Harry Haywood critically evaluates the Communist Party’s role in defending Black miners’ interests during the wave of insurgent miners’ strikes led by the Party’s National Miners Union in 1931.

‘Lessons of the Miners’ Strike and the Tasks of the N.M.U. Among Negro Miners’ by Harry Haywood from The Daily Worker. Vol. 8 Nos. 240 & 241. October 6 & 7, 1931.

I.

In evaluating the work of the Party and National Miners Union in the recent tri-state Miners Strike, particular attention must be given to the work among the Negroes.

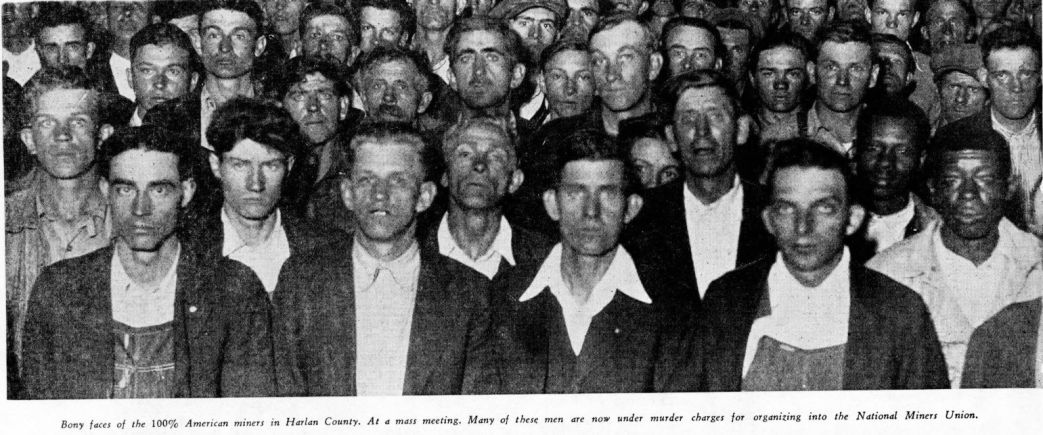

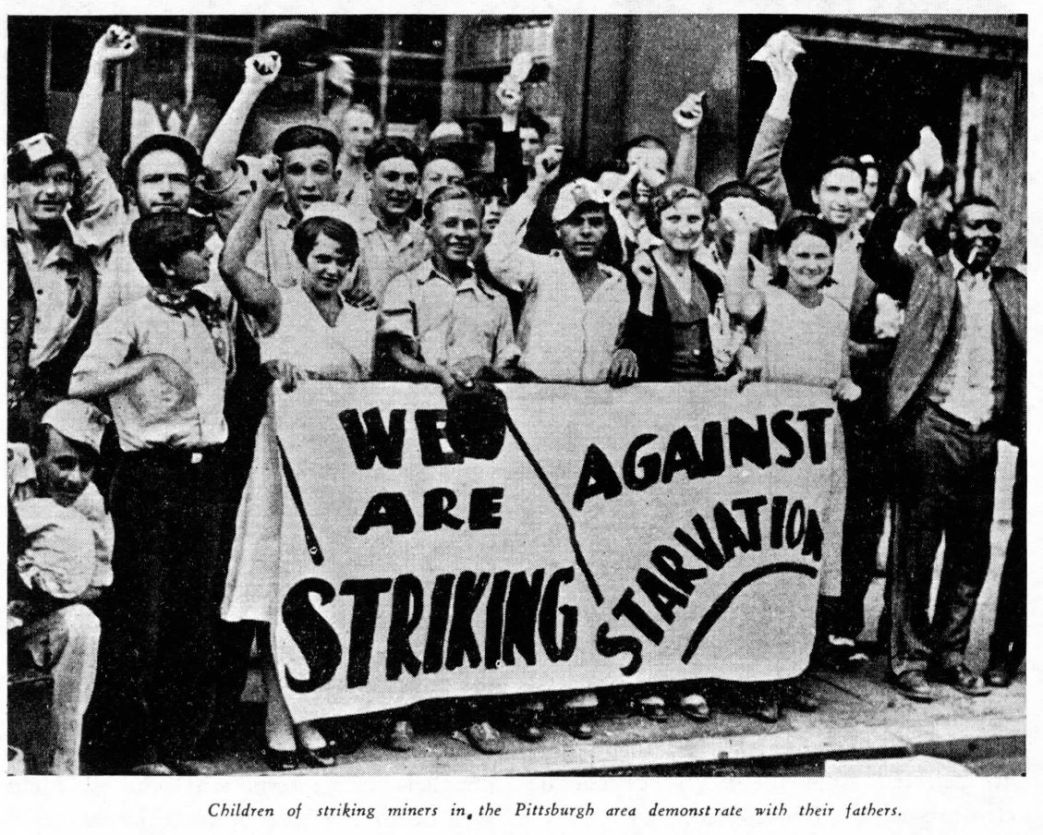

One of the most outstanding achievements of the strike was the splendid spirit of solidarity manifested between Negro and white miners. Approximately 6,000 Negro miners were involved in the strike (nearly one-fifth of the total number of strikers). This, as has already been pointed out, was the largest number of Negroes ever involved in any organized action under the leadership of the Party and revolutionary trade unions. These Negro miners and their families displayed the greatest militancy, actively in leading capacity in all phases of strike and union activity, on the picket lines, on strike and relief committees, as officers in the union and women’s auxiliaries, etc. Negro miners constituted the backbone of the strike in a number of mines.

Our principle of working-class solidarity met with enthusiastic response on the part of the large masses of white miners. This is shown by the fact that even in locals with one or two Negro miners, these were almost invariably placed in leading positions on Strike Committees and as officers of the local unions. On the whole, the splitting tactics of the coal operators received a smashing defeat in the strike.

In developing and cementing this unity, the National Miners Union played a leading role. The fact that the strike was led by our revolutionary union, which placed in the forefront of its program, unity of white and Negro miners on the basis of a struggle for the demands of the latter, was without doubt the greatest factor contributing to this working-class solidarity. From the outset the basic demand of the Negro miners, “Equal rights including wages, etc., no discrimination in work assignments,” was placed forward as a main strike demand, and a constant agitation for solidarity was carried out by the union among the masses of miners.

It would be incorrect, however, to fail to recognize that this unity was to a considerable extent spontaneous; that the objective conditions in the coal fields were particularly favorable for the development of working class solidarity among the miners. The increasing starvation and slavery among miners prior to the strike has brought masses of them, both Negro and white, to regard unity in the struggle against the operators as an economic necessity. Hence their broad acceptance of our program in this respect.

The chief shortcoming of our Party and Union however, consists in the fact that we allowed the question of unity of Negro and white workers to remain too long at the elementary stage of unity in the struggle for equal rights on the job, unity as an economic necessity. In other words, we did not sufficiently politicalize the strike in the direction of the struggle against Negro oppression. Concretely, Jim Crowism is rampant in many mining towns throughout the strike area. Not only are Negroes segregated in regards to residence in the company patches, and in mining towns, but they are also discriminated against in public places and institutions- restaurants, theatres, swimming pools, etc.

It is obvious that by involving the miners in actions for the smashing of Jim Crow laws and practices in the mining committees, our union could have succeeded in breaking through much of this Jim Crowism and in this manner would have found way to still broader strata of the Negro miners. Such actions could have taken the form of mass boycott of places discriminating against Negroes, the establishment of mass picketing before these places with placards containing slogans, the sending of delegations of Negro and white miners elected at protest mass meetings to local authorities demanding the cessation of these Jim Crow practices, etc., etc. The most opportune time for such actions was, when the mass movement was in full swing.

Moreover, the drawing of masses of white workers into active struggle against Jim Crowism (which is chauvinism in practice) is part and parcel of the struggle against chauvinistic tendencies among them. On the whole the organization of mass actions against local Jim-Crowism would have resulted in the raising of the whole movement to a higher political plane, and would have placed the unity of Negro and white workers on a more lasting basis. Our failure to organize such struggles resulted in the loss of a great opportunity by the Party and union for politicalization of the strike in regard to the Negro question. Therefore this failure must be regarded as a major political shortcoming of the strike as a whole.

The Scottsboro and Camp Hill affairs also provided excellent issues for the politicalization of the strike in regards to the struggle for Negro rights. Wherever the question was brought forth sharply, favorable results were registered by our Union, both organizationally and in increased influence. For example, a Negro miner is reported to have said that he supported our Union, not because it put forth the demand of equality for the Negro miners (pointing out that the strike-breaking U.M.W.A. also included in its constitution a clause on equality), “but because the N.M.U. fought for the release of the Scottsboro lads.” Our shortcoming in this regard lies in the fact that we did not systematically organize the participation of our union in this campaign. Our activities were mostly confined to adoption of resolutions and sending of tele- grams. True, special meetings were called by the I.L.D. but these meetings were badly organized and the participation of our Union was weak.

II.

Another grave shortcoming of the strike was our failure to concretize our demands for the Negro miners. While our union placed the general demands of the Negro miners in the strike program, no steps were taken to concretize these demands on the basis of their local grievances. Thus the question of segregation in the company patches, discrimination in living conditions within the patches, and types of work given to Negro miners, the denial of the right to occupy skilled and higher paid jobs, the question of relegating Negro to bad entries, the barring of them from certain so-called good mines, and numerous grievances which vary from mine to mine, were not concretely formulated during the strike. The question of concretization of demands is a question around which hinges the difference between reformist and revolutionary tactics. The Negro miner, referred to above, correctly pointed out that the U.M.W.A. fakers also placed in their constitution “no discrimination on account of race, creed or color,” which of course does not prevent them from carrying out the most vicious Jim Crow policy in regards to the Negro miners.

The strike offers valuable lessons in regard to the building up of the mass circulation of the Liberator. The paper was received enthusiastically by both Negro and white miners and used successfully in gaining wider contacts among the Negro miners for the strike and the union. However, this broader role of the Liberator was not at first fully appreciated as witnessed in our failure to organize its systematic distribution, and to make a beginning in the work of building up a mass circulation of the Liberator in the mining fields. A smashing blow, therefore, was given to the tendency to regard this paper as merely an organizer for the L.S.N.R. and failing to see its broader role as an organizer for Our mass organizations, union, unemployed councils, etc., among the Negro workers.

In connection with these main shortcomings a number of additional weaknesses must be registered, not one special leaflet was distributed among the Negro miners who remained at work, explaining to them why they should join the strike; no special discussion on the Negro question was organized in the local union during the course of the strike, etc., etc.

All of these shortcomings can be largely attributed to our failure to place the work among Negroes on an organized basis. Only at a relatively late stage in the strike, in fact when the strike wave was already on the ebb, did we set up a Negro Department in the Union and work out a concrete program for the development of this work.

This program, adopted by the Central Rank and File Strike Committee, has until now been but weakly put into operation.

At the present time, the union is faced with the tasks of overcoming its isolation and intrenching itself in the mines among the main masses of miners who have been driven back to work. Under these conditions, it is urgently necessary to carry into effect the following main tasks:

1. The concretization of the demands of the Negro miners on the basis of the local conditions in each mine. To conduct a real struggle against any attempts of the coal operators to victimize Negro miners for strike activities by placing our demands of “no discrimination of militant Negro miners” as a condition in local strike settlements.

2. The organization of mass actions for the smashing of Jim Crow laws and customs in mining committees. (The Pittsburgh Party district proposes to organize broad united front anti-Jim-Crow conferences on a section basis, picking out in this respect two sections where Jim Crowism is most rampant. These to be called under the joint auspices of the NMU, MWIL and LSNR, will have the task of organizing a real campaign against local Jim-Crowism.)

3. Organization of a sharp struggle against all hangovers of boss class prejudices in our ranks.

4. The organization of the more active participation of our union in the Scottsboro and Camp Hill campaign through the utilization of this campaign to widen contacts among Negro miners, in building up of the union and in development of Negro departments and committees in the Union.

5. Organization of discussions in the local unions in connection with carrying out tasks in Negro work.

6. Building up of mass circulation of the Liberator in the mining fields, through the utilization of the paper as an organizer for the union among Negro miners.

7. Organization of Committees for Work among Negro Miners in each local union, for the purpose of initiating this work.

The party through its fraction in the mining fields, must be the main driving force in carrying out the above tasks.

It is of the utmost importance that these lessons of the Miners’ Strike be energetically and conscientiously applied in the development of our Negro work in the steel campaign, in which industry Negroes constitute a basic section of the workers.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.

PDF of full issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1931/v08-n240-NY-oct-06-1931-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of full issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1931/v08-n241-NY-oct-07-1931-DW-LOC.pdf