Ralph Winston Fox was a British Communist, journalist, historian, and Marxist literary critic. Here he looks at the social setting and impact of the two French novelists as well as how they were viewed by Marx and Engels. This article was published posthumously, shortly after Fox was killed in Spain at age 36 while fighting with the International Brigades at the Battle of Lopera with fellow British Communist, the poet John Cornford on December 27, 1936.

‘Balzac and Flaubert: The Prometheans of the Novel’ by Ralph W. Fox from New Masses. Vol. 23 No. 7. May 11, 1937.

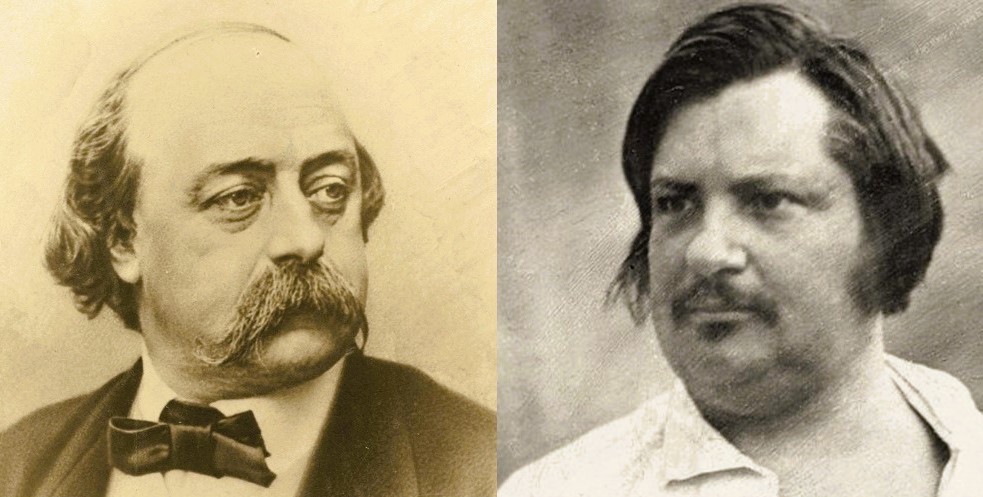

Balzac and Flaubert, the author says, dared heroic tasks to fulfill their conception of the artist’s role

MARX concluded one of his articles in the New York Tribune during 1854 with a reference to the Victorian realists: “The present brilliant school of novelists in England, whose graphic and eloquent descriptions have revealed more political and social truths to the world than have all the politicians, publicists, and moralists added together, has pictured all sections of the middle class, beginning with the ‘respectable’ rentier and owner of government stocks, who looks down on all kinds of ‘business’ as being vulgar, and finishing with the small shopkeeper and lawyer’s clerk. How have they been described by Dickens, Thackeray, Charlotte Brontë, and Mrs. Gaskell? As full of self-conceit, prudishness, petty tyranny, and ignorance. And the civilized world has confirmed their verdict in a damning epigram which it has pinned on that class, that it is servile to its social superiors and despotic to its inferiors.”

About the same time as these words appeared in the New York paper, Flaubert in physical agony was writing to his friend Louis Bouilhet: “Laxatives, purgatives, derivatives, leaches, fever, diarrhoea, three nights without any sleep, a gigantic annoyance at the bourgeois, etc., etc. That’s my week, dear sir.” English and French novelists were alike faced with the same problem, that of giving artistic form and expression to a society which they could not accept. In England they only succeeded in the end by a kind of compromise with reality, but the whole history of France made such a compromise impossible in that country. No country of the modern world had passed through such terrific struggles as France, with her great revolution followed by twenty years of wars in which French armies marched and counter-marched across the feudal states of Europe till the final catastrophe of 1814.

Napoleon was the last great world-conqueror, but he was also the first bourgeois emperor. France was only able to support that vast war machine because in those years she began to catch up on her rival, England, to develop her industries, to introduce power machinery on a large scale, to create a great new internal market from her liberated peasantry. When the process was completed, a generation after Napoleon’s fall, you had the strange paradox that a completely new France, a France in which money spoke the last word, a France of bankers, traders, and industrialists, was being ruled by the feudal aristocracy whom the revolution had apparently smashed into fragments. Yet the heroic tradition of this new France with its old rulers remained essentially revolutionary, on the one hand the Jacobin of ’93, on the other the soldier of Napoleon.

Balzac, the great genius of the century, consciously set himself the task of writing “the natural history” of this society, Balzac who was himself a monarchist, a legitimist, and a Catholic. His Comédie Humaine, that encyclopædic study of human life, was a revolutionary picture of his age; revolutionary not because of the intention of its author, but because of the truth with which the inner life of his time is described. Engels, in his letter to the English novelist, Margaret Harkness, has emphasized the truth of Balzac’s realist method:

“Balzac, whom I consider a far greater master of realism than all the Zolas, passés, présents et à venir, in his Comédie Humaine gives us a most wonderfully realistic history of French society, describing in chronicle fashion, almost year by year, from 18161 to 1848, the progressive inroads of the rising bourgeoisie upon the society of nobles that reconstituted itself after 1815, and that set up again as far as it could the standard of la vieille politesse française. He describes how the last remnants of this, to him, model society gradually succumbed before the intrusion of the vulgar, moneyed upstart, or were corrupted by him, how the grande dame, whose conjugal infidelities were but a mode of asserting herself, in perfect accordance with the way she had been disposed of in marriage, gave way to the bourgeoise who gains her husband for cash or customers; and around this central picture he groups a complete history of French society, from which, even in economic details, for instance, the rearrangement of real and personal property after the Revolution, I have learnt more than from all the professed historians, economists, and statisticians of the period together. Well, Balzac was politically a legitimist; his great work is a constant elegy unto the irreparable decay of good society; his sympathy is with the class that is doomed to extinction. But for all that, his satire is never more cutting, his irony more biting than when he sets in motion the very men and women with whom he sympathizes most deeply–the nobles. And the only men of whom he speaks with undisguised admiration are his bitterest political antagonists, the Republican heroes of the Cloître-Saint-Merri, the men who at that time (1830-36), were indeed the representatives of the popular masses. That Balzac was thus compelled to go against his own class sympathies and political prejudices, that he saw the necessity of the downfall of his favorite nobles and described them as people deserving no better fate; that he saw the real men of the future where, for the time being, they alone could be found–that I consider one of the greatest triumphs of Realism, one of the greatest features in old Balzac.”

BALZAC has himself explained in the preface to the Comédie that he saw man as the product of society, saw him in his natural environment, and that he felt the same desire to study him scientifically as the great naturalists feel who study the animal world. His political and religious views were those of the old feudal France, but this attitude to man, this conception of the human comedy, was the product of the Revolution, of the Jacobins who so ruthlessly smashed the social fetters on French society, of the marching soldiers who brought the monarchies of Europe to their knees before the leadership of Napoleon. Balzac, indeed, was France’s literary Napoleon, for he destroyed feudal ideas in literature as thoroughly as the great soldier destroyed the feudal system in politics. In Restoration France, criticism of capitalist society, of the new capitalist social relations, was concealed under the mediæval disguise of romanticism. The extravagances of the Romantics in their personal lives, quite as much as their extravagances in art, were a protest against the present as well as an escape from it. Balzac neither protested nor escaped. He had all the imagination, the poetry, and even the mysticism of the Romantics, but he rose above them and showed the way to a new literature by his realist attack on the present. He was able to conceive the reality of contemporary life imaginatively, to conceive it almost on the scale on which Rabelais and Cervantes had conceived it. It was his fortune, however, to have lived in the early part of the century when the force and fire of that immense outburst of national energy which made the Revolution and the Napoleonic epic was still able to make itself felt in the literary movement of the thirties and early forties.

It was a long way from Balzac to the Flaubert whose dominant passion was hatred and disgust for the bourgeoisie, who signed his letters “Bourgeoisophobus,” and suffered such physical and mental agony in the long years of creative work he gave to a single novel on the life of this hated and despised class. Balzac was consciously proud of his political views, of his royalism and Catholicism. The Goncourt brothers wrote in their Diary that their disillusionment in the good faith of politicians of all sorts brought them, in the end, to “a disgust in every belief, a toleration for any kind of power, an indifference towards political passion which I find in all my literary friends, in Flaubert as well as myself. You can see that one should die for no cause, that one should live with any government there is, no matter what one’s antipathy to it, and believe in nothing but art, confess no faith but literature.”

So many writers since, of considerably less talent than the two Goncourts and whose names cannot even be mentioned in the same breath with Flaubert, have professed (and still profess) a similar outlook, that it is worth our while to seek the origin of this apparent disillusionment and detachment from life. I say “apparent” because in Flaubert’s case at least (he was a great writer) there was no detachment, but a bitter battle to the death with that bourgeois society he hated so violently.

The Goncourts knew Balzac personally, their diaries are full of anecdotes about that vital and Rabelaisian genius. Flaubert, like themselves, also overlapped him in his creative work. Whence comes the great difference between the master and the disciples, a difference not in time but in outlook that divides them like a gulf? The energy engendered by the Revolution and its heroic aftermath had died out by the advent of Flaubert’s generation. The bitter struggle of classes and the real predatory character of capitalist society had become so clear that they aroused only disgust; whereas Balzac, still inspired by the creative force that built this society, sought only for understanding.

The democratic and Jacobin ideals of ’93, in the mouths of the liberal politicians of the nineteenth century, had become intolerable and monstrous platitudes. The real leveling character of capitalism was becoming apparent, its denial of human values, its philosophy of numbers that covered its cash estimate for all things human and divine. The old aristocracy whose corruption Balzac had drawn in such masterly fashion was nothing but a decayed shadow of its old self, an obscene ghost muttering and grumbling in the forgotten drawing-rooms of provincial country houses, or else indistinguishable from the new nobility of hard cash. Socialism, only known to Flaubert and his friends in its Utopian form, seemed to them as stupid and unreal as the worst extravagances of the liberal politicians who daily in word and deed betrayed their great ancestors. (That Flaubert considered them great ancestors there is plenty of evidence: “Marat is my man,” he writes in one letter.). Socialism was only another form of the general leveling of all values which so revolted them, and rendered the more disgusting because of its sentimental idealizing (it seemed to them) of the uneducated mob.

The period of 1848 saw the end of many illusions. Who after that bitter experience would ever again believe that fine words could butter parsnips? The June days, in which the Paris workers took the spinners of phrases at their word and fought in arms for liberty, equality, and fraternity, were the writing on the wall. Flaubert was a novelist, not a student of the social history and economic machinery of mankind, and to him the June days merely proved that flirting with empty slogans roused dark forces that were a threat to the very existence of civilized society. The dictatorship of the blackguard Louis Napoleon which followed was just a dictatorship of blackguards, the apotheosis of the bourgeois, and all that could be expected from the follies of preceding years. So the Education Sentimentale is a bitter and mercilessly ironical picture of the end of all the fine illusions of the liberal bourgeoisie, illusions which the red flag and rifle shots of June, 1848, shattered forever. After that, the vulgarity of the Empire. Nothing would be the same again, and one could resign oneself to the long process of social decay and destruction of civilization by this stupid and miserly bourgeoisie, with its wars, its narrow nationalism, and its bestial greed.

It might be thought that between Flaubert’s theory of god-like objectivity of the artist and Balzac’s theory of the natural history of social man, there is no great difference. In fact, there is all the difference in the world. Balzac’s scientific views were possibly naïve and incorrect, but in his view of life he was truly realist. He looked at human society historically, as something struggling and developing through its struggles. In Flaubert, life becomes frozen and static. After 1848, you could not observe and express life in its development because that development was too painful, the contradictions were too glaring. So life became for him a frozen lake. “What appears beautiful to me,” he writes to his mistress, “what I should like to do, would be a book about nothing, a book without any attachment to the external world, which would support itself by the inner strength of its style, just as the world supports itself in the air without being held up, a book which would be almost without a subject, or in which the subject would be almost invisible, if that is possible. The most beautiful books are those with the least matter. The nearer the expression comes to the thought, the more the word clings to it and then disappears, the more beautiful it is.”

ONCE this view was accepted, the way was clear for the new “realism” which took the slice of life and described it minutely and objectively. But life, of course, proved too restive a creature to slice up artistically, so the novelist grew finicking about the choosing of his slice, demanding that it be cut off such a refined portion of life’s anatomy that in the end he came to describe little more interesting than the suburban street or the Mayfair party. Revolting against the narrow view imposed on their vision by this theory, others drew their inspiration from Freud and Dostoievsky in order to give us the poetic picture of their own stream of consciousness. So in the end the novel has died away into two tendencies whose opposition has as little about it that is important to us as the medieval battles of the school-men.

Flaubert, however, was an honest man and a great artist. If his successors were content to avoid the task of mastering the reality of their age and substitute the “slice of life” or the subjective stream of consciousness, he was not prepared to make any such easy surrender. His letters are the confession of a most frightful struggle with a life, a reality, that had become loathsome to him, but which nevertheless must be mastered and given artistic expression. No man has ever raged against the bourgeoisie with the hatred of Flaubert. “I would drown humanity in my vomit,” he writes, and he does not mean humanity as a whole, but only the capitalist society of nineteenth-century Europe, immediately after the Paris Commune of 1871.

Letter after letter describes his struggle to find expression. He takes two months to write the tavern scene for Madame Bovary, the duration of which in the novel itself is only three hours. Over and over again he mentions that in the last month he has written some twenty pages. Can this be explained simply by his devotion to the perfect phrase, to the exact word? Is it an artist’s conscience which will be satisfied with nothing less than perfection in style? Hardly that. He himself says that the works in which the greatest attention has been paid to style and form are mostly second-rate, and in one place declares outright that he is not sure if it is possible to find a criterion for perfection in style. When he writes of the great authors of the world, it is enviously:

“They had no need to strive for style, they are strong in spite of all faults and because of them; but we, the minor ones, only count by our perfection of execution…I will venture a suggestion here I would not dare to make anywhere else: it is that the very great often write very badly and so much the better for them. We mustn’t look for the art of form in them, but in the second-raters like Horace and La Bruyère.”

Yet Flaubert did not live in physical and mental agony, shut up in his country home among people he despised, because he was a second-rate artist seeking formal perfection. No, he was a great and honest artist striving to express a world and a life he hated, and his whole artistic theory was the result of the compromise enforced on him in that struggle. “Art must in no way be confused with the artist. All the worse for him if he does not love red, green, or yellow, all colors are beautiful, and his job is to paint them…Look at the leaves for themselves; to understand nature one must be calm as nature.” Or again, the famous letter in which he sums up his credo: “The author in his work must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere; art being a second nature, the creator of this nature must act by similar methods; in each atom, in every aspect, there must be felt a hidden and infinite impassibility.”

FLAUBERT himself failed utterly to live up to his precepts. Such a god feels neither love nor hate. Flaubert’s whole life was animated by hate, a holy hatred of his age which was a kind of inverted love for man deceived, tormented, and debased by a society whose only criterion of value was property. He gave his view of that society at last in the irony of Bouvard and Pécuchet, a novel which arose out of his scheme for a Dictionary of Accepted Ideas in which you were to find “in alphabetical order on every possible subject everything which you need to say in society to be accepted as a respectable and nice fellow.”

Flaubert, like Dickens, was a great writer faced with the problem of giving a true picture of a society whose very premises were rapidly becoming a denial of the standards of humanism once looked on as our common heritage. Dickens solved his problem by the compromise of sentimental romanticism. English conditions made it inevitable for him. Flaubert, who lived in the France of June 1848, of the Third Empire, the Franco-Prussian War, and the Commune, had to take another road. Not only his own temperament, his uncompromising honesty, forbade the path of sentimentality (how easy that would have been for a less great man, Daudet was to show), but the harsher reality of French life irrevocably closed that path for him. He stood apart from the struggle, with infinite pain created for himself an unreal objectivity, and tried to isolate by means of a purely formal approach, certain aspects of life. Poor Flaubert, who suffered more terribly than any writer of his time in his effort to create a picture of life, who more than any man felt the real pulse of his age, yet could not express it, this man of deep passion and intense hatred, has suffered the sad fate of becoming that colorless thing, the highbrow’s example of the “pure artist.” Why we should admire a “pure artist” more than a “pure woman” is one of the mysteries of the age. Why not just an artist, and a woman? They are both interesting and they both suffer, but not in order to be beautiful.

There was one contemporary of Flaubert’s who went through the same agony of creation, who tormented himself for weeks in order to find the precise words to express the reality he was determined to dominate and refashion in his mind. This other artist wrote and re-wrote, fashioned and refashioned, loved and hated with an even greater intensity, and finally gave the world the mighty fragments created by his genius. His name was Karl Marx and he successfully solved the problem which had broken every other of his contemporaries, the problem of understanding completely the world of the nineteenth century and the historical development of capitalist society.

“From form is born the idea,” Flaubert told Gautier, who regarded these words as being “the supreme formula” of this school of “objective” realism, worthy to be carved on walls. Content determines form, was the view of Marx, but between the two there is an inner relationship, a unity, an indissoluble connection. Flaubert’s ideal was to write a book “about nothing,” a work of pure formalism, in which the logical was torn apart from the factual and historical. In its extremest form, as developed by Edmond de Goncourt, Huysmans, and others, this became a pure subjectivism, which converted the object into the passive material of the subject, the novelist, who in turn was reduced to a mere photographer.

Lafargue, Marx’s son-in-law and a keen critic of the French realists, has contrasted the two methods:

“Marx did not merely see the surface, but penetrated beneath, examined the component parts in their reciprocity and mutual interaction. He isolated each of these parts and traced the history of its growth. After that he approached the thing and its environment and observed the action of the latter upon the former, and the reverse. He then returned to the birth of the object, to its changes, evolutions, and revolutions and went into its uttermost activities. He did not see before him a separate thing for itself and in itself having no connection with its environment, but a whole complicated and eternally moving world. And Marx strove to represent the life of that world in its various and constantly changing actions and reactions. The writers of the school of Flaubert and Goncourt complain of the difficulties the artist encounters in trying to reproduce what he sees. But they only try to represent the surface, only the impression they receive. Their literary work is child’s play in comparison with that of Marx. An unusual strength of mind was called for in order to understand so profoundly the phenomenon of reality, and the art needed to transmit what he saw and wished to say was no less.”

Lafargue rightly estimates the creative method of Marx, and correctly shows the deficiencies of Flaubert’s method, though he does not understand that Flaubert himself in his heart of hearts was aware of its deficiencies. Neither does Lafargue realize the forces which drove Flaubert and the Goncourt brothers to adopt their artistic method. The diary has some interesting light to throw on this last point. In 1855, Edmond writes that “every four or five hundred years barbarism is necessary to revitalize the world. The world would die of civilization. Formerly in Europe, whenever the old population of some pleasant country had become suitably affected with anæmia, there fell on their backs from the North a lot of fellows six feet tall, who remade the race. Now there are no more barbarians in Europe, and it is the workers who will accomplish this task. We shall call it the social revolution.”

In the midst of the Commune he remembered this prophecy.

“What is happening [he wrote] is the complete conquest of France by the working-class population, and the enslavement of noble, bourgeois, and peasant beneath its despotism. The government is slipping out of the hands of the possessing classes into the hands of those with no possessions, from the hands of those who have a material interest in the preservation of society, into the hands of those who have no interest in order, stability, and conservatism. After all, perhaps in the great law of change of things here below, the workers, as I said some years ago, take the place of the barbarians in ancient society, the part of convulsive agents of destruction and dissolution.”

Neither Flaubert nor the Goncourts saw the working class as anything but a purely destructive agent. They did not suffer from any illusions about bourgeois society, they hated its greed, its narrow nationalism, its lack of values, its general leveling tendency and degradation of man, but they saw no alternative to this society, and here is the fundamental weakness of their work. After Flaubert, critical realism could progress no further, for his tremendous labors had exhausted the method. Either the novelist must again see society in movement, as Balzac had done, of he must turn into himself, become completely subjective, deny space and time, break up the whole epic structure. There was also a further difficulty, one that had been growing for more than a hundred years, and was now reaching its acutest tension, the difficulty of a unified outlook on life, of the ability to deal with human character at all.

The great novelists of the Renaissance had not felt this difficulty. For them, humanism had given direction to their ideas and inspired their work. The Renaissance produced its great philosophers, though at the end of the period rather than the beginning, in Spinoza, Descartes, and Bacon. Certainly, even here the main division in human thought is apparent in the conflict of Descartes and Spinoza, but in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was not yet so violent as to destroy all philosophic unity. The English and French realist novelists on the whole had a similar view of life, their work in consequence gains in completeness and force. In the nineteenth century, however, the period when all the violent contradictions of the capitalist social system become clear, when wars and revolutions destroy the last feudal strongholds in Europe and the modern nations are formed, there is no longer any philosophical unity. Kant and Hegel have so developed idealism that it temporarily overwhelms the realist, materialist philosophies. The century is one without a unified view of human life, so that it becomes more and more difficult for the novelist to work except in a minor, specialized way, by isolating some fragment of life or of individual consciousness. Flaubert’s letters are full of this feeling, and he describes his vain efforts to master the philosophers, his rifling of the works of Kant, Hegel, Descartes, Hume, and the rest. All the time he feels the desire to get back to Spinoza, as the Goncourts felt the desire to get back to the dialectic thought of Diderot. But in the end they give up the search for a philosophical basis as being impossible of fulfilment in the contemporary world.

It is the tragedy of Flaubert and his school that they so continually and acutely felt their own insufficiency, were so conscious of the great superiority of the masters of the past, Rabelais, Cervantes, Diderot, and Balzac. Sometimes they almost blundered on the reason for this, and there is a passage on Balzac in the Goncourt diary which comes so close to the truth, and is so significant for the writer today, that it will perfectly sum up the argument.

“I have just re-read Balzac’s Peasants. Nobody has ever called Balzac a statesman, yet he was probably the greatest statesman of our time, the only one to get to the bottom of our sickness, the only one who saw from on high the disintegration of France since 1789, the manners beneath the laws, the facts behind the words, the anarchy of unbridled interests beneath the apparent order, the abuses replaced by influences, equality before the law destroyed by inequality before the judge, in short, the lie in the program of ’89 which replaced great names by big coins and turned marquises into bankers–nothing more than that. Yet it was a novelist who saw through all that.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v23n07-%5b08%5d-may-11-1937-NM.pdf