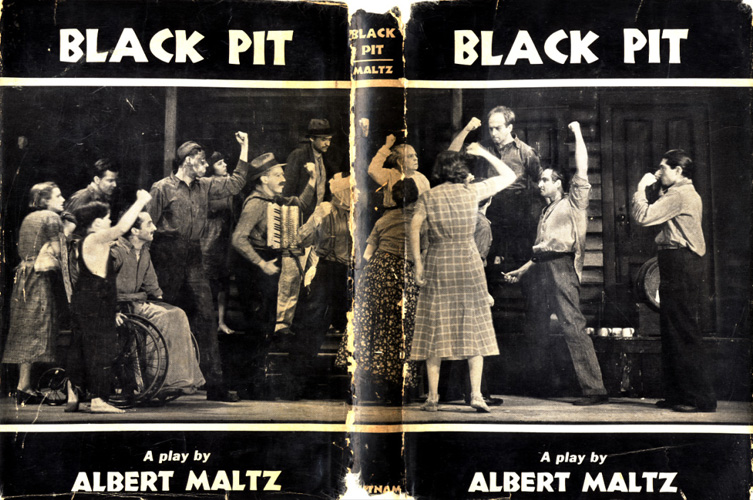

Sounding far better than ‘On the Waterfront,’ Herbert Kline reviews Albert Maltz’s play of a worker trapped into becoming a stool-pigeon, The Black Pit.

‘The Black Pit’ by Herbert Kline from New Theatre and Film. Vol. 2 No. 4. April, 1935.

“t’ree ‘clock come, I go wurk in pit come out twelve ‘clock night, take’m wash, eat leely bit, go, sleep…come five ‘clock morning, whistle blow, catch breakfast, smoke leely bit, rest leely bit…after while catch’m couple hour more sleep…den wurk again…live lak dis all my life…”–Steve Kristoff, since dead from a fall of slate.

HERE, in the drama of a worker who betrays his class, is an important and highly original departure in working-class plays. Albert Maltz has to his credit our first revolutionary tragedy.

The Black Pit dramatizes the kind of life described above by Steve Kristoff. Unlike Peace On Earth and Stevedore, this new Theatre Union play is not a thrilling stimulus to action, though the need for militant struggle is emphasized in a clear cut revolutionary line throughout. Rather, it is a morality play of the proletariat, the moral tragedy of Joe Kovarsky, a militant young Slovak miner who weakens under the relentless, crushing, piling-up of disaster after disaster, and ends by becoming a stool-pigeon. The tragedy, centering upon the moral issues involved more than upon the fatal consequences of the stool-pigeon’s crime, is told with such understanding artistry that only a few sectarians, missing the point completely, mistake the human portrait of a man who is crushed by the system and by his own weakness for what they foolishly call “the glorification of a stool-pigeon.”

As the play opens Joe Kovarsky is taken from the arms of his young bride Iola to serve a term in prison on a trumped up charge of having blown up a tipple during a strike. When he returns three years later, he finds that he has left one prison for another. His brother Tony has been crippled in a mine accident. Tony, his wife and children, and Iola have all been living on the $10.50 per week “compensation” awarded the paralyzed miner by the coal company. A company union controls the patch and conditions are worse than ever. Like every other miner with a strike record Joe is on the “blacklist.”

After months of searching, Joe finally finds. work under an assumed name. The miners are herded together in boarding houses that “stink like hell.” They carouse and gamble on Saturday nights, throwing away their hard earned pay to forget the loneliness and squalor of their lives in drunkenness and vice. One of the most exciting moments in the play comes when the miner Bakovchen leaps across the room to warn the newcomer against being drawn into conversation by a “stool-pigeon.” But Bakovchen’s comradely warning does not matter, for a moment later, the Super, having discovered Joe’s real identity and record, fires him.

Upon his return home, Joe finds that Iola, as the wife of a blacklisted miner, cannot be attended to by the company doctor, even in childbirth. The Super offers to get the company 20 doctor for Iola if Joe will accept a job as stool-pigeon.

Joe refuses contemptuously and Mr. Prescott leaves. And when his wife cries out her fear that, like her mother before her, she will die in childbirth for want of a doctor, Joe yells:

“What you wan’–me be stool-pigeon…tink I no wan’ job–no wan’ eat–no wan’ have dochtor? Tink I wan’ you to have baby maybe die?”

In desperation, when his wife suggests that he fool the Super by “just pretending” to be a stool-pigeon, Joe grasps at this straw and decides to take the job just long enough to get the doctor for Iola, and a few dollars to get away on afterwards.

ALTHOUGH he is determined not to tell anything of importance, he is trapped by Prescott (in the one phony and wholly unnecessary scene in the show–the good old dictaphone is called upon to turn the trick-again!) He is forced to lie to his fellow workers when a strike is imminent as a result of the miners’ suspicions that the mine is “hot” and liable to explode. Not only do his lies persuade the miners to return to the dangerous mine instead of striking, but worse still, on the very night that Iola is giving birth, the Super forces Joe to squeal on the new union that is being organized by Hansy McCulloh. Shortly afterwards, at a picnic given by Joe to celebrate the birth of his son, it is discovered that McCulloh has been taken for a ride and beaten up by company thugs and that Joe lied about the mine not being “hot.” Just then, it is heard that a miner has been seriously hurt in an explosion. Furious that they have been sent to work in a gas laden mine, the men go out on strike. Joe denies his guilt at first, but is forced to confess by Tony. Joe tells his brother that he was driven into taking his rat job, that he turned stool-pigeon for all of them, for Tony too. The crippled miner cries out furiously.

“No! Jesus Chris’ you be lie. I no be like you. I go’n sleep on the groun’ I go’n eat coal. I go’n die from starve ‘fore I be cheat op odern miner. You wan’t be stool pigeon? You lak be stool pigeon. O.K. (He spits at Joe) I no gone stay in same howse wit’ stool pigeon…And when Joe tries to tell Tony that he did it for Iola, because she would have died without a doctor, Tony answers:

“Joe, Joe, bett’r be Iola die from baby-bett’r be you die from starve.”

Tony tells Joe to go away, the miners will never trust him again, and as his stool-pigeon brother departs, Tony wheels his cripple’s chair to the window to watch the picket line outside. Then he turns to Iola who is sobbing on the bed and says:

“Never mind…Lil fella gone grow up…he no crawn on belly to get pice bread…outside miners…by God, miners gone raise head oop in sun holler out, Jesus Chris’…miner gone blow whistle not boss blow…blow Jesus Chris’ I never gone die…I gone sit here wait for dat tahm.” (The siren screams)

THIS recounting of the story of the Black Pit gives no idea of how effectively it was brought to life on the stage. The fine acting of Martin Wolfson, as Tony, brought home its revolutionary message. George Tobias, Harold Johnsrud and Tony Ross made the boarding room scene unforgettable, and Clyde Franklin as the Super did nobly in an ignoble and rather heavily written part. Alan Baxter, as Joe Kovarsky, played the difficult role well except for that trace of a juvenile-lead quality which Brooks Atkinson pointed out justifiably in the New York Times. I wonder if the playwright, or the director, or Millicent Green was responsible for making Iola so cloyingly sweet?

The direction by Irving Gordon showed a real advance over that of Sailors of Cattaro. The handling of the scenes between Joe and the Super were excellent, but I was disappointed in the card-game strike meeting and the picnic scene. Here was a chance to play a rich script for all it was worth, to break completely with the sombre, depressing tone of the play and thus to intensify the ensuing tragedy.

The lighting in the prologue, with the spot encircling Joe, Iola and the minister, while the law stood back in the shadows (all this in a tiny room), made the scene look like a posed Hollywood close-up. Most of Tom Adrian Arcraft’s sets were effective, however, and one, the exterior of Joe’s house at night, was so fine that the it brought spontaneous applause from audience.

I believe that Albert Maltz missed two real opportunities to make his Black Pit an even finer play, and both result from his failure to give a proportionate representation to the lives of other miners besides Joe and Tony. If, instead of the tragic first scene, the playwright had shown the miners throwing a party for Joe’s welcome home from prison, the betrayal of these men later would have been even more terrible. It is difficult to feel genuine sympathy over the reported deaths of characters whom we know only by name. Also, apart from our natural desire to see the miners at work sometime during the course of the play, the accident resulting from Joe’s lies would have been far more dramatic if it had been staged instead of talked about.

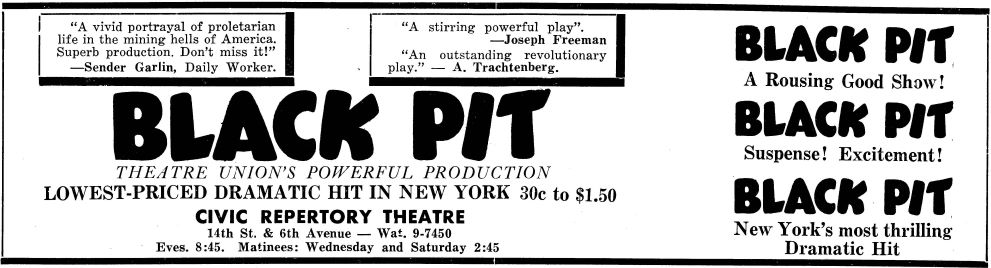

Perhaps it is unfair to deal primarily with these few faults of The Black Pit. Its accomplishments are so high in quality of writing, in rich characterization, in sustained emotional intensity that I urge every reader of NEW THEATRE not to miss this significant revolutionary tragedy.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n04-apr-1935-New-Theatre-UCB.pdf