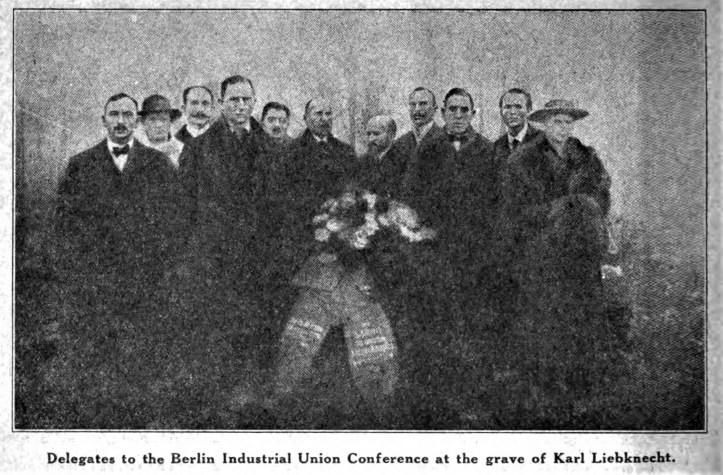

Participants in the December, 1920 syndicalist conference held in Berlin journey to the grave of he martyred Liebknecht on a blustery Christmas Day, less than a year after his murder.

‘The I.W.W. at the Grave of Karl Liebknecht’ by Theodor Plievier from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 1 No. 2. March, 1921.

DAMP westerly wind swept over the lowlands of North-Germany. Heavy clouds and drizzling rain moved over the earth and changed the face of the landscape. Snowy fields were transformed into gray and muddy plains, and the brilliant white snow that covered the streets and squares of the City of Berlin was turned into thick turbid waters.

Melancholy indeed was this Christmas day, celebrated in honor of the Messiah, who two thousand years ago walked the earth and called upon the poor and oppressed to fight against the powers of darkness. Clouds, dull and oppressive, hung like a funeral pall over the roofs of houses and drooped to the very pavements of the streets. The town presented a chaotic appearance: fog, rain and gusts of wind chased each other up and down its broad avenues; here and there one could occasionally catch fleeting glimpses of that colossal agglomeration of stores and churches, tenements and palaces, factories and workshops, known as the City of Berlin, in which millions of slaves of German capitalism live, work, fight and die.

Such was the appearance of Christmas day of the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and twenty, and sad were the thoughts of a small crowd of men—not quite a dozen—who had left a suburban railway station and were walking down a deserted street. After passing the last house on the outskirts of the town they came to a huge arch—the entrance to the Cemetery of Lichtenberg.

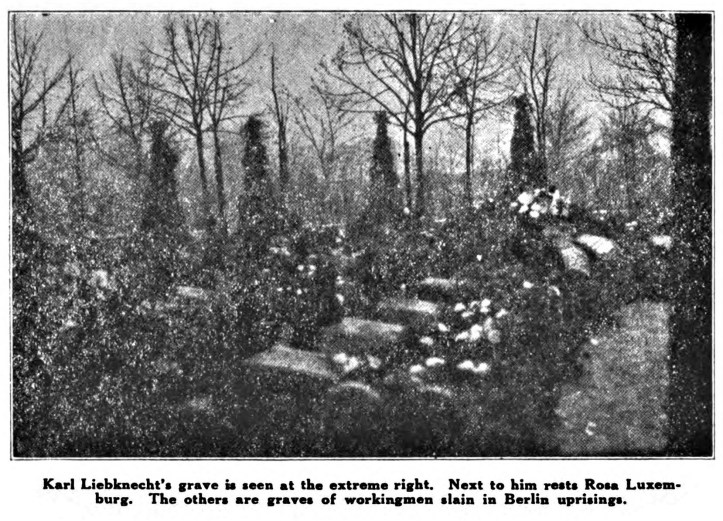

This grave-yard has an interesting history. Some fifty years ago it was founded by the municipality of Berlin as a buryingplace for the poor and the outcast, for those unfortunates who died in the streets, in charitable institutions, hospitals and prisons, for those derelicts, men and women, who had not the price of an “honest grave.” But, with the passing of years, it has gradually been transformed into the final resting-place of the bold and courageous men and women of Germany, of its pioneers in art and science, of its lovers of liberty, of its rebels against oppression in whatever form. Many a writer, many a scientist of world-wide fame lies buried here in this perfumed garden of roses. As one passed along its avenues and winding paths, lined on both sides with an infinite variety of flowers and shrubbery, one became aware that the Cemetery of Lichtenberg was, besides, one of the most beautiful in all Germany.

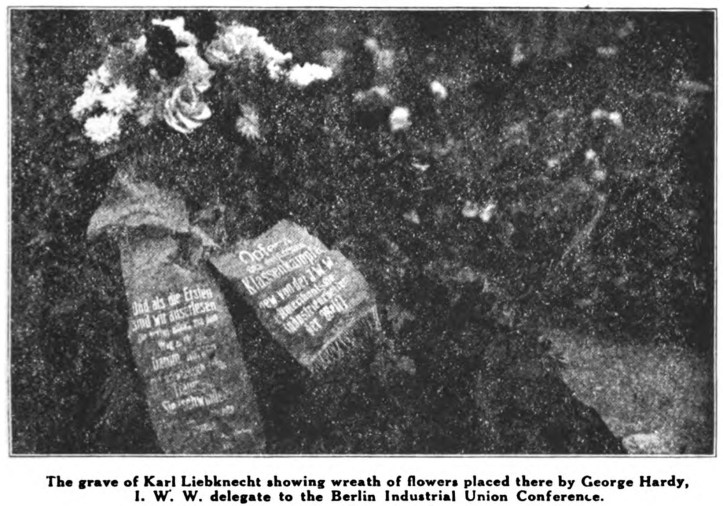

The group of men, carrying a big wreath of white and red roses, with a broad ribbon of the deepest red suspended from it, passed bare-headed a field of about two hundred mounds—graves of the victims of barricade-fights in the streets of Berlin. The very names even of some of these martyrs of the class struggle will forever remain unknown to posterity. All of them fought and died for a great cause—the liberation of the workers. Since November, 1918, the victims of the class-war in Germany number about seven thousand. This pile of dead bodies, this sum of wasted lives is the heavier a charge against the existing government at it calls itself a Socialistic one, and is elected and supported by the workers themselves. It is an everlasting “memento-mori,” a call of seven times thousand brutally murdered souls to carry on the revolution until its bitter end, until the establishment of the economical power of the proletariat.

The men walked on until they came to a spot where thirty-eight brave hearts had found their last resting place after a life of struggle. Here one of that group of pilgrims, George Hardy, the representative of the Industrial Workers of the World, reverently laid the wreath upon one of the mounds. The plain granite block at the head of that grave revealed the name of “Karl Liebknecht.”

The Industrial Workers of the World had sent its representative across the ocean to join hands with the European fellow workers, to pay homage to the martyrs of the German Revolution, and to bring greetings of courage and solidarity to the struggling Proletariat of Europe from the revolutionary labor movement of America.

This little group of men, assembled around Karl Liebknecht’s grave, represented the class-conscious workers of many lands. Their presence on the consecrated ground where lay buried one of the most valiant fighters for the liberation of the working class, whose life was like a blazing star lighting up the path of progress, symbolized the historic mission of the workers of the world—the abolition of wage slavery, exploitation, and the private ownership of the means of life, and the establishment of Labor’s Commonwealth.

To the Workers the Earth and all the Fruits thereof!

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrial-pioneer/Industrial%20Pioneer%20(March%201921).pdf