Speeches from the sessions on ‘The Revolutionary Movement in the Colonies and Semi-Colonies’ by delegates of the Arab world to the Comintern’s Sixth World Congress held in the summer of 1928. Contributions from Haidar of the Palestine Communist Party speaking for the illegal Egyptian party as well as the Syrian-Lebanese Communist Party (which became its own member at this meeting, and rejecting mandatory boundaries would divide into Syrian and Lebanese parties), two Algerian delegates, Ben Said and Aberderrame, and Mustapha from Tunisia. All dealt with the problems of being under tutelage of the C.P.s of the colonial countries, many North African Communists first organized while living in Europe and struggle to implant in their native lands. Coming after the collapse of the ‘First United Front’ in China and the withdrawal from left and radical forces from the League Against Imperialism, the Congress faced a changed situation. As part of the larger ‘Third Period’ shift, the new theses made a dual priority of Communist Parties in colonial and semi-colonial countries leading struggles of ‘class against class’ and for ‘national liberation’, which contained some obvious contradictions, discussed at the Congress. Haidar is S. Averbukh, any help identifying the others would be appreciated.

‘Revolutionary Movements in the Colonies: Speeches of Arab Delegates at the Sixth World Congress’ from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 8 No. 72, 74, 76, & 78. October 17, 1928.

‘Revolutionary Movements in the Arabian East’ by Haidar (S. Averbukh, Palestine)

[‘Haidar’ was a name used by S. Averbukh who led the PCP from 1924-9. Originally from Ukraine, he emigrated to Palestine as a member of Poale Zion where he would reject Zionism and join the Communist movement.

Comrades, the Arab problem, the Arabian East, is absent in the theses as well as in the reports on the colonial question.

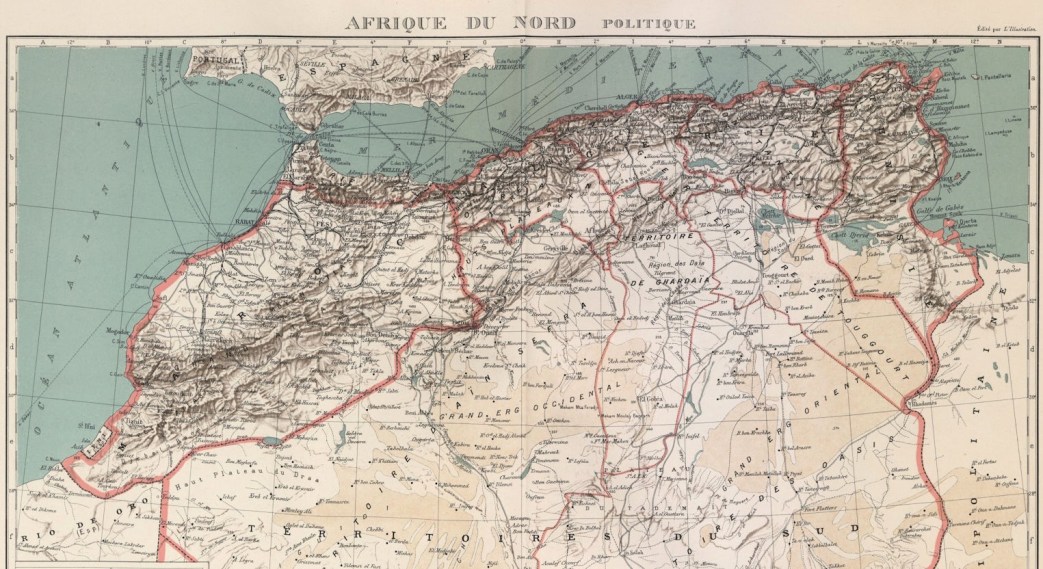

I believe that since the Indian problem has been put on the order of the day, it is high time to take up the Arabian question. This question is of tremendous importance, because we have here in a relatively small place a large number of important problems and questions concentrated, a number of different types of imperialist policy, and of varieties of colonial bondage. We see here everything from the shameful slavery of the Soudan to the refined form of slavery according to the latest feat of imperialist wisdom, the mandate system.

The force of the revolutionary movement has gone through the following stages. The first period from 1917 to 1922, During that period the imperialist powers are only beginning to frame their plans for the partition and occupation of these countries. During this period we saw an extraordinary growth of the revolutionary movement. The British had to increase their troops in the Iraq to 120,000 men; France had to maintain in Syria an army of 120,000 men, and many thousands of British soldiers were held in reserve in Palestine, Egypt and Soudan. In Egypt there was a strong type of revolution which embraced all the elements of the population “from the fellahin to the family of the khedive”, as it was put by a certain imperialist. In the country districts there were numerous risings and revolts and demonstrations, and the whole series of assassinations during a short period there were 260 successful terrorist acts carried out.

In the Iraq the guerilla warfare took the shape of regular battles in the course of which the British troops sustained over 8,000 casualties.

In Syria we witnessed a whole series of guerilla insurrections which were described as banditism in the official reports of the French general staff.

In Palestine there were Jewish progroms, as the British incited one nation against the other in order to sidetrack the nationalist movement.

In spite of its tremendous power, British imperialism was forced to make some compromises.

The Iraq mandate was annulled and substituted by a “voluntary” treaty; Egypt was declared an “independent country”, while Churchill annulled in the White Book the famous Balfour declaration concerning Palestine. Imperialism capitulated, and the so-called honeymoon of the native national bourgeoisie began. Encouraged by the political concessions obtained, the bourgeoisie gathered its forces, the national economy began to develop, and a rapid growth of capitalism was observed in the provinces, particularly in the domain of agriculture. The whole picture was changed: the old patriarchal feudal order on the land had collapsed, the communal ownership of the land (“Mushaha”) was given up and its place was taken by private ownership. Hand in hand with the development of private ownership in the land, there developed the capitalist forms of agriculture, the concentration of the soil, and the centralisation of the rural economy. A strong process of differentiation began among the fellahin in the villages: there appeared the kulak, a figure hitherto unknown in the village, and by his side the landless agricultural labourer. The old division of the village into “Homullah” (clans) gave place to the new division into classes. The place of the old feuds among the clans, blood vengeance etc., was taken by class antagonism and class conflicts. The countryside began to grow. The middle peasants began to dig up their hoards of gold coins and to purchase live stock, machinery and implements. The capacity of the home market grew, the local industries developed; in short, the capitalist development went on at an accelerated pace. The relations with the imperialists became strained again, and the centre of the nationalist movement was shifted from Central Arabia to the industrial and commercial districts, to Syria, Iraq and Palestine. At the same time a realignment of the forces went on. Instead of the old feudal and tribal divisions there came the new class divisions. As the class character of the society grew, its different manifestations became more and more pronounced. Not only was the bourgeoisie above the old feudal elements as regards culture, but it proved far more tractable and amenable to peaceful negotiations. It was in its ranks that the so-called national reformism emerged and developed.

During that period there was also manifested a second characteristic aspect of the revolutionary movement in these countries: there arose the labour movement. If we draw a comparison between the labour movement of these countries and that of China we are struck by the following facts: in China the working class became active as a class already at the outset of the revolutionary movement (the Northern expedition, the Shanghai revolt), was organised in the trade unions, and had a party which actively participated in the events. The opposite situation was to be observed in the Arabian East, where the workers took the field after a tremendous delay. The working masses as such constituted only the cannon fodder during the revolts in Egypt and Syria, whilst they were entirely absent as a class, as an organised force, The Egyptian Communist Party began its activity, not with forming a common Kuomintang, not by supporting Zaglul-Pasha, but rather by bitterly denouncing him.

All this happened six years ago, before the spread of the tidings of the Chinese revolution throughout the East, and so the mistakes of the Egyptian Party, particularly its isolation, led to grave consequences, to a complete detachment of the revolutionary movement from the common national movement. The result was that the Wafd Party, the adherents of Zaglul, had put themselves at the head of the Egyptian workers. They gained the leading role in the organisations and in the rural districts, whilst the Communist Party made its appearance when the tide was already receding. We had to win the working class when the revolutionary movement was already declining. When the organised working class began to push to the foreground, the bourgeoisie sought to come to terms with the imperialists. I declare quite categorically that this striving after peace with the imperialists on the one hand, and the sham revolutionary attitude on the other hand, constitutes the very substance of the policy of Zaglul and the Wafd Party. This should be explained not only by their fear of the struggle and of revolutionary actions, but rather by their fear of the rival Communist influence. It is a well known fact that the British Delegation with Lord Milner at its head was boycotted by the whole people and it was only by means of threats that Zaglul was induced to negotiate with Lord Milner. Milner asked the Wafd Party: “Do you want it here in Egypt the same way as in Soviet Russia? Do you wish to court the bolshevist peril? And indeed, as soon as Zaglul got into power he began to smash the Confederation of Labour, our section of the R.I.L.U., and generally to persecute the labour movement. But here the Wafd Party began to meet with new difficulties. It needed allies, but it could not work hand in hand with the workers, and besides, it had lost every influence among the workers. It would like very much to work together with the imperialists, but the latter have neither the wish nor the ability to gratify the minimum of their demands. The imperialists want the Wafd Party as an opposition group, as a lightning conductor against the feudal elements, but on the other hand, they want to keep the Wafd within certain bounds and to keep an eye on its revolutionary influence.

What should be our attitude towards the Wafd? Some comrades believe that the revolutionary role of the Wafd has already been played out; that it has now become a counter-revolutionary force; that it has associated itself with the counter-revolutionary forces, and that there can be no talk of an alliance with it. Nevertheless, comrades, I believe that by boycotting the Wafd we shall fall into the opposite extreme and commit a serious error. I might formulate our tasks in Egypt in the following manner: no formation of an alliance, no creation of common organisations, but a definite permanent contact with the Wafd, a contact upon the basis of concrete actions. The turning of the Wafd into a mass organisation, into a democratic organisation, would mean the creation of an apparatus against us, an apparatus which would strengthen even further the influence of national reformism.

You speak now about the formation of a workers and peasants’ party. This is a mere utopia, not because there is a danger that the C.P. would become transformed into a petty bourgeois party by allying itself with the peasantry, but simply because this is impossible. There is no such Communist Party, there are no such cadres as might undertake the task of organising the peasantry. The peasantry should be handled in quite a different way. I therefore urge the formation of peasant (fellah) committees, co-operative societies, different economic organisations, e.g. mutual aid, legal aid, etc., to which the agricultural labourers, the fellahin and the poor peasants should be attracted. We must bear in mind, comrades, that the Egyptian fellah works six months in the year as a wage earner, and the other six months as a landholder, so that it is rather difficult to draw the line between the labourer and the small peasant.

Vassilev (from the floor): “How will you join these elements in the co-operative movement?

They have common material interests. The fellah suffers from the speculators, and is dependent upon the usurers. There is a strong co-operative movement supported by the nationalists, and if we are looking for a basis for our activity, we must make use of it.

A few words about Arabia, Assyria, Palestine and Iraq. In Syria the national liberation movement suffered a great setback after the revolution, nevertheless the opposite thing has happened in that country from what took place in Egypt. It will perhaps be too strongly put, but I find no other words to express my thought. If the workers in China are resentful over the treason of the nationalists, e.g. Chang-Kai-shek, if we are all indignant over the alliance between the Chinese nationalists and imperialists, the opposite thing happened in Syria. At the moment of the revolutionary struggle, at the highest tide of the revolution, when the Syrian and Arabian nationalists fought with might and main, they were under the impression that they had been betrayed by the European proletariat. And this mistrust has not yet been dispelled. Now we are confronted with a big task: we must demonstrate that we are people of a different stamp from MacDonald who called himself a friend of the oppressed peoples, but who eventually acted in the same manner as the capitalists. Therefore the situation of the Communist Party in Palestine and Syria after the defeat of the Syrian revolution is a very difficult one. On the one hand, they have to unmask the traitors, the feudal elements, the representatives of the bourgeois democracy, and on the other hand they have to overcome the mistrust which has arisen among the native population against the European proletariat upon the aforesaid grounds.

Another problem, another danger which confronts us, is reformism. There has been a good deal spoken here about reformism, but I believe in no colony is it so strong as in Palestine. There we have a strong reformist organisation run by European imperialism and relying upon the Zionist movement, which has created for itself a strong basis. Although the labour movement is rather strong, nevertheless reformism is still stronger in Palestine. In the struggle against the communist influence it sticks at no means from the cruel persecution of revolutionary workers to the hoodwinking of the workers by the illusion that a “communist paradise” would be set up in Palestine. They are building a “communist society” under the protection of the British mandate.

The Arabian East is now at the parting of the ways. As the result of the latest events in Egypt, the question now confronts us no longer theoretically, but thoroughly in a practical shape. In view of the great events which are imminent in that country, we should not come too late. I maintain that if we stick to our present attitude, we shall positively be late.

I should like to conclude with the following remark. I believe that the greatest evil, or perhaps the greatest misfortune of the revolutionary movement in the East consists in the fact that it allows itself to be defeated singly in the different countries. When Egypt and Syria were quiet there was a strong movement in the Iraq. When the big miners’ struggle took place in England, it was quiet in our country. But when the revolutionary movement started in the East there was tranquility in England. It is the task of the European proletariat not to lag behind the colonial movement, as has been the case hitherto. This is our main task in the East and the indispensable postulate of victory for the national liberation movement.

‘Revolutionary Movements in the Colonies: Arabian East’ by Haidar (S. Averbukh, Palestine) Comrade

‘Revolutionary Movements in Algeria’ by Aberderrame (Algeria).

Comrades, in agreement with the Algerian Delegation I will endeavour to give a brief exposé of the colonial policy of French imperialism in Algeria.

First of all I will give you a few facts and figures to show you the results of colonisation. By expropriation by force of arms, by sequestrations, quartering of troops and annexations for various causes, 11 million hectars of fertile land have already been stolen by imperialism out of 21 million hectars of cultivated and uncultivated land; expropriation of land assumes every year a more accentuated form, it ruins the Algerians and drives them more and more towards the sterile south where they are decimated by periodical famines.

On the other hand over one half of the capital invested in North Africa is invested in Algeria. Owing to these investments the French imperialists exercise absolute control over banks, railways, mines, in a word, over the whole economic system. In regard to external trade, three-quarters is done with the mother country.

Algeria being a predominantly agricultural country, the French imperialists secure 80% of the agricultural produce. Moreover, Algeria is for them an outlet for their industrial produce to the extent of 90%. Suffice it to add that two-thirds of private capital are in their hands, as well as state power and finance, to give you a clear idea of the terrible grip French imperialism has on Algeria.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to assert that Algeria is a purely agricultural country; we witness there an ever-growing tendency towards industrial development.

Thus, in 1901 we had 1,000 industrial enterprises and in 1924, 22,000. Side by side with this an industrial proletariat is developing. From 60,000 industrial workers in 1921 the proletariat has increased to 180,000 in 1924. The production of iron increased from 74,000 tons in 1919 to 180,000 tons in 1925, and that of phosphates from 277,000 tons in 1919 to 815,000 tons in 1925.

Moreover, owing to lack of coal in Algeria the problem of electrification assumes an enormous importance for the development of industry. The distribution of electric power has increased from 28 million kilowatt hours in 1922 to 76 million in 1926.

This industrial development of Algeria is growing all the time and will continue to do so for various reasons:

1. The growth of agricultural production in the country is causing serious frictions with the producers in the mother country. To cope with these contradictions imperialism is compelled to create manufacturing industries to change the nature of the agricultural produce and facilitate thereby its sale.

2. Utilisation of the payments in kind owing to a better use of the ports (construction of railways, underground telephonic cables and improvement of the equipment of the mines).

3. Preparations for war and struggle against all the national revolutionary movements in North Africa for the domination of the Mediterranean basin.

To solve the problem of the self-defence of Algeria, imperialism has instituted “voluntary” recruitment of natives, a “voluntary” recruitment which owing to the economic and political pressure on the poor peasantry becomes compulsory recruitment.

In regard to repression, the following fact will give you an illustration of the regime of terror against the natives. For having dared to assert in public that a well known leader of the French Communist Party is an intelligent person one of our comrades was sentenced to two years’ deportation to the Sahara.

We have 480,000 workers out of six million inhabitants of whom 370,000 are natives and 110,000 Europeans, that is to say, 13% of the European population. The industrial proletariat numbers 180,000 including 108,000 natives. The important thing is that the native proletariat is the real industrial proletariat.

We witness in Algeria a rapid social differentiation and a certain radicalisation of big sections of natives. An utterly new and important fact is that a great desire for organisation is manifest among all the social sections of the native population.

85% of the population live on agricultural produce; in spite of the development of industry the rural character of Algeria has not changed. 55 to 65% are landless peasants (khames). These khames constitute 30% of the population, the rest are native land owners with either inadequate or barren plots of land. 30% of the European population live in the country; among them 33% are land owners and the rest are tenant farmers or agricultural labourers.

To illustrate what I have just said I will give you facts: in Saida poor peasants offered armed resistance to imperialism which caused the troops to intervene. In Bel-Abes we witnessed resistance to the occupation of the land. In Bougie agricultural labourers came out on strike without the help of any organisation. Among the urban proletariat there has been a series of strikes lately: gas workers’ strike in Algiers, a strike in the briquette factories Musel-Kabir, strikes among carpenters, tobacco workers, scavengers (Algiers). In almost all these strikes the natives behaved admirably and I am prepared to say that their attitude can serve as an example.

The attitude of the social democrats in Algeria is the same as in all the colonies. They support the imperialist policy against the natives, they are for assimilation and against independence and the abolition of the anti-native laws (Code de l’Indigenant). In their struggle against the Communists and the revolutionary trade unions the socialists have shown themselves as the most zealous servants of imperialism. I will give you a very characteristic fact which shows the social democrats in Algeria in their true colours. As a result of the struggle carried on by our Party against the socialists during the last elections they published in their organ the list of all the native members of our organisation whom they knew and declared that the real leader of our organisation is a native comrade, knowing full well that by denouncing the names of the native comrades to the police they would expose them to severe penalties. As a result of this the government took proceedings against our comrades.

Let us now consider the policy of our Communist Party in Algeria. Owing to the social composition of our Party in 1924 (small colonists, employees,) the Party pursued a wrong policy, a colonialist policy which impeded the development of the Party among the native masses who distrusted the Communist Party. Considering that our Party has not gone through the internal struggles of the French Party by which the latter was properly formed, we are four years behind the French Party.

In 1925, after the 5th congress, the colonial question was taken a little more seriously, but it was very much the same policy as in 1924.

Then came the Moroccan war. You know the attitude of the French Party. This attitude has very important consequences for our Party in Algeria which enabled us to take a series of measures. In 1926 the Party suffered from all the mistakes committed after the foundation.

In 1927 there were big internal struggles within the Party which led to the rectification of the Party in 1928. At present we have no more “colonists” in the Party, the natives participate in the Executive which has issued the slogan of Algerian independence.

It was for the first time that during the elections in Algeria our Party has carried out the policy laid down by the Communist International. The present executive is not yet what is should be; it suffers still from a certain political weakness but it is willing to work and has enough experience to put the Party on a sound new basis by getting rid of colonialist and vacillating elements and by supporting itself upon the natives for the struggle against imperialism. I want to say that these results could not have been achieved and such a rectification could not have taken place if it had not been for the close collaboration between the Algerian district and the C.P.F.

In conclusion, I will indicate what are the tasks of our Party:

1. It must become a real Communist Party of Algeria, by its composition and work.

2. It must win the peasants and agricultural labourers (I should like to say that nothing has been done in this sphere, but nevertheless we have attempted something in this direction since our last regional committee meeting).

3. For the improvement of the national composition of the trade unions with a stronger orientation towards the natives.

At a time when French imperialism is preparing to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the Conquest of Algeria, let us prepare to give our answer to the assassins and robbers of the colonial peoples and of ours in particular by mobilising the toilers of Algeria under the banner of struggle against French imperialism, for the independence of Algeria, as a stage towards the complete emancipation of the Algerian workers.

Comrades, to make it easier for us to carry out to a certain extent the tasks which the Sixth Congress will set us, we will have to raise the political level of the native active Party workers through the formation of upper and medium cadres capable of leading the revolutionary movement in the colonies under the banner of the Communist International.

‘Revolutionary Movements in Tunisia’ by Mustapha (Tunis):

In the Colonial theses, my country, Tunis, is mentioned in the second category, a country where the differentiation of classes is relatively little developed.

The countries of Northern Africa, where Tunis is situated, are primarily agricultural countries. Industry there is very slightly developed; it is reduced to the mining of iron and lead and principally phosphate. The few factories which exist in Tunis are connected with these mining industries. At the present time the proletariat employed in mining comprises 110,000 workers largely unskilled.

Almost the entire population of Tunis lives from or is dependent upon agriculture. In Tunis we have two million inhabitants, 1,500,000 of which live on an income of 100 to 210 francs. It is principally a country of the poor peasantry. For this reason, the question is of great importance, a fact which is not sufficiently emphasised in the theses. In Tunis we see different types of peasant economy. First of all there are the feudal peasants, who are numerically small, and the big landed proprietors. These feudal peasants exploit the great mass of Khammes, that is to say a kind of serf who cultivates the land of the big proprietors in a primitive manner. Then we have the middle and small peasantry owning their own land or else renting Habou or Wakf land. This Habou and Wakf property is inalienable property, very widespread in Tunis. Collective land cultivated by tribes also exists. These tribes have been driven out from the Northern region, but such collective economic units are still to be found in Southern Tunis. This great mass of tribes periodically suffers from drought and famine, and supplies the large army of nomads which regularly travels North to find work and greater resources.

Apart from this backward state of peasant economy, there are the large properties of capitalist cultivators and societies. These cultivators, bourgeois who have come from the ruling country, play a fairly large part. The contradictions between this foreign population and the majority of the native population aspiring to national liberation, give an agrarian character to the national revolution.

At the present time we can say that there is an intensification of the control of imperialism over the colonies, in Northern Africa particularly. It is what they call utilising the colonies. This utilisation takes the form first of all of the extension of colonisation. The new agricultural programme envisages the distribution of 300,000 hectares to the cultivators. A stronger pressure upon the natives must therefore be foreseen, as well as a more intense, more violent or more or less indirect exploitation, and a more complete alienation of Habou and Wakf property. But at the same time the big landholding bourgeoisie is to receive certain political and economic advantages, distribution of new lands, agricultural credits, etc…In this programme there is a plan for a new distribution of 20,000 hectares to some of the native families.

The utilisation of the colonies is manifested also by the extension of the mining industry, by the perfectioning of methods of exploitation, by the construction of new railways and roads, and by the building of new factories for the primary transformation of these mineral products as well as agricultural products. In this way the French capitalists are going to build factories in Tunis for the transformation of phosphate and also of lead, instead of exporting them in raw form as is done at the present time. New tariff conventions will enable French industry to find a greater outlet in Tunis. These new tariff conventions, which will have their effect on industrialisation of the country and on light artisan industry which is still well-developed in Tunis, are directed also against Italian competition.

A few words on the subject of the French-Italian conflict which is growing more and more acute. At the present time French imperialism is taking a great many measures for the defence of its colonies against the designs of Italian imperialism. First of all in the development of the naval base of Sidi Abdallah, the building of new railway-lines and strategic roads, especially in the direction of Tripoli. All this is being carried out in connection with the French plan of autonomous defence for Northern Africa, of which the Algerian comrade just spoke.

The Franco-Italian conflict has its effect also upon the internal policy of the French Government in Tunis. Through a clever policy of naturalisation, it is winning over part of the Italian population of Tunis, which constitutes a permanent danger for imperialism, because this population is numerically greater than the French population. Secondly, French imperialism is attempting to win over a part of the native bourgeoisie to its policy, because Italian imperialism is seeking to influence this native bourgeoisie. This Franco-Italian conflict threatens to give the national movement in Tunis an orientation in the direction of the defence of Tunis, i.e. in the sense of the defence of the Tunis “fatherland” which would actually result in strengthening French imperialism.

Our Party has reacted energetically, denouncing this policy of French imperialism in a manifesto. It has warned the population of Tunis against the manoeuvres of the two imperialisms and has issued the slogan of struggle against both these imperialisms and for the independence of Tunis.

I shall now pass on to the national movement itself. There is a national party, under the leadership of Destour, which demands the constitution. During the past years this party has gone through an evolution which is very characteristic. Formed immediately after the war in 1918, it carried on a certain revolutionary struggle in the course of the crisis of 1918-22, resulting in great mass action; many of its militants were beaten up. At one time there were more than 100,00 members, and its demonstrations forced the Bey of Tunis to submit the national demands to France. I must tell you that at that time the Destour party comprised nearly all strata of the Tunis population: feudal, petty-bourgeois and peasant. It was then that French imperialism began to practise its policy of corruption the first act of which was the concession to Tunis of the famous “reforms” of 1922, which conceded certain political rights to the feudal landowners and big landed proprietors and assured it the support of this class. The Destour party, after the events of 1922, slied into a policy of frank compromise and capitulation before French imperialism.

This policy of capitulation was evident at the time of the coming into power of the Left bloc, when Destour immediately attempted to calm down the effervescence which was evident in Tunis. It was shown by the alliance of Destour with the reformist-socialists, who are the worst lackeys of imperialism in Tunis. And when the workers’ movement reached its height in 1924 we found Destour renouncing this movement and attempting to break it up. Destour did nothing to support the militants among the ranks of his party who were persecuted by imperialism. He even abandoned some of these militants. This policy of capitulation was evident also during the Moroccan war, when Destour maintained a completely passive attitude.

This policy of capitulation and compromise was the cause of the almost complete liquidation of the Destour party which at the present time is kept alive only by a few remaining organisations.

Parallel with this treachery of the national party, the French Government practised an extremely clever policy of corruption. After having won over the feudal and landed proprietor class, it undertook to get a new strata of the population to break away from the Destour party, namely the middle section of landholders. I just told you that it distributed a large quantity of No. land among them. Although this measure was of no importance whatsoever, it sufficed to give the bourgeoisie a certain hope of seeing their lot improved by French imperialism. This policy of corruption was also one of the chief factors in the almost complete liquidation of the Destour party.

Recently the Government granted new reforms. These new reforms were received with satisfaction by the intellectual bourgeoisie which makes up the leadership of the Destour party, as certain political rights were given to them. The revolutionary manifesto of the Destour party in 1922 has been completely changed, although this programme contains nothing further than demands of the intellectual bourgeoisie.

While the leaders of the Destour party were carrying out this policy, we participated in vigorous struggles: resistance of the peasants to expropriation, unrest caused by the great famines in 1923 and 1927, demonstrations of the small traders and poor students, as well as the great wave of strikes of the Tunis proletariat during 1924 and 1925, which involved thousands of workers and were marked by the bloody strikes of Bizerte, of d’Harmann-elly, in factories and quarries and even in the mines. This great wave of strikes resulted in the formation of a national revolutionary autonomous trade union organisation of the Tunis proletariat, the Tunis C.G.T. But French imperialism at once launched a policy of ferocious repression against this great mass movement. In addition to the firing on strikers at Bizerte and the suppression of the strikes, it took the form of the arrest of many workers, the dissolution of the C.G.T. of Tunis and the Communist Party, the suppression of revolutionary publications and the banishment of the whole Central Committee of the revolutionary trade union organisation.

After this period of bitter repression there was a certain lapse in the labour movement. But with the increased exploitation of French imperialism, we are now facing a revival of labour struggles. At the present time the proletariat shows a strong desire for struggle and organisation. This organisation is being now carried on in the formation of reformist trade unions, within the C.G.T. trade unions of Jouhaux.

The Socialist Party of Tunis is composed of French, chiefly employees. Its policy is to serve French imperialism by upholding the illusions of the Tunis masses and also by the acute struggle against Communism and against the revolutionary national movement. The Socialist Party, which at the time of the big strikes carried on a huge campaign against the C.G.T. of Tunis, has a completely imperialistic policy which we can expose by careful systematic work. The organisation of the workers of Tunis which is now being carried on in the reformist C.G.T. is largely due to the loss of influence of the Communist Party.

I should like to say a few words about the Communist Party. Our Party was formed in 1920. In the beginning i had a great influence on the masses of Tunis. It even had a daily paper and a weekly. It was this Party which led the big struggles of 1925-25; and which was at the head of the C.G.T. of Tunis. Several of its militants were banished with the Central Committee of the revolutionary trade union organisations. But our Party could not hold out against the repressions. This was due chiefly to its poor social composition and to its poor organisation. But even though it was reduced to a very small group, the Communist Party was able to maintain its influence among the working masses. But it committed serious errors: for instance in 1925, the underestimation of the repression, as well as the failure to understand the desire for struggle and organisation among the working class; also its tendency to work as a sect, especially after the repression of 1925 and 1926 which tendency was favoured by the illegal existence it has been forced into; and then the underestimation of the government policy of corruption and of the Socialist policy of illusions.

At the present time these errors have been in part corrected thanks to the intervention of the French Party which has already devoted a great deal of attention to colonial work, which has not always been the case, particularly not in 1924 and 1925, when we were completely cut off from the French Party.

This new situation and these new conditions have forced us to adopt new tactics in order to put the Communist Party again at the head of the labour movement.

Our tasks now are:

1. The support of the revolutionary anti-imperialist movement and the exposure of its conciliatory elements.

2. The trade union organisation of the native workers, the necessity for regaining our former influence through an effective struggle in the very ranks of the working class, and by a serious effort to combat the reformist and Socialist policy.

3. The organisation of a strong Communist Party. The labour struggles and the present situation offer great possibilities for us to develop the Party, and we must therefore devote our efforts above all to a vast recruiting as well as to a strong ideological reinforcement of the Party.

I am convinced that through the new orientation of the Party, through serious efforts on the part of the French Party in the colonies and thanks also to the definite decisions contained in the colonial theses, we shall be able to form a strong Communist Party in Tunis, a Party which is truly Bolshevik in its social composition and ideological strength, and to gain again the influence which it had among the Tunis masses. (Applause.)

‘Revolutionary Movement in Algeria’ by Comrade Ben Said (Algeria).

To give a good idea of the question of the colonial workers in France, one must get at the root of it.

The problem of colonial workers in France has already received the attention of our Party.

This labour power played a very important role during the war. Recruited by force for starvation pay it was used for the manufacture of war material and for military work. Only an infinitesimal section was specialised and received equal wages with French workers. This encouraged clandestine embarkations which assumed enormous proportions. In 1920 imperialism, seeing that it could not put a stop to them, gave freedom of passage.

But the main factor which determined imperialism to make this concession was the lack of labour power in the colonies.

Before the war French capitalism suffered from lack of labour power. The war aggravated this deficit and brought confusion into the economy of the country. In the post-war period the problem of the reconstruction of the devastated regions, the trend towards industrialisation stimulated by the annexation of Alsace Lorraine, compelled French capitalism to introduce foreign and colonial labour power.

Colonial labour power (unskilled workers) and foreign labour power (skilled) workers, introduced in France after the war by French capitalism made the law of supply and demand function in its favour. From its exploitation it derived a great deal of prosperity; moreover it enabled it to constitute its industrial reserve army.

The revolutionary situation which arose after the war brought capitalism face to face with a series of problems, among others the introduction on a large scale of labour power from technically backward countries which are under its yoke. French capitalism imagined that this labour power would be in its hands a weapon which would crush all eventual movements of the working class for better conditions. It also hoped that the very low wages paid to the workers would create between it and the French workers continuous friction and antagonism and would be a means to reduce the wages of the latter.

Thus there were in France in 1924 about 300,000 North Africans including 70,000 in the Paris region. This number has been reduced to 100,000 including 40,000 in the Paris region. They are employed by various industries especially by the metallurgical industry. Their average pay is 20 francs. These workers returned and are still returning to France by various means clandestine embarkments, industrial or collective contracts.

The objective and subjective reasons which are at the root of this exodus are the pauperisation of the peasantry, the accentuation of the process of the proletarisation of the petty bourgeoisie and the artisans, the terrorist regime which has become the normal regime, the “high wages” earned by their compatriots who have already gone to France.

Collective recruitment through agencies has also played a certain role. Recruiters invaded the regions and dangled before the eyes of the natives enticing wages and wonderful conditions of labour. They frequently succeeded in making many recruits especially among the Khammes (landless peasants) who were atrociously duped in this manner. For when they arrived in France they found that their wages were 25 to 40% smaller than those paid to French workers; moreover travelling expenses were deducted from their wages although they had been told that they get a free passage. They are also made to pay for their lodgings (in insanitary barracks).

In 1926 a terrible tragedy took place in connection with clandestine embarkations. On a boat travelling from Algiers to Marseilles 25 natives were found dead in the ships hold, two years after the promulgation of the Chautemps decree which suppressed freedom of passage.

In spite of the suppression of the freedom of passage the number of colonial workers did not decrease till the economic crisis of 1926-27. They were the first to be dismissed. By roundabout methods used in certain regions they were compelled to go back to their country, whereas in the Lyons region they were repatriated by force.

Did our Party work among these workers? The answer must be in the affirmative although the work was not very adequate. Nevertheless the organisation of many recruiting and agitational campaigns, especially in the Paris region, can be reckoned among the real successes of the Party.

The organisation of Congresses of North African workers in Paris, Douai, and Marseilles were the culminating point of the great work in these regions. The Congresses, which were attended by many delegates from these regions, discussed political and trade union Theses and adopted two resolutions dealing with their immediate political and trade union demands. One must admit that it was a great error not to keep up the connection with these delegates which would have enabled us to group them in trade unions and to form among them regional cadres.

During the Riff war work among these workers was utterly neglected. Instead of taking advantage of the presence of these elements in France in order to explain to them the position of the Party and to help to develop their class consciousness which they were beginning to acquire under the influence of the economic conditions, they were utterly neglected. During the general strike declared by the Committee of Action against the war in Morocco these workers did not respond to this slogan as was expected of them. The blame for this rests with the regions and districts which did not do their duty in this sphere.

This defect was remedied to a certain extent by the creation of the post of colonial organiser which was very serviceable in the Paris region but had to be suppressed subsequently for certain reason.

Our comrades in the C.G.T.U. realised the importance of this question only much later. Till 1925 the Party alone carried on recruiting campaigns for the trade unions. At that date a part-time organiser was appointed but this did not have the desired results owing to the inertia of the Executive.

It was only in 1926 that the Colonial Bureau was reorganised and a permanent organiser was appointed.

We must admit that although at first this colonial bureau was fairly active and succeeded in grouping around itself energetic bona fide workers, this is no longer the case at present. The energy displayed at first has made room for complete inertia. For instance no preparatory work was done in this sphere for the last May Day. A few feeble efforts were made by the C.G.T.U. in regard to the colonial workers.

It should also be pointed out that even militant colonial workers are showing signs of inertia because they do not get the necessary encouragement and direction from the leading cadres of the Party. No work has been done at all among the Negroes and Indo-Chinese of whom there are 10,000 in France.

When the Party and the C.G.T.U. were embarking on energetic work among the colonial workers the C.G.T., through its Secretary Jouhaux, was demanding the complete repatriation of these workers on the plea “that these 300,000 colonial workers who have acquired certain professional skill can provide the technical cadres required for the further development of the French Colonies…

Soon after Jouhaux brought forward another very edifying proposal in the National Labour Sub-Commission to the following effect:

“Considering that the requirements of the natives are very modest and that their production is one quarter of that of the French worker, their wages must be established on this basis…”

This slogan issued by Jouhaux from the platform of the National Labour Commission where he collaborates with the big industrialists is taken over from an Algerian deputy. This representative of the colonies, who is himself a colonist and a mine-owner, formulated his proposals as follows:

“In Algeria shortage of labour power is the most serious problem confronting the colonisers. It is absolutely necessary that North African workers who are in France should not get such high wages. Taking into consideration this smaller productivity they must receive the same pay as workers in Algeria.”

Community of viewpoints between Jouhaux, the spokesman of the C.G.T., and the representative of the colonisers reveals the path traversed by the reformist organisation which has fallen into downright racial hostility and shows to these workers that it is the best supporter of the employers and colonisers.

It will be no news to you that the colonial workers will have nothing to do with it and that any attempt to form a reformist organisation is bound to fail ignominiously.

In this connection it should be pointed out that two police bureaux have been established in France, one in Paris for the Algerians and the other in Marseilles for the Indo-Chinese. These bureaux are above all to watch over revolutionary workers and to terrorise colonial workers who follow us.

By such means natives who are known to be active trade unionists or active Party members are dismissed from certain factories while others, in order to get employment, must produce a green card signed by this bureau to which employers apply for information about the workers they engage.

Our Party carried on an energetic campaign against the establishment of that detective institution which demonstrates the determination of French imperialism to apply to colonial workers the denizenship regime even in France. But this demonstrates also that imperialism is alarmed by the increasing sympathy of these masses for our Party.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n72-oct-17-1928-inprecor-op.pdf