A primer if, like me, you are a little flummoxed in understanding the factional disputes in the Communist Party fought over the Farmer-Labor Party in the mid-1920s. A leader of one of those factions gives their view on the F.L.P. projects, containing such weighty issues as notions of class independence, relations of the working class to farmers, the role of the Communist Party, ‘stages’ of development, a ‘labor aristocracy,’ and possibilities for revolution in an expanding empire. For decades Bittleman was a close ally of William Z. Foster and in the mid-20s a leader of the Foster-Cannon faction against the Ruthenberg-Lovestone-Pepper faction.

‘Farmer-Labor Party in Retrospect’ by Alexander Bittelman from Workers Monthly. Vol.

A CRITICAL REVIEW OF OUR PAST LABOR PARTY POLICY IN THE LIGHT OF THE PRESENT SITUATION.

On November 6, 1924, the Central Executive Committee of the Workers Party made public a statement on the results of the presidential elections in which it says:

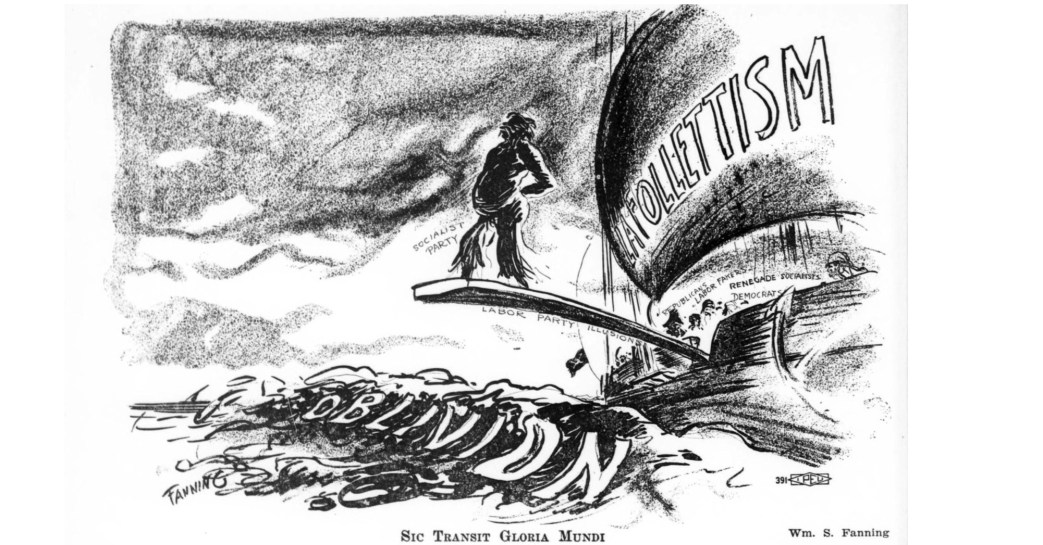

“The demonstrated weakness of the LaFollette movement, as compared to the pre-election estimates of all sides, not only seriously retards the development of the so-called “third party,” but also completely eliminates the immediate possibility of the growth of a mass farmer-labor party of industrial workers and poor farmers, distinct from the Workers Party. A general agitation campaign by the Workers Party under the slogan of “For a Mass Farmer-Labor Party,” would not be profitable or successful. The policy of applying the united front tactic by attempting to form a mass farmer-labor party of which the Workers Party would be a part, is not adaptable to the present period. Our chief task in the immediate future is not the building of such a farmer-labor party but the strengthening and developing of the Workers Party itself as the practical leader of the masses and as the only party that represents the working-class interests and knows how to fight for them. The best means to this end is to agitate and fight for the united front from below with the rank and file workers in their daily struggles, in the spirit of the Fifth Congress of the Communist International.”

This marks a departure in the tactics of our party. It means that we no longer hold to the idea that a farmer-labor party is the only or the most effective way of developing independent political action by the working masses of America. The November 6 statement of the Central Executive Committee says in effect that in the present situation, and in view of the political changes that have taken place in America during the last six months, the better way, the more effective way of developing and enhancing the class-struggle on the political as well as on the economic field is for the Workers Party itself to enter into United Front alliances with the rank and file of the workers and poor farmers on the basis of their immediate daily struggles against capitalist exploitation. Or, putting it somewhat differently, that the task of our party now is not to assist in the creation of a new political party—a farmer-labor party—but to popularize itself as the leader of the proletarian class struggle by means of the United Front tactics applied mainly from below.

The Same Strategy But Different Tactics

This is merely a change in tactics, but not in strategy. The strategic aim of our party is now the same as it has been for the last two and a half years. What has been our main strategic aim? We all know it. It can be formulated in one short sentence. It is this:

To develop independent political action of the working masses under the leadership of the Workers (Communist) Party.

In pursuit of the above end the Workers Party had adopted some two and a half years ago the tactic of a Labor Party. That is, the campaign for a farmer-labor party was to serve as a means towards awakening the political consciousness of the working class, towards crystallizing this consciousness into organized struggles and towards establishing the Workers (Communist) Party as the leader of these struggles. In other words, the Labor Party policy was a tactical method, a means towards an end.

This end—independent political action of the working masses under the leadership of the Communist Party—still remains the chief strategic aim of our party, only the tactical means must be changed because of the changed political situation. Our old farmer-labor party policy is no longer good. We must therefore find other tactical means for the achievement of our strategic aim. These new tactical means can be formulated as follows: A united front with the rank and file from below on the basis of their daily immediate struggles, with the Workers Party itself, and under its own name, striving to win leadership.

It is not the purpose of this article to enter into a detailed discussion of this main proposition, but rather to restore the historical background from which we started out on our labor-party policy. For it is only through a clear understanding of the origin and development of our old tactics that we can arrive at a correct formulation of our new tactics.

When and How Did We Get the Labor-Party Idea?

Thus the first question to be answered is, when and how did we arrive at our first labor-party policy?

It was in the winter of 1922. The Workers Party had then just been formed, which was the first successful breach in the wall of isolation that had surrounded the American communist movement since it had been driven underground by the White Terror of 1919.

Having made its first break into the open the American communist movement was confronted with the next task of establishing contact with the masses in their daily struggle. The first convention of the Workers Party, held in New York in December, 1921, had already formulated an industrial program which provided our party with an effective means for establishing contact with the masses mainly on the economic field. It was therefore necessary to devise some additional measures for establishing contact on the purely political field.

The first Central Executive Committee of the Workers Party was looking for an outlet to the main field of the class struggle and it was asking itself: Where can that outlet be found? After a number of hesitating, half measure steps, we finally adopted, in the spring of 1922, our first labor-party policy.

Why a labor-party policy? There were four chief facts that that determined our action. I shall enumerate them in the order of their comparative importance.

First–The strong movement from below, from the ranks of labor and poor farmers, towards the formation of a farmer-labor party.

Second–The formation of the “Conference for Progressive Political Action” (C.P.P.A.) at a Conference of railroad and other unions held in Chicago in February, 1922.

Third–The United Front tactics of the Communist International.

Fourth–Lenin’s advice to the British Communists to fight for admission into the Labor Party.

The first two facts–the existence of a distinct rank and file farmer-labor movement and the formation of the C.P.P.A.–were taken by us to mean, and rightly so, that there was on foot a mass-movement of workers and poor farmers, seeking independent political expression through some sort of a Farmer-Labor Party. The C.P.P.A., which was from its very inception a movement of labor leaders, we interpreted as a result mainly of the same rank and file pressure. We were therefore confronted with the following problem. What shall be our attitude towards this movement for a farmer-labor party? Shall we remain indifferent to it, shall we oppose it, or shall we step into it?

It was the general feeling in the Central Executive Committee of the Workers Party that we cannot oppose this movement because, whatever its shortcomings, it marks a step in advance by the working masses. We also felt that we cannot very well remain indifferent to a political mass-movement involving large masses of workers and poor farmers. Then the only alternative was to become part of it, and to fight within for the principles of class-struggle and Communism.

But to accept this latter alternative in the beginning of 1922, when our party was still half submerged in the sectarian prejudices of its early days, meant so violent a departure from accepted tactics that the Central Executive Committee did not venture to risk it. And only after the party became more intimately familiar with the United Front tactics of the Communist International, and particularly, with Lenin’s advice to the British Communists, to fight for admission into the Labor Party, did the C.E.C. finally feel justified in adopting a complete thesis which committed the party to a labor-party policy.

The Essence of our First Labor Party Policy

I quote from the thesis on the United Front adopted by the Central Executive Committee in the early summer of 1922; Paragraph 9:

“The creation of a United Front of Labor on the political field in the United States is the problem of the development of independent political action of the working class. The working class of Europe has for a long time participated independently in political activities. Not so in the United States. Here the problem is not to unite existing political groups and organizations for common action but to awaken political class consciousness among the workers.” The above states our main strategic aim in terms of the United Front tactics of the Communist International. It is formulated correctly. The principle enunciated in this formula holds true to this very day. But taken by itself it does not yet mean that we must have a labor party. The road to independent political action by the masses does not necessarily and under all conditions lie through a Farmer-Labor Party. It is only under certain specific conditions that a labor party becomes the possible and desirable channel for mass political action by the working class. These conditions are, roughly speaking, two. One is negative, the other is positive.

One–The absence of a revolutionary mass-party of the workers.

Two–The presence of a strong mass-movement toward a farmer-labor party.

The second condition is the most important, and it was strongly in evidence when we adopted our first labor party policy. I quote further from paragraph 9 of the thesis:

“The class struggle has reached such a degree of intensity here that every battle of the workers reveals the political character of the struggle that is teaching the proletarian masses the necessity for class conscious political action. The numerous efforts of all kinds of labor organizations to form a labor party in the United States is evidence of this fact. These efforts indicate a step forward in the progress of the class struggle toward revolutionary working class action. To oppose this tendency toward the formation of a labor party would be folly.”

Mark the last sentence which says we cannot oppose the movement toward the formation of a labor party. It is the most vital point in the whole thesis. It means that in the beginning of 1922, we were confronted with a movement which compelled the Workers Party to take an attitude, and that the attitude could not be one of opposition. Consequently, when we now discuss the question whether we still need a labor party policy, we must bear in mind that there is at present no movement for a farmer-labor party to compel the recognition, support or opposition of the Workers Party. In other words, there is at present no such mass-movement as existed in 1922 to compel our party to assume an attitude. The problem of what we shall do with the farmer-labor movement no longer exists now. But it existed in May, 1922. There was in the field a strong labor-party movement. That’s why the thesis said:

“To make the labor party an instrument of the class struggle and the revolution the participation of the Communists is an imperative necessity. It is not in the interests of the proletarian revolution nor can the Workers Party assume responsibility for the latent political power of the workers remaining dormant. The party must not oppose the coming to life of this power because it has not yet the standing and influence among the masses to set it at work in the name of and for the purpose of Communism.”

The British experiences also had their share of influence upon our decision. We saw the coming into existence in the United States of a labor party of which we shall want to become a part. We also knew the difficulties that the British Communists were having in securing admission into the British Labor Party. To forestall such eventuality in the United States, we thought it the better part of wisdom to become part of the movement while it was still in its formative stages. We therefore said in our thesis:

“To promote the development of the political action of the working class into revolutionary action the Communists must become factors in the labor party that may be formed. We can achieve this end only if we anticipate the formation of such a party and now adopt a policy thru which we will become established as a force in the political struggle of the workers and thus an important factor in the labor party. The participation in a United Front in local political struggles will give us a strong position in relation to the labor party.”

A Party Based on the Unions

It was the general conception of our party that the Labor Party which we thought was coming into existence will be a political organization based upon and formed by the trade unions. Not necessarily by the Gompers crowd but by the bulk of the unions just the same. This was our basic idea of how the farmer-labor party will come into existence. Our party expressed that idea quite clearly in its statement “For a Farmer-Labor Party,” written by comrade Pepper and issued in October, 1922. I quote from the statement.

“We understand, of course, by a Labor Party no renaming of bankrupt, disintegrating parties, nor a quiet refuge for effete politicians, but a great mass organization formed by organized labor.”

And further:

“A Labor Party will grow because of its formation by the organized workers. A Labor Party would deserve that name only if it were formed by the trade unions. A Labor Party of any other form would be a mere caricature, a political swindle, and a miscarriage. A Labor Party should be launched only if it is created by the trade unions.”

The foregoing demonstrates the following propositions;

1. The main strategic aim of the Workers Party has been and is the development of independent political action of the working masses in the direction of the revolutionary class struggle and under its own leadership.

2. As a means towards this end the Workers Party adopted in the early part of 1922 a labor party policy, because there was then in existence a strong mass movement for a farmer-labor party.

3. This farmer-labor party was conceived by our party as an organization based upon and formed by the trade unions.

4. The Workers Party conceived of its immediate role in the farmer-labor movement as that of a left wing whose function it would be to drive the movement as a whole in the direction militancy and determination in the class struggle.

5. The immediate tactical objective of the Workers Party under those conditions was to connect itself with the growing farmer-labor movement, to get on the ground floor of it, so that when the National Farmer-Labor Party is formed we can be a factor in it for the furtherance of the principles and policies of Communism.

It is well to recall these propositions now, when we are again discussing the question whether we must have a labor party policy. Go back to the origin of the problem. And when you will find that the whole problem arose out of an existing and growing movement for a farmer-labor party, you will undoubtedly ask yourself: What is the situation today? Is there at present such a movement, and if not, is it likely to arise in the immediate future?

And since you are bound to come to the conclusion that there is no such likelihood, you will agree with the position of the Central Executive Committee that the present situation calls for neither a labor party policy nor a labor party slogan.

The “Chicago” Orientation

The first serious departure from our original labor party policy, as expressed in the thesis of May, 1922, was made by the Central Executive Committee of the Workers Party soon after the Cleveland Conference of the C.P.P.A. which convened on December 11, 1922. What did this departure consist of?

It consisted in this, that after the December meeting of the C.P.P.A. we began orientating ourselves on the Chicago Federation of Labor and on Fitzpatrick’s Farmer-Labor Party. That is, we adopted a new conception of how the labor party was to come into existence. Prior to the December meeting we adhered to the idea that the Labor Party must be based upon and formed py the entire organized labor movement of America, not one section of it but substantially the whole. And our own role in this movement we conceived to be one of propaganda mainly, that is, the labor party to us was chiefly a propaganda slogan.

After the December meeting of the C.P.P.A. we began thinking in terms not of propaganda alone but also of organizational and political manoeuvres designed to bring about the actual formation of a Farmer-Labor Party. The tactical means to this end was to be an alliance or United Front between the Chicago Federation of Labor and Fitzpatrick’s Farmer-Labor Party on the one hand and the Workers Party with its sympathizing organizations on the other hand. It is in this sense that I designate this period (January to September, 1922) as the period of our “Chicago” orientation.

The essence of this new orientation is well expressed in Comrade Pepper’s analysis of the December meeting of the C.P.P.A. I quote from chapter VII of his pamphlet (second edition): “For a Labor Party.”

“From the point of view of the class-struggle we have the following groupings within the labor movement, after the Cleveland Conference: 1. Gompers and the official A.F. of L., in alliance with the capitalists, in the form of support of the official Republican and Democratic parties. 2. The bureaucracy of the railroad labor organizations, of the United Mine Workers and the Socialist Party, in alliance with the lower middle class and the well-to-do farmers, in the form of support of the LaFollette third party movement. 3. The Chicago Federation of Labor and a number of other state federations, the Farmer-Labor Party, the Workers Party and the poor tenant and working farmers dissatisfied with the lukewarm policy of both the LaFollette group and the Non-Partisan League. These are the forces for an independent class-party of the laboring masses, for a Labor Party.“

The idea is very simple. Here is the organized labor movement of America. Gompers is with the capitalist parties. The bulk of the C.P.P.A. is with LaFollette and the third party. The only section of the labor movement that is in favor of a Labor Party is the Chicago (Fitzpatrick) group and the Workers Party. Let the two unite and form the Labor Party.

The thing that is wrong with this all-too-simple scheme is not the facts upon which it is based but its conclusions. Just think of it! When you find that Gompers, who stands for the ruling power of the A.F. of L., and the bulk of the C.P.P.A., which stands for the ruling power in the largest unions outside the A.F. of L., are both opposed to a Labor Party and are able to drag along with them or to prevent the expression of the rank and file, doesn’t it suggest to you the idea that the organized labor movement is not yet ready for a Labor Party? Of course, it does. And the only justifiable conclusion to be drawn from this fact would have been the following: Either to discard the labor party idea altogether, or, if it still possessed appealing force to large masses, continue it merely as a slogan. The latter conclusion would have been the correct solution of the problem as it presented itself after the December meeting of the C.P.P.A. This correct conclusion we failed to make and by this failure committed a fundamental error in tactics for which the writer of this article is willing to assume as much blame as is due him as a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Workers Party.

We made a wrong switch by imagining that the Workers Party and the Chicago group present a wide enough basis for the immediate formation of a Labor Party. All our other mistakes, such as the split at the July 3 Convention over the immediate formation of a Farmer-Labor party, were the logical result of this wrong turn, the premature departure from the May, 1922 thesis, taken by our Party after the December meeting of the C.P.P.A.

A Theory to Justify A Mistake

The mistake became apparent to nearly everyone in the party soon after the July 3 Convention. The minority in the old Central Executive Committee (of the term 1923-1924) was ready to retrench and straighten out the wrong twist in our tactics. But not so the majority. The latter was determined at all costs to justify the departure in policy begun in December, and completed in July, 1923, and went even to the extent of producing a new labor-party “theory” to justify its actions. This new theory was incorporated in the now famous “August thesis,” which was adopted by the majority in the former Central Executive Committee at its full meeting on August 24, 1923.

What was this new theory? I quote the August thesis: “The development of the Labor Party in America takes a different direction from that in Great Britain. The British Labor Party was formed…from above by the officials of the trade union movement.”

Not so in America.

“The Labor Party movement in the United States today is a rank and file movement…The July 3rd convention revealed the fact that the big International unions did not come, that only local unions and city central bodies were represented, that in fact the labor party today is a rank and file proposition. It also showed another fact, namely, that the rank and file is permeated with communist influence.”

The July 3rd convention also proved that:

“Not a single organized political group outside of the Workers Party exists today which wishes to take up the fight for the Labor Party on a national scale.”

Consequently,

“The Workers Party has the historical task of becoming the leader of the labor party movement in America.” And as additional proof for this “theory” we find in the thesis the following statement:

“In America we have a number of political groups which fight for influence within the trade union movement. The attempt to gain influence upon the workers assumes in America the organizational expression of forming various labor parties. The Socialist Party tries to form a labor party. The old farmer-labor party tries to form another labor party, the Workers Party has helped in the formation of the Federated Party.”

The above is the very heart of the new revelation. Each political group tries to build its own labor party. Therefore, the Workers Party must also have a labor party of its own. And what will the labor party be? Well, it may take either of two forms:

“Its development may be the nucleus around which the mass party of labor will be formed or as a mass Communist party.”

That is, if luck is with us our Federated may become the real mass labor party, or if luck goes against us, no need to worry, we can take the Federated and make it a mass Communist party. The masses are there in both cases, on paper, at least.

I do not intend here to go into this theory of multiple labor parties further than to say the following three things. First, that it was a complete negation of our May, 1922, thesis and of our first statement “For a Labor Party” published in October, 1922, which were based on the idea that a labor party is a political organization based upon and formed by the organized labor movement. Second, that if this “theory” were put into effect it would have spelt the liquidation of our Workers (Communist) Party in favor of a non-Communist party. And, third, that this new revelation was fabricated for no other purpose than to justify an essentially wrong tactical move.

As against the liquidating tendencies of the August thesis, which were tacitly accepted by the former majority even at the November meeting of the Central Executive Committee, the minority presented a thesis of their own introduced by Comrades Foster and Cannon. In that document the minority took the following position. I quote from the Foster-Cannon November thesis.

“We hold that our most important revolutionary task is the building of a mass Communist Party, based upon individual membership, which is the Workers Party. The building of a Labor party not only must not interfere with but must directly assist this process.”

“The August thesis makes the argument that the F.F.-L.P. can be developed into a mass Communist party. There is no foundation for such an assertion. The conditions for the building of a mass Communist party are the existence of a closely-knit Communist nucleus operating within the broadest mass organizations of the workers, permeating them with its doctrines and sweeping the most advanced of them into its ranks. The Workers Party is such a Communist nucleus, and the naturally developing Labor Party movement is such a mass organization.

By working within this mass organization and pushing it forward, the Workers Party is bound to expand and extend its influence. The organization of the Federated Farmer-Labor Party does not facilitate this development, but interferes with it. Wherever it takes organizational form it separates the Communists and their closest sympathizers, from the main body of the movement and creates the conditions for a sectarian Communist Party controlling a sectarian Labor Party.”

And further:

“Our position is not based on the assumption that the entire labor movement must join the Labor Party at once, or that even a majority is necessary. But we hold that wherever it is formed, it must unite the Labor Party forces and have a genuine mass character. We want it to be organized upon as broad a base as possible with as large a mass of workers as can be gotten together upon the issue of a Labor Party, and not merely those who can be organized on the issue of Communism which is raised by the Federated Farmer-Labor-Party. Our militants should endeavor to take a leading part in all these mass parties, entrench themselves in strategic positions, and lead the workers by degrees to the platform of Communism.”

After a long and protracted debate at the November meeting of the Central Executive Committee, resulting in a semi-official conference between representatives of majority and minority, it was finally agreed that a representative of the majority would make such a statement of interpretation of their November thesis as will definitely dissociate it from the August thesis and will thereby enable the minority to vote for the majority proposition.

The statement that was made was very unsatisfactory, yet the minority voted in favor of the majority proposal because, as Comrade Foster declared at the meeting (I quote from the official minutes of the November meeting of the C.E.C.):

“Although not in agreement with the Pepper-Ruthenberg thesis he thought that, in view of the interpretation put upon this thesis, it provided a working basis, and that for unity’s sake no good would be served by continuing to insist upon the thesis of Cannon and himself.”

Due to the criticism and pressure of the minority in the former Central Executive Committee (majority of present C.E.C.) the August thesis was put in cold storage. The policy actually pursued between August, 1923 and January, 1924 was a sort of compromise between the views of majority and minority. It was a policy of retaining the Federated Farmer-Labor Party mainly as a propaganda instrument for a labor party and as a means of establishing organizational contact with other farmer-labor groups for the furtherance of the movement as a whole.

Naturally, we were looking for new allies. The break with the Fitzpatrick group removed the foundation from our old United Front which I designate as the “Chicago” orientation. And in this quest for allies it was also natural for us to turn to the Farmer-Labor Party of Minnesota and to the other farmer-labor groups of the Northwest (North and South Dakota, Washington, Montana, etc.) These were the only organized farmer labor groups that were tending in the direction of a National Farmer-Labor Party.

Our Northwestern Orientation

Our base of operations was gradually shifting to the Northwest with Minnesota as the center. The tactics pursued by the Workers Party during that period (September 1923—June 1924) were based on the following idea: That the Workers Party, through the Federated and in alliance with the farmer-labor groups of the Northwest, would constitute a base wide enough for the creation of a National Farmer-Labor center to command the recognition of large masses.

The most vulnerable spot in this orientation was the predominance of farmers over industrial workers in the farmer-labor organizations of the Northwest. These organizations were incomparably closer ideologically to LaFollette and the third-party movement than to our conception of a class farmer-labor party. This we found out very soon and thereupon decided to organize, within the general farmer labor movement, distinct and separate blocks of industrial workers and the poorest farmers. The working out of this policy could best be studied in the functioning of the Farmer-Labor Federation within the Farmer-Labor Party of Minnesota.

Very soon we were confronted with the problem of combatting the influence of LaFollette. Since practically the whole farmer-labor movement of the Northwest—and there was no other outside the Northwest—was ideologically a LaFollette movement, and since we were basing our labor party policy mainly on that movement, we were compelled very early in the season to consider the probable effects upon that movement should LaFollette be a candidate for president.

Our decision in November, 1923, somewhat modified in March, 1924, to enter into an alliance with the third-party movement, under certain specified conditions, even to the extent of supporting LaFollette for the presidency, was designed exclusively as a manoeuvre to combat LaFollettism and to save the farmer-labor elements for a farmer-labor party.

This manoeuvre was not carried out to the full extent. First, because shortly before the St. Paul convention of June 17, LaFollette declared open war upon the farmerlabor movement, thereby creating a situation totally incompatible with any alliance between the two. And, second, because our party accepted the advice of the Communist International not to enter into an alliance with the third party movement nor to support the independent candidacy of LaFollette.

In the light of what transpired between June, 1924, and today, it is perfectly clear that our decision to enter into an alliance with the third-party movement was a mistake even from the point of view of tactics. Neither an alliance with the third-party movement, nor our willingness to support LaFollette, would have saved the farmer-labor movement from destruction by the LaFollette forces. Why? For one reason mainly. Because the farmer-labor movement, which we wanted to save from being swallowed by LaFollette, was substantially a LaFollette movement. To save it from LaFollette meant to win it for class-struggle which, under the prevailing conditions, was the same as accepting the leadership of the Workers (Communist) Party. And such a step the farmer-labor movement of the Northwest, predominantly agrarian and petty-bourgeois, was very far from being ready to take. Our wrong decision with regard to the third party movement, later corrected by the Communist International, was a direct result of our orientation upon the farmer-labor movement of the Northwest which was substantially a LaFoilette movement. We attempted to save a farmer-labor soul which didn’t exist and in the process we nearly lost our own Communist soul.

The Orientation on the Workers Party

July 8, 1924, will stand out as a historic date in the annals of our Party. It was on that day that the Central Executive Committee decided, upon the initiative of Comrade Foster, to enter the election campaign as the Workers Party on its own program and with its own candidates. By this decision the Central Executive Committee gave recognition to the fact that there was no farmer-labor movement in existence to justify or demand a United Front in the elections.

We came back to firm ground. For once after a long, long while we were again operating with realities instead of with fiction. Behind this decision of the Central Executive Committee there was a deep realization of the truth that it is the duty of a Communist party always to stand in the forefront of class struggle and in its own name approach the masses with its message and slogans, that the United Front tactics were designed to bring us into contact with masses in their daily struggles and not with ourselves alone under another name. The decision of July 8 was a turning point in the direction of realism, self-criticism, and correct Communist tactics.

In looking over our labor party activities for the past three years, we find that we started out right. We didn’t think it was our duty to form new political non-Communist parties. We were confronted with a strong mass sentiment, in some places even a movement, for a labor party, and we decided to join that movement and to function within it as its most conscious and militant wing. That was correct. To this idea we should have stuck.

But Fate and the former majority of the Central Executive Committee decided that, because John Fitzpatrick and his Chicago group were mildly in favor of a labor party, it was the duty of the Workers Party to begin a determined fight for the immediate formation of such a party. This was wrong. Instead of a labor party based upon and formed by the organized labor movement, it produced the split of July 3 and the Federated Farmer-Labor Party which proved neither federated, nor farmer-labor nor a party. It produced an organization which threatened to liquidate our own Communist party. It also produced the August thesis.

The worst did not happen, because of the criticism and pressure of the former minority (now the majority), but our tactics continued twisted and wrong. Why? Because the debacle of July 3 drove us to the orientation on the Northwest and this in turn pulled us into the compromising policy of the third-party alliance. Which is the same as saying, that the rush of the former majority to “assume leadership” in the farmer-labor movement was the origin and main cause of most of our major mistakes on and since July 3.

We shall now have no labor party policy because there is no farmer-labor movement. We shall also have no labor party slogan because such a slogan will now have no dynamic appeal and will offer no basis of struggle to the masses of workers and poor farmers. But we will have United Front campaigns, on the political field (not only in elections) as well as on the economic field, on the basis of the immediate struggles of the working masses. Thus we shall build our own Workers Party into a powerful mass Communist Party.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1924/v4n02-dec-1924.pdf