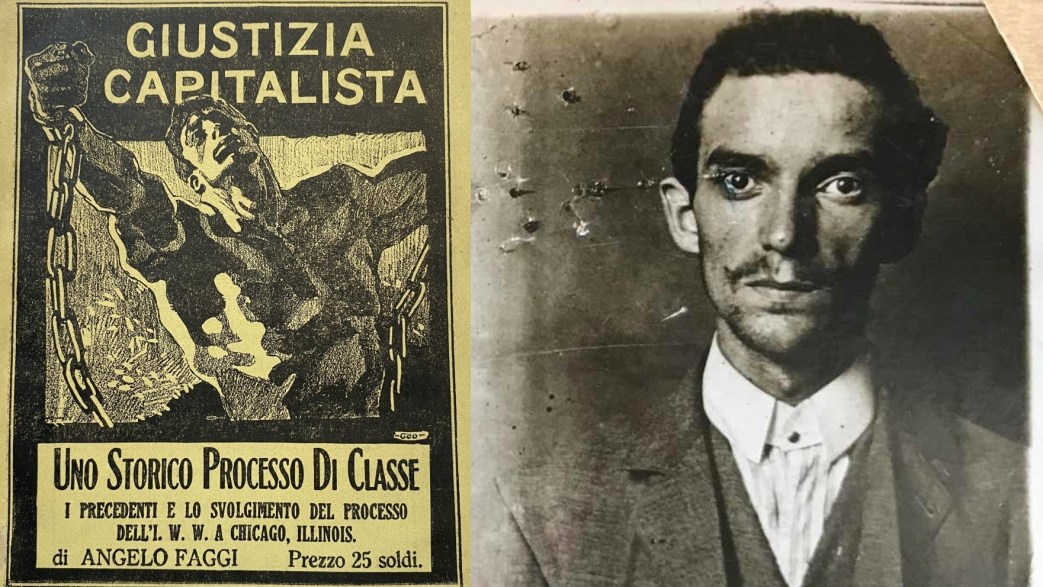

Essential history of the Italian working class by one who helped make it. Taking the story up to 1919, this also serves as an excellent background to the Biennio Rosso. Born in Florence in 1885, Angelo Faggi had an eventful life. Joining the workers’ movement at 15, he was first forced to leave Italy for his opposition to the Tripoli war, then became active in revolutionary labor circles in Switzerland and France. Central to the European campaign in defense of Ettor and Giovannitti, Faggi emigrated to the U.S. in 1915 where he became editor of Il Proletario. A major figure of the Italian-speaking I.W.W., like so many others he was deported in 1919, shortly after this was published. Back in Italy he was active in the Unione Sindacale Italiana. Elected to Parliament in 1921 for the Partito Socialista Italiano while serving time jail, and again fled to France after organizing the Arditi del Popolo to fight the fascists in the streets. He remained in France until Mussolini’s fall, dying in Italy in 1957.

‘Historical Sketches of the Revolutionary Labor Movement in Italy’ by Angelo Faggi from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 1 No. 5. July, 1919.

The labor movement in Italy has assumed a real class-conscious character within the past twenty years.

The year 1898 is written in the history of Italian Labor’s martyrology in letters of blood. The colonial war for the conquest of African Eritrea had brought the Italian people to such a point of misery, that on May 1, 1898, there took place in all the large cities of Italy, spontaneous demonstrations which became known as the “moti della fame,” or hunger revolts.

The revolutionary movement was then sparsely developed, either economically or politically. There were then only a few economic organizations in existence in the most industrially developed centers, such as Genoa, Milan, Turin, etc., and in the agricultural region of Emilia. The Socialist Party had very few members. Having only recently separated itself from the anarchist element (Genoa Congress, 1892), its activity was purely electoral.

Such state of affairs found its explanation not only in the industrially undeveloped condition of the nation as a whole, but also in the limited political liberties conceded by the monarchy.

In fact, the right of organization was contested and very much opposed; and depended in most cases upon the will or arbitrary acts of a minister of the government or of a prefect.

The hunger uprising of 1898, therefore, was really due to the serious economic hardships which the people were suffering; revolutionary propaganda played but a very minor part.

However, the government placed the blame entirely upon the anarchists, socialists, republicans, and even the democratic elements. The “hunger revolt” was stifled in blood. Hundreds of workers were slaughtered in the streets as they voiced their cry of, “We want bread and work.” At Milan, General Bava Beccaris even caused artillery to be brought into action against the protesting masses. On that same day thousands of arrests were made in all the cities of Italy; the “military tribunals” passed the most astounding and outrageous sentences upon hundreds of men who were entirely innocent.

Enormous Growth of the Movement

But it was from those same tragic days of May, 1898, that the labor movement was born and grew to gigantic size in its double expression, economic and political. The blood of the martyrs was on this occasion, as on many others, the fecund seed of the new ideal.

At the beginning, this movement born of tragedy and suffering rather than from the class-consciousness of the proletariat, naturally could not be an autonomous, independent movement of the working class.

The proletariat was but an infant in development at this stage, and could not proceed independently, supported by its proper conscience and guided by its own program. Like all youngsters, it needed a guardian. And the Socialist Party assumed from that day this task of guardianship, of political exponent of the workers’ interests.

The Socialist Party thus acquired great popularity. And while before 1898 it had sent to parliament only 5 or 6 deputies, in the first elections following the hunger uprisings, the number of deputies was increased to about twenty. Many among those elected to the office of deputy were in jail, and were then liberated.

The elections which succeeded the tragic days of May, 1898, not only sent a score of socialist deputies to parliament, but also sent another score or thereabouts among republicans and democrats; these were then considered as revolutionists, as they more or less expressed the popular opposition of that time against the dominant powers of reaction.

The government, presided over by the old reactionary Pelloux, presented to the parliament certain so-called “exception laws” to further restrict every form of freedom, especially the freedom of organization and the right to strike. The fifty deputies comprising the so-called “block of the extreme left” thereupon organized a desperate opposition, which culminated in obstructionism. Each one of them would speak at great length, some for whole days at a time, in order to play for time and to prevent the matter coming to any definite conclusion. This singular political fight was crowned with success, as the government, seeing it could not get its proposed laws passed, decided to dissolve the assembly and hold new elections, in the illusion of being able to get favorable action on its drastic laws with the new parliament.

But already the spirit of freedom had made headway among the people, and they elected to the assembly with even greater numbers the deputies of the democratic-Socialist opposition.

It was then that the government of Pelloux resigned, and with it were wrecked forever the proposed laws intended to throttle the most elemental liberties.

A Great Labor Victory

In 1900 the workers took advantage of the new breathing spell of freedom to everywhere form their own organizations. With the rise of the organizations there ripened a whole crop of strikes, practically all of which were victorious because they took the masters by surprise and unprepared, and the novelty of it at the time stunned them.

One of these strikes was particularly important, because it gave origin to another unfortunate reactionary attempt against the organizations. Among others, certain workers of the port of Genoa went on strike. And then, the minister Saracco, head of the government succeeding Pelloux, an old reactionary who could not adapt himself to seeing the workers enjoy certain few liberties, issued a decree dissolving the Camera del Lavoro, or local Labor Assembly of Genoa.

Once more there arose the necessity of defending the freedom of organization. But this time the proletariat itself took care of its own affairs. To the order to dissolve the Camera del Lavoro of Genoa, the workers of that city responded with the proclamation of a general strike. All the industries were paralyzed, and this paralysis threatened to extend to other cities, also, upon which the said industries were dependent for supplies for the port of Genoa. After a few unforgettable days of resistance, the Saracco government was forced to give in, resigning from office at the same time.

This was the first, real class victory of the Italian proletariat.

But another sensational event took place the same year. I allude to the killing of King Humbert I, at Monza, July 29, 1900, by the hand of the anarchist Gaetano Bresci.

Corrupting Politics

This event and the others already briefly referred to, had a powerful influence upon the succeeding directive agencies in Italian politics.

In fact, within a short space of time the directing classes took a new course toward so-called “liberal politics.”

The first government expressive of this new policy, intent upon circumventing and weakening with blandishments and promises the young but promising revolutionary movement which it had been impossible to destroy with open violence, was the one formed by the ministers Giolitti and Zanardelli about 1902.

The policy of these gentlemen was at bottom that of all governments which, inspired by a criterion of political opportunism, attempt to elevate the prestige of their institutions and thus attract the proletariat, with the enunciation of a program upon which participation in the government by the opposition element might be obtained. In this way they endeavored to first attract, and then bind, compromise and corrupt a part of the revolutionary movement. And such were the results. The promises of the two new dukes of the Italian monarchy were: freedom of organization and of strike, legislative reforms as concerning the women workers and child labor, etc. And the trap worked successfully.

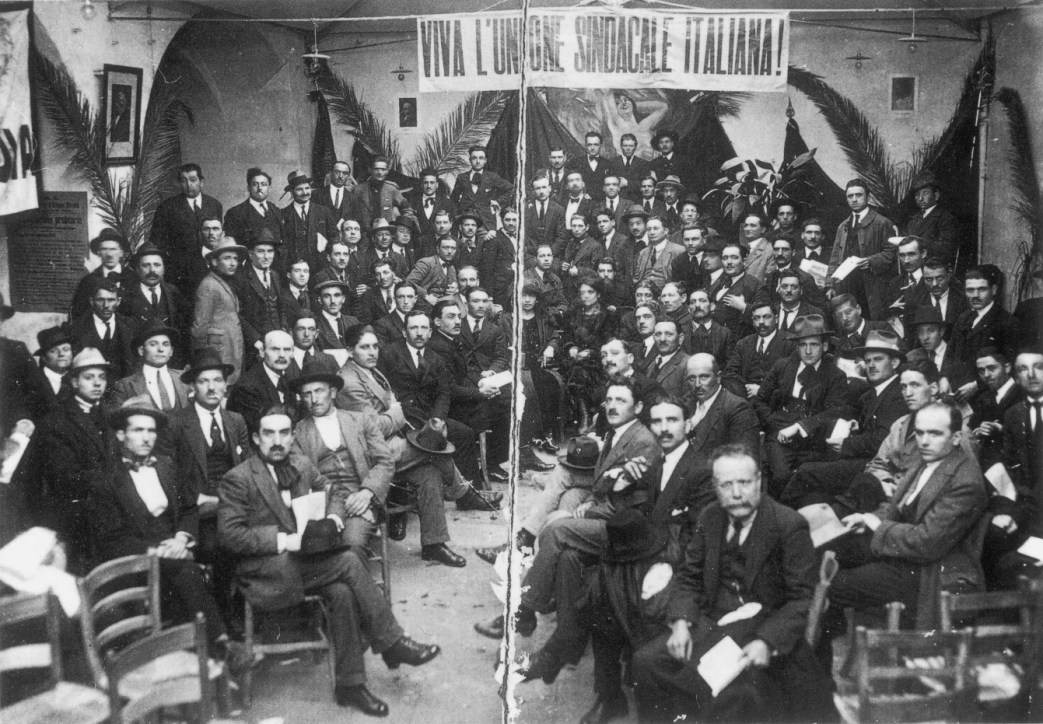

Bologna, 15–17 December 1912.

The democratic deputies gave their unconditional support to the new government; and soon afterward they actually entered in active participation in the government with their men. And the “liberal’’ government in turn supported the republicans and the socialists.

The Socialist Party had already become strong in numbers; had had for several years a daily newspaper (L’Avanti) and numerous weeklies in nearly all the principal centers of the nation. The workers organizations also had become powerful and numerous. They had already carried on some splendid struggles, with all the ardor of youth. Not even a shadow of dissention had appeared to disturb the feverish work of the organizers and propagandists, with the exception of some serene debates and discussion with the anarchist elements, then quite numerous. On the other hand they were engaged in defending the most elementary freedom, as an essential condition for the affirmation of any renovating or regenerating movement. Therefore unity arose naturally and spontaneously from this immediate and most urgent need of common defense.

The “Liberal” Government Massacres the Workers

But the new “liberal politics” soon threw the whole movement deeply into decay, discord and schism.

The attitude of the socialist deputies in giving their vote and their support to the “liberal” government, was the signal of internal struggle and factional fights.

In a short time there appeared clearly outlined, three different tendencies within the movement: the reformist, for supporting the government which promised political benefits; the center or integralist, which believed itself capable of giving its favorable vote, from time to time, to some good law, but never to support the general governmental policies; and lastly, the revolutionary tendency, which soon became the syndicalist faction of the party—and which insisted that in order to continue in conformity and accord with the labor and revolutionary character of the party, it was necessary to maintain a continued and systematic attitude of opposition to all bourgeois government.

In the meantime, while on one side polemics raged furiously, on the other side the labor organizations were forging ahead on experimental and practical lines as far as they could rely upon the promises of the “liberal” government.

The capitalists, recovered from the stupor of their first defeats, again set out for conquest and domination. They organized themselves in turn in formidable corporations to oppose the workers’ movement first, and to destroy it later on.

The struggle between capital and labor was thus rendered more arduous and bitterly cruel. Already the labor movement appeared clearly in its decisive class character. Revolutionary thought rose above the progressive level; it passed from the Socialist Party to labor organizations, which in the contacts of the difficult daily struggles were becoming more and more saturated with anti-capitalistic spirit; while the party, in its political contact and daily parliamentary compromises, was becoming more and more denatured.

However, the revolutionary element of the party did not abandon it; but, remaining in the party, engaged in a terrific fight in its campaign of opposition, of striving for control, of criticism and of revolutionary education, quick to profit from every event whereby it could demonstrate the inefficacy and fallacy of the reformist methods, and the danger of losing their identity as workers in the bourgeois elements to which these methods exposed them.

And tragically demonstrative events were not lacking. In some agricultural strikes, the authorities, forgetting the promises of the government, returned to the old repressive measures, even to ordering the troops to fire on the workers in demonstrations. The revolutionary element rebelled more and more against the deputies, who still continued to support a government which had several times stained itself with the blood of the workers. This argument fully hit the fusionist reformists and was unanswerable, but this element did not allow itself to be moved thereby. The adherents of fusionist-reformism were already tightly held within the meshes of bourgeois parliamentarism.

For a mere law or for any stupid reform, they were disposed to sacrifice everything. As to the massacres of the workers, Filippo Turati, leader of the reformists, in order to justify the murderous government and endeavoring to show that it could not be held to blame for the machine gun fire directed against the breast of the proletariat, is quoted as using a phrase, which became famous, to this effect: “It is not a case of violence willed by the government, but of occasional violence, inseparable from every labor struggle; it is merely a matter of some stray shot which has involuntarily hit some laborer…”

Thus, reformism justified even the massacre of the workers and continued undaunted, upon its course of compromises and alliances with the government, while not a week passed without some “stray shot” put to an end the cries of hunger or of protest of some of the proletariat.

Advance of the Revolutionists

And thus, the gulf of dissension in the party grew ever wider, since the revolutionsists emphasized more and more their fight against this reformist degeneration. Already the revolutionists had acquired strength and power; they had many weekly journals, such as “La Propaganda” of Naples, “L’Avanguardia” of Milan, etc. At Milan they had taken control of the local Socialist Party, forcing Turati to yield. Moreover, there was strong sympathy for them in many labor unions. And in a congress of the party held in 1903-04 the majority disavowed reformist methods and assigned the direction of the party paper and of all the directive agencies of the party to the revolutionists of the center,—that is, not the extremist revolutionists, who had almost become syndicalists, but a fourth faction owing its origin to the tactical differences or polemics of the preceding years, and which occupied a position between integralism, already mentioned above, and the extreme revolutionist ideas. This faction was led by Enrico Ferri, then a man of great authority, into whose hands passed the control of “Avanti,” the party’s daily paper. Ferri soon showed himself to be weak and ambitious, and a man of superficial and unstable convictions, so that in the course of six or seven years he was completely discredited as a party man.

The Biggest General Strike

At this period important events followed swiftly. The extremists approved of Ferri’s leadership of the party, though they continued intrepidly in their propaganda and their implacable criticism. To the papers they already possessed there was added a review, “Il Divenire Sociale,” issued twice a month and edited by Enrico Leone, a man of superior ability and culture, who always remained firm in his syndicalist convictions, through the stress of a thousand storms of various nature, and who even to this day indefatigably consecrates his generous spirit and his high intellect to the Idea which he embraced in his youth, or over 25 years ago. The review, “Il Divenire Sociale,” was a veritable temple of instruction and a bond of faith.

While the extremists were thus laboring so intensely, there occurred an imposing and memorable event: the general strike of September, 1904. This has certainly been one of the greatest affirmations of the Italian proletariat.

Another massacre of workers in a town of southern Italy had put the proletariat in mourning and had aroused deep indignation and the highest fervor. During this extraordinary psychological period, another grave conflict took place, not far away from industrial centers as before, but in Turin. There were dead and wounded. And then there followed more serious discussions of a general strike than heretofore. The revolutionists, at the recurrence of each fresh outrage or massacre, repeated: “It is necessary to respond to the violence of the enemy with the general strike.” But scarcely anyone believed in the possibility of carrying out a general strike in all Italy. Yet events proved otherwise. Soon after the slaughter at Turin, big mass meetings were held everywhere, and everywhere the idea of the general strike met with approval. In one of these meetings at Sestri Ponente, an industrial town near Genoa, the police intervened with brutality. A terrible conflict ensued. The police fired upon the assembly, and once more women and men fell on the public thoroughfares, pierced by the leaden bullets of the royal regime.

It proved to be the last drop that caused the cup of patience to overflow. Already partial strikes had been declared here and there following the bloody episode at Turin of two days previous. On the morrow of the fatal affair at Sestri Ponente, all the workers of Italy arose, as one man, spontaneously, irresistibly.

And the general strike was an accomplished fact. All the workshops, from the smallest to the largest, were paralyzed in an instant; all the trains were stopped; not a vessel left the ports. Even postal and telegraphic activity was interrupted, and bourgeois society, in all its manifestations and aspects, seemed shaking in its death shudders.

A few cities, like Genoa and Milan, were for two days completely in the hands of the workers. The barracks overflowed with troops, but the government kept them confined there. It did not dare, in those days, to throw the soldiers against the strikers who filled the streets or appeared everywhere in compact, solid ranks, expressing their scorn, in various forms, and showing a spirit of deep revolt; in front of the public or government buildings which were silent and closed up tight, and before the palaces behind the massive doors of which the terrorized bourgeoisie had securely shut itself in.

As if to show the incapacity of the politicians to express the proletarian psychology, it may be remembered that only a few weeks prior to this great and complete general strike, there had assembled at Amsterdam, the International Socialist Congress, where some forty odd intellectuals, representing the socialist parties of the various countries, voted a resolution decisively opposing the general strike.

Betrayals by Politicians

And how did this big general strike terminate? After three days of fighting, there began to appear here and there, on the part of the deputies and followers, urgings and invitations to end the strike. The Socialist parliamentary group, assembled at Milan and comprising the few who were able to attend, decided to issue an appeal for the cessation of the strike. The revolutionists opposed the move, but a considerable number of workers, in obedience to the call of the reformists, began to leave the heretofore solid ranks of the strikers, so that on the fourth day there was such a lack of unity and solidarity that the strike had to be called off. The police, again dominating the situation, wrecked their vengeance upon the workers who still remained true, and upon the last to give up the now unequal and hopeless contest. Arrests by the hundreds were made on the streets and everywhere, and the bourgeoisie, recovered from the fright, took to insulting and attacking the enchained and manacled workers upon the public highway.

What could the revolutionists gain by continuing the fight? Some few dared to urge the overthrow of the monarchy and the proclamation of a republic. But, generally, the thought of such a plan carried fear, it seems. Suffice it to say that the Republican Party, the most interested in the republic, and quite strong in numbers and prestige at that time, opposed the strike because of political jealousy. Still, the revolutionists wished to continue the tie-up, as they did not desire to fulfill the duties of “social firemen’ by putting out the sacred fires of revolt and breaking the impetus of the workers onslaught. Also they desired to continue because, aside from every other consideration, and interpreting the general strike rather as a spontaneous protest of the proletariat because of the massacres perpetrated by the government, they declared that, “the greater the intensity, duration and importance of the protest, the greater will be its efficacy, and the more effectively will it sound the desired note of reprimand and of warning.”

The reformists, on the other hand, were dominated, as usual, by electoral preoccupations! They well understood that the general strike, that tremendous explosion of proletarian wrath, tended to alienate, insofar as they the reformists and politicians were concerned, the sympathies of the workers, the small shop keepers, the petit bourgeoisie, and the middle class generally, the social groups which held the most considerable number of votes from the reformist socialist viewpoint.

For this reason they not only combated the general strike during its development, but they devoted themselves to heaping calumny and defamation upon it and its propagators for months afterwards; charging the revolutionists with being fools, lunatics and criminals, and the workers with being accomplices in crime.

The Idea of the “Workers’ Dictatorship”

The revolutionists not only defended the general strike and extolled its virtues and social necessity, but in doing so gained the inspiration for a new orientation of the revolutionary workers.

Prior to this great proletarian event, those of our comrades who were revolutionists were essentially political revolutionists. Only a relatively limited importance had been given the real labor movement as a factor of social transformation and reconstruction.

The life and conduct of the Party had been such that it brought these same revolutionists to confer an exaggerated importance upon the political and at the same time to neglect the economic factor.

But the general strike above referred to opened the eyes of the sincere revolutionists. From this great episode, frankly proletarian, they learned that revolutionary force under the capitalist regime emanated solely from the economic organizations of the workers; that only these possess the magic virtue with which to shake all of bourgeois society to its foundation; that bourgeois society rests upon the foundation of the factory, the shop, the mine; upon industrial production, in brief, and not on politics.

And since then, evoking the days when the workers, folding their arms, had automatically become the masters of the largest cities, they proclaimed that the future revolution could not be the result of political competition or rivalries, nor of legislative reforms, but rather the result of the class dictatorship of the proletariat become powerful and conscious of its destiny, through industrial organization. And from that time there was propagated a new phrase, and a notable one, expressive of the new interpretation of the coming social development: True Socialism is entirely and solely within the labor organizations.

The First “Syndicalist” Strikes

Soon there appeared in our press the new word: Syndicalism, which had already come to Italy through the French labor movement.

All the revolutionists applied themselves with diligence and care to impress a syndicalist character upon the workers’ organizations. They said:

“We workers, once organized, suffice in ourselves. We have no need either of deputies, nor of protective laws, nor of the paternalism of the state. We are Labor; Labor is everything; therefore we are the future. Let us organize ourselves in our unions, independent of any political group or party. By means of our solidarity, of our sacrifices, of our efforts as a class—we will create and mould our historic destiny.”

This was the new Syndicalist gospel that was preached to the masses of Labor.

In 1906 there occurred some great strikes among the agricultural workers of the province of Piacenza and a part of the province of Ferrara. These workers had embraced the syndicalist idea and their organizers were syndicalists. These strikers were completely victorious, in spite of the obstacles interposed by the reformist politicians.

Especially memorable was the second of these strikes, that is to say the one of Argenta (Ferrara) in which were involved also thousands of women, who gave splendid proof of heroic resistance during three long months. One incident of this strike to be long remembered and full of emotion, was the following: The association of the masters had hired hundreds of scabs at distant points. The arrival of these wretches by a special train was announced. Hundreds of women and men went to meet this train and came upon it standing at a station some distance from the city of Argenta. It was necessary to stop its progress here, because if it were allowed to reach Argenta, the troops would have rendered vain any attempts to get to it, or to resist the strike-breakers. The men strikers of the group boarded the train to persuade the wretched traitors to their cause to turn back. But these latter seemed fully determined to carry through their infamous undertaking. Squads of police arrived, and a tremendous fight followed.

The strikers were overcome. Already the train, protected by the police, was ready to proceed; the strike-breakers were about to resume their journey to Argenta. But the heroism of the women strikers, and their defiance of danger and death, had yet to be reckoned with. All together, they laid themselves prone across the railroad track, in front of the train. Had the train moved under these conditions, the results would have been most horrifying to say the least. The police resorted to every possible violent means to clear the track, but in vain. The women strikers would not budge from their strategic position. In the face of this spectacle, the trainmen declared they would not proceed. The scabs, perhaps a bit moved by emotion, but certainly somewhat upset if not indeed terrified, declared that they had been brought hence through deceit and fraud, and asked that they be returned to whence they came. And such, finally, was the decision arrived at by the authorities, to “evade grave disorders,” so they said. And so the trainload of slaves was turned back, defeated by that singular human barrier.

It was also during the strike at Argenta, in fact, that there was inaugurated for the first time the “exodus of the children,” or the taking away of the children of the strikers to be cared for at places far from the struggle, so as to facilitate the resistance of their parents in the strike and at the same time prevent the suffering of the innocent children.

These children were intrusted to the loyal care of fellow workers in other cities. This great sacrifice was also made by the parents among the strikers at Lawrence, Massachusetts, and proved to be a successful experiment, in that great strike in 1912.

In 1907, the Syndicalists, assembled in regular congress at Ferrara, officially decided to abandon the Socialist Party, severing all connection with it, and to devote their efforts entirely to the organization of the workers into their unions.

The Parma Strike.

Then followed the strictly syndicalistic general strike of the agricultural workers in the province of Parma, which lasted a whole summer and culminated in a terrific conflict between workers and police on the streets of the city of Parma. This was indeed a memorable manifestation of Syndicalist vitality and faith. In order to endeavor to kill the strike, the police had decided to arrest all the known directing heads then in the local “(Camera del Lavoro,” or local Labor Council. But to enter the “Camera del Lavoro,” the police had to engage in a long fight against the resisting workers who, from the roofs of the adjoining buildings, stoutly defended their institution. Four years later, just before my departure from Italy, there could still be plainly seen the numerous bullet holes made by the deadly guns of the police on the facades of the houses of that working class district. This was the greatest of all strikes in Italy; and it therefore deserves to be given more space here, but I will only bring out the important fact that, at the end of the strike seventy-four of our comrades were arrested, and after a year in prison were brought to trial under the charge of having formed an association for the purpose of criminal transgression against the state.

Just as here in the United States there has taken place the famous trial of the I.W.W. of 1918,—so in Italy, in 1909, there took place the somewhat similar and celebrated trial aimed against syndicalists and Syndicalism. But with this difference: the jury there, contrary to the decision of the jury in the I.W.W. case here, at the end of the trial covering a period of two months, rendered a verdict of not guilty.

Only one man was condemned to one year’s imprisonment: this was Alceste De Ambris, general secretary of the “Camera del Lavoro” of Parma, the person who had done more than any one else to put life and vigor into this gigantic strike. He had been able to take refuge in Switzerland during the epic days of this revolt of the workers, and sentence was passed upon him in his absence. He is the same De Ambris—(strange irony of men and things!) recently come to the United States at the head of a so-called labor mission, made up of renegades like himself, and received with open arms and sponsored by Gompers and his lieutenants!

Without dwelling upon the many important episodes of Syndicalist activity in this necessarily brief sketch, we now come to the concluding chapter:

The “General Confederation of Labor” and the “Italian Syndicalist Union”

Up to 1907-1908, there did not exist in Italy any general organism uniting the labor organizations of the country. Such a general organization had often been suggested and discussed, and names proposed for it, but in reality it had never materialized.

The reformists established the “Confederazione Generale del Lavoro,” the “C.G.L.” about 1907.

The syndicalists were undecided for several years. Absorbed in their continuous struggles, they were unable to form for themselves a coordinated general organism of their forces. Finally, however, after several vain attempts to come to an understanding with the General Confederation of Labor, referred to above, there was formed during the early part of 1918, the “Unione Sindicale Italiana,” often referred to as the “U.S.I.” (Italian Syndicalist Union), which was greeted with the liveliest enthusiasm and the frank sympathy of the workers.

The technical structure of the “Italian Syndicalist Union” is similar to that of the I.W.W., and of the General Confederation of Labor of France; being based upon Industrialism. There is only one main difference in the two organizations, and that is that the “Italian Syndicalist Union,” in conformity with the traditional characteristics of the Italian labor movement, is largely based upon the local autonomy of the organizations. Italian labor is hostile to centralization, because of its marked tendencies against local initiative. It rebels against the idea of an excessively rigid discipline.

The main organism of action in Italy is still the local Labor Assembly, or “Camera del Lavoro,” which unites all the local labor organizations. But each unit of local organization is affiliated with the national industrial syndicate (or Industrial Union), in the case of organized industries, which in turn are affiliated to the Syndicalist Union, or general organization. However, the Industrial Syndicates have so far been considered more specially as organs of technical co-ordination. The “Italian Syndicalist Union” unites the movement in a bond of national and international solidarity, thus impressing upon it the character of unity, and also directs its movements of a general nature. But the “Camera del Lavoro” or “Labor Assemblies,” which might today be compared to ‘Workers’ Councils” of the various industries of a city or center of population, still function as the main organism of propaganda and of local action.

But aside from these details, the Italian Syndicalist Union is practically exactly the same as the I.W.W., be it in the principle of organizing the workers by industry; be it in the principle of repudiating politics and depending instead on the organized resources of the proletariat as such; or be it in its methods and tactics in action, or even on the premise of desiring “that the instruments of production and exchange be redeemed and administered through the industrial organization of the workers.”

Before the war, the organized workers of Italy totaled very nearly a million, altogether. A little over half of this number were affiliated with the General Confederation of Labor; the others are mostly adherents of the Italian Syndicalist Union. There were also a few independent organizations. For instance, the national union of railroad workers (an industrial union) has never been affiliated with either of the above. This union has had for years an average membership of 50,000; at certain periods a much larger number. It has always been directed by syndicalist elements, and though not affiliated with the Italian Syndicalist Union, for reasons which are too lengthy to record here, yet it has almost invariably shown a spirit of solidarity with said union.

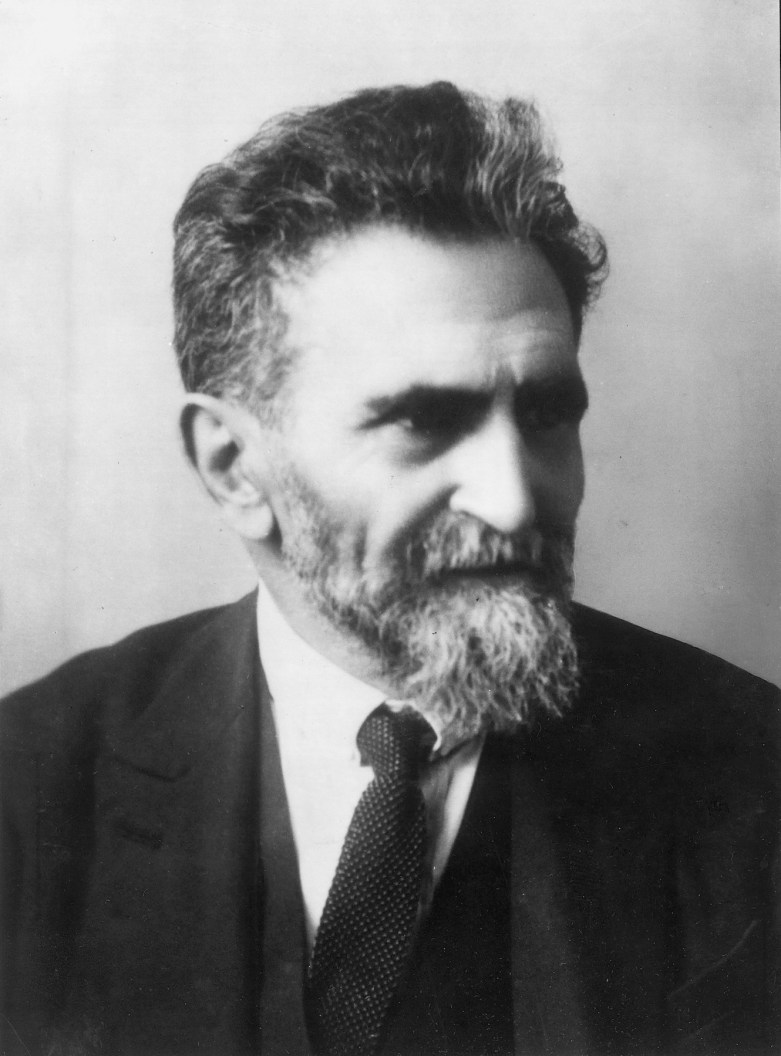

The general headquarters of the Italian Syndicalist Union were located at Parma at first, having for its official publication “L’Internazionale,” of which De Ambris was the vital force and soul. But when the war broke out, De Ambris and the elements surrounding him aligned themselves as in favor of the war, and so the General Council elected Armando Borghi secretary of the U.S.I. with headquarters at Bologna, and issued “Guerra di Classe” (The Class War) as its official organ, which continues to be published. The interventionists or prowar syndicalists have founded another organization, which we believe and hope may soon merge itself again with the Syndicalist Union.

During the European conflict, inasmuch as Bologna was declared as within the “War Zone,” Borghi was expelled and interned, first at Florence, and then in a distant small town of southern Italy. From these places he continued to direct the organization insofar as compatible with the difficulties of the war period. Borghi is a man of intellect and of action.

Returning to Bologna at the end of the war, he again took up his duties as administrative head of the Italian Syndicalist Union, aided by certain fellow workers which the war has spared, which demobilization has freed from military service, or whom a recent political and military amnesty has restored from prison.

From the last numbers of “Guerra di Classe” received here, we learn that complete propaganda and organization activity has been resumed.

As regards the Socialist Party, it is now quite strong and authoritative in Italy. It is directed by revolutionary elements, although it is considerably influenced by the fifty or more deputies, who are nearly all reformistic. The Party has always supported, more or less openly, the Confederation of Labor. Yet many of its members, and among them a few of its executives, have well known sympathies for the Italian Syndicalist Union.

The revolutionary socialists as well as the comrades of the Italian Syndicalist Union promise to carry on serious agitation in favor of the class war prisoners of the I.W.W. in this country.

In Italy, let us say in conclusion, there is a serious and a strong movement, and it is to be expected that we will soon hear the echo of great events. The Revolution appears outlined upon the horizon.

Note. Since the above was written we have received dependable information to the effect that the National Union of Railroad Workers is taking a referendum on the question of affiliating with the General Confederation of Labor or with the Italian Syndicalist Union. If the railroad workers syndicate joins the Syndicalist Union it will make of it the majority organization of the Italian workers.

(Translated by Frank J. Guscetti.)

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports. OBU was also Mary E. Marcy’s writing platform after the suppression of International Socialist Review., she had joined the I.W.W. in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1919-07_1_5/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1919-07_1_5.pdf