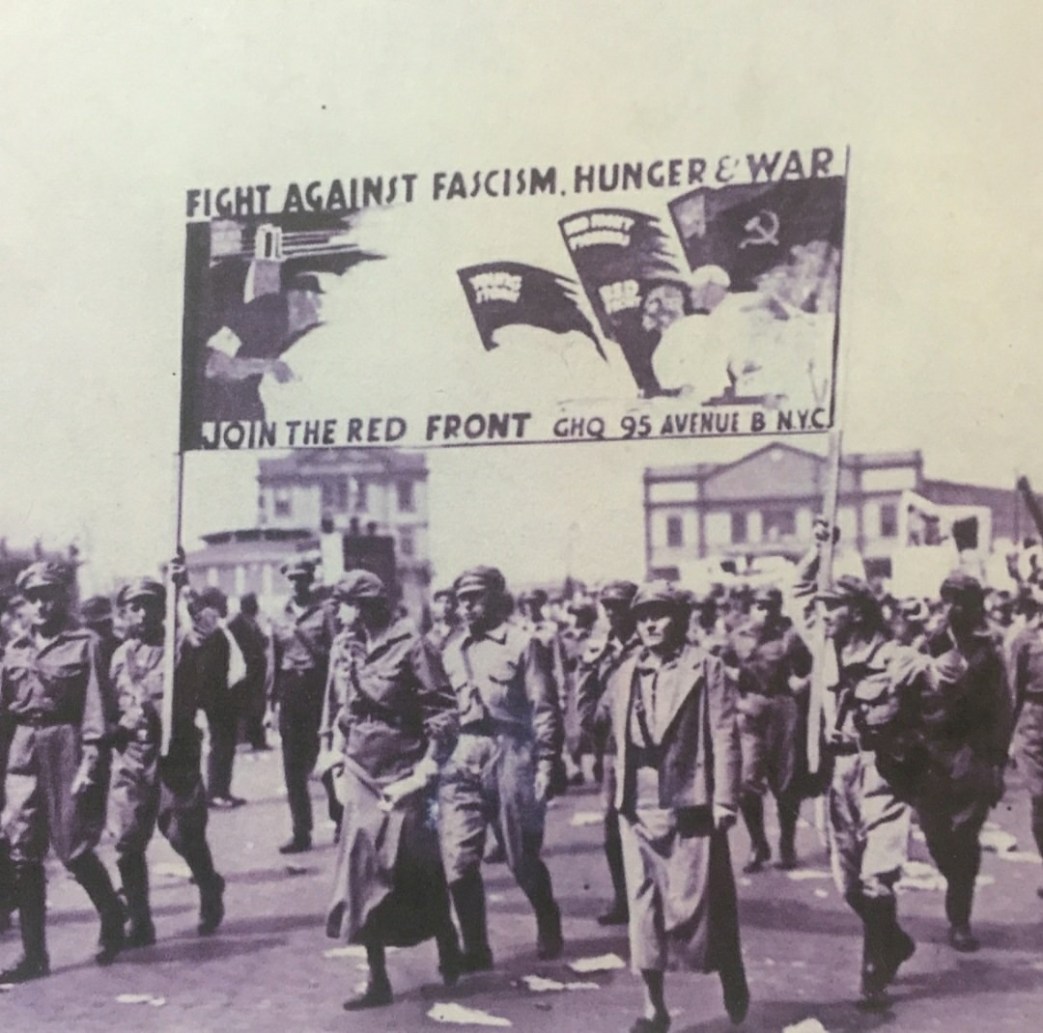

While not a constant, physical fighting in the streets between revolution and reaction is an absolute inevitability of the class struggle, especially as political conflict is heightened. Here, a ‘Third Period’-era look at how it was done in the early 30s, its organization and methods.

‘The Fight for the Streets’ L. Alfred from Communist International. Vol. 8 No. 15. September 1, 1931.

AMONG the forms of revolutionary mass struggle at the present time, street demonstrations are of particular importance. Spontaneous unemployed demonstrations, hunger marches, demonstrations in connection with strikes, joint fighting demonstrations of industrial workers and the unemployed are on the order of the day. In spite of the prohibition of demonstrations, in spite of emergency decrees against “political excesses,” in spite of the steps taken by the bourgeoisie: to hold in readiness and even to set in motion their fighting forces, equipped with tear gas bombs, rubber batons and “harder weapons,” as if for civil war, the masses continue more and more boldly to come on to the streets to express their indignation against capitalist economic failure, against hunger, want and misery, not only in the towns but also in the countryside. More and more boldly they are engaging in battles with the armed guards of the bourgeoisie.

Not only is this the case in Germany and Poland, where collisions between the militant masses and the armed forces of the bourgeoisie are an everyday occurrence, but also in countries such as Sweden and Norway, which until a short time ago were regarded by many as the wonderlands of perpetual class peace. Communists must pay very close attention to these events. Investigations into the size of the masses which have taken part in these struggles, into their composition, whether they were composed of the conscious, organised revolutionary advance guard or whether the demonstrations consist of sections which have hitherto not taken part in struggles, whether they are industrial workers or unemployed, what determination they showed in the fight, what was the strength of their opposition to the police—such investigations yield the most valuable and reliable material for judging the general position of the class struggle and the stage which the crisis has reached. But the duties of Communists in connection with the fighting demonstrations of the present day cannot be limited to such investigations. These demonstrations must not only be investigated, but in particular must be given practical guidance and leadership. The worst thing that can happen to a Communist is for him only to look on at the fight of the masses and not to fight actively with them. The question of demonstrations is a burning organisational problem of the present day, a question of technique. The use of an elastic tactical method by the revolutionary masses in demonstrations is urgently demanded by the class struggle as it is developing today.

The creative initiative of the masses in their fight for the streets is constantly bringing new experiences, new forms of struggle. It is in the course of these struggles that the correct tactics for demonstrations will be worked out, and Communists must learn them in order to be able to lead the masses who are fighting on the streets. It is only on the basis of a careful study of these recent experiences of struggle that any fruitful discussion of the question of tactics for demonstrations becomes possible.

The necessity of regarding demonstrations at the present time as an art, and of making use of an elastic, mobile tactical method free from, any tendency to become stereotyped, has been forced on the workers by their class enemies, When demonstrations are prohibited and therefore have to be carried on illegally, when the bourgeoisie mobilise their guards equipped for civil war against the demonstrators, when demonstrations have to be carried out under the constant menace of attack by police and Fascist murder-troops, then it becomes clear that they must be organised in quite a different way from the more or less peaceful political processions of the preceding years of capitalist stabilisation. It is absolutely necessary to cast aside the usages, traditions and methods of these old demonstrations, because to stick to them under present conditions entails a bloody punishment.

The bourgeoisie now fights the revolutionary fighting demonstrations of the workers and peasants with methods of civil war. In the fight with the demonstrators, the bourgeoisie acts on the principles of the same tactics as it employs for the suppression of an armed revolt. It uses the fight against demonstrations as maneuvers in preparation for civil war, so as to give its State apparatus and its Fascist and Social Fascist “volunteer” murderers practice in waging civil war. But in doing this it compels the workers, who meet with open provocation and attack, to undertake corresponding defensive measures; it makes it necessary for them to answer each new maneuver of their armed guards with a corresponding counter-maneuver, to meet the bourgeois tactics in suppressing demonstrations with correct tactics in the carrying out of demonstrations. Through using the methods of civil war the bourgeoisie only succeeds in making the demonstrations into a kind of maneuvers in preparation for civil war on the side of the workers also, in enabling the workers to gain during these struggles experiences which are of value from the standpoint of the decisive struggle.

How impossible it is to use old methods in the fighting demonstrations of the present day was shown by the experience of the failure of the antifascist demonstration in Helsingfors on the occasion of the Fascist “march on Helsingfors” on July rst of last year. A critical analysis of this demonstration was given in the “Proletaari,” the organ of the Finnish Communist Party. The Lappo group and other active Fascist elements from the whole country gathered in Helsingfors on July 1st and held a great demonstration on the central square of the town, the so-called Senate Place. The local Communist leadership did not know any better than to try to meet this situation by summoning the workers of Helsingfors, by means of leaflets, to a counter-demonstration at the same time and place. But the workers, who up to then had followed the calls made by the Party, did not turn up on this occasion. There was no counter-demonstration. The Fascists were able to carry on with their insolent counterrevolutionary demonstration without any interference.

The fact that at the time of the Fascist revolution the spirit of the masses was low is not in itself enough to explain the complete failure of the counter-measures against the Fascist coup. The fact that the Communist Party did not succeed in bringing the masses on to the streets is to be ascribed largely to its own passivity and helplessness. The complete failure to understand how a mass demonstration must be organised under present conditions was only an expression of that helplessness.

It was, of course, correct to summon the masses to a counter-demonstration, but everything else that was done was wrong. The whole of the preparations made for the demonstration consisted only in the distribution of a leaflet. That was how they had always done it before, and it had always come off. But the distribution of a leaflet is inadequate as a means of organising an illegal mass demonstration, It was a particularly gross blunder to suppose that without any preparation whatever the workers would assemble on the Senate Place, where the most active and bloodthirsty sections of the Fascists from all over the country were concentrated, armed with long knives and revolvers and ready to fight, and where the police had gathered the whole of its forces. Such an assumption was all the more naivé because the leaflet “honestly” gave the place of the illegal demonstration. It is not to be wondered at that the workers did not follow this advice, that they did not go one by one into the enemy’s camp without first assembling and organising their forces.

Just because of the fact that, as a result of the white terror and the deviations among the Communists, the spirit of the workers was low, the organisers of the demonstration should have set themselves, in the first instance, a much more modest task than a direct frontal attack on the heavily-armed main forces of the enemy. They should have raised the self-confidence of the masses, they should have shown them that a mass struggle under difficult conditions can be carried out, provided that the correct approach is made, provided that the first thing that is undertaken is a relatively easy tack, and then, encouraged by minor successes, it is possible to pass on to the solution of the more difficult tasks of the struggle. The following out of this line would have meant, in connection with the “march on Helsingfors,” that the first task to be undertaken was real preparatory work in the factories and working class districts, then the assembling of the workers in the working-class districts, and only then the attempt to push forward into the centre of the town if the strength and spirit of the masses had been such as to justify this bold step.

The points at which demonstrations first assemble, and from which they march off, must be where the working masses are, where they can be most easily attracted, where the opponents are weakest: in the factories, at the exchanges, in working-class districts. This rule is simple and cannot be disputed, and yet it is often forgotten. It is true that successes have been achieved with surprise demonstrations in the centre of towns, where the demonstrators have assembled in small numbers in the streets near the centre, and then suddenly formed a demonstration under the eyes of the astonished police and the “upper classes.” But even such demonstrations are as a rule first prepared in the working-class districts.

Although the working-class districts must be the points from which the demonstrations must move off, this does not by any means imply that demonstrations should limit themselves to the working-class districts. On the contrary, demonstrations in working-class districts are as a rule only justified when the forces are too weak to penetrate the middle-class areas. Demonstrations must start in the working-class quarters in order to bring on to the streets the largest possible number of workers and then to move forward to the real objective of the fight, which generally lies in a non-proletarian quarter. The fighting demonstration of today is not a political procession, but a real means of exerting revolutionary mass pressure. In recent demonstrations the special objectives of the struggle have been town halls and other public buildings. The objectives of the struggle, of course, vary as the political situation changes. But in any case it is right and proper that proletarian demonstrations should tend to be directed towards middleclass areas. A great hunger march from the districts of the poor to the districts of the rich is in one of the most successful forms of fighting demonstrations at the present time.

It is true that the police do not like the starting points of demonstrations to be in working-class districts, especially if the demonstrators assemble not at one place but at several points, because this compels them to split up their forces and to maintain an extensive service of patrols as well as to decentralise the police reserves. The fundamental principle of the police tactics in suppressing “internal disorders” is the concentration of forces, the avoidance of splitting up the police forces and thus allowing them to be beaten piecemeal. For that reason there can be no more advantageous position for the police, enabling them to attack the demonstrators, than when the masses are called to one central assembling point or a small number of points, as was done in Helsingfors.

The decentralised, “partisan” method of assembly for a demonstration has the further merit of surprising the enemy; there are many possibilities of misleading the police. Of course, a mass demonstration which is not spontaneous but is the result of preparation cannot come as an absolute surprise to the police, because the arrangements and the time of the demonstration must be made known to the largest possible number of workers. But it is not absolutely inevitable that the police should know at what points large contingents are to meet and through what streets the demonstration is to pass.

Of course, the workers at various factories, exchanges, houses or blocks must know where they are to assemble in the first instance, after which they will follow the lead of groups acting under special instructions. But even if these points are known to the police it is impossible for them to post overwhelming forces at every factory, every house and every public house where ‘the demonstrators may assemble. In order to split the police forces still further, in some demonstrations recently special groups have been formed whose task is to make a determined move behind the police reserves and in this way to keep the reserves busy and draw them off, freeing the main mass of demonstrators and gaining time.

It used to be common tor a demonstration to march outside the town and to hold the actual meeting there, in some open space or place isolated from street traffic by gardens or parks. When a demonstration has been prohibited such a procedure is not correct. The isolation of the participants in an illegal demonstration from the rest of the inhabitants gives the guards of the bourgeoisie the most favourable opportunity for staging a blood-bath. Moreover, the effect of the demonstration is almost entirely. restricted to the participants themselves,

Where the workers have some experience in the organisation of illegal demonstrations, the demonstration is as a rule held at street corners where numbers of people are moving or in squares with a number of ways out which are better suited for elastic manoeuvring and the organisation of mass defence against provocative attacks made on the demonstrators.

The question of physical resistance against police and Fascists is a particularly burning one in demonstrations at the present time. To preach non-resistance to workers who have been provocatively attacked by the police and Fascists is to abandon the field of the class struggle. Proletarian defence against armed attacks by the State and volunteer murder-columns of the bourgeoisie is not only permissible, but must be consciously organised and led. But at a period when the time has not yet come for the decisive struggle for power by the working class, when there is not yet any question of armed revolt, it is necessary also to raise the issue of how far purely physical resistance should be carried, and at what cost.

In an armed revolt attack at all costs is essential. But anyone who tries to apply this rule also to physical resistance in current class battles is guilty of a sectarian interpretation of the class battle. Lenin emphasised that strikes are a “school of war” for the working class, but not the war itself. That is true also of demonstrations. A demonstration, like a strike, cannot lead to a decisive result: the bourgeoisie cannot be overthrown by a demonstration. The bourgeoisie makes the demonstrations of the present day a “school of war,” of the decisive struggle for power, not only for the police but also for the working class.

In militant demonstrations the workers and peasants are hardened. But they are not the decisive struggle. In European countries at the present time it might be possible to lead the advance guard of the working class to an attack at any price, but not the broad masses of workers themselves. Anyone who does not take account of this fact isolates himself from the masses, and will not be in a position to lead when the broad masses are prepared to fight whatever the cost. What is necessary today is not an attack at any price, but the greatest mobility, an elastic combination of attack, defence and retreat, so far as concerns physical resistance against the civil war guards of the bourgeoisie.

After the first illegal demonstrations in Germany, the workers very soon overcame the tendency to non-resistance. It was only at the beginning that the demonstrators dispersed immediately on the arrival of the police. They very soon passed on to showing resistance in cases where they had to deal with weaker police forces, and only when overwhelming police forces arrived would they disperse, only to reassemble at another point. The German workers did not adopt the line of resistance at any price, but in each particular case decided the question of how far they were to carry their resistance, in accordance with the concrete situation and the relations between the forces.

For example, the Berlin organisation of the German Communist Party cannot be reproached for not having called on the masses to offer open physical resistance, in spite of the panic shootings and provocative attacks of the police, on the occasion of the recent great meeting at the Palace of Sport, when the building was surrounded and turned into an armed camp by the concentrated forces of the police.

The question of armed demonstrations is similar to the question of physical resistance. The slogan of an armed demonstration means the same thing as the general slogan of the arming of the proletariat. To raise the slogan of an armed demonstration without any anticipation of a speedy transformation into an armed revolt, and before the pre-conditions for a successful revolt exist, is to be guilty of playing with revolution. If certain impatient elements demand the arming of demonstrators, it is necessary to look carefully to see whether there is not an attitude of panic behind the demand. The demand: Give us arms, or else we will not go on the streets—in many cases has been nothing more than an idle excuse for passivity and unwillingness to undertake revolutionary mass work. It is characteristic that these elements ask the Party for arms instead of themselves finding arms.

During the month of June of this year in many countries there were serious clashes between workers in demonstrations and the police, in the course of which the demonstrators armed themselves with stones, bricks, pick-axes, bottles, flower-pots and similar objects. Some cases also occurred where the workers disarmed individual policemen and made use of the weapons they took from them in their own defence. To “offer” to arm the workers in this way would be ridiculous. We do not object to individual proletarians arming themselves, but we raise objection to the slogan, of arming the workers as a general agitational slogan at a period which is not ripe for armed revolt.

In recent militant demonstrations, barricades have played an outstanding role. On June 10, the Hamburg workers erected barricades of ashbuckets in order to prevent the police from entering the working-class districts. On the same day the workers in Mannheim put up barricades of boards, iron bars, dust-bins, parts of lorries, etc., in a number of streets and tore up the pavement. A few days later in Roubaix it reached the stage of putting up barricades on more than one occasion. It is absolutely clear that ail these were cases of conscious defensive measures taken by workers who had been attacked. A very typical illustration of this is the following inscription on a red flag on a barricade at Roubaix: “Behind this boundary the people rule. Murderers are not allowed to pass.”

Although the barricades in these struggles were consciously defensive measures, we could not accept as correct any formulation of such a question of “principle” as: Are barricades a means of defence or are they offensive measures? If barricades are put up to prevent police from entering the workers’ districts, this is, of course, a defensive measure. But if the police forces and the police cars are hemmed in with barricades in several directions, not only with the object of preventing them from forcing their way into the working-class districts, but also to cut off their retreat, then it is very difficult to distinguish where defence ends and a fight with a positive aim begins. It is correct to say that barricades cannot decide a battle, but that they only give a measure of help either in defence or in attack.

On the question of the cadres, the initiative groups in demonstrations, we fully accept the views of “K.F.” in the April number of the journal “October.” He writes:

“The method of also forming groups within the demonstration is by far the best method of giving the whole demonstration a better stiffening, of enabling it to act in a more unified and determined way than hitherto. No new special organisation is required for this. It is quite sufficient if from every cell four to six good comrades, who are physically suitable for the purpose and know each other well, march together in the demonstration and do not allow themselves to be separated by police attacks, but always get together again, and shout appropriate slogans, making use of suitable opportunities to give short speeches. If by means of such groups we give a framework to the whole demonstration at all points, then it will be nauch easier to get the masses to stand their ground when attacked by the police and to deliver an appropriate reply to the attack.”

Initiative-groups in demonstrations therefore do not constitute any special, independent organisation, but are organs of the Party cells or of the corresponding basic units of other revolutionary mass organisations; they are directed by these organisations, and work within the limits of the organisation. No objection could be raised, of course, to these initiative groups from the various cells, for example, in a single town, being called together for joint discussions on the eve of particular important actions and being given their instructions together. This would not in the least conflict with the correct organisational and political principle that the organising and leadership of political mass activities, including mass demonstrations, must be conducted by the basic units of the Party and other revolutionary mass organisations and cannot be handed over to any independent and special “demonstration meetings.”

The above remarks do not pretend to be infallible or comprehensive. Still less do they attempt to be instructions for the organising of demonstrations, especially as they are based on extremely scanty material of the actual experiences of demonstrations. The writer’s aim is much more modest: to open a discussion on these problems. The “theses” put forward by the writer are open to discussion. But on one point there can be no dispute: Communists cannot avoid this issue; they cannot ‘‘deny’’ the militant demonstrations of the working class, because these are historical facts which the development of the class struggle has placed on the order of the day.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This The Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-8/v08-n15-sep-01-1931-CI-grn-riaz.pdf