity of the party has decreased more than fifty per cent. The life spring of our activity is enthusiasm for our cause. Nothing so poisons and dries that spring as factional bitterness and conflict. During the year just past hardly a local and state organization has escaped disruption. During this year we should at least have held our membership even, as we did during the postelection years of 1905 and 1909. Furthermore, let it not be overlooked that the members lost have not been new and untried recruits. They have been largely the most active and valuable workers in the cause.

PARTY UNITY.

A member’s degree of loyalty to the party and to the cause is indicated always by his willingness to forget differences, great and small, with his comrades, in united service of the movement as a whole. As soon as a member spends more time in fighting his comrades than in fighting the common enemy he becomes a negative force and is worse than worthless to the organization. When factional troubles are of long standing their worst effect is to embitter the members against one another and thus destroy their usefulness. During the past year many thousands of members have so far forgotten the primary purpose of our movement that it is questionable whether they will ever again be valuable factors in the struggle. A man who works ten hours a day at a machine or a woman who toils from dawn until dark in the kitchen and the nursery find that bitter words soon “get on their nerves.” Either they remain away from meetings or they come to find a certain joy in “putting it over the other fellow.” Thus a local falls from a membership of a hundred good-natured, active workers, to a score of cantankerous, meanspirited factionalists. Such has in many cases been the course of our locals during the past year.

When the convention of 1912 met at Indianapolis the party had not been greatly injured by any of the factional controversies which had taken place. By far the greater majority of the membership or the delegates took side permanently in none of these conflicts. The opening days of the convention were marked by a fineness of spirit which greatly encouraged every one present. I recall an incident which I shall always remember as indicative of the proper spirit on such occasions. A young delegate came up to Haywood in a state of considerable excitement and urged that the fight be pressed against those who disagreed with the policies which Haywood and others advocated. “Let us compromise with our friends and fight our real enemies,” answered Haywood.

This was the spirit which the revolutionary-minority exhibited throughout the convention. Specifically was it manifested in the discussion of the labor union resolution, both by the committee and on the convention floor. I have suggested that the depths were reached during and after the passage of Section 6, Article 2. The heights of party fraternity and unity were attained during the discussion of our attitude toward labor unions. The unanimous report of the committee was unanimously endorsed by the convention. That was the time to sing the “Marseillaise.” But—

“We will get them tomorrow,” said certain delegates as they left the hall—delegates who had not dared by voice or vote to break the unanimity with which the resolution on labor unions was received and adopted. “Tomorrow” brought with it the poisonous exhalations which still weaken the body and trouble the spirit of the party.

The fact that such action could result in such a travesty which in turn could prove so ruinous to our party is in a sense merely proof of our untrained and unwashed greenness. The lack of Socialist education which makes it still possible for a few Socialist leaders to lead us into the mire and leave us there is a condition which it will take much time and labor to improve. And this work of education must be accompanied by a finer spirit and a higher idealism than has hitherto marked the relations of any of us within the party. The rack and the thumb-screw of inquisitorial procedure have been dragged out of the fourteenth century to be used by factions in the Socialist Party of the United States, not because the membership relished that sort of thing, but because the majority of the membership do not know just what they wish to have done nor how properly to go about doing anything of a constructive nature.

Every delegate who voted for Section 6, Clause II, to whom I have spoken declares most positively that he privately believes in sabotage and that upon reflection he realizes fully that there are no “criminals” in the party. They were led to do what they did on that evil day by their entire lack of preparation to hurriedly face a condition which they did not understand. But for those who were made to suffer for this muddleheadedness to desert the party can only work harm and not good. Running away from a fight because our comrades do not wish to keep step with us in as much desertion as fleeing from the face of the enemy. A member who lacks either the intelligence or the loyalty to be a good loser in the counsels of the party surely lacks the will power to be anything positive at all, not to speak of living consistently the life of a revolutionist.

LET ME SUGGEST.

To the thousands of comrades whom I have met in all parts of the country and whom I have found to be in agreement with myself as regards party policies, let me make the following suggestion: Many of you have left the party. Many more of you have become inactive. A very great many have already come to doubt or are already seriously doubting the efficacy of working class political action in its entirety. Do not permit the circumstances we have described to drive you into this fallacious and inutile position. The destruction of the Socialist political movement in this country was prophesied in 1899, in 1904, in 1905 and in 1910. It did not happen at any of those times. It won’t happen now. Parties in the United States are not made like fresh bread, every morning. The Socialist Party is just ourselves—the twenty thousand who do the work, the 87,000 who paid dues in August—the nine hundred thousand who voted in 1912—the three millions in this country who say to all the world that they are Socialists. We are what we are. If you wish to see growth toward better things within and without, stay with the fight and help build this movement into something better than it is. If sixty years ago the handful of Socialists could live and die keeping the fires burning, you are a pretty poor kind of a successor to them if you lose hope today.

For the time being forget Section 6, Article II, and the day will come when those who passed it, realizing their shame and disgrace, will vote to repeal it. Let me confess here that I have pitied those responsible for it and have wasted not a single moment in hating them. However wrong they were, their error is not one-tenth as great as that of the member who deserts the standards under fire. Let us purge ourselves of every sentiment except that of burning zeal for a cause whose heart’s center can never be touched by individual error. Remember that those who do the most work in the party will eventually control its counsels.

Factionalism lays hold of the ignorant member and keeps him ignorant. It seizes upon the weak man and turns his weakness into downright meanness. No man or woman can long continue engaged in internecine quarrels and come out with mind unscathed. Let us have an end of it.

FRANK BOHN

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v14n04-oct-1913-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf