To commemorate this week’s anniversary of January, 1919’s Spartacist Rising, the second-half of a forgotten minor classic–Robert Minor’s active first-person narrative where he observes–and lives–the chasm between the heroism and idealism of Spartacism with the brutality and ignorance of its executioners as grisly reaction followed defeat.

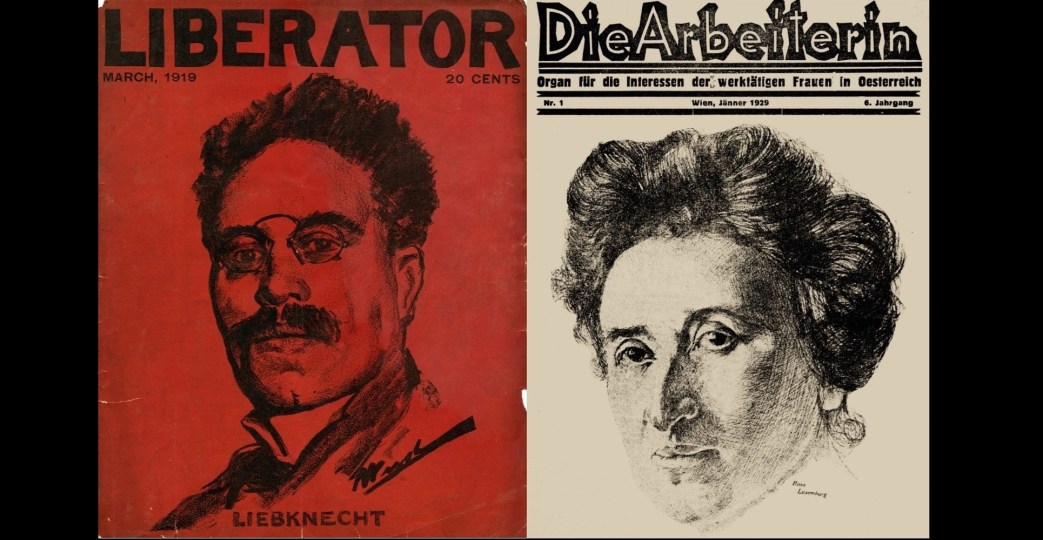

‘The Spartacide Insurrection: Part Two’ by Robert Minor from The Liberator. Vol. 2 No. 8. August, 1919.

Robert Minor was in Berlin during the Sparticide insurrection, and we believe his is the first sympathetic story of that event to reach America. Unfortunately he sent the story to us in two halves, and only one of them has arrived. It is the second half. It arrived about the time Minor was arrested by the British secret service on a charge which we understand was made by a provocateur who pretended to be distributing revolutionary literature in the American army. Many prominent people demanded justice for Robert Minor, and he has now been released. We shall probably get the other half of his story soon-with some interesting additions. THE EDITORS.

THE “Socialist government” had by this time largely succeeded in getting Berlin garrisoned by reactionary troops, with a heavy proportion of officers in enlisted men’s uniforms. The original conscript army of the Kaiser, the kind of an army that is dangerous, spent the time of the crisis in faltering, trying unsuccessfully to make up its mind. The Volksmarine Division couldn’t make up its mind. At the moment when the weight of one thousand well equipped troops would have turned the balance, captured Berlin and perhaps all Germany for the Revolution–the soldiers, the private soldiers, the soldiers that wanted a revolution, moped in the barracks, unable to decide what to do. The officers knew what they wanted, and acted quickly. I saw many a “private” doing sentry duty those days whose face had a singularly aristocratic appearance.

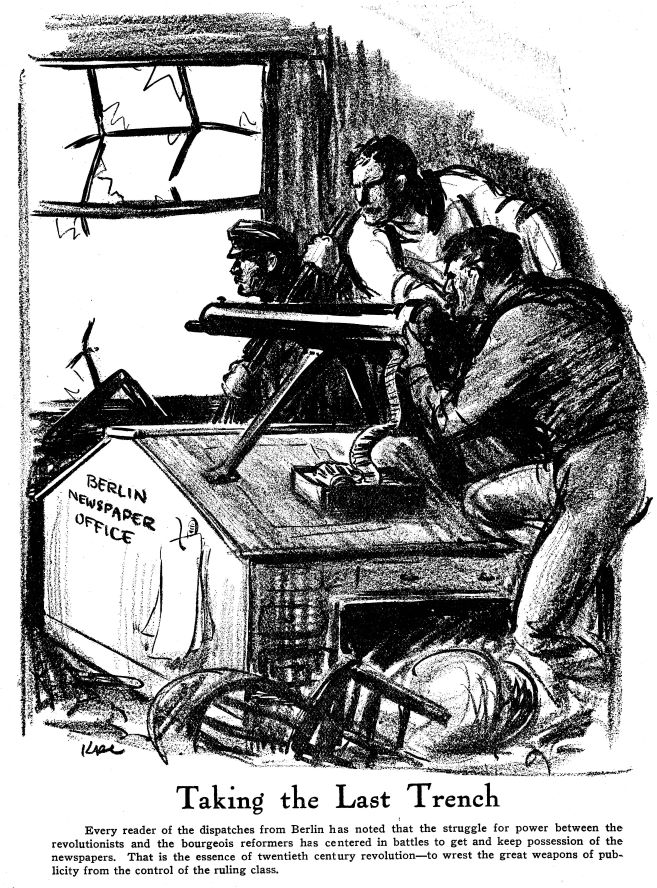

Thousands of officer-troops swarmed about the last remaining proletarian fort, the Vorwaerts building. Small artillery was brought up and began to pick away the front wall of the sacred printing house.

At last, a charge upon the shattered building, past the paper-roll barricades, over the dust-covered dead meat of the men that yesterday had told me about their “Temple.” And into the house, where the last dozen were captured. At the very end, a little black-haired Jewess arose with a sigh from her machine-gun and stood back against the wall to be shot. She was nineteen years old. All the prisoners (except the girl, they claim) were taken down into the courtyard and killed.

Frau Five-foot came to my door this evening. “Herr Minor, the rich people have white bread.” “Well?” “Well?” I asked. “Nothing, only they’ve got white bread. That’s all,” and she walked out.

Coal strikes in Westphalia. Grumbling in Berlin factories. Those who couldn’t make up their minds before began to make up their minds now, from the bottom up–from the belly up. After they had been mostly disarmed and the cities taken into the iron hand of their enemies, after their own friends of the vanguard had been killed.

After hope was gone, the Volksmarine Division made up its mind and began making a fort for itself in the working class district. Other soldiers joined them, and that strange hero, the empty-handed man in overalls, came out by many hundreds to patiently give up lives.

Again war flamed through Berlin. With all the machinery of modern armies, the working-class district back of Alexander Platz was reduced to broken brick and stone.

For four and a half years, patiently or impatiently, we had looked for the soul of Germany to express itself. Some of us–many of us–knew that there existed in the German man a spirit that would sooner or later somehow smash loose and free itself from the Hohenzollern-headed monster. Woodrow Wilson knew it and carefully couched his words to rouse in the German laborer a spirit of rebellion which he thought he could use for his own purposes. So obviously was the soul there that even the man called Northcliffe got a vague inkling of it and fumbled crudely with the kind of propaganda that he had heard would appeal to souls.

Perhaps we in America forgot that we, too, had something to express, while we fascinated ourselves in urging the German proletarian to express his soul before the firing squad.

We had all been looking for barricades in German streets.

I climbed over a barricade on Schloss Bruecke, near the Kaiser’s palace. Socialist barricade? Noske’s barricade. I was allowed to pass because I showed a card signed by “comrade” Noske proving that I was a bourgeois journalist.

On the proletarian side of the barricade all was shot to pieces by artillery. Blown up houses. Tangled trolley wires around a dead horse. A wrecked auto truck. A smashed subway station reeking with shell-fumes. A turned-over field gun. Two wounded men sitting on it. Two nurses. A man fixing a cafe window.

I went on past Alexander Platz, on deeper into the shabby rows of houses. I squeezed through several barricades. A crowd was in line showing passes to go through to their homes or business in the suspected and surrounded part of the city. Most of those who of the city. Most of those who had passes were well dressed, and the women held their skirts to keep them from snagging on a strand of barbed wire that stuck out into the passageway like an unruly strand of hair that won’t stay brushed.

On the other side was a man here and there, or a woman without a hat, looking hopelessly at the opening in the barricade. Some of the men’s clothes were freshly torn and streaked with white plaster-dust from cannonaded walls. Those mostly kept back around the corner. Their faces were strong, but pale. Their hands were conspicuous because they were empty. Some of them were boys, and these came out openly and looked at the guarded gap in the barricade. Barricade? Perhaps it was rather a pen. The barricades had come, in Berlin, and they were pens. The soldiers occasionally eyed the penned-in people and then turned to more immediate business.

On Frankfurter Allee, a sort of “Second Avenue,” A the crowds were hurrying along, keeping clear. man broke past a soldier and walked quickly on. The soldier shouted and cocked his rifle. The people scattered. The man was brought back and arrested. A little red-faced soldier, whose lower lip hung down and was too wet, shouted at the crowd and rushed toward it firing his rifle and then quickly reloading. The street was being cleared for a search of the houses. This was the heart of the workingmen’s district. I showed my papers to the red-faced boy-soldier. “Ach, so! Amerikanische Journalist. Bitteschoen.” I brushed quickly by; I thought he wanted to shake hands with me. Here the avenue was vacant on one side, except for a few soldiers, all nervously active. All of their mouths twitched and their lower lips were too wet.

There was a courtyard. An officer before it, pistol in hand. He turned around twice and walked in and out. Three or four soldiers, with rifles, stuck their heads out of the courtyard and then drew back. The officer frowned at me; with peculiar certainty I knew that he was wondering how he looked to me. He shut his eyes an instant and then stared at me again. I was startled; the man’s eyes were begging for something. It was all over in a second. He shouted, the He shouted, the crowd left. “Pang! Pang! Pang! Pang! Pang!” Five shots. The officer had been tensely looking into the courtyard; now his face relaxed. Six soldiers came out, their rifles emitting the slight smoke that smokeless powder gives. “There were five members in that family,” said a badly dressed fat woman at my side, and she quickly walked away.

Slow, regular shots were muffled inside the rooms of two apartments upstairs. I counted the members of the families.

“CRASH!” A bomb landed in the street. The soldiers scattered. Above the coping showed the tousled head and the shoulders of a man, who ran across the roof. roof. “Crack, crack, crack, crack!” the soldiers fired. “They missed him, Goddam it!” I shouted; or else I only thought it, I don’t know which. But at least I laughed, aloud, for a soldier turned his gun toward me–

“CRASH! BANG! BOOM!” Three bombs fell in quick succession from a window. Nearly all the soldiers vanished from the street and began to appear on the roofs. An officer with a pistol ran across the housetop. He was soft-faced and high-collared like the “Prussian officer” we used to see in caricatures. There were no more shots.

The desert-dreary look of a town that’s been shot up! I am always reminded of a dry waste of Arizona when I see a city where guns have been at work to make a millennium come (though, by God! I believe in guns) or to make us safe for democracy. It’s all there–the heartless dust, the tedium and thirstiness—everything except the cactus. But wait there is the cactus, too, in the shape of the tangled, nasty barbed wire, dusty and heartless, just like the weed with its sticky barbs.

Past a broken-down armored truck came four soldiers leading one man and two women. The two women wore plainest calico and no hats, their forearms red and bare as though they had just washed dishes–regular working-class house-fraus. The man was broad-cheeked and big-jointed; he wore a cap and no collar.

The penned-in people lined the street, their faces vacant of hope and their hands empty. The soldiers eyed them suspiciously.

The three pairs of prisoners’ eyes also searched the crowd. These eyes were seeking for somebody to say good-by to. The man’s deep eyes looked into me. A woman near me began to cry. Some one else did, too. They disappeared behind the barricade.

The cafes of Unter den Linden were crowded with bourgeois, comfortably sipping coffee. I met a young fellow-countryman who was in the service of the American government in Berlin. He joined me after bidding good-by to a Reinhardt Regiment officer. “That’s Captain W–I happened to overhear a conversation and so was able to give him information on which he arrested fifty Spartakist plotters. He’s a fine fellow.”

The special correspondents were sitting about the Adlon Hotel lobby, telling each other that “the government has the situation well in hand.” Correspondents are like clothespins on a line; straddled high in false prominence, mock importance, all performing the same function, all their little heads turned in the same lathe, so that if there’s a mistake in one, there’s the same mistake in all. What’s the use of remembering the different names of all the little clothespins that are just alike?

“LIEBKNECHT KILLED! ROSA LUXEMBERG DEAD!” shrieked the newspapers. How? “Liebknecht shot by guards while running away; Luxemberg woman torn to pieces by a mob infuriated by her crimes. Officers do their best to protect the woman instigator of violence, but are overpowered by enraged citizens.” The newspapers made it all clear; Liebknecht had, it is true, given an appearance of courage in the past, but at the last, facing the prospect of justice for his part in the criminal uprising against the Socialist government, he had developed a hysterical cowardice and had run away in fright, and the guards had been forced to the regrettable duty of shooting him, as the rules provide. The soldiers had done no more than their duty. The Luxemberg affair was a more distressing one, of course, but the officers had not realized how incensed the populace had become over the bloodshed caused by her. It was altogether a deplorable thing, such as should not be permitted to happen again.

The Majority Socialist and, bourgeois papers handled the affair as the American bourgeois press handled the affair of Frank Little and that of Tom Mooney.

The worst thing to me was not that Liebknecht and Luxemberg were dead, but that I had to quit believing in the German people. The mob–just a crowd of average Germans found by chance on the street–had dragged a sick old woman out of a cab, torn her body to pieces with their hands and thrown her flesh into a canal. Not soldiers–not brutality organized by authority–but plain Germans on the street, the German papers said. In a vivid flash was recalled to me the distorted face of an orator whom I had heard, three years ago, shout that the Germans were not human beings, but beasts to be killed, man, woman and child. It was impossible that that hate-mad orator was right, but my head swam with agony, in moral chaos; all faiths and loves went out of me.

In passing the hotel of K–a morbid fascination drew me in to visit him. He had often said “they ought to kill Liebknecht.” K–was huddled in a chair, his face pallid and drawn. He said he couldn’t write anything, this had shattered his nerve…After sitting half an hour, he arose and wrote a cablegram to his paper, “There is a peculiar irony of justice in the killing of this woman by the mob that she had sought to inflame.

Knots of gentlemen and ladies stood on the street corners, talking in relaxed, cheerful voices. A small boy caught the spirit of it and ran, shouting, “Old Liebknecht is killed now, and they threw the Luxemberg hussy into the canal!”

I hurried home and dropped, face down, on the couch…A knock on the door. Little wrinkled Frau Five-foot came in. Her bent figure straightened, her eyes glistened. “Herr Minor, have you heard it?—LIEBKNECHT IS DEAD!” The tiny sister appeared in the gloom behind, her face and white hair glowing as with a halo. “He is dead,” repeated the former; “they have killed him, dead. He can’t cut any women’s and children’s throats anymore…We are safe…What do you think, Herr Minor?” “Go away,” I said. “I’m sick.”

A half hour later they came back and peeped in the door. “Do you think we will be safe now, Herr Minor?”

Triumphantly the German bourgeoisie commenced its preparations for the Constituent Assembly, anxious to turn social attention into the sluice of politics.

A flaring red poster–of the “Socialist government”–announced ten thousand marks reward for the capture of Karl Radek. Someone earned the reward; there are men who do such things.

It hurts to think of Radek in prison. He is like what I imagine Debs was when he was young.

Slowly the truth was drawn out of the government’s lies. Liebknecht and Luxemberg had not been killed by the mob–not by the mob that I had been thinking on Unter den Linden. No, it was a deliberate murder by a government machine. I could get my bearings again.

“Before the war we used to make Pfankuchen,” said “Pfankuchen little Frau Five-foot to me one day. cooked with fat. Potatoes are good with fat,” she mused, tinkering with the carpet. “We could have Bratkartoffeln with the fat of pork…They cut off all the fat from the beef we get from the city. The rich people have bacon in their houses.” I thought of the dinner I had eaten that day in the Bristol Hotel, the great, luxurious “Home of the Counter-Revolution,” it is called–a dinner of huge, fat mutton chops, the incidental trimmings of which consisted of long strips of bacon.

A week later the sister came in from her workshop, late in the evening. “Herr Minor, the rich people have sugar in their houses, we have learned. Maybe they have other things to eat that we don’t ever have. They are big in the stomach, like there were lots of gentlemen before the war. Who can tell what they have in their houses? I guess it’s the Jews…But the rich gentiles look fat.”

Another week passed and she asked me what the Spartakists cut throats for. “Do the Spartakists want to go into houses to find out what’s in there?” Her voice became low and hesitant, bits of color flitting over her face. Half of a shamed smile. She left hurriedly, as though she had been dallying with a lewd fancy.

A month later the two old women came into my room in such a way as to make me lose my sense of Herrschaft. They forgot to bow. “Herr Minor,” began the bigger one, “there’s going to be something happening. We, eh–the working people” (she had never called herself “working people” before). The smaller sister pushed ahead and said: “The rich people have things in their houses, bacon, and white flour and butter, even. They make cakes, and eat them.” “We don’t get things like they do, and we work and work and work and don’t eat like they do.” “Yes, and they have bacon,” said the other.

“What is it all about?” I asked.

“There’s going to be a general strike,” said one, “and the working people are going to tear things up terribly, yes, schrecklich, and won’t go back to work until everything is pulled out of the rich houses–the Jews’ houses–and all the rich houses–and then they can’t have anything unless they work like we do, and we work too hard, and we won’t work too hard and we are going to have a revolution.”

The smaller sister looked frightened and pulled the other’s dress. The two quietly shuffled out of the room.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/08/v2n08-w18-aug-1919-liberator-hr.pdf