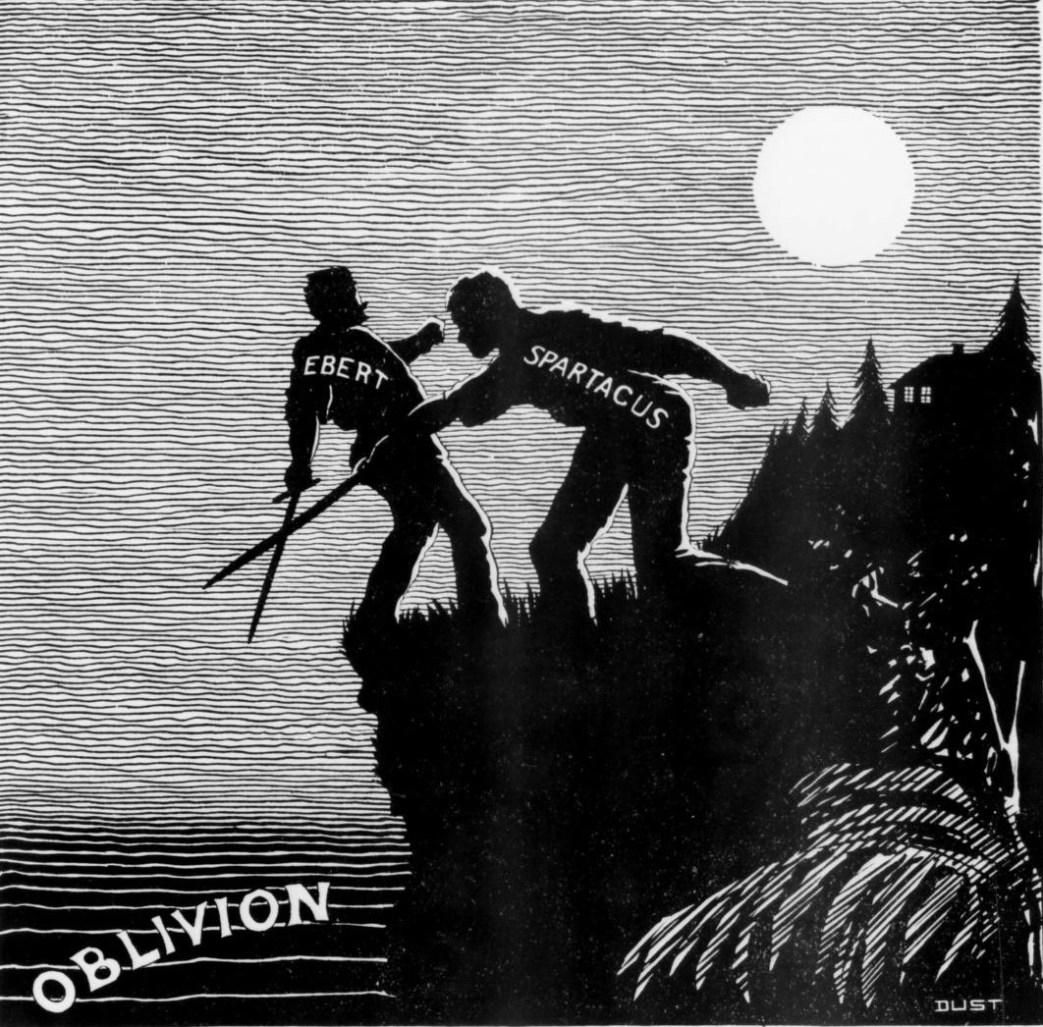

To commemorate this weeks anniversary of January, 1919’s Spartacist Rising here is a forgotten classic; Robert Minor’s gripping first-person narrative of the doomed revolt. After visiting Soviet Russia, revolutionary journalist and master illustrator Robert Minor found himself in Berlin during the German Revolution. There from December, 1918 through the Spartacist revolt, its crushing, and murder of its leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. Minor himself would be arrested for spreading ‘treasonous propaganda’. As a partizan, but also an outsider, Minor produced a detailed and observant account adding brilliant drawings of protagonists. It well deserves a place in the canon on the German Revolution. Part one below, part two soon to follow.

‘The Spartacide Insurrection: Part One’ by Robert Minor from The Liberator. Vol. 2 No. 9. September, 1919.

“ACH, so-o-o! Ganz Schoen!” said the first German soldier I met, as I came through on a prisoner’s train out of Russia. That, with a broad grin of delighted welcome is all that I ever found of German national feeling against Americans, except–

In Vilna it was necessary to visit the German “Eisenbahn Direktion,” where a stiff blond officer emitted a ceaseless flow of German invective upon the “low-down Russian Jews” who waited in line for permits to travel on the railroad. “Weg! Weg!” (Away! Away!) spat the officer. “Unmo-o-o-o-o-e-glig,” he drawled with acid pleasure in the power to refuse. “What you need is to have discipline put into you…Get out of here, you! Weg! Weg!…No permit for you!” he sputtered away automatically, stamping a permit for this man, throwing the application paper back into the face of that one.

Suddenly he caught sight of my fur cap and Russian-looking beard above the heads of the crowd. His face twisted with astonishment and convulsed with rage. He shrieked: “TAKE OFF THAT CAP!” I couldn’t resist the temptation of pretending not to understand. He trembled, and snorted. “Take off that cap, I tell you! Mein Gott! Can you not understand plain German? Take off that cap!”

I allowed a long-bearded patriarch to whisper to me in Russian that one is forced to take off one’s hat in the office of a German “goy,” and then I removed the cap, lying in broken German to the effect that I hadn’t understood. When it came my turn and the officer learned I was an American, his rage was increased by the multiple of wounded pride. In a voice that tried to do the honors for his fatherland, he informed me that “Germans do not love Americans any better than the Bolsheviks do, and the Bolsheviks shoot Americans.” Every German I have since met has smiled upon me because I was an American, but that one kept me waiting two days, just to show that he could, in that strangest of towns–the “back home” of so much of our New York East Side, including Abraham Cahan of the Jewish Daily “Forward.” During my exile in Vilna, I learned what had put the German officer in such a cross mood: most of his soldiers had neglected their rightful superiors to attend the fascinating meetings of the workmen’s soviets, which were organizing to “take over the town as soon as the Germans should be driven out.”

On the train to Berlin, the soldiers spontaneously selected one of themselves to occupy my first-class seat, explaining that the mere fact that I could buy a first-class ticket did not entitle me to any class privileges. They didn’t know what a privilege it was to me to hear them say it. But one simple fellow didn’t get the spirit of it, and commenced triumphantly to rail at me as a Jew. I got angry and thundered at him a lecture. “Suppose I am a Jew,” I said. “What of it? The spirit of your talk is what made the war and caused ten million murders. Haven’t you got enough of that? There are no Jews and no Germans, no Englishmen and no Frenchmen—there are only men. You have no business to call anyone ‘Jew,’ but only ‘man.’ However, I am not a Jew. I am an American, if you want to make distinctions. But I don’t call you Germans; I call you brothers.” The debate went to me by unanimous consent, and when we reached Berlin the soldier called me “thou” as he handed me my broken Russian tea-kettle which he had sat upon while he thought I was a Jew.

***

The incoming train was met by a distribution of circulars pleading with the soldiers not to revolt. Berlin was the same old Berlin. I could scarcely notice a difference in the five years since I’d been there, except the iron spring tires on the automobiles and the flaring posters to warn the proletariat against the one great sin–Bolshevism.

***

Coincidence is a persistent clown. In 1914 I had lodged in a little hotel at number 114 Wilhelmstrasse. Upon this return in December, 1918, I searched out the same hotel, where I found a sign reading: “Office of the Rote Fahne” (The Red Flag).

Tall, gaunt Karl Liebknecht was there. His face bore traces of prison. An impression stole into me, and frightened me, that he had been weakened in body and spirit by the stone and iron. Astonishingly unforceful, sounded the voice of the man whose courage had shaken a world.

While Liebknecht explained that he was very busy, a messenger came to say: “The Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils is about to abdicate to a constituent assembly.” “I must go quickly,” said Liebknecht; “come with me if you wish to talk,” and he and I and another man hurried down to the Abgeordneten Haus a few blocks distant. In speech after speech, the Majority Socialist leaders exhorted the delegates to submit to the Bourgeois order of things. Only in the uncompromising honor and democracy of President Wilson, they said, Could Germany place her faith; the workers must not anger the Entente and American governments by taking up the proscribed Bolshevism, and a Russian alliance must be scrupulously avoided lest it lose for Germany the chance of life which had been promised her through Mr. Wilson.

Gradually it dawned upon me that the hall was full of “phoney” delegates. The “workers’ delegates” were largely superintendents and foremen, and the “soldiers” were officers. The German bourgeois are clever and quick. Knowing that the danger of revolution lay in the inevitable forming of workers and soldiers’ councils, the bourgeoisie, through the Majority Socialist Party, had taken care quickly to form “soviets” with a membership chosen by itself, before such things could spring up naturally with revolutionary membership.

So, in this congress the Spartakists, and such Independents as had their courage with them, were talking to a stone wall. On the tired face of Liebknecht I read the hopelessness of it. “Soviets?” Is that name, too, now stolen from the ever-robbed proletariat? Macchiavellian politics has never received a greater contribution than from the German bourgeoisie since the abdication of the Kaiser.

“All power to the Soviets!” was the planned and only reliable battle-cry of Liebknecht. “Very well,” was the cool reply of the speakers for the bourgeoisie, “all power to decide Germany’s fate shall rest with the Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Soviets (the membership of which we have attended to). What are you going to do about it? Do you really mean ‘all power to the Workers and Soldiers’ Soviets,’ or do you mean ‘all power to Liebknecht’? The Soviet Congress decides to have a constituent assembly. We abide by the decision. Do you?”

“Peace!” shouted Liebknecht, as Lenin had shouted. “Certainly, peace,” said the bourgeoisie. “Mr. Wilson will sign peace only with a democratic Germany, which means a constituent assembly. Let us have no fighting.”

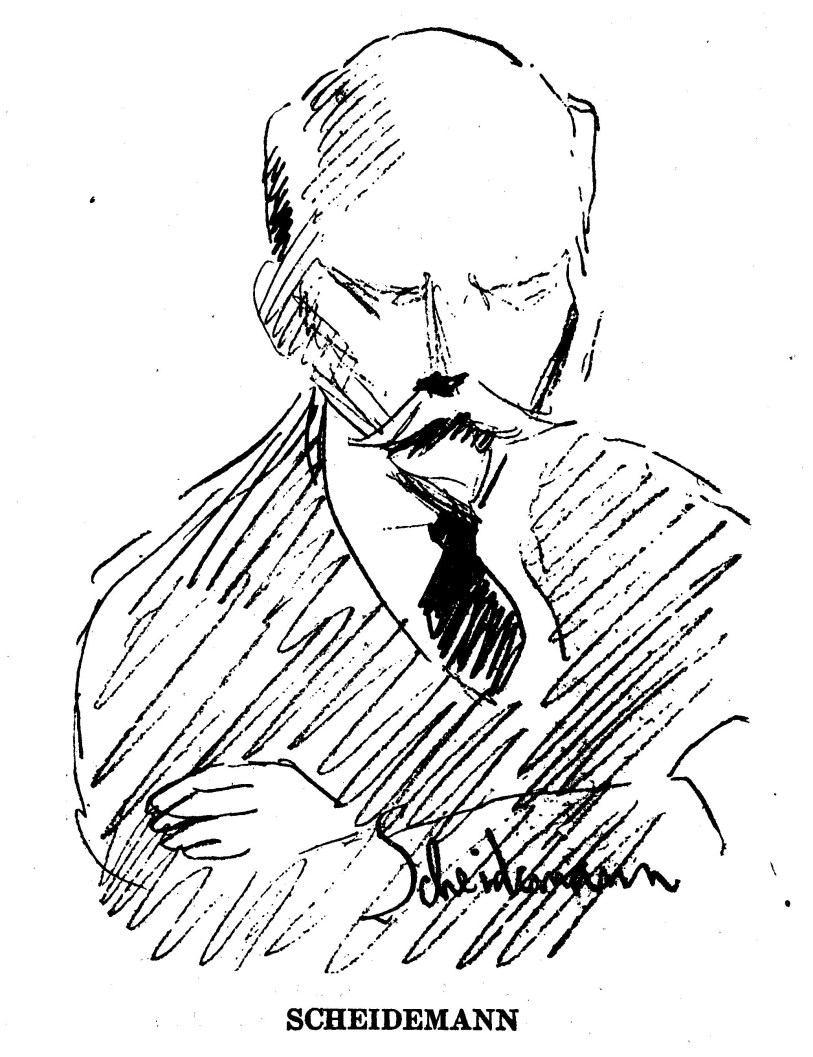

“Socialism!” shouted Liebknecht. “Yes, Socialism,” said the bourgeoisie, through Scheidemann, “Socialization just as soon as it can be done without the smashing of the industrial system.”

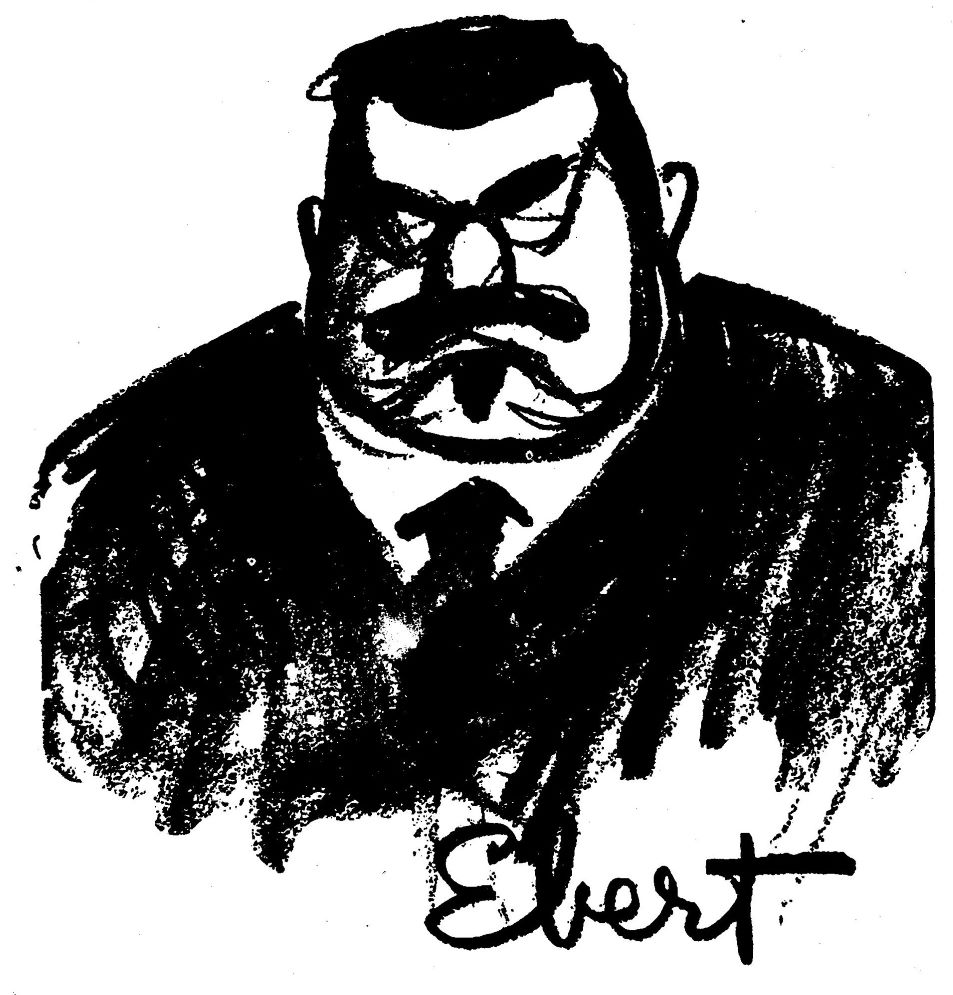

The fraud was too subtle for the minds of German labor. There was no sharp distinction between what Liebknecht said and what the bourgeoisie’s Socialists could say just as well. It boiled down to a question of which leaders to trust, and though all thoughtful proletarians were readier to trust Liebknecht than Scheidemann and Ebert, still very few are thoughtful, and even fewer of the war-tired men were willing to fight over the only issue that was clear to them—that of their leaders’ personal integrity.

***

Everybody has to be Christmassy when Christmas comes near, no matter who one is. The German newspapers just had to have something Christmassy to talk about, and so they took President Wilson. As this day approached, the inveterate desire to have a Savior bloomed into eulogies of the President across the sea. The fabian socialist paper, the “Republik,” filled its heart and its first page with “The Hope in Wilson.’ Wilson was the Messiah, he was the Star in the East, he was the Three Wise Men, and the camel, too.

The fabian fish swallows whatever is on the hook—all the fourteen hooks.

* * *

In a quiet suburb I rented a room with heating and bath included, only there was no fuel and the bath was not working. Amongst the abominations of hyper-decorated furniture, sea-shell bric-a-brac and oil paintings from the furniture store, I made my home. I rented of a funny little, wrinkled-faced, white-haired woman, four feet tall. She had a five-foot sister, equally, aged, who worked out in a tailor shop. Both were old, old maids.

We quickly got acquainted, and I soon learned that they were very respectable people; they had always been connected with the Herrschaft (gentility). They had served a Graf. Their family, their mother before them, had worked for the Graf and Grafin all their lives, and the Grafin had left them some money, said little Frau Four-foot, only the sly lawyers had cheated them out of it. They would be rich now, with thousands of marks, if it hadn’t been for. They had always been connected with the Herrschaft. And their mother would have been really married, on the Graf’s big estate, if it hadn’t been for–well, anyway, the Grafin promised to take care of them always. Always, all their lives. She had said it just that way many times, once right in the presence of the Graf, when they were little girls and the Grafin was a young lady.

In the evenings when I came in to rest from sputtering machine-guns, bloody sidewalks and the blazing light of the day, these two little ghosts of the past would falter into my room to show me the old, musty documents “with the seals right on them” to prove their connection with the Herrschaft of long ago.

To my perplexity I discovered that I was their “Herrschaft” now. They came into my room every morning to bring with great ceremony my ersatz coffee, to bow stiffly before me, to open the window curtains and to place at the bedside my carefully polished shoes which they had cleaned in the night. They had to have a Herrshaft.

On the wall hung a cheap engraving of God standing in Heaven, behind the spinning globe, His hand raised in benediction. A lady angel flew with art-school grace, at the side of the picture, and fat-legged cherubim floated in the scrolly clouds. God’s head was drawn too big for his body, and His beard was lopsided, but the composition was good and altogether it was a pleasing picture. Beneath, in Russian, German and Polish, was printed “God’s Creation.”

I told little Frau Four-foot that the picture was good. Her face lightened up. “Ah, we are Catholics, Herr.” And so I learned that the whole intellectual life of the two wizened wrecks was supplied by the priest around the corner, and their votes carefully directed to the Catholic Zentrum party.

The Volksmarine Division had come to Berlin in the conscious glory of having started the German Revolution.

I have several times noticed that it is the first task of a “revolutionary government” to get rid of the soldiers that made the revolution. It seems to be a natural phenomenon and has perfectly sound logic. Troops start revolutions by refusing to obey, by themselves deciding whom to fight, and when to fight and how; and after the overthrow they retain the habit. Now it is obvious that soldiers must obey the “revolutionary government.” Therefore the “revolutionary government” must get rid of the soldiers that made the revolution, and must hold power through soldiers that have been obeying all along. Scheidemann knows that.

The government decided to quietly slide the Volksmarine Division down the skids of demobilization. City Commandant Wels decreed that it was the irrevocable right of the tired revolutionary heroes to be demobilized and go home.

The Volksmarine Division suggested that as it had precipitated the revolution at a time when Scheidemann

was supporting the Kaiser, it would be best for them to remain under arms to safeguard the revolution. But Commandant Wels pronounced the Division demobilized and stopped its pay.

The division went all at once, with rifles on shoulders, to see the commandant about it, and took him back with them into the Schloss (Kaiser’s palace).

The First Cavalry division of Potsdam and some young troops just off the train from the murder expedition in Finland with that now staunch pro-Ally, General Mannerheim, surrounded the royal palace and stables. All night the artillery and machine-guns bombarded the atrocious architecture of the Schloss (thereby atoning in some measure for German destruction of good Gothic architecture in France).

When the cannon were heard throughout the city, the promenaders on Unter den Linden said “suppression of criminals” and went on promenading. Some Democrats mostly remained in their “referred-to-the-executive-committee” state of mind and kept to their daily tasks of conveying the best food to the bourgeoisie and protecting property.

From some factories on the outskirts of the city, several hundreds of workmen who didn’t have party discipline, left their labors upon which the life of the community depended, and came down town with revolvers—not in uniform and with no authority whatever. In front of the Lustgarten they waved their revolvers, shouting, “Nieder die Regierung; alle Macht dem Proletariat!” and clashed with some Social-Democratic Party soldiers who were fully authorized to preserve order. The shooting, yelling and general disorderliness drew crowds and caused a chaotic condition from the working-class district back of Alexander Platz, clear to the down-town streets. It created scandal. People said it was awful, and then explained how it happened. The promenaders stopped in little clusters to explain; some of the shabbier men began to argue, and then the crowd commenced to think.

It is the strangest sight in the world when a crowd begins to think. Promenaders stop promenading, and nondescripts quit hurrying to where they are bound, and nobody says, “Move on, there!” but everybody talks earnestly to someone he never saw before. France tried to explain it in describing the French Revolution, and since the Russian Revolution a few more efforts have been made to tell how crowds think. But most of it remains to be told, it is almost an unexplored field. It is an astonishing, flabbergasting thing. The first thing required is a lack of policemen, then a big, life-and-death issue, and there comes a sort of chemical action in the crowd, like the turning of milk. The human mass that was flowing easily in whatever direction its owners chose to pour it, suddenly congeals at a peal of thunder–cannon thunder–ceases to pour and is no longer sweet to the taste of those who have been drinking it. Something happens that we shall have to think about a lot and talk about until we figure out just what it is.

The crowds gaped about the scene of battle all night, watching the government’s batteries fire, and then walking over to watch the shells explode in the midst of the dead architecture and live sailors. They talked about how the fire spat from the guns, and how loud it was, and how soon the “disorder would be suppressed”–and then they discussed which side was right and talked about what the sailors had done; the bombarders talked, too, and pretty soon they suddenly wouldn’t bombard any more.

In the morning more people came down from their homes and stopped in the streets to argue, full of the virgin opinions of the day before. “Finden Sie in mir einen Verbrechen?” politely expostulated a neatly dressed Spartakist, and I knew that late arrivals had been saying that the marines were bombarded as criminals. No-o-o-o! of course the gentleman was not a criminal; and so the argument continued throughout the day. The soldiers. melted into the crowd, to some extent, leaving their officers in perplexed impotence. The mob, the complacent mob that governments use, wouldn’t pour any more.

I can never forget that Christmas Day on Unter den Linden. Discarded handbills of every political faction. lay in a trampled and sloppy carpet over the street. The human flood swirls and eddies and breaks into little groups that are polite, kindly-attentive to anything that anyone will say. The little groups get abstract and then concrete, and are amazingly wise. People that never thought before, begin to think right before your eyes. Men that never talked before suddenly speak wisdom that they never had before. It seems as though a whole multitude suddenly begins to revel in the delight of using some obscure muscle that it never used before. There are no policemen, and everybody forgets about law and order and is kind and courteous instead.

As far as the eye could see, knots of men and women were talking, talking, discussing the fourteen dead sailors in the Marstall (royal stables) and whether it was right that they should be dead. Nearly everybody started out with the official opinion that it was right to attack them; nearly everybody finished by thinking it was wrong to attack them. The ten thousand tiny voices made one big rumble; a multitude buzzing, milling, milling, churning about all day. A crowd thinking.

This happy Christmas evening I went calling on the marines in the Marstall. Their piratical-looking, cool-looking, kind-looking outposts stood a hundred yards. from the building, explaining to the crowd’s volunteer messengers, who, when they grasped a good argument, hastened away to use it to finish up some dispute on Unter den Linden. Inside the Marstall, the door guard, whose head was horribly bloody and bandaged, asked my companion for a cigarette and asked me to tell him something about Russia. Another asked me if I wanted a rifle and a window to shoot from. The sailors told us that they didn’t know very much but that they knew whoever holds guns, rules, and I thought that was a great deal to know.

When the soldiers began to think, the government decided not to disarm the sailors. It is astonishing and funny that governments can’t do anything when crowds and soldiers think. But they don’t think often.

* * *

On this birthday of Jesus who drove the money-changers out of the Temple, some ragamuffins with Jesus in them drove the “Scheidemaenner” out of the Vorwaerts printing shop. The unbeautiful, artificial-stone walls contained the Altar of their Kingdom to Come. They had seen their Temple defiled by hands that had been in glove with the Kaiser. Every day they saw the Vorwaerts–their Vorwaerts–turn crafty words to defeat their dreams, and that in the very time of dreams coming true. They couldn’t stand it any longer, and at last they took machine-guns of a kind that Jesus didn’t have, and they drove the money-changers out of their temple. The next morning, Vorwaerts spoke as they wanted it to speak, with a wild, lusty call to the revolution, the kind of call for which Vorwaerts was founded many years ago.

The ragamuffins were wheedled and driven out of the Vorwaerts office by promises that the Kaiserliche editors would write differently in future; but on the morning after, the restored editors printed heavy, respectable, flustered editorials taking back all the promises.

* * *

Fourteen dead bodies of workingmen or sailors are a dangerous thing for a government to leave lying around. There have to be funerals.

By tacit agreement the half-Jew Liebknecht was to be the priest at this funeral. Nobody thought of anything else.

The government retired to obscurity for the day, with as many officers as possible barricaded behind machine-guns. The bourgeois press frantically appealed to comrade workers to come to Socialist meetings in the outer residence districts; out of reach of the sight and sound of the terrible Liebknecht.

All of downtown Berlin was given over to the funeral, every street. First the mourners–the avengers?–met in Siegesallee, and Liebknecht stood before the coffins and told in simple, brutal brevity why the sailors had been killed. Then the monster cortege, like a black and red serpent, pushed its head through the center of Berlin. A taxicab squeezed through the jam in Unter den Linden and stopped in front of the Police Presidium. Liebknecht climbed onto the roof of the taxicab. He stood silently. Then he pointed to the closed, shame-faced door of the Police Presidium. Not a word. He was startlingly like another gaunt, kind-eyed Jew who first delivered to me the message of the Revolution, years ago, in America.

Liebknecht told again sharply and plainly why there were dead brothers to bury. His boney, prison-pallid finger pointed persistently at the Police Presidium, which we knew bristled with machine guns behind its shutters, at his back.

A crowd of workingmen lifted him down and into the car, seeming proud to touch him, and the taxicab. drove away with a sailor on its top, a big automatic pistol in his hand.

In front of the Schloss stood Ledebour on a stone wall, wearing a long black cape, his white hair bared to the rain. He, too, told why the government had fired upon the revolutionary sailors. There was a queer impression of rivalry between these two men.

Some of the bourgeois didn’t want to take off their hats as the funeral passed, but some workingmen spoke to them, and they did.

In the evening, little Frau Four-foot and her five-foot sister waited for me, trembling with fear. At their church they had learned that the Spartakists were going to kill everybody. To me, as the Herrschaft, the only authority besides the priest, they came to ask if they were likely to have their throats cut-whether the murderous orgy of Spartacus was likely to spread to their dingy neighborhood. “Herr Minor, are they going to murder us, two poor old respectable women? Ach, schrecklich! schrecklich! The Spartakists kill women and children, they despoil the church, they have no mercy. You say it is not so, Herr Minor? Ach, you do not understand. They will surely kill us, and will capture the Rathaus where the money is that we ought to get only the lawyers cheat us, and they will steal it. Ach, ach!”

I tried with all the authority of my status of Herrschaft to quiet them, but always a bomb or a cannonshot would detonate somewhere, and they would turn pale again and tiptoe off to bed to tremble and whisper all night, afraid to sleep.

* * *

I think it was the 30th of December that the “Kommunist Party” was formed, and Karl Radek made a speech urging a revolt and an entente with Russia. The German bourgeoisie was perplexed and terror-stricken. It was so damned irregular! The Germans had never gotten used to what the Russians call “illegalism,” just as Americans have not yet learned that method of revolution and will not learn about it until they shall have grabbed Russia through Kolchak, and try to rule it.

***

The New Year brings fresh preoccupations. The bourgeois and monarchist newspapers thunder at the proletariat to please, please come and vote. “Democracy!” they gladly, or anxiously, cry. They have been told the great secret that democratic government doesn’t hurt property. “What is the difference,” they delightedly they delightedly whispered to one another, “between a republic and a monarchy? Only this, that a republic is a safety-device monarchy! Ha, ha!”

* * *

Chief of Police Eichorn was caught in the most treasonable conduct! He had given arms to factory workmen. What a police chief! It was unheard of, irregular, undisciplined, un-party-disciplined.

And so, on Sunday morning, January 5th, Vorwaerts and the bourgeois papers announced firmly that Eichorn was dismissed.

But have you ever seen a government decree issued while factory workers had guns in their hands? It is as impotent as a solitary flake of snow in April. “Auf! Auf! Arbeiter!” called the Rote Fahne and Freiheit, and by nine o’clock in the morning the great Siegesallee swarmed with workingmen, couples of them, here and there, carrying machine-guns between them. By ten o’clock the streets were flooded with a human sea.

At Pariser Platz a wagonload of government handbills arrived. They were unloaded in the middle of the Platz, the stacks of paper carefully loosened up, piled so nicely as to tickle one’s sense of order, and set on fire. One of the stokers politely gave me two copies of the circular at my request.

The head of the procession swept past, composed of Spartakists, Independents and a tremendous mass whose only politics was a consciousness of being workingmen.

Twelve men with rifles stepped out of the procession, heavy cartridge-belts around their working clothes and factory grease on faces. There is something terrible in the sight of men in working clothes with rifles in their hands. They strung out, twelve abreast, and walked quickly up the broad avenue on the side that was not filled with paraders. A hunchbacked man came out of nowhere and silently began to tear anti-bolshevik posters off the walls. Spectators looked at him without speaking, and then joined him. He reminded me of a man I had seen selling newspapers under Brooklyn Bridge. The crowd stopped singing. Someone called out “Scheidemann!” and the voices roared, “Nieder, nieder, nieder!” in unison. “Liebknecht!” “Hoch, hoch, hoch!”

I ran ahead, hardly realizing what I was doing, to watch the twelve men with guns. They were walking rapidly. Each military officer they met they asked courteously–yes, damn it! with the most kindly courtesy–to take the cockade off of his cap. Each officer complied with sheepish readiness. Except when some unarmed workmen accosted officers in a side street, out of sight of the men with guns. An officer refused to remove his insignia, sneered at the shabby man before him. The shabby man slapped the officer’s cap off and the amazed gentleman drew back into the arms of his wife. A half-dozen angry bourgeois stepped between the opponents. “You shabby fool! You treat an officer of the German army this way!” A workman ran up with a big revolver, and the officer, wife and bourgeois melted into the crowd.

The street was being littered with falling, tinkling, rolling little painted tin disks that marked the sacredness of the Kaiser’s own officers. “And this Unter den Linden!” exclaimed a woman. I stepped across an open space in the crowd. Someone caught sight of my nondescript costume of fur cap, high boots and Russian army coat and shouted, “Der Russe!” Everybody smiled and someone called me “comrade.

Across the avenue came a big limousine with a shiny bright officer sitting stiffly in the rear. Workmen shouted, the chauffeur tried to outrun them, but some young fellows headed off the machine. The General was asked to get out and have his epaulettes taken off. He hesitated. They jerked him out of the car and hacked off his shoulder-straps with a big knife. Another high officer tried to cross the avenue in an automobile, and then several more. Soon a troop of happy small boys was kicking the shiny gold braid of the Kaiser’s glory up and down Unter den Linden. I stood entranced on the corner.

I went out to Alexander Platz, where Police Headquarters overlook that Poor Man’s Square. The tall red brick building was surrounded by immeasurable waves of shabby men, waves that surged and ebbed and flowed about the foundation of the building where workingmen had got rifles for their own cause. Waving hats and hands and smiles were the foam on these waters. It was the first time that I had ever seen a “police chief” loved out in the open by shabby men. But damn it! he was not a real police chief.

The government soldiers did not come anywhere near Alexander Platz that day, and there were no policemen in the police headquarters, except Eichorn who had been “removed.”

The revolution always won at those moments when it had a concrete issue.

* * *

On Monday, Liebknecht spoke in Siegesallee, urging the workmen not to allow the government to remove Eichorn. Liebknecht looked tired. I went down Wilhelm Strasse, where, near a government building I saw two hundred men from factories, with guns in their hands. They were just standing around. I asked some of them who they were. I expected them to say “Spartakists,” but they only said “Arbeiter,” and I was surprised to realize how dangerous it sounded.

Vorwaerts had been captured again! And here was the paper on the street, edited by the ragamuffin Jesuses. It said, “Up, Men, Up! All on the street! The Revolution is in danger!” I went down to Mohren Strasse, near the best-built church I ever saw its nooks and corners make good sanctuary against bullets. A government machine-gun on a nearby stone balcony sputtered away now and then, but it was shooting over our heads at something further off and its ways were soon learned by the crowd which stepped back and forth, gracefully avoiding its stream of bullets as well as the occasional passing taxicabs.

An automobile drove past us with a dazzling bunch of gold lace and uniform to the door of the Kaiserhof Hotel; no one could see who it was. “Ludendorf?” whispered the crowd. “Hindenburg,” said one. “The damned dog,” said another.

* * *

For one memorable day the German government was confined to about four city blocks at Wilhelm Platz. Elsewhere everybody seemed to be joyously thinking, forgetting about the government. The soldiers most of them said they were neutral. They were trying to think it out (and did not succeed in thinking it out until after they had been disarmed).

Wilhelm Platz was crowded with irate, with scared, with sick bourgeoisie. With them were some workingmen, timid, well-behaved, hesitant people who watched other persons with great concern to do properly. Ebert came to the side window of the Reichskanzlei to make a speech to the little cramped street that seemed all that was left of his domain. He appeared worried. Someone fired a rifle to call the crowd to attention. Ebert jumped. It was a mistake to fire the rifle; everybody was startled and failed to understand it. Ebert talked; he said what was in the papers that morning. I couldn’t help laughing. A government with all its clothes off is such a tiny thing.

Over in Mohren Strasse a few Spartakist partisans walked into the square to argue with the bourgeoisie and the tame workmen. The arguments became heated. The Spartakists were outnumbered. A big Spartakist sailor, empty handed, was arguing at the corner where the Kaiserhof Hotel abuts into Wilhelm Platz. The bourgeois closed in on him, pushed him; pulled him and shook fists in his face. Suddenly someone fired a pistol. The sailor lunged to make room for himself and then pulled from his shirt a hand-grenade. The crowd scattered as he tossed the bomb. Silhouetted in the white smoke I saw a bunch of black rags that went up and them flopped in the gutter, a dead man.

The crowd scattered to the corners of the square, and the bourgeois began beating up the propagandists. Too-thick crowds packed about each of them, pummeling them with such fists as can reach an individual in a too-thick crowd: A rusty-haired Spartakist tried to cover his face with his arms, lunging back and forth as fists and fingernails caught him on cheek and neck. A big man with a derby hat and cutaway coat hovered on the outskirts of the trampling group, trying to reach the Spartakist’s head with a piece of board. Nervous anxiety covered his face as his reach fell short several times. As he tried and tried again, I thought, “that’s a man who succeeds in business.” The crowd thinned out between him and his mark, and he brought his stick down on the bobbing head. A slab of hairy skin peeled off, and there was the white skull, which turned red. The man in the cutaway coat dropped his board, dusted his hands and walked away.

A little ragged Jew ducked like a rabbit through the legs of the assailing crowd, crawled on hands and knees and dashed away, knocking down two who tried to stop him. A pink-cheeked fat man broke a stick over the head of another. A well-dressed boy of sixteen began to cry and said to me, “It isn’t right, it isn’t right!” A big, old man with a sad face began to break up all the sticks he could find, saying, “It is better so.”

***

I found Herr X. sitting lazily in the lobby of the luxurious Adlon Hotel. When he saw me, he motioned a cordial invitation to a second big arm chair. Herr X. had a proclivity for American newspaper men, and no one had yet warned him against me.

We talked half an hour about the treaty then being drawn up in Paris, he sounding me for speculations as to its probable harshness. A rifle fired outside.

“What do you think of the Spartakists?” I asked. He smiled faint-heartedly. After a bit, he said, “You know, I can’t live any way except as a bourgeois…Maybe the Spartakists are right, but that is not a question for me. I am a bourgeois, and I must live and act as a bourgeois.”

“The Spartakists have captured the Anhalter Bahnhof,” I read from my afternoon newspaper. He frowned, and then he smiled like a good sport. “It looks as though we are going to lose, but we can do nothing but go on and try. As long as any soldiers remain loyal, we must keep them fighting. This is the only life I can lead this life here–” and his gesture indicated the luxury of the big hotel.

“You had better become a ‘people’s commissar,’ I taunted. “Take my advice; study up a socialist vocabulary.”

“I suppose,” he grinned, “the first thing they would appropriate would be this hotel.”

“Headquarters,” I replied. We heard a machine-gun spit, in the distance.

“I’m afraid I shouldn’t master the Socialist philosophy,” said Herr X.

“Socialist vocabulary,” said Mephistopheles, through me.

He smiled. “You know my friend Scheidemann?” “No,” said I.

“Scheidemann is a good man,” mused the Herr. “Socialist?” I asked.

“Well,” answered Herr X., “he’s-well, Scheidemann knows that these theories of the fellows out there on the street wouldn’t work.”

“Is Scheidemann, a Socialist?” asked I again. “Call him a non-Socialist, if you like,” replied the Herr. “He knows those theories won’t do at all–those I wouldn’t call him theories out there on the street…insincere–not at all.” Herr X. looked at me just a bit distrustingly.

***

“You couldn’t do without Scheidemann and Ebert,” I said softly.

Herr X.’s face lightened and he inclined toward me, a sympathetic hand upon my arm. “You appear to understand,” he said wonderingly. “You don’t seem to be like most newspaper men. They don’t think about such things.”

A little spasmodic firing in the distance. Noske’s men. “I wish you’d meet my friend Bernstorff.”

“I suppose,” I said, “you’d have been expropriated already if it were not for the Majority Socialist Party–“

“Do you see that?” he said. “The advantage we had is that the German working class was organized and accustomed to putting their faith in responsible men whom they could trust–“

“Whom they thought they could trust,” I interrupted, and he looked at me suspiciously again. “–and whom you could trust,” I added.

He smiled with relief. “Scheidemann and Ebert are splendid men. In the crisis, nobody could save the situation except men who were known as Socialists.” “And yet, who are not Socialists?” I asked.

“Oh, they are members of the Socialist Party; have been for years.”

“But they don’t want to put over Socialism,” said I. The time we are concerned “Not for the present. about is the present.”

“Tell me,” I said, “isn’t it true that what you need is a government that calls itself Socialist, but is not Socialist?”

“You’ve got it right,” laughed Herr X. with animation, “but I never heard it put that way before. Don’t you want to meet Bernstorff?”

***

Leipsiger Strasse is filled with workmen carrying rifles and hand-grenades. From the War Ministry a machine-gun opened fire into the thick crowd. The workmen scattered to the roofs and windows of houses, from which they rained bombs and fired rifles upon the War Ministry.

The government officers sent out a promise to quit firing. The fight stopped and most of the workmen wandered away, a few remaining to load the injured into an ambulance.

Then the government opened fire again. Five dead and fifteen wounded. January 7th: The “Boersen Courier” (Stock Exchange Courier) contains a stirring appeal–“TO ALL WORKERS’ AND SOLDIERS’ SOVIETS OF GERMANY!”–telling the working class just how the editors think it can emancipate itself from Capitalism. Of course, order is the first thing.

* * *

Workingmen have captured and made forts of most. of the newspaper offices.

Noske declared martial law, some people said, and some said he didn’t.

January 8th: The revolutionary workingmen met in Siegesallee, in the beautiful Thiergarten. At one end of the fine driveway stands the Iron Hindenburg and down both sides are statues of royal heroes of Germany’s past, in a style called typically German, but really conceived in that monument foundry to the bourgeoisie, the Ecole des Beaux Arts at Paris.

Across a stretch of park, through the winter-naked limbs of trees, could be seen the Reichstag building. And many eyes looked at it through the trees, from Siegesallee. It was held by government troops, and in the distance the tiny noses of machine-guns peeped through the stone balustrades. Workmen began to drift over toward the Reichstag building, and lean against the trees and look.

The workmen hailed the soldiers as “Brueder,” but there was no response. Some went out into the open and shouted, asking the soldiers to talk to a committee. No reply. They waited a while.

It was one of the most dare-devil things that ever happened: a hundred or two men with rifles and machine guns charged across the open square at the Reichstag building, machine-guns methodically shot them to death. It is impossible to know why they did it.

What soldiers are those on Brandenburger Tor? Spartakists? But nobody knew. Nobody ever knows who anybody is in a city revolution. I passed under the great arch. There was a tall, corseted looking officer, his neck held in a four-inch white collar. He leaned over a nervous little man who had a cartridge-belt wrapped around his waiters’ dress-shirt and a too-long rifle in his hands. The big officer talked as though ordering a meal, and the little waiter seemed worried to get the order right. “Government troops,” I knew.

Firing began from all sides, and I walked down Unter den Linden with an inarticulate notion that I wanted to be among the other people if I got shot. The noise stopped. The crowd milled about as it had in the earlier days when it was making up its mind. For a half an hour. At the corner of Wilhelm Strasse the crowd gathered, an open space of two blocks being kept clear between there and Brandenburger Tor. Workingmen were talking to soldiers. “Are you not our brothers? Would you shoot us? Come over to us. We all want Socialism.” A message came from Brandenburger Tor. “Don’t let the crowd talk to you,” was the order to the soldiers. The crowd stepped back and then commenced to talk again. “We only want peace, brothers. Why do you kill us for the Kaiser’s officers?” Another messenger arrived from Brandenburger Tor. This time he whispered his message. The soldiers withdrew, and the crowd stood wondering and talking.

“T-R-R-R-R-rat-tat-tat!” a big-calibred machine-gun spouted from Brandenburger Tor. A man in sailor’s breeches threw up his arms, a heavy bullet spattered through his neck. It spattered through, and sloshed blood around. He flopped onto the street and slid, scraping the skin off his cheek-bone on the pavement. His head was half torn off and purple stuff poured out, which I stepped in because I could not stop quick enough. A small boy smashed against the wall with a bullet through his leg, and rolled over on his back.

* * *

On January 9th and 10th the white heat of battle flamed on Jerusalemer Strasse and Linden Strasse, clustered with newspaper offices, very much like our own Park Row. The “Taeglicher Rundshau” fell to the government troops, then most of the other bourgeois offices. Vorwaerts, the last stronghold, held out.

In a lull in the fight, I slipped into the Vorwaerts building, past the big paper-roll barricades and the friendly-looking men who were looking out through the cracks at their sight of day.

L–was sitting at a desk, sleepily trying to work, and talking to another man about getting some food. L– told me how they felt about Vorwaerts, as I have written it in this story. The next day L–was killed.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue:https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/09/v2n09-w19-sep-1919-liberator-hr.pdf