In the effervescence of the arts that followed the Revolution, it was the theater, perhaps, that was most taken by the masses, and most transformed. In this chapter from Huntly Carter’s classic work on early Soviet theater, Lunacharsky is placed in the ‘center’, both politically and and as a reference, for the different schools emerging in an almost unrivaled period of human artistic creativity.

‘Lunacharsky’s Theatre’ by Huntly Carter from The New Theatre and Cinema of Soviet Russia, 1925.

The Centre Group comprises most of the theatres subsidised by the Government, and others that exhibit its general tendency of a compromise between the Left and the Right Wings, between the theory and methods of the vanguard of the workers and the rearguard of the old intelligentsia. This Group does not comprise all the subsidised theatres. Meierhold’s theatre is subsidised, but its theory and practice is different from those of the Centre Group. The Moscow Art theatre is subsidised. Its theory and methods also differ from those of the Centre Group. The one leans towards extreme communism, the other towards extreme individualism. The Centre is a combination of their moderate elements. In this group are aII the theatres and studios which are considered purely State theatres. These include the former imperial theatres in Moscow and Petrograd, also the Moscow Art theatre, the Chamber (Kamemy) theatre, the Jewish Central theatre, etc. The number of State theatres is less than formerly owing to economic conditions. At one time after the Revolution all the theatres in Russia were nationalised. But since 1921 some have been denationalised because the Government is not in a position to support them.

In the words of Lunacharsky, the People’s Commissary of Education:1 “A new period began in 1921 under the new economic policy, which has placed the cultural work in Russia in extraordinary conditions. For the first time our resources have been measured out to us. Now we have to adapt our life to a constantly elaborated and ruthlessly enforced plan of State organisation. The State is endeavouring to do away with grants in kind, and to estimate everything in money value, the better to control the workings of its economic apparatus” …“We have been obliged to restore the private ownership of the theatres, and in consequence the cultural level at which we maintained them during the first years of the Revolution has considerably deteriorated. The academic theatres are groaning for lack of support.” But against this must be set the statement that2 “the awakening of large sections of the public in Russia through the war and the stimulus of the Revolution is a fact.” The proletarian culture movement is spreading, and very largely affecting the theatre, as we have seen already. And there is considerable increase of public feeling against private traders, such as shopkeepers. On the whole, a return under improved economic conditions to the communist path opened by the Revolution is not improbable. At any rate, all the theatres, whether privately managed or otherwise, are under the constant observation of Lunacharsky, and the Department of Education, linked with theatrical productions, is still in existence. Whatever be the fate of the other parts of the educational system during the present period of the Communist State, this part will be carried on. For this reason, if for no other, the building-up and the work of the cultural-educational theatre as conceived of by the State officials demand to be considered.

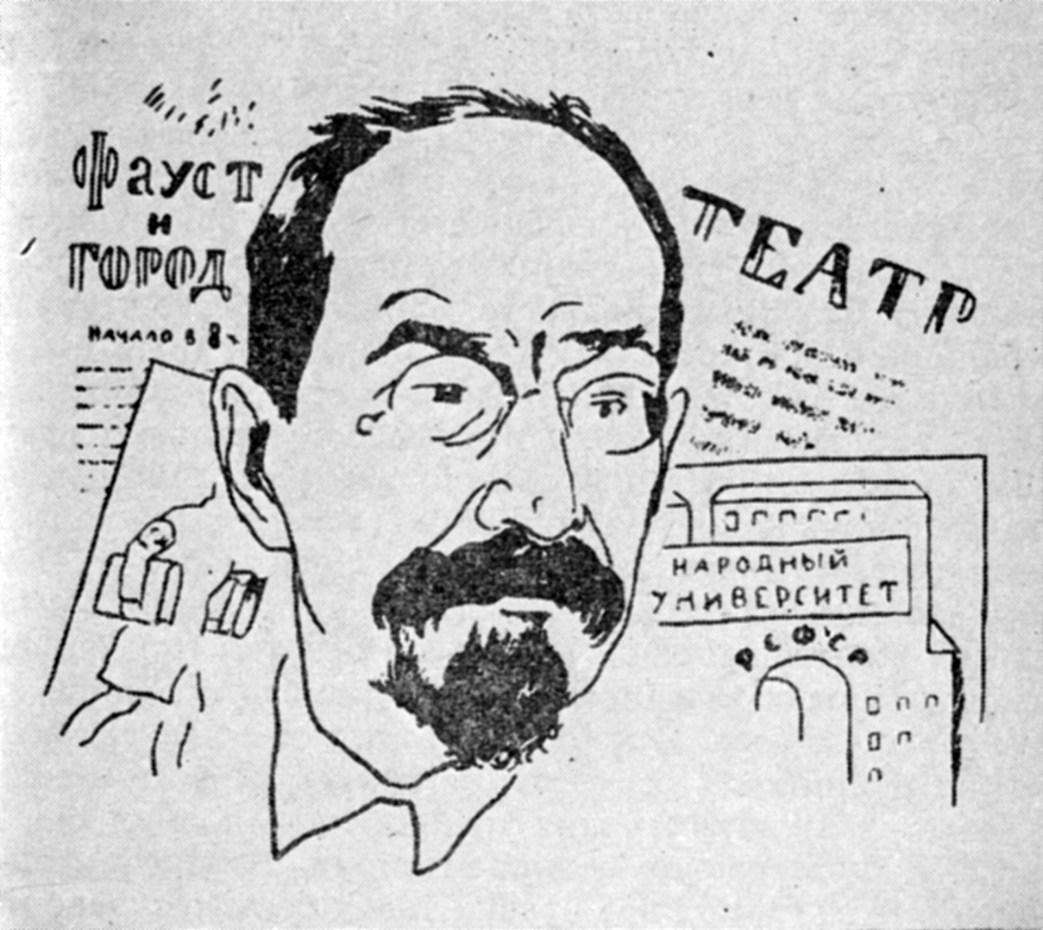

The Centre Group theatre may be said to be strongly influenced and shaped by the ideas and ideals of Lunacharsky, just as the Left Group theatre is by those of Meierhold and the Right Group theatre by those of Stanislavsky. But it reveals a great difference in manner and matter from either. In matter, Meierhold and his followers are as revolutionary as communism; in manner, as evolutionary as industrial science. They assume that the workers want to use the theatre for the purpose of constructing a working model of their new industrial world for which they are fighting, and they are helping them to build it as a rather wonderful machine of which the workers are the conscious parts. This is the new constructive stage technique. The worker-players are seen as parts of the machine, expressing its forms and movements as far as possible. The scenery, too, is designed to express industrial forms, highly condensed to fit the new theory of representation. The whole is intended to suggest that the mechanisation of industry, such as will take place in the New Russia, is a necessary introduction to the Leisure Life implicit in communistic theory. Stanislavsky’s matter and manner are as revolutionary as stagecraft permits. He has nothing to do consciously with political or industrial propaganda. His sole business is with the propaganda of his own theatrical ideas, as may be seen by turning to the chapter on the subject of Stanislavsky’s theatre. Taking these differences into consideration, as well as the fact of Lunacharsky’s influence, it is permissible to speak of the Centre Group theatre as Lunacharsky’s theatre.

We have seen that with the Revolution, the Soviet Government assumed control of all the theatres, the privately owned as well as the old imperial ones, and that some months later, in the person of the Minister of Education, Lunacharsky, they concentrated a good deal of their efforts at educational reform upon the theatre, hitherto devoted to the dissemination of bourgeois ideas. In the early days of the Revolution the idea took root that the theatre must be made not only a popular institution—that is, popular in the sense of being owned and managed by the people, but a place wherein the people might amuse themselves by absorbing communism and by playing at the realisation of communistic theories. Yet the changes prepared by and actually effected by the Government officials under the leadership of Lunacharsky were much more moderate and rational than those effected by certain men of the theatre who leaned heavily on the extreme Left. Indeed there is no doubt that the attitude of Lunacharsky and his educational party towards the theatre was as reverent as that of the ancient Greeks. There are positive resemblances between the State conception of the new Russian theatre and the conception of the ancient Greek theatre. Both rest on the idea of a popular theatre, both imply socialisation of the theatre, both are concerned with cultural-educational centres, and both are bound up with the establishment of a one-function theatre. By a one-function theatre is meant a theatre which stands for public service alone, not for public service and acquisitive gain, as is the case with the commercial theatre.

There is also an important difference to be noted. It is this difference which entitles the present Russian theatre to be called new. It deserves to be strongly emphasised because it really gives direction to all other differences between classical and contemporary—for instance, the German Neue Freie Volksbuhne—popular theatres. If we study the ancient Greek and modern German theatres we shall find that the Greeks and the Germans are concerned with the problem of bringing the theatre to the people as a whole, and vice versa irrespective of class, but in such a manner that the working class (or masses in Greek days) shall derive as much benefit from its educative and recreative power and importance as the middle and upper classes. Thus, the poorest person in the community would be assured of as ample a theatrical experience as the wealthiest one. But they are not concerned with the problem of bringing the stage and the drama to the people, and vice versa. Both the stage and the drama remain isolated from the people, the one as the playground of deputy players, the other as the product of deputy playwrights. They are, in fact, isolated in an aristocratic, intellectual, individualistic, aesthetic, or some other way from the people themselves. It is true that there are various projects for bringing the audience into the performance. But these do not affect the contention. The attempts to mix the people with the production, which Max Reinhardt has made, do not remove the isolation between the stage and the audience, the spectator and the professional player.

The fact remains that in early Greek times and during the Free theatre movement in Europe, nothing was written for the people or by the people. Plays were written by the intellectuals (or intelligentsia, as they are sometimes called), by the educated middle class, and a few by the upper class, who experienced life from a far different standpoint from which the masses experienced it. All through the Free theatre period, which sprang up in Germany many years ago and continued till the war stopped it, the intellectuals let themselves go on their favourite topics with a vengeance. Science, politics, psychology, biology, pathology, criminology, spiritualism, libertinism, and indeed all the intellectual problems of the modern world were dished up one after the other, and succeeded in putting a faint glow of interest in the minds of small cliques of intellectuals. But they left the masses icily cold. Even the drama of the dregs with which certain playwrights sought to interest the middle and upper classes in the hardships of the lower classes, was no better. It was simply composed of high-brow views, and opinions on low-brow psychology and economics. The writers of this stuff proposed to make accessible to the lower classes a vision of their struggle which the lower classes could not have, and to win for their plays an audience for which they were not meant.

Much the same might be said with regard to stage-craft. No better result was attained when frenzied reformers tore down the act-drop, removed the proscenium, and made the stage and auditorium one. They did not achieve the necessary unity. They did not put the masses in the front of the stage. All they did was to continue to advance those personalities who embodied intellectual problems and outlooks which have no value at all for the masses. Thus, though the action-place was pushed into the auditorium and the players made their exits and entrances, and moved freely among the spectators, even sat beside them and took them prisoners with the pungent odour of grease-paint, isolation remained. Every time the reform theatre was filled, and this may be stated as a general rule, it was filled with an audience two-thirds of whom were not active participants in the action of a play which was truly an unfolding of their inner life as they themselves experienced it, players in a dramatic experience of their own. They were either eager to watch a theatrical exhibition that flattered their intellect and vanities, like a present-day stage discussion, or curious to witness that sensationalism of matter and manner, especially scenic, which unfortunately has, of recent years, been allowed to enter the reform theatre disguised as theatrical advance.

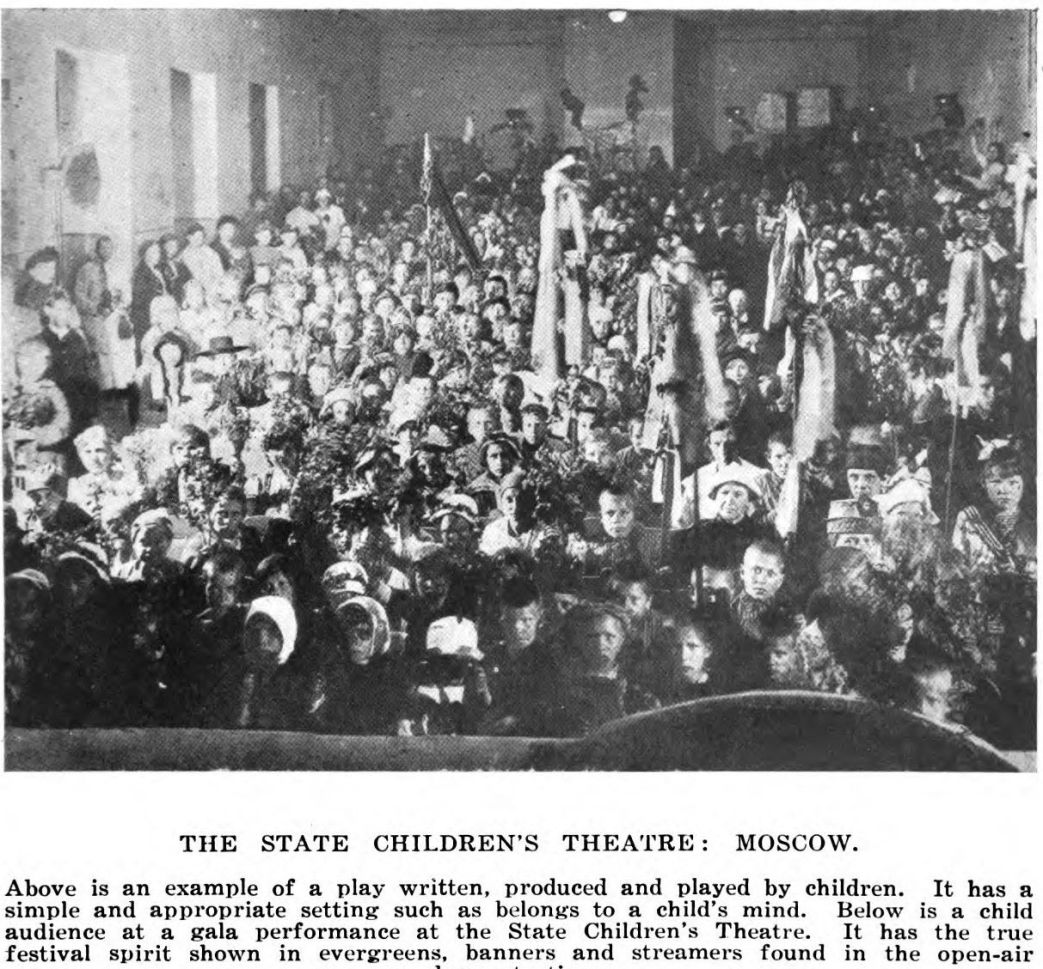

The builders of the new Russian theatre are concerned with a far different problem, which may be called the new thing in the theatre. It is the problem of bringing the theatre to the workers and the workers to the theatre in such a way that they become a functional part of each other. The theatre must no longer resemble a deputy human body which goes through all the business of life while the real body sits idly watching the process. It must be the real body composed of those engines whose secrets still elude the theatrical biologists, the psychologists, and the physiologists, who, with all their skill, never succeed in quickening the human body and soul and keeping them together and alive in the theatre. The crowning glory of this real body is the brain, with its delicately adjusted mass of “operators and wires,” so to speak, forming the organising and administrative master-contrivance of the body. Given a satisfactory solution to the problem the world will get for the first time in its history a theatre which is a masterpiece of functional correlation and social co-operation.

So the task to which Lunacharsky as a representative of the Soviet Government was committed was that of planning a theatre from which everybody and everything is excluded except the workers and their own dramatic experiences quickened by communism. It must contain no personalities, except the mass one, and no deputies. The people are to take the stage, and to let the world see them unfolding their wings under the communist touch, and the stage is to take the auditorium, as it were. This means that the whole theatre must be turned into a stage, and all the workers will be players. Which, when it is done, will be merely a demonstration of the truth of Shakespeare’s observation that the world’s a stage, and man and woman are merely players.

The original plan was a working-class or mass theatre springing directly out of the Revolution, and embodying those principles for which the Revolution was fought. Its aim was to encourage the workers to become their own authors, producers and actors; to exalt the anarcho-mass where the anarcho-individualist had been too long; to replace the culture of the cultured by the culture of the uncultured; in short, to destroy everything belonging to the bad old order in order to make way for everything belonging to the good new order.

Time and circumstances have interfered with the plan. The result is that instead of being realised by one group of organisers and administrators representing the Government, it is being realised by three groups representing the three parts into which the Government may be divided, Left, Centre, and Right. The three may be said to have a common plan, but not a common method. So the building of the workers’ theatre occupies their attention in different ways. On the Left very deeply, in the Centre more soberly according to considerations of State, on the Right only as far as the irresistible current of events compel. The Right would like to break away from the working-class movement and return to bourgeois idealism. But a current has decidedly set in in the direction of a new working-class society. This is too strong for the Right, which must therefore either go with it or be drowned.

Each, then, is making its contribution to the original plan, each has building materials of its own. From the Centre Group comes the cultural-educational bricks and mortar necessary to awaken the class-consciousness of the workers, and to reveal to them the meaning and significance of their own ideology. The preparation for this section of the structure has been on well-defined lines of destruction and construction of a more or less traditional character. The latter is inevitable owing to the particular temperament, training and physique of the master-builder of the section. Lunacharsky, whose characteristics and contribution to the new theatre are described elsewhere, is mainly concerned with the theatre’s cultural-educational and civic purpose, and therefore reveals a traditionalist or conservative tendency by selecting masterpieces and methods of the past, preferring, of course, those with a present political and social meaning and significance. This in its way exercises a formative influence upon the Russian character, which, as Lunacharsky wisely understands, can only be built up in the new way by starting at the foundation of primitive instincts, impulses, and emotions. It is also his method of theatre building.

Lunacharsky’s plan, as originally conceived, was to build a cultural-educational theatre—a theatre devoted to the cultural development of the workers, and to the making of citizens. Moreover, it was to be a theatre in whose work only the workers and their sympathisers shall take part. The plan was not an easy one to realise. It meant removing the existing human and material cultural resources and replacing them with others which were practically unrealised. It meant indeed ridding the theatre of its bourgeois cumber, and leaving very little except an empty structure to be adapted to the new purpose. Furthermore, it meant that this old and impossible structure, composed of all the established playhouses, must be used in an entirely new way. For there was no time or money for the purpose of destroying it, as a well-known Italian actress once demanded that the theatre should be destroyed, and building an entirely new one capable of fulfilling the function of a theatre of Popular Culture based strictly on Marxism. Properly speaking, the theatre demands a new form if it is to be an instrument for initiating the workers into the truth of Marxism. The old or existing form is a bourgeois or commercial one. The man who put a wall round the stage in Elizabethan times did so to make money. Now every brick proclaims aloud a bourgeois ideology. Every brick of the conventional theatre is reactionary, so to speak. The same objection applies to the millionaires’ palaces in which the Russian workers have established their clubs and stages. They embody the millionaire reactionary spirit. They breathe it on the workers, and probably exert as powerful an influence on them as disembodied spirits are said to do on the unsuspecting. Any psychologist will tell you as much.

There is no need to enlarge on the difficulties. They must be plain to everyone who has the slightest notion of what Russia has gone through since 1917. In spite of them, the building of the cultural-educational theatre has been upon well-defined lines of destruction and construction. Facts to prove this are fairly numerous. Among them are the following taken from official sources.3

There was, as already stated, no change at first. The earliest policy of the Soviet Government was one of non-interference. They left things alone, to be developed by circumstances.

The People’s Commissary of Education, Lunacharsky, is himself a writer and playwright of considerable reputation; and he realised fully that it is necessary, in art, for any new movement or general tendency to develop its strength in free combat and contrast with the forms and philosophies of art that it is striving to supplant. The Commissariat for Education, having taken over the nationalised theatres, brought them within the reach of all classes of the community. It gave over into the hands of the theatrical workers themselves the task of choosing the plays, ballets, and operas to be performed. It gave them complete control over method of production as well as repertory. And then it left the various movements to develop or to die without interference or constraint.” It should be said that this choice and control was subject to the approval of Kel’s Committee, to which reference has already been made.

The first essential change in the making of a popular culture theatre was that of converting the established theatre into a free or one-function theatre by the elimination of money and the introduction of tickets. The commercial idea—the idea that the theatre was originally built and supported by gold, that gold purchased everything—plays, actors, scenery, had to be overcome, and its evils swept away. So the motive of profit was eliminated as far as possible. Regarding the ticket system, we are told “in some theatres almost all tickets—at one time, at least—were distributed through the trade unions. In others the Government departments issued the bulk of the tickets to their employers, many of whom, of course, were from the better educated sections of the people. At one or two theatres almost all the tickets were sold in the ordinary way, but the prices were very low, and the theatres received supplies, and, if necessary, a subsidy from the Government.”

The essential second change, that of making a popular culture audience, was brought about by the first. “The theatres (owing to the free and low price ticket system) were certain of an audience; for the Russian people are intensely appreciative of art in any form, and no war or revolution could so occupy them as to make them lose interest in the stage.”

The third essential change, that of making popular culture players out of unpopular materials, took place as follows.

“The Russian stage inherited from the Tsarist regime a peculiarly cultured class of artistes. The theatre used to be dominated by the nobility and the ‘intelligentsia’—a class peculiar to Russia in its aloofness from the rest of the people and the vitality of its artistic interests. Commercialism did not deeply affect the Russian stage; the ‘revue’ was not known there; the average Russian theatre was as different from the average British or American one as the ‘corps de ballet’ is from the ‘beauty-chorus.’

“It might have been expected that the Russian actors and actresses would have chosen to go on playing the tragedies that showed the soul of Russia before the Revolution, the comedies inspired by Parisian influences, or those dramas of personal relations, ironic and rather bitter, which had made the reputation of the great Russian playwrights of the last century, men like Tchekov and Andreiev. But all actors know and desire the response of an audience; its imaginative sympathy helps them not only to finer work, but to the fullest enjoyment of their work, while even the greatest play seems to fall flat if the audience is out of tune with it in thought or feeling. And it was this responsive sympathy that the Russian players set themselves to arouse.” Here we have the new actor as the result of the new audience. Apparently the appeal to public feeling is one whose response it is not easy to despise. A good many actors left Russia soon after the Revolution rather than appear in revolutionary plays. Those that remained, of course, preferred to appear in plays that called forth sympathy from the audience.

So we come to the fourth essential change, the making of popular culture plays. As regards this matter it seems that at first the type of play was not changed. The difficulties attending the Revolution and immediate after events “forbade any attempt to produce new plays and made impossible the growth of any coherent movement.” But later, when the distribution of theatre tickets had been organised, and the theatre knew what sort of audience to expect, when the material difficulties of supply and lighting had to some extent been overcome, and all those whose work was in any way connected with the theatre could rely on some sort of rations and supply of necessities—they were given certain privileges as to housing and a ration of food higher than that of the majority of the people in the city—when this had been achieved, the artistes and those interested in the artistic side of the theatre began to get together and form their own managing committees, repertory committees, and “critical councils.”

With these theatrical “soviets” at work, there followed a process of elimination. In the life of post-revolutionary Russia there was pity and terror enough, and all the stark material of tragedy—except despair. Those who despaired of Russia were of no use to her in a time of reconstruction and struggle; some of them left a country whose development they could neither help nor understand; the remainder ceased to affect its life in any way save as a dead weight to be carried, so many mouths to be fed. The men whose lives lay in the open fields or amongst the great machines, into whose hands the future of the country had passed, had no sympathy with the drama of the ‘middle emotions,’ the psychology—or pathology—of the discontent in little and rather meaningless lives. A high wall hid them from the shadowed paths of ‘the Cherry Orchard,’ and its blossoms were too brittle for the times in which they lived. The first suggestions and experiments took the form of melodrama. It was felt that the naive and exaggerated emotions, the action and the incident of melodrama would suit the new audience. Later, and for much the same reason “came romantic plays.”

The fifth and final change was that effected by the changes in the population. The revolution had affected every side of life; the whole country, its philosophy and its religion, its conception of the present and its hope for the future was changing. And, of course, as time went on the workers would put on Afferent characteristics and exhibit different moods harmonising with the different trends of thought and action. It could not be expected that they would remain as stationary as in Tsarist times.

In poetry and literature we have an instance of changing periods. In its early days the Revolution presented itself to many established and unestablished authors who had remained in Russia in a romantic garb. In the old days they had sung about it, even invited it to come. When it came they were disposed to follow the example of Alexander Blok, the well-known poet, by regarding it as “holy banditry,” and investing the revolutionaries with the nimbus of a Saint Bandit whose purpose it was to deprive Russia not of its great national virtues, but of its foulness of life. They placed Russia, indeed, on the crest of Calvary, crucified between two robbers. The task of the bandits was to take down the body and conduct it with fitting ritual to a deified resurrection. As a consequence of this mood, poets and other authors poured forth a lot of pseudo-revolutionary stuff designed to clothe these quaint romantic ideas.

The romantic period was followed by a realistic one. In the first days of the Revolution the poets—symbolists, futurists, imagists, etc.—while the novelty was upon them, entered their ivory tower and sang of deliverance and the rest of it. But presently came civil war and famine and economic privation, which overturned their romantic tower and left them struggling for existence with the mass of the people. So in the first year of the Revolution, poets and authors became split into two camps. The pseudo-revolutionary ones—Blok, Kuliev, Andreiev, and others—who could not change their conception of the Revolution, turned tail and fled. Others who had caught the true significance of the Revolution remained and became associated with the new body of workers in forms of social service, including the theatre. Caught in the wave of real events, they very quickly substituted realistic-expressionism for false romanticism.

Then came a third period when the workers and their cooperators, finding themselves released from the overwhelming exactions of civil war, turned to the serious but more congenial business of rebuilding industrial and economic life. The poets and other creative minds among them very quickly conceived a new form of expression suited to the main purpose. To this they gave the name of “constructivism.” In the theatre the aim of “construction” is to replace the principles of painting by those of engineering. The effect of “construction” is to indicate not merely an end to be attained but a certain suitability in the means employed to attain the end. The idea has caught on, and to-day it is working through all the new institutions, particularly the theatre. The tendency is fully considered in the chapters on the various theatres.

These “periods” reflected themselves in the theatre of cultural-education in spite of its traditional attitude. Lunacharsky has never welcomed violent reforms in plays, acting, scenery, etc., preferring matter and manner that appealed to the primitive instincts of the new audience to high-brow experiments which were above its head. His own contributions have been of a traditional character, of course, strongly touched by his Marxian preferences. Two, at least, of his plays, “Cromwell” and “The People,” exhibited new ideas and theories in old forms. “Cromwell” was an attempt to read up-to-date revolutionary tendencies in the Protector, “The People” was an epic drama in spectacle form. Its five acts covered the history of the world from “before religion” till “after revolution.”

These plays are said to have widened the split in the camp of poets, painters, and others concerning the art forms of the future. The revolutionaries refused to have anything to do with the pre-occupation with form manifested by the classicists. They stated their belief that form did not matter; content was the thing. If sufficiently important, it would put on its own form, expressionist, futurist, or any other. The classicists would have none of this. They stood for the “essential traditions of the theatre intact.” They contended that the theatre stood for form. It was outside social reform, politics, and the rest of the dreary pulpit stuff. It was sufficient unto itself. In their view the task of the theatre was to “influence and to educate the masses of the people to an appreciation of the great work of the past, the work that had lived. Only when the people understood, and were in sympathy with past achievements, could any group of artistes go forward, with the certainty that their work would receive intelligent criticism and appreciation, and with the inspiration of the active and creative understanding of their audiences.”

Of course, against this went the obstinate opinion that politics were the life blood of the New Russia. They were absolutely necessary to the development of the people. It was the changes wrought by politics on the life of the people that mattered. Unless artists and writers could take their eyes off the past and fix them on the present; unless they could share the sacrifice of the people, could live their lives, share their dreams and fears, they would be of no value.

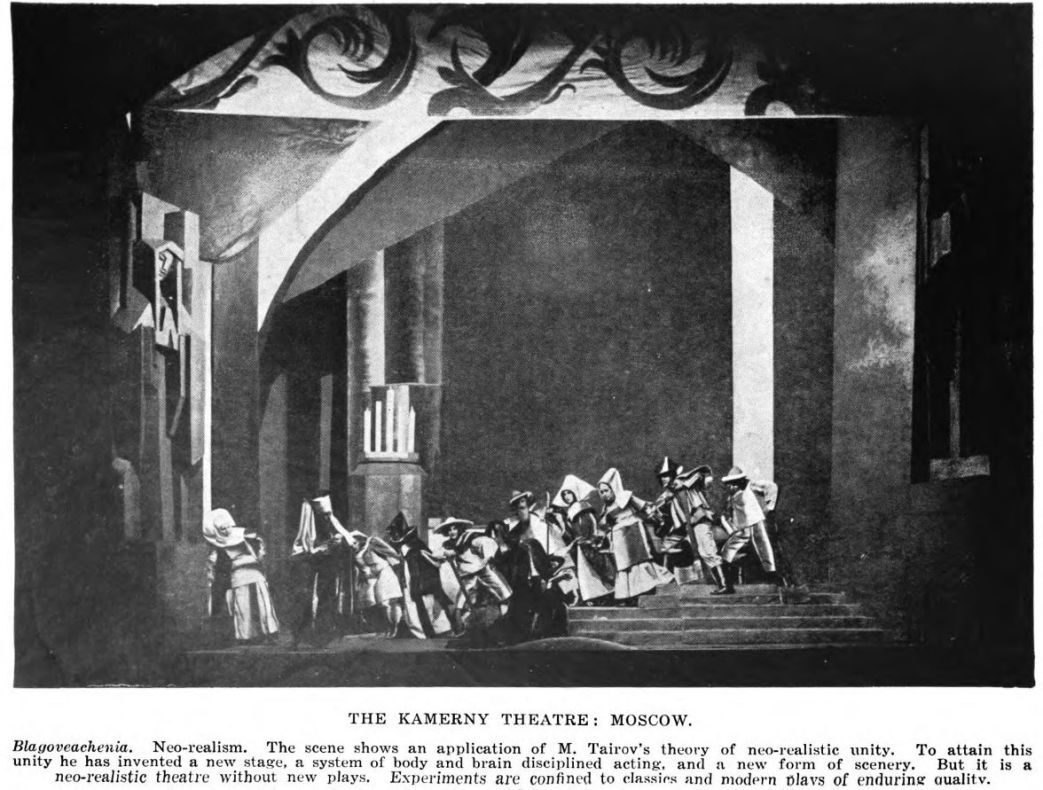

This was sufficient to modify the classical current and to cut off certain historical streams as shewn elsewhere. And it opened the cultural-educational theatre to the new streams of stage-craft, realistic-expressionist, and constructionist, which kept it abreast of the times. A very good instance of Lunacharsky’s theatre going through this metamorphosis, so to speak, is afforded by his defence of the production of “Carmen” at the Moscow Art theatre. It appears that he found himself in radical disagreement with the views on this production of the dramatic critic of the “Isvestia.”4 Accordingly he explains the production from his own point of view.” After referring to the needs and sufferings of the theatre staff working under extremely difficult conditions, he asks, “What does ‘Carmen’ give?” He examines the path of stage-craft in the European theatre, and finds it has left the “left wing revolt against ‘mimicry and realism,’ and has taken up a middle position by compromising with the two points of view. How does this agree with the task of the theatre? What is the task of the theatre? To him it is not photography. It is the translating life freely into theatrical forms.” He is obviously referring to a form of expressionism. With “pure expressionism” he will have nothing to do. The aim of “pure expressionists” is to break completely with reality (meaning actuality). Like all creative artists, they seek and are entitled to make their own world. But it is a formless and absolutely incomprehensible world. “It has nothing in common with humanity.” These pure expressionists say nothing because they have nothing to say. He glances at the attempt of Tairov, the director of the Moscow Kamerny theatre, to establish a non-representational form of expression, and dismisses It with a gesture of impatience as “beyond all limits of absurdity and paradox.”

Having cleared the approaches to ‘Carmen’ in this way, Lunacharsky fires off a definition of realistic-expressionism, the thing which in his belief the stage needs nowadays. It is a “realism that is native and familiar to us in all its determinants, and at the same time is unusual, constructed, so to speak, entirely in the new harmony, at the pitch of modern ideas and emotions.” Dealing with the production itself he remarks, “It was not by accident, if perhaps unconsciously, that the Grand theatre chose “Carmen” for its first step in the direction of operatic reform. This opera lends itself better than any other to impressionist realism, for that was its form when it left Bizet’s hands. It is, therefore, ridiculous to reproach Fedorovsky and Sanin (the decorator and producer) for not giving us Spain as she is. They give us an idealised Spain, the Spain of Bizet, and one must be simply blind not to feel the power of Fedorovsky’s decorations for the first, second, and fourth acts. Thanks to these decorations, the opera moves before us like some beautiful and terrible creature—like a tiger. It was, of course, difficult to put the same power into the music, instrumental and vocal, and get from sound the same compelling impressions as from colour. Nevertheless harmony was achieved; the interpretation carried us out into the Mediterranean sunlight—Spain, mid-day.”

As for Sanin, “he took this melodrama and made it more and more tense from situation to situation; the meetings on the piazza, the sun and the crowds, the squalid tavern, and the old tunes of the past; then the tearing storm of passion. Then came the sun again, the singing, holiday-making, sensuous crowds—and the murder.” Fedorovsky’s costumes, too, “displayed astonishing richness,” beyond anything seen even in Paris. In short, realistic-expressionism achieved amazing effects in colour, sound, movement and emotion. The production of “Carmen” may be reckoned among the best given at the State theatres. Productions at the Small theatre and the Big theatre, Moscow, the Mariansky theatre, Petrograd, and other subsidised theatres could be described in detail, but nothing would be added to the information contained in Lunacharsky’s explanation. I remember seeing a performance of “Lohengrin” at the Big (Bolshoi) theatre. It struck me as being one of the most picturesque productions from the realistic-expressionist point of view I had ever seen. It was a magnificent example of stage pageantry designed to reproduce the legendary atmosphere in which the opera is set. The scenes passed before one like a succession of old German paintings, rich in form and colour, and composed of masses of early German figures, knights, soldiers, dames, children, citizens, etc., in impressively striking costumes, and moving amid a perfect forest of halberts, spears, bannerets, and symbolical devices of all kinds, and against a rayonnist background, that is, a background resembling the brilliant multicoloured rays of the sun. The handling of the crowds in the big scenes was certainly masterly. And the decorative effect of some of the scenes, especially the last act with its arrangement of big coloured curtains with the centre divided off into a canopied chamber containing a splendid coloured couch, was extremely effective. But the production was not beyond criticism. On the whole, it was too much of a kaleidoscopic mass, lacking simplicity, unity and continuity. The coloured light that was thrown on the scenes was too diffused. It embraced everybody. I did not like the new method of putting the principals in turn in the centre of the stage upon a raised platform, where they resembled nothing so much as speakers at a political meeting. Still the whole thing was breath-taking, and, added to the gorgeous and harmonious interior of the Big theatre, no doubt it fulfilled its purpose of exercising a powerful influence on the plainly dressed, but enthusiastic audience that packed the mighty auditorium from floor to roof.

If stage-craft advance in the form of realistic-expressionism set its mark on “Lohengrin” something even more revolutionary appeared in the scenery for Wagner’s “Rienzi.” Here a treatment that was more Left wing than the home of classic opera had ever known, presented itself in the form of the circus ideas with which the Proletcult theatre had definitely associated itself. The scene, as designed by the painter, Yikylov, was shaped like a circus-arena with steps at all angles and all levels, with suggestions of a trapeze and hoops and the rest of the objects and agents of circus representation. What these aids to opera really mean is not quite clear. Probably they are meant to enable singers to make their highest flights as song birds. In the dramatic theatre they are considered essential aids to acting. It may be that the introduction of the circus to the opera is by way of a decorative appendage, although the new men of the Russian theatre have sworn to rid the theatre entirely of “decoration” as such. Or it may be that need of modernising the opera in accordance with the more natural and reasonable taste of the time, by removing cumbersome and idiotic machinery devised by Wagner and the pretentious and unreal effects devised by other composers and producers, has opened the door to other extremes. At any rate, side by side with the retention of classical operas has gone reforms of a sort. These include the nationalisation of music, the repopularisation of folk music under Lunacharsky and Laurie; the emphasising of communist elements in operas in Moscow and Petrograd, and the selection of operas that make an appeal, however remote, to the revolutionary spirit. Does not “Lohengrin” do so? That is what some of the war-time critics of Wagner meant when they accused his music-dramas of being responsible for the Great War. Further, there has been the reconstruction of the State orchestra by Kuper and Serge Kassewitsky, a renaissance of the State Ballet, and the introduction of a new system of musical education.

Many reliable foreign eye-witnesses have testified to the quality of the work carried on in Lunacharsky’s theatre. Seeing that this evidence is reasonable, we may set beside it the words of Paul Scheffer, editor of the “Berliner Tageblatt,” that “Moscow is the Mecca of theatrical forms of art.”

NOTES

1. “Culture in the Soviet Republic.” A. Lunacharsky. “Manchester Guardian” Reconstruction Supplement. July 6, 1922.

2. Paul Scheffer. “Manchester Guardian” Reconstruction Supplement. July 6, 1922.

3. “Russian Information and Review.”

4. Moscow Isvestia June 2nd, 1922.

For a PDF of the full book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.166125/2015.166125.The-New-Theatre-And-Cinema-Of-Soviet-Russia_text.pdf