The REVIEW wanted to be sure you knew where your cup of tea came from.

‘A Cup of Tea’ by Rhyne Khhyve from International Socialist Review. Vol. 14 No. 5. November, 1913.

THE leaves of the tea bush were first named TEA by the Chinese. Few of us realize the arduous toil that has been spent in raising, preparing and shipping the tea we drink. The leaves of tea from which the beverage is brewed have probably passed through forty or fifty hands before they reach your kitchen. And the story of tea, from the gardens to the table, is one that would interest everybody.

When tea was first shipped to England many years ago, transportation was so uncertain and so costly, and the leaf itself so scarce, that only the very rich, who were accustomed to entertain princes and grandees, could afford to pay fifty dollars for a pound of tea.

Green and black tea are produced from the leaves of the same plant by varying processes of manufacture. For many years China was the home of the tea industry, but the modern developments of production and consumption have rendered the subject of Chinese tea one of lesser importance. The conservative tendencies of the Chinese people have prevented them from adopting the modern methods of extensive cultivation based on scientific principles and the manipulation of crops by machinery in place of hand labor. Consequently, for many years their export trade has been a diminishing one.

In 1908 the tea exports from China amounted to only 188,000,000 pounds against 240,000,000 pounds shipped out of India. China sold 80,000,000 pounds of brick and tablet tea to Asiatic and European Russia. The method of compressing tea into tablets or bricks is unknown in America and Western Europe. It doubtless arose from the necessity of reducing bulk to a minimum for conveyance by caravan across the great trade routes of Asia, and now that the railroads and steamships have supplemented more primitive methods of transit, the system is still continued to meet the wants of the consumer who will not recognize tea in any other shape.

The Russians have themselves established several important factories at Hankow, China. There they use tons and tons of tea dust and broken bits of tea which are compressed to such a condition of hardness that they resemble wood or stone and are passed around instead of currency in certain Russian districts.

The brick tea prepared by the Chinese is somewhat different. It is made for the overland trade with Thibet. This tea is mostly prepared from exceedingly rough leaf, including even bush prunings. It is panned, rolled, fermented and divided into various classes or qualities. It is then steamed and placed in a molding frame of wood to compress it into the size and shape of brick wanted. For transit they are packed twelve together in hides, sewed up while moist, which contract to make a strong, tight package sixty or seventy pounds in weight. These bales are carried on the backs of coolies for great distances across very high passes into Thibet. The trade is estimated at 19,000,000 pounds per annum.

After two years’ growth, the tea bushes are usually from two to six feet in height. They are repeatedly cut to cause the plants to spread out into many branches.

In the early days tea growers in India and Ceylon attempted the Chinese method, but now almost everything, from the plucking stage onward, is done by machinery. Everywhere women and children pluck the leaves and twice daily they are taken to the factory. In many places all over the tea-raising world, only during the plucking is tea touched by human hands.

The leaves are spread out on thin bamboo or wire racks, under cover, and allowed to wither for from eighteen to thirty hours, after which they are in a soft, flaccid condition, ready for rolling. The object of rolling is to crush the leaves and break their cells so as to liberate the juices. Next the leaves are rolled out in layers one or two inches thick and allowed to ferment.

A further rolling process closes the tea leaves and they are later subjected to a first firing, the ovens being sometimes 240 degrees, Fahrenheit. They are then crisp and firm.

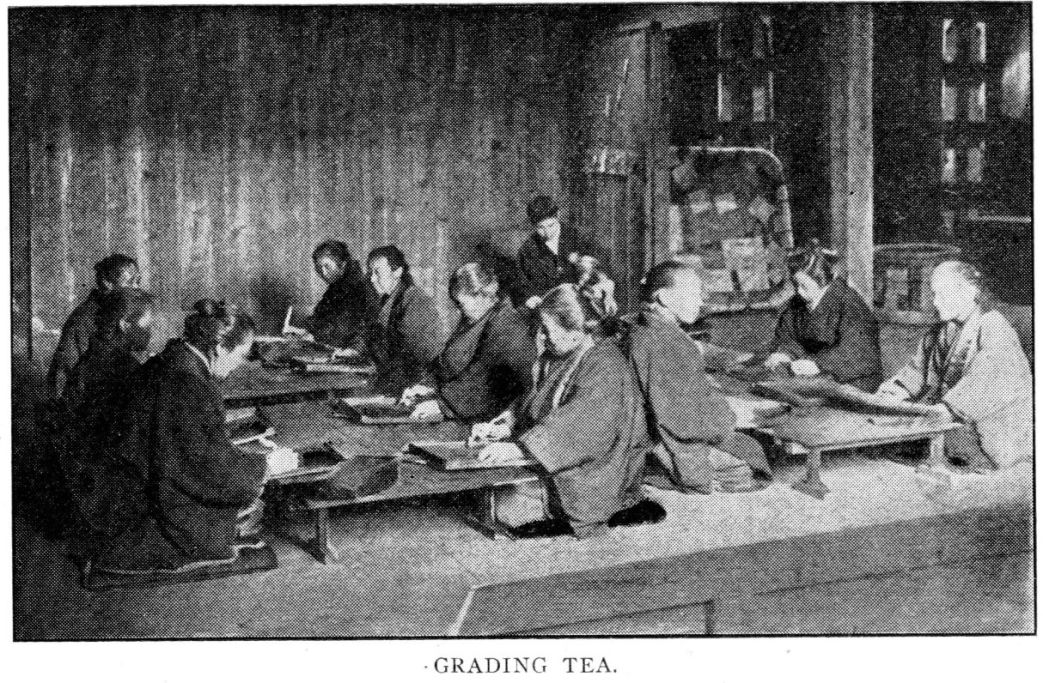

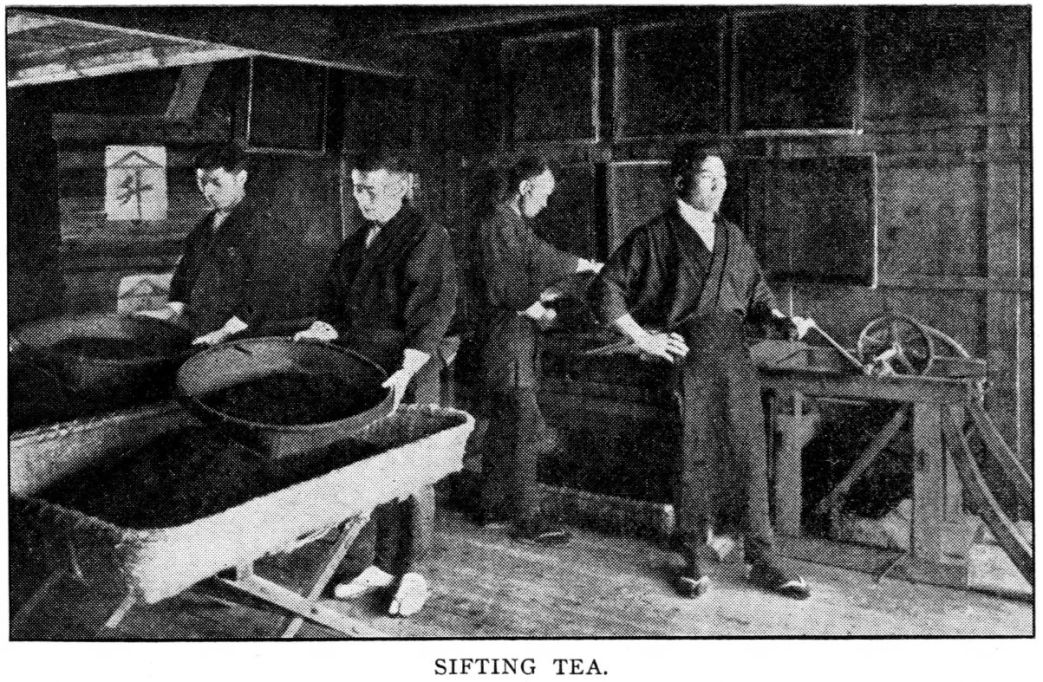

Up to this point of manufacture, the leaf has been in the stalk, the leaves and bud being unseparated. They are now broken apart and sorted by hand or mechanical sifters into the various grades and qualities. Upon completion of sifting and sorting, the tea is again fired and is packed tightly, while warm, in lead-lined chests and the lead covers completely soldered over it so that it may be kept absolutely air-tight until required for use.

All Oolong tea is raised on the Island of Formosa. English capitalists have sought to raise Oolong in the British provinces because of its delicate flavor and exquisite bouquet, but without success.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v14n05-nov-1913-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf