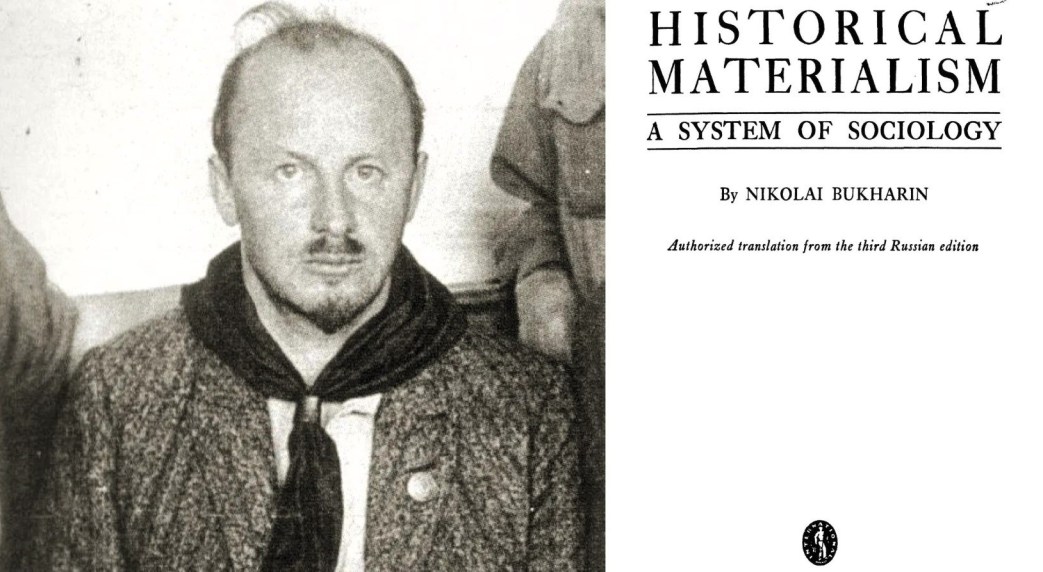

From Bukharin’s widely read and taught 1921 work on historical materialism, with several editions printed in the 1920s until his 1929 fall.

‘The Use of Contradictions in the Historical Process’ (1921) by Nikolai Bukharin from Historical Materialism: A System of Sociology. International Publishers, New York. 1925.

The basis of all things is therefore the law of change, the law of constant motion. Two philosophers particularly (the ancient Heraclitus and the modern Hegel, as we have already seen) formulated this law of change, but they did not stop there. They also set up the question of the manner in which the process operates. The answer they discovered was that changes are produced by constant internal contradictions, internal struggle. Thus, Heraclitus declared: “Conflict is the mother of all happenings,” while Hegel said: “Contradiction is the power that moves things.”

There is no doubt of the correctness of this law. A moment’s thought will convince the reader. For, if there were no conflict, no clash of forces, the world would be in a condition of unchanging, stable equilibrium, i.e., complete and absolute permanence, a state of rest precluding all motion. Such a state of rest would be conceivable only in a system whose component parts and forces would be so related as not to permit of the introduction of any conflicts, as to preclude all mutual interaction, all disturbances. As we already know that all things change, all things are “in flux”, it is certain that such an absolute state of rest cannot possibly exist. We must therefore reject a condition in which there is no “contradiction between opposing and colliding forces”, no disturbance of equilibrium, but only an absolute immutability. Let us take up this matter somewhat more in detail.

In biology, when we speak of adaptation, we mean that process by which one thing assumes a relation toward another thing that enables the two to exist simultaneously. An animal that is “adapted” to its environment is an animal that has achieved the means of living in that environment. It is suited to its surroundings, its qualities are such as to enable it to continue to live. The mole is “adapted” to conditions prevailing under the earth’s surface; the fish, to conditions in the water; either animal transferred to the other’s environment will perish at once.

A similar phenomenon may be observed also in so called “inanimate” nature: the earth does not fall into the sun, but revolves around it “without mishap”. The relation between the solar system: and the universe which surrounds it, enabling both to exist side by side, is a similar relation. In the latter case we commonly speak, not of the adaptation, but of the equilibrium between bodies, or systems of such bodies, etc. We may observe the same state of things in society. Whether we like it or not, society lives within nature: is therefore in one way or another in equilibrium with nature. And the various parts of society, if the latter is capable of surviving, are so adapted to each other as to enable them to exist side by side: capitalism, which included both capitalists and workers, had a very long existence!

In all these examples it is clear that we are dealing with one phenomenon, that of equilibrium. This being the case, where do the contradictions come in? For there is no doubt that conflict is a disturbance of equilibrium. It must be recalled that such equilibrium as we observe in nature and in society is not an absolute, unchanging equilibrium, but an equilibrium in flux, which means that the equilibrium may be established and destroyed, may be reestablished on a new basis, and again disturbed.

The precise conception of equilibrium is about as follows: “We say of a system that it is in a state of equilibrium when the system cannot of itself, i.e., without supplying energy to it from without, emerge from this state.” If – let us say – forces are at work on a body, neutralizing each other, that body is in a state of equilibrium; an increase or decrease in one of these forces will disturb the equilibrium.

If the disturbance of equilibrium is of short duration and the body returns to its former position, the equilibrium is termed stable; if this does not ensue, the equilibrium is unstable. In the natural sciences we have mechanical equilibrium, chemical equilibrium, biological equilibrium. (Cf. H. von Halban: Chemisches Gleichgewicht, in Handwörterbuch der Naturwissenschaften, vol. ii, Jena, 1912, pp.470-519, from which we take the above quotation.)

In other words, the world consists of forces, acting in many ways, opposing each other. These forces are balanced for a moment in exceptional cases only. We then have a state of “rest”, i.e., their actual “conflict” is concealed. But if we change only one of these forces, immediately the “internal contradictions” will be revealed, equilibrium will be disturbed, and if a new equilibrium is again established, it will be on a new basis, i.e., with a new combination of forces, etc. It follows that the “conflict”, the “contradiction”, i.e., the antagonism of forces acting in various directions, determines the motion of the system.

On the other hand, we have here also the form of this process: in the first place, the condition of equilibrium; in the second place, a disturbance of this, equilibrium; in the third place, the reestablishment of equilibrium on a new basis. And then the story begins all over again: the new equilibrium is the point of departure for a new disturbance, which in turn is followed by another state of equilibrium, etc., ad infinitum. Taken all together, we are dealing with a process of motion based on the development of internal contradictions.

Hegel observed this characteristic of motion and expressed it in the following manner: he called the original condition of equilibrium the thesis, the disturbance of equilibrium the antithesis, the reestablishment of equilibrium on a new basis the synthesis (the unifying proposition reconciling the contradictions). The characteristic of motion present in all things, expressing itself in this tripartite formula (or triad) he called dialectic.

The word “dialectics” among the ancient Greeks meant the art of eloquence, of disputation. The course of a discussion is as follows: one man says one thing, another the opposite (“negates” what the first man said); finally, “truth is born from the struggle”, and includes a part of the first man’s statement and a part of the second man’s (synthesis). Similarly, in the process of thought. Since Hegel, being an idealist, regards everything as a self-evolution of the spirit, he of course did not have any disturbances of equilibrium in mind, and the properties of thought as a spiritual and original thing were therefore, in his mind, properties also of being. Marx wrote in this connection: “My dialectic method is not only different from the Hegelian, but is its direct opposite. To Hegel, the life-process of the human brain, i.e., the process of thinking, which, under the name of `the Idea’, he even transforms into an independent subject, is the demiurgos of the real world, and the real world is only the external phenomenal form of `the Idea’. With me, on the contrary, the ideal is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought . . . . With him (Hegel) it (dialectics) is standing on its head. It must be turned right side up again, if you would discover the rational kernel within the mystical shell” (Capital, Chicago, 1915, vol. i, p.25). For Marx, dialectics means evolution by means of contradictions, particularly, a law of “being”, a law of the movement of matter, a law of motion in nature and society. It finds its expression in the process of thought. It is necessary to use the dialectic method, the dialectic mode of thought, because the dialectics of nature may thus be grasped.

It is quite possible to transcribe the “mystical” (as Marx put it) language of the Hegelian dialectics into the language of modern mechanics. Not so long ago, almost all Marxians objected to the mechanical terminology, owing to the persistence of the ancient conception of the atom as a detached isolated particle. But now that we have the Electron Theory, which represents atoms as complete solar systems, we have no reason to shun this mechanical terminology. The most advanced tendencies of scientific thought in all fields accept this point of view. Marx already gives hints of such a formulation (the doctrine of equilibrium between the various branches of production, the theory of labor value based thereon, etc.).

Any object, a stone, a living thing, a human society, etc., may be considered as a whole consisting of parts (elements) related with each other; in other words, this whole may be regarded as a system. And no such system exists in empty space; it is surrounded by other natural objects, which, with reference to it, may be called the environment. For the tree in the forest, the environment means all the other trees, the brook, the earth, the ferns, the grass, the bushes, together with all their properties. Man’s environment is society, in the midst of which he lives; the environment of human society is external nature. There is a constant relation between environment and system, and the latter, in turn, acts upon the environment. We must first of all investigate the fundamental question as to the nature of the relations between the environment and the system; how are they to be defined; what are their forms; what is their significance for their system. Three chief types of such relations may be distinguished.

1. Stable equilibrium. This is present when the mutual action of the environment and the system results in an unaltered condition, or in a disturbance of the first condition which is again reestablished in the original state. For example, let us consider a certain type of animals living in the steppes. The environment remains unchanged. The quantity of food available for this type of beast neither increases nor decreases; the number of animals preying upon them also remains the same; all the diseases, all the microbes (for all must be included in the “environment”), continue to exist in the original proportions. What will be the result? Viewed as a whole, the number of our animals will remain the same; some of them will die or be destroyed by beasts of prey, others will be born, but the given type and the given conditions of the environment will remain the same as they were before. This means a condition of rest due to an unchanged relation between the system (the given type of animals) and the environment, which is equivalent to stable equilibrium. Stable equilibrium is not always a complete absence of motion; there may be motion, but the resulting disturbance is followed by a reestablishment of equilibrium on the former basis. The contradiction between the environment and the system is constantly being reproduced in the same quantitative relation.

We shall find the case the same in a society of the stagnant type (we shall go into this question more in detail later). If the relation between society and nature remains the same; i.e., if society extracts from nature, by the process of production, precisely as much energy as it consumes, the contradiction between society and nature will again be reproduced in the former shape; the society will mark time, and there results a state of stable equilibrium.

2. Unstable equilibrium with positive (favorable) indication (an expanding system). In actual fact, however, stable equilibrium does not exist. It constitutes merely an imaginary, sometimes termed the “ideal”, case. As a matter of fact, the relation between environment and the system is never reproduced in precisely the same proportions; the disturbance of equilibrium never actually leads to its reestablishment on exactly the same basis as before, but a new equilibrium is created on a new basis. For example, in the case of the animals mentioned above, let us assume that the number of beasts of prey opposing them decreases for some reason, while the available food increases. There is no doubt that the number of our animals would then also increase; our “system” will then grow; a new equilibrium is established on a better basis; this means growth. In other words, the contradiction between the environment and the system has become quantitatively different.

If we consider human society, instead of these animals, and assume that the relation between it and nature is altered in such manner that society – by means of production – extracts more energy from nature than is consumed by society (either the soil becomes more fruitful, or new tools are devised, or both), this society will grow and not merely mark time. The new equilibrium will in each case be actually new. The contradiction between society and nature will in each case be reproduced on a new and “higher” basis, a basis on which society will increase and develop. This is a case of unstable equilibrium with positive indication.

3. Unstable equilibrium with negative indication (a declining system). Now let us consider the quite different case of a new equilibrium being established on a “lower” basis. Let us suppose, for example, that the quantity of food available to our beasts has decreased, or that the number of beasts of prey has for some reason increased. Our animals will die out. The equilibrium between the system and the environment will in each case be established on the basis of the extinction of a portion of this system. The contradiction will be reestablished on a new basis, with a negative indication. Or, in the case of society, let us assume that the relation between it and nature has been altered in such manner that society is obliged to consume more and more and obtain less and less (the soil is exhausted, technical methods become poorer, etc.). New equilibrium will here be established in each case on a lowered basis, by reason of the destruction of a portion of society. We are now dealing with a declining society, a disappearing system, in other words, with motion having a negative indication.

Every conceivable case will fall under one of these three heads. At the basis of the motion, as we have seen, there is in fact the contradiction between the environment and the system, which is constantly being reestablished.

But the matter has another phase also. Thus far we have spoken only of the contradictions between the environment and the system, i.e., the external contradictions. But there are also internal contradictions, those that are within the system. Each system consists of its component parts (elements), united with each other in one way or another. Human society consists of people; the forests, of trees and bushes; the pile of stones, of the various stones; the herd of animals, of the individual animals, etc. Between them there are a number of contradictions, differences, imperfect adaptations, etc. In other words, here also there is no absolute equilibrium. If there can be, strictly speaking, no absolute equilibrium between the environment and the system, there can also be no such equilibrium between the elements of the system itself.

This may be seen best by the example of the most complicated system, namely, human society. Here we encounter an endless number of contradictions; we find the struggle between classes, which is the sharpest expression of “social contradictions”, and we know that “the struggle between classes is the motive force of history”. The contradictions between the classes, between groups, between ideals, between the quantity of labor performed by individuals and the quantity of goods distributed to them, the planlessness in production (the capitalist “anarchy” in production), all these constitute an endless chain of contradictions, all of which are within the system and grow out of its contradictory structure (“structural contradictions”). But these contradictions do not of themselves destroy society. They may destroy it (if, for example, both opposing classes in a civil war destroy each other), but it is also possible they may at times not destroy it.

In the latter case, there will be an unstable equilibrium between the various elements of society. We shall later discuss the nature of this equilibrium; for the present we need not go into it. But we must not regard society stupidly, as do so many bourgeois scholars, who overlook its internal contradictions. On the contrary, a scientific consideration of society requires that we consider it from the point of view of the contradictions present within it. Historical “growth” is the development of contradictions.

We must again point out a fact with which we shall have to deal more than once in this book. We have said that these contradictions are of two kinds: between the environment and this system, and between the elements of the system and the system itself. Is there any relation between these two phenomena? A moment’s thought will show us that such a relation exists.

It is quite clear that the internal structure of the system (its internal equilibrium) must change together with the relation existing between the system and its environment. The latter relation is the decisive factor; for the entire situation of the system, the fundamental forms of its motion (decline, prosperity, or stagnation) are determined by this relation only.

Let us consider the question in the following form: we have seen above that the character of the equilibrium between society and nature determines the fundamental course of the motion of society. Under these circumstances, could the internal structure continue for long to develop in the opposite direction? Of course not. In the case of a growing society, it would not be possible for the internal structure of society to continue constantly to grow worse. If, in a condition of growth, the structure of society should become poorer, i.e., its internal disorders grow worse, this would be equivalent to the appearance of a new contradiction: a contradiction between the external and the internal equilibrium, which would require the society, if it is to continue growing, to undertake a reconstruction, i.e., its internal structure must adapt itself to the character of the external equilibrium. Consequently, the internal (structural) equilibrium is a quantity which depends on the external equilibrium (is a “function” of this external equilibrium).

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/dli.ministry.13983/E00417_Historical%2520Matrialism_text.pdf