Published on the 20th anniversary of Ireland’s 1916 Rising, Brian O’Neill recounts the fighting in Dublin.

‘When Ireland Revolted’ by Brian O’Neill from New Masses. Vol. 19 No. 4. April 21, 1936.

This Easter week marks the twentieth anniversary of the 1916 uprising in Dublin. The rising has more than an Irish interest; for it was the first people’s revolt against the imperialist war of 1914-1918. Lenin was one of the few Socialist leaders outside of Ireland who understood its full significance. He hailed Easter week in Dublin as the beginning of the world crisis of imperialism and an indication that in the struggle of the workers for a Socialist world, the oppressed colonies would be their powerful allies.

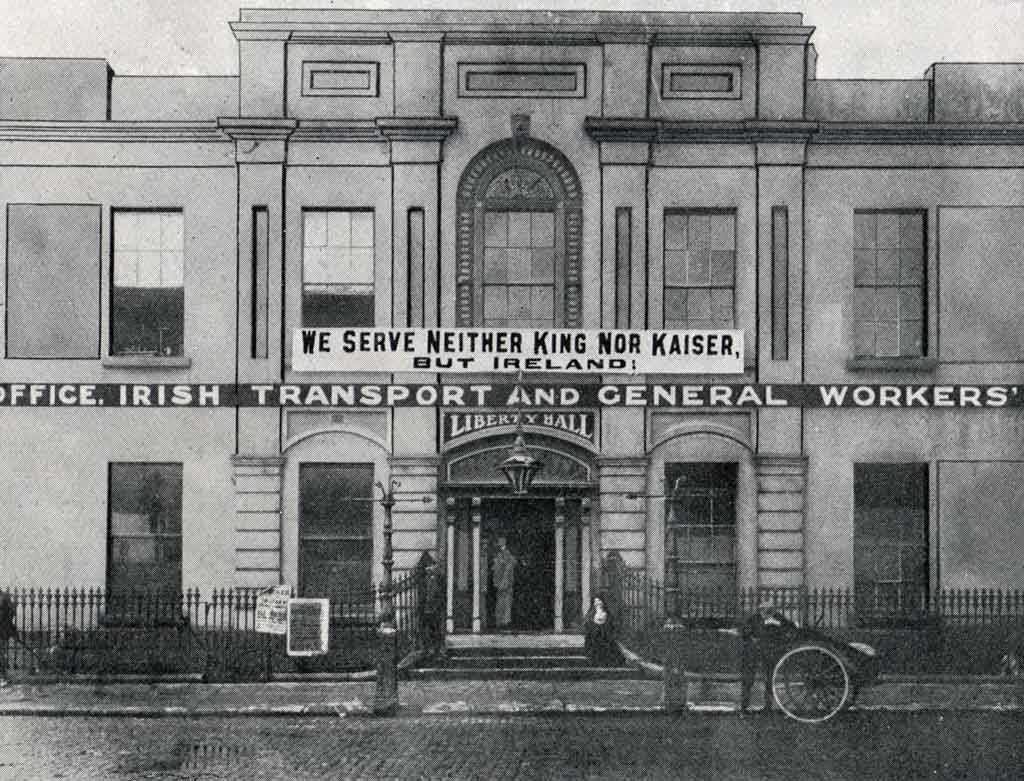

The rising began on Easter Monday, April 24, when little more than 1,000 men, armed only with rifles and revolvers, took possession of strategic buildings in Dublin and set up an Irish republic free of British rule.

Three streams of Irish thought were personified in the leaders of the revolt. Padraic Pearse, a poet of rare quality, represented the cultural renaissance of Ireland that had taken such forms as the Gaelic League, the Abbey Theater which “went to the people” for its subjects, and the so-called “Celtic Twilight” school, led by W.B. Yeats, John M. Synge, etc.

Thomas Clarke represented the militant nationalism of the Irish bourgeois democrats, organized, after the defeat of the Fenians in 1867, into the Irish Republican Brotherhood; and James Connolly, greatest of Marxians writing in English at the time, represented the working class and revolutionary Socialism.

The rising lasted from Easter Monday to the Saturday following. For two days the insurgents were supreme, but then the British government poured 20,000 fully equipped troops into Dublin, whose tanks and heavy artillery did great damage and compelled the Irish leaders to surrender.

The imperialists took a savage vengeance. Connolly, Pearse, Clarke, Sean McDermott, Eamon Ceamot, the poets Joseph Plunkett and Thomas MacDonagh and eight other Irish leaders were court-martialed and shot; Roger Casement was hanged in London, over 2,000 others were tried and deported.

Defeated though it was, the rising opened new phase in Ireland’s revolutionary struggle for freedom. Brian O’Neill, a brilliant young Marxian of the new revolutionary generation in Ireland, has completed a study of the Easter revolt which is being published in Dublin this week. The following chapter from his book describes the military aspects of the revolt and analyzes the political factor that was perhaps the chief cause of its defeat. THE EDITORS.

AT 9:30 on Tuesday morning Pearse wrote a statement to be issued in Irish War News, the little printed paper published from the General Post Office for the first and last time that afternoon. He wrote sanguinely.

“At the moment of writing the Republican forces hold their positions and the British forces nowhere have broken through. There has been heavy and continuous fighting for nearly twenty-four hours, the casualties of the enemy being much more numerous than those on the Republican side. The Republican forces everywhere are fighting with splendid gallantry. The populace of Dublin are plainly with the Republic, and the officers and men are everywhere cheered as they march through the streets.

Pearse was anticipating when he said there

had been twenty-four hours of continuous fighting. As he wrote he could hear the chatter of machine guns mingling with the crack of rifles from the south of the city; the second day was beginning briskly.

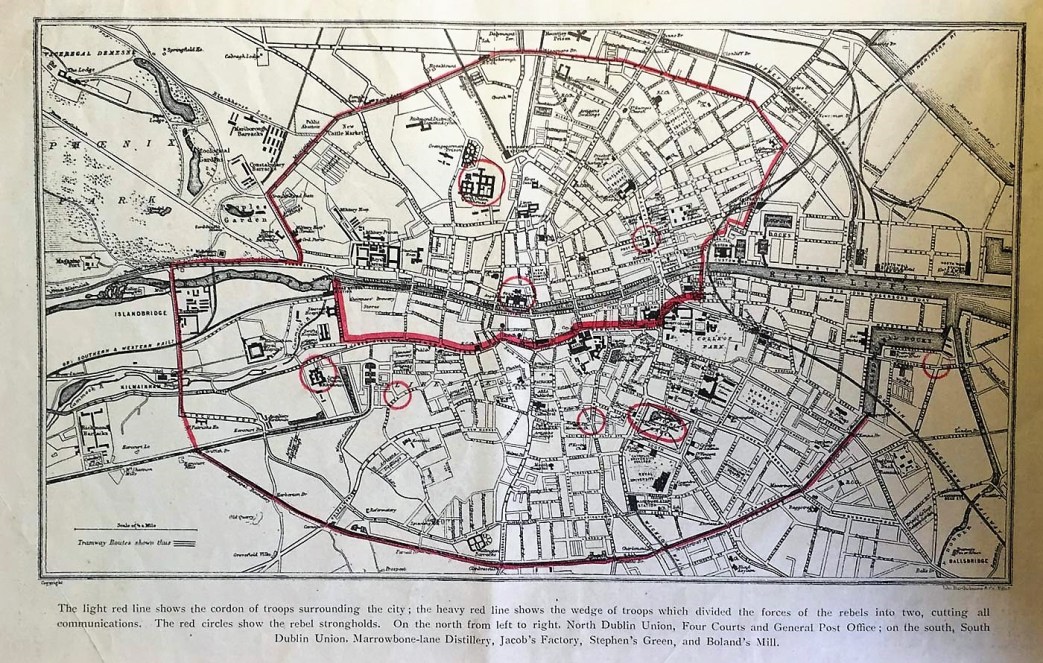

The British forces had evolved a plan by Tuesday morning. In the darkness, at 3.45 a.m., a troop train arrived at Kingsbridge Station from the Curragh, and with it Brigadier-General W.H.M. Lowe, of the Reserve Cavalry Brigade, to take command. General Lowe had already large forces at his disposal:

2,300 men of the Dublin Garrison. 1,500 dismounted cavalry of the Curragh Mobile Column.

840 men of the 25th Irish Reserve Infantry Brigade.

A battery of four 18-pounders of the Royal Field Artillery from Athlone.

Lowe decided to break through to Trinity College, in College Green. A small garrison held Trinity for the Government; with his position strengthened there, and a clear line of communication established from Kingsbridge and the Castle he would be able to move up troops into the centre of the city and cut through the Republican network. The College dominated the whole centre of the city.

Small bodies of British troops got through during the night and took up position on the roofs of the Shelbourne Hotel and the United Services Club, overlooking the north side of Stephen’s Green.

It had been a raw, cheerless night for Michael Mallin’s men in the Green. Sentries stood at all the gates; the remainder had spent the night in the summer-house or in the trenches dug under the shrubbery.

The original forty of the garrison had swollen to sixty-workers on their way home from factories and docks on Monday evening had walked into the Green to enlist. Some had never handled a rifle before. “Will ye look at the cut of himself!” chuckled the others as they looked at one of the new comrades. He was in a dress suit, coat tails sticking up and white shirt front pressing into the clay as he squinted along his barrel. A nearby hotel was looking for its waiter!

Just on dawn the storm broke. Bullets threshed the shrubbery and whipped the lake into ripples. The insurgents heard the rat-tat of a machine gun up above them on the roof of the Shelbourne Hotel, and Mallin drew back his outposts as three fell dead. The rifles blazed back, but could do little damage at such an angle.

Whether it had been intended to hold the Green permanently is disputed. If not, the wonder is that a night was spent in it, for a dozen snipers could rake the wide space from any of the tall buildings around and be secure from counter-fire. In any case, Mallin soon saw that the place was untenable and ordered its evacuation and the seizure of the College of Surgeons on the Green’s west side.

By 7 a.m. the College of Surgeons, a grey, staunch building impregnable to anything but artillery, was in the hands of the Republicans.

Later in the day General Lowe decided to clear the way from the Castle to Trinity College, for the handful of insurgents in possession of the City Hall and the Daily Express building held the seat of the Government in fee–a shocking position–and made it impossible for the British reinforcements to pass along Dame Street in large bodies.

A detachment of the 5th Royal Dublin Fusiliers was ordered to take the two Republican posts. The City Hall was cleared first, and a bombing party shook the Express building with their hand grenades. But the return fire was heavy, and a bayonet charge was ordered. Covered by machine guns, the Fusiliers advanced and burst into the building. There was fierce hand-to-hand fighting on the stairs, then the weight of numbers succeeded. “The dead bodies of 26 rebels were then found on the premises.”

A glance at the map of Dublin shows the importance of this victory. General Sir John Maxwell was justified in reporting: “It divided the rebel forces into two, gave a safe line of advance for troops extending operations to the north or south, and permitted communication by dispatch rider with some of the Commands.”

But the full importance of this British success was not seen yet, and at all other points the advantage lay with the Irish. Michael Mallin’s retreat to the College of Surgeons had strengthened his position. In the Boland’s Mill area Eamonn de Valera’s men were displaying splendid resource and mobility, and completely dominated the situation. The Four Courts and Jacob’s Factory were almost unassailed. An uneasy lodgment had been effected by the 3rd Royal Irish Regiment in the South Dublin Union, but the losses had been heavy–Major Warmington, the commanding officer, and his second in command were both among the fallen–and on the Tuesday evening the British decided to withdraw.

At the Republican headquarters in the G.P.O. hopes were high as Tuesday closed. Reports of risings in the countryside filtered through into the city; if only the country had not been stampeded by Eoin MacNeill’s order and would draw away some of the weight of the British forces from Dublin…

And James Connolly’s mastery of military detail was hearteningly impressive to the insurgents. The Socialist writer and agitator was proving himself the most outstanding man of the Rising. No outpost was too small to receive a note of guidance and encouragement. One such note, sent out on Tuesday, was found by the British later:

Headquarters,

Army of the Irish Republic, (Dublin Command) Date, 25th April, 1916.

To the Officer in Charge, Reis and D.B.C. The main purpose of your post is to protect our wireless station. Its secondary purpose is to observe Lower Abbey Street and Lower O’Connell Street. Commandeer in the D.B.C. whatever food and utensils you require. Make sure of a plentiful supply of water wherever your men are. Break all glass in the windows of the rooms occupied by you for fighting purposes. Establish a connection between your forces in the D.B.C. and in Reis’ building. Be sure that the stairway leading immediately to your rooms is well barricaded. We have a post in the house at the corner of Bachelor’s Walk, in the Hotel Metropole, in the Imperial Hotel, in the General Post Office. The directions from which you are likely to be attacked are from the Custom House, or from the far side of the river, from D’Olier Street, or Westmoreland Street. We believe there is a sniper in McBirney’s on the far side of the river. JAMES CONNOLLY, Commandant-General.

Such attention to military details was invaluable. But it is a pity that Connolly himself should have been overwhelmed by the military technicalities of the fight. He was the man of the Republican leaders who could have seen that an insurrection has two sides: it is a military operation; it is also a political struggle. Against the overwhelming military might of the enemy the insurgents should have brought only one weapon; mass support. “If only the people had come out with knives and forks,” de Valera is reported to have said in the last hours of the struggle, and the exclamation summed up the chief weakness of the revolutionary side.

Writers have drawn attention to the defects in the military plans for the Rising, but no weakness or false step was as disastrous as the insurgents’ chief omission. From midday on Monday until early Tuesday Dublin was in the hands of the revolution. But no printing plant was seized, except the Daily Express offices, and here the printers were turned out of the building at the point of the bayonet.

Had every available printing plant been employed through Monday night in running off revolutionary newspapers, manifestoes, leaflets in thousands, Dublin on Tuesday. would have rung with the call to the struggle and a substantial reinforcement would have been assured even if it were too much to expect the whole city to rise. The recruits who at all points on Tuesday were slipping through the British cordons to join the various revolutionary commands were an indication of the response a broadcast appeal might have secured.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v19n04-apr-21-1936-NM.pdf