Filip Filipović, veteran Socialist, the first Secretary of the Yugoslav Communist Party, Chair of the Balkan Communist Federation, and elected mayor of Belgrade with a valuable overview of the political situation in the mid-1920s.

‘Situation in Yugo-Slavia’ by Boshkovitch (Filip Filipović) from Communist International. Vol. 2 No. 8. February 1, 1925.

I.

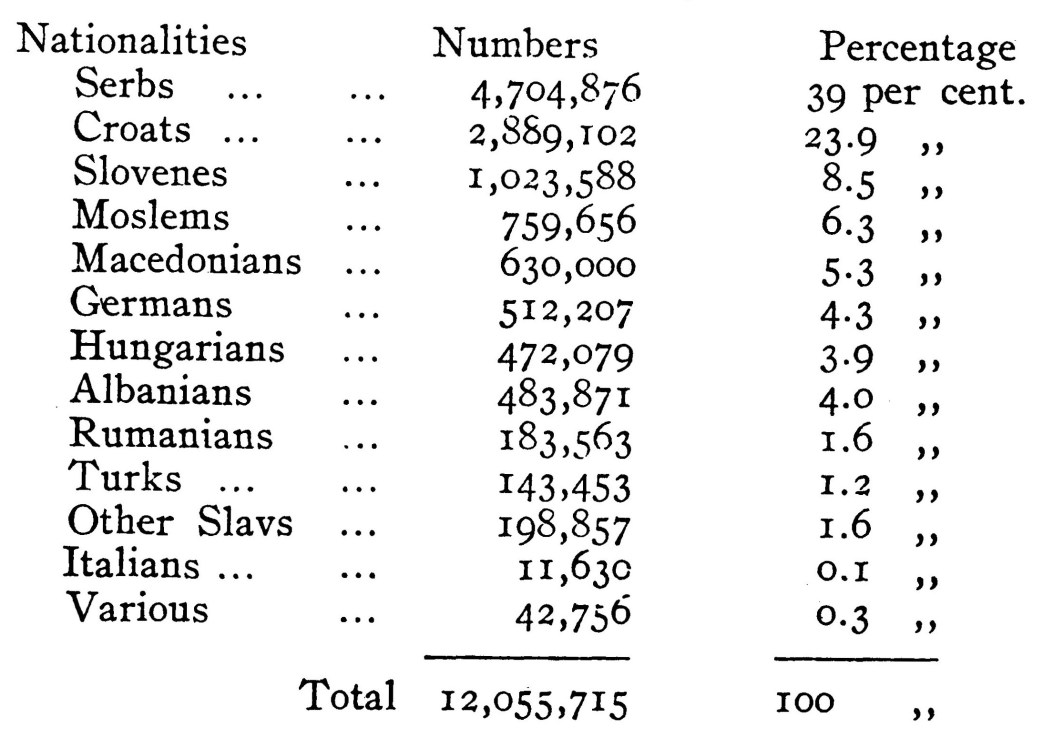

YUGO-SLAVIA is one of the small States which were created by the Entente as a result of the Versailles Treaty and of the subsequent treaties. Yugo-Slavia has been formed out of parts of six States (Serbia, Austria, Hungary, Turkey, Montenegro and Bulgaria), and is based on the annexation of various territories populated by different nationalities. The following statistics show the nature of the Yugo-Slavian population according to the census of 1921:

Already from the first when the Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian Kingdom (Yugo-Slavia) was established, the Croatian and Slovenian bourgeoisie betrayed the national liberation movement and refused to support the revolutionary movement of the peasantry which was fighting for land and freedom. They invited the Serbian and French army “for the re-establishment of law and order.” They capitulated of their own accord before the Serbian bourgeoisie thereby revealing their counter-revolutionary nature.

While the revolutionary movement was at its height, the Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian bourgeoisie worked harmoniously together. By combined effort they defeated the strike movement of the workers, peasant revolts and the movement of the oppressed nationalities for self-determination. It was only when the revolutionary wave was abating that the Serbian bourgeoisie and the Croatian-Slovenian bourgeoisie came to loggerheads The period of the joint rule of the entire Yugo-Slavian bourgeoisie, which received the energetic assistance of social democracy, lasted from 1918 to the end of 1920. The hegemony of the Serbian bourgeoisie began at the end of 1920 and lasted till July 27th, 1924. Serbian imperialists deny the existence of a national question in Yugo-Slavia during the 1921-24 period, on the plea that Serbs, Slovenes, and Macedonians were supposed to represent one nation. The representatives. of the Serbian bourgeoisie produced the “Vidovdansk” constitution, which establishes Serbian hegemony in Yugo-Slavia. White terror began to spread, fascist organisations were formed, and innumerable political trials took place. Among the hardest hit were of course, the Communist Party and the Red Trade Unions; for the “Defence of the Realm Act” was mainly directed against Communists.

The fascist regime of the Serbian bourgeoisie, which was intended to destroy the revolutionary movement, produced contrary results by making the national crisis in Yugo-Slavia more acute and by driving workers and peasants into a close union. On July 12th, 1924, the Paschitch Government delivered its last attack against the vanguard of the working class. It issued a decree prohibiting the Independent Labour Party, the Red Trade Unions and the Young Communist Leagues, and also arrested goo Communists. When this attack failed to produce the desired results, the Serbian bourgeoisie abandoned “the policy of frontal attacks for the policy of compromise,” from Pashitch and Pribitchevitch down to Davidovitch, Koroshtzu and Spakho.

II.

The fight for national liberation of the nationalities oppressed by the Serbs is identical with the fight of the peasantry for more land and against foreign landowners and capitalists since the peasant element predominates among these nationalities.

In Macedonia, 85 per cent. of the total population are peasants, two-thirds of whom belong to the poor peasantry. It is precisely the poor peasantry which suffers most from the national yoke, as the landless and poor peasants are Macedonians. A considerable part of the land is in the hands of Turkish and Serbian landowners (Aghas and Beks). The agrarian reform of 1919 promised the abolition of the feudal system in Macedonia, as well as in other regions. But in reality, this decree only remained on paper, as the Macedonian feudal laws succeeded in reducing this reform to nought.

In Dalmatia, there are also relics of feudal relations. The land which the peasantry confiscated in 1918-19, was again taken away from it, and the peasantry had to pay arrears to the landowners just as before. The Serbian bourgeoisie knew how to protect the interests of Italian landowners in Dalmatia.

Moslem Bosnian feudal lords also came to an agreement with the Serbian bourgeoisie. They compelled the State to compensate them for their losses on the land, which had always been tilled by the Serbian semi-serf peasantry, they procured for themselves the right of purchase for the remaining land, thereby being guaranteed against any possibility of confiscation of the land belonging to them. Although the feudal system was officially abolished in Bosnia, the actual solution of the agrarian question was postponed.

In Croatia, Slovenia and Voyevodnia, capitalist relations had taken deep root in agriculture already previous to the world war, and had been the source of very acute class dissensions. When the military collapse took place in Austro-Hungary in 1918, the poor peasantry began the agrarian revolution which in 191g compelled the ruling classes to adopt the expedient of land reform.

As a result of the agrarian reform, landowners retained a considerable part of their landed property. Moreover, they were well-compensated for the confiscated land. The whole system of land purchase is only another form of the manner in which peasant produce is expropriated. By agrarian reform, the fascist regime of the Serbian bourgeoisie helped landowners to retain their big estates and to secure to themselves land rent.

In Macedonia and Voyevodnia, the Yugo-Slavian Government adopted a colonising policy and gave the land to Serbian volunteers. In Voyevodnia part of the land was confiscated from the big landowners for distribution among the soldiers belonging to the Serbian army. About 28,503 Serbian families settled as colonists and thereby 60,000 agricultural labourers were thrown out of work, as part of the big estates which employed them was divided among the colonists. These agricultural labourers are in an intolerable position, especially as there are no facilities for emigration to America or migration to the big estates in Hungary and where they might earn a living as they used to formerly. This colonisation policy has, of course, made the national differences in these regions even more acute than hitherto.

At present it is admitted even in government circles that ‘the agrarian question in Yugo-Slavia has not been solved, and the present government is preparing to introduce a new land reform bill.

Peasants are beginning to understand that they have been cheated by the bourgeois parties, that the fight for land is not yet over, and they cannot obtain land nor free themselves from the landowners’ yoke unless they unite with the workers to establish a workers’ and peasants’ government. On the other hand, the proletariat of peasant Yugo-Slavia has also come to the conclusion that it cannot be victorious without the support of the peasant masses. The Yugo-Slavian Communist Party has drawn up an agrarian programme, the main feature of which is the demand for the confiscation of all landowners, church, and big capitalist estates for distribution among the landless and poor peasantry.

Ill.

When the Serbian bourgeoisie began to attack the non-Serbian nationalities, it was confronted by the resistance of the working class and its vanguard the Yugo-Slavian Communist Party, which initiated a relentless fight against the hegemony of the Serbian bourgeoisie. With the help of the anti-Communist decree (Obzhana), and of the Defence of the Realm Act, the bourgeoisie began an offensive against the working class and succeeded in isolating it from the peasant movement and from the national revolutionary movement of the oppressed nationalities. The unsuccessful manoeuvring in respect of the national question and the fact that the proletariat failed to bring about a union with the peasant masses was very costly for the proletariat. At the end of 1920 and the beginning of 1921, the Serbian bourgeoisie deprived the working class of almost all achievements on the field of trade union and labour legislation. In many enterprises the eight-hour day was abolished, wages were reduced, labour protection and workers’ insurance were closed down, the Communist Party was driven underground, all working class organs were prohibited and a very large number of Party workers arrested.

After this onslaught, workers found it very difficult to reestablish their trade unions, to form an independent labour party and to conduct a defensive campaign against the ferocious attacks of the capitalists.

The legal as well as the material position of the working class went from bad to worse. The official report of the inspection of labour for 1923 acknowledges that capitalists grossly abuse the Defence of the Realm Act. They declared every strike to be a rising and demanded police intervention for its suppression.

The same official report states that the maximum wage of skilled workers is 200 dinars (80 dinars—about 1 dollar) a day, and that of unskilled workers—60 dinars. The lowest wage for skilled workers is—30 dinars, and for unskilled workers—15 dinars. Moreover, it must be borne in mind that a working class family consisting of father, mother and two children must have a minimum of 93.40 dinars a day to satisfy its most elementary needs. Naturally, the number of workers receiving 200 dinars a day is very small. According to trade union data, the average wage of metal workers is 50 dinars, and that of women compositors—35 to 45 dinars. Printers’ maximum wage is—93.10 dinars, but very few receive this wage.

The continuous economic crisis has also a detrimental effect on the working class. According to data of the Central Trade Union organ of the Red Labour Unions, there are about 250,000 unemployed. Bourgeois papers give the number of unemployed as 150,000.

The Pashitch and Pribichevitch government made their most ferocious attack on the working class when the Yugo-Slavian Communist Party and the Independent Labour Party introduced into their programme the foundation of the Leninist national policy—the slogan of national self-determination, including separation, namely establishment of independent Croatian, Slovenian and Macedonian Republics, as well as the slogan of a Balkan Federation of independent workers’ and peasants republics with equal rights. When the proletariat began to put into practice the united front with the peasantry, having issued the slogan of the workers’ and peasants’ government, it had to bear for the second time the brunt of the ferocious fascist attack described in the first chapter.

IV.

The black hundred Pashitch-Pribichevitch government was replaced on July 27th, 1924, by the government of the “left” bloc—the Davidovitch government. This government was composed of representatives of the Serbian bourgeoisie of a democratic persuasion (Davidovitch’s party), of Slovenian clerical—representatives of the Slovenian bourgeoisie (Dr. Koroshetz), of Bosnian Moslems—representatives of the big bourgeoisie (Dr. Spakho), and of one “independent” radical. This new government has also the support of the monarchist landowners’ federation, which represents the interests of the middle peasantry.

As to the Croatian Republican peasant party (Raditch’s party), its policy has a dual character. According to information received, this Party does not form part of the government, but its chairman, Raditch, has promised the government parliamentary support. This duality of the Raditch party finds is explanation in the fact that it has in its ranks almost the entire Croatian peasantry, including an overwhelming majority of poor peasants, as well as middle peasants and kulaks. What unites these various peasant sections is their common hatred of the hegemony of the Serbian bourgeoisie. If Raditch decided to form part of the Davidovitch government, or to give it adequate support, this would accelerate the process of differentiation within his party.

What then is the explanation of the fact that in the avowedly black hundred Yugo-Slavia reaction has been replaced by a so-called “democratic” era?

This change will be easily understood if one takes into consideration that the substance of this democratic-pacifist era is the Serbian bourgeoisie’s desire to get out of the difficult and intolerable position in which it has landed itself as a result of its fascist policy. Owing to the economic crisis and to the sanguinary regime of national and class oppression practised by Pashitch and Pribichevitch, the idea of a workers’ and peasants’ union has made great strides forward. This is best proved by the entry of the Croatian Republican peasant party (Raditch’s party) into the Peasant International, and by the tendency of the left elements of the other oppressed nationalities towards union between workers and peasants.

The new government really means that on the basis of the Vidovdansk constitution, which represents bourgeois interests only, the Serbian bourgeoisie is endeavouring to arrive at a compromise with the representatives of the Croatian and Slovenian bourgeoisie in order to extend its political and social basis. Consequently, Davidovitch will endeavour to appease the hegemony of the Serbian fascist bourgeoisie, to unite the capitalists and landowners of the oppressed nationalities and to isolate the peasant movement of these nationalities. It therefore stands to reason that this “left” bloc is meant to be a weapon in the hands of the Yugo-Slavian bourgeoisie enabling it to dominate over the workers and peasants. Withal, Davidovitch will make small concessions to the bourgeoisie of the oppressed nations for the purpose of smoothing away national differences. He will deceive the masses with high-sounding phrases about peace among nations, parliamentarism, “the sovereign” rights of nations, etc., etc. As a matter of course, the “left” bloc needs pacifism only as a screen for its efforts to frustrate union between workers and peasants.

The Yugo-Slavian Communist Party will have to do its utmost to expose the counter-revolutionary nature of the pacifist democratic regime of Davidovitch and Co. As the Davidovitch government is supported by the national parties, it stands to reason that special attention must be paid to the national question. At present the petty bourgeois parties of Bosnia, Croatia and Solvenia are half-hearted even on this question. The Croatian, Solvenian and Bosnian bourgeoisie does not even keep a minimum of its promises, thereby betraying the national liberation movement in the struggle with the hegemony of the Serbian bourgeoisie. By taking up a definite and clear position with regard to these questions, the Yugo-Slavian Communist Party will be able to expose the vacillations of the petty bourgeoisie, and to submit to severe criticism the right digression in connection with this question, which is making itself felt also in the upper strata of Serbian trade unions. The Yugo-Slavian Communist Party will also carry on an energetic struggle against the reactionary foreign policy of the Davidovitch government, which is nothing but a perpetuation of the Pashitch policy. It will demand the resumption of political and economic relations between Yugo-Slavia and the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics.

The Davidovitch Government, itself by its reactionary policy towards the working class, is helping the Yugo-Slavian Communist Party to expose the Yugo-Slavian imperialists who are parading as pacifists. The new government’s permission to Red Labour Unions to resume their activities is mere talk. The attitude towards the Independent Labour Party is exactly the same as under the Pashitch regime; there are still several hundred comrades in prison.

There is no doubt whatever that in Yugo-Slavia too, events will help the Communists. The task before the Communists will be to expose relentlessly every action of the “left bloc” and will endeavour to establish and strengthen the union between workers and peasants, whose final goal is—the workers’ and peasants’ government.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n08-feb-1925-new-series-CI-grn-riaz.pdf