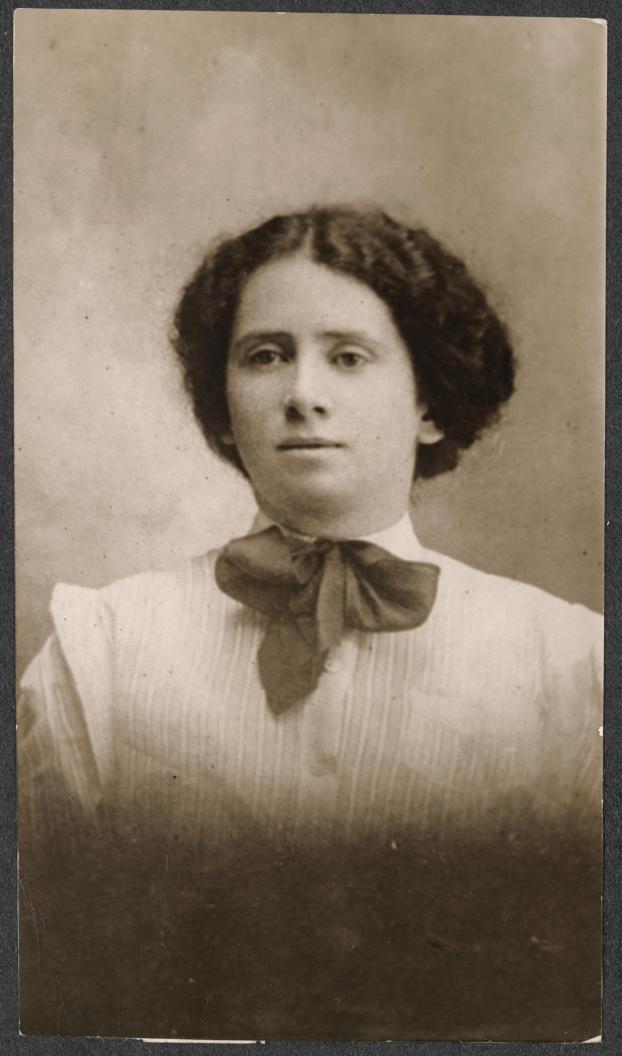

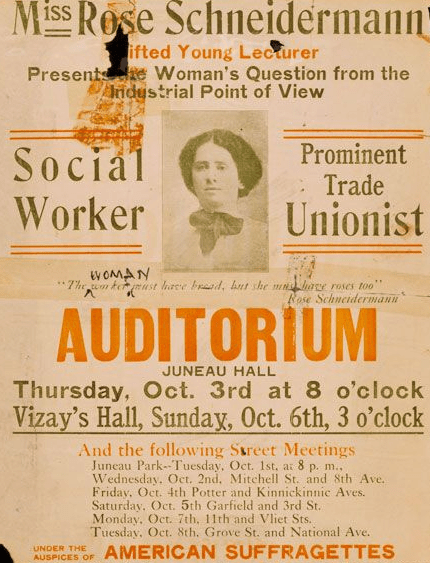

Theresa Malkiel with an early sketch of the work of Rose Schneiderman, then a Socialist activists, and the first woman elected to national office in a union. As vice president of the New York Women’s Trade Union League and she central to 1909’s Uprising of the 20,000 International Ladies Garment Workers Union strike.

‘Rose Schneiderman: A Daughter of the People’ by Theresa S. Malkiel from The Coming Nation. No. 136. April 19, 1913.

ROSE SCHNEIDERMAN was a born revolutionist, for she rebelled as early as thirteen when she had to answer the cry “Cash Here” in one of New York’s department stores. The drudgery of the girls behind the counter, the abuse heaped upon the cash girls appalled her and aroused her resentment.

She felt something must be wrong somewhere and got to thinking for herself. She compared her lot with the lot of the children of the rich and wondered why some of them were kept at school when they did not care anything about it, while she had to give up her studies and go to work, though it almost broke her heart.

But fate was after all merciful to her; what she missed in systematic study she made up in extensive reading at every opportune moment. Every incident in her day’s work was a lesson to her and helped to fill the gap in her education. Thus it happened that the unusually impressionable child absorbed life’s wisdom and stored it away in the dormant cells of her brain to be used at the proper time.

The miserable existence of her neighbors and coworkers, the uncanny surroundings, and terrible evils which were an open book to her at an early age, instead of dragging her down to their level, worked by contraries and served to develop in her a longing for justice, a taste for the beautiful, a determination to help bring about human freedom and happiness at all cost.

At sixteen she was running a foot power machine making hundreds of cap linings daily and thus supporting a widowed mother, younger sister and brother. But the conditions in the cap making industry soon aroused her wrath and at seventeen she was organizing the women in her trade into a union of which she became the organizer as well as secretary-treasurer, performing her work gratis during the hours after work.

Her activities as an officer of the local body and delegate to the central organization soon attracted the attention of organized labor, and when the Woman’s Trade Union League was first organized in the city of New York by a number of bourgeois men and women, Miss Schneiderman was the first real working woman who was asked to join their ranks.

For a while her innate class consciousness kept her from taking an active part in the work of the middle class league. She would go to their meetings, listen to the reports, then go back to her machine to think over and reason out for herself the value of the work accomplished.

In the ever increasing number of women in industry she foresaw great possibilities for the uplift of her sex and when the call finally came for her to give up her whole time to the work of organization among Jewish working women she threw herself into this work with all the enthusiasm and energy of a young idealist.

Her first experience in this line was with the dressmakers, then in the footsteps of this initiative work came busy days and sleepless nights for the conscientious organizer. The shirtmakers, necktie workers, cloak finishers, waist makers, hat trimmers, furriers, human hair goods workers, vest makers, paper box makers, laundry workers and numerous other organizations of women benefited by the guidance of Miss Schneiderman’s firm and logical mind. While her little body moved noiselessly from meeting hall to meeting hall, the kindness of her big heart won for her friends everywhere, until there was not another labor leader in greater New York who commanded the love and respect accorded to Rose Schneiderman.

During the long shirt waist makers strike of 1909 and 1910 , there was not an abler person in the whole army of speakers and leaders and at the end of the strike this fact was emphasized by the unanimous vote of the rank and file to present Miss Schneiderman with a gold watch as a token of their appreciation of her valuable services.

About this time a number of white goods workers declared a strike in one of the factories and appealed to the league for assistance. The matter was turned over to Miss Schneiderman, then organizer on the East Side. She went to work on the strike of forty girls with the same zeal as she had previously worked on the strike of 40,000 women and with the ability of a born leader, not only adjusted the differences between employer and employes, but formed the latter into a permanent organization, the first of its kind in the trade.

There was never even an attempt made to organize the white goods workers before that-the minutest division of labor had thrown this trade into the category of unskilled trades and this gave the bosses an opportunity to employ newly arrived immigrants and very young girls whom they could exploit to their heart’s content, without any fear of rebellion on the part of the workers.

The plight of the white goods makers affected Miss Schneiderman beyond all description and she resolved to better their condition, to bring them into the fold of organized labor in spite of all apparent obstacles in the way. The fact that she succeeded in organizing only forty girls out of the 8,000 in the trade did not lessen her activity. Night after night she was found in the small headquarters of the new union ever planning and devising means of gaining new members.

Then when an opportunity presented itself for increased agitation she induced the general board of the International Garment Workers Union, with whom the White Goods Workers are affiliated, to spend $500 for that purpose, get a paid organizer, permanent headquarters and the necessary literature.

She reserved for herself the right to select the man for the job, wrote the leaflets, had them printed and accompanied by the members of the union, distributed them evening after evening among the workers employed in the hundreds of shops in the trade. She held outdoor and indoor meetings, to which the workers were invited, where they were urged to join the organization.

But when the $500 were all spent and the organizer discharged for want of funds, Miss Schneiderman realized that her work failed to bring about the expected results. The officers of the general board became skeptical about the whole proposition and would no longer aid even in the maintenance of headquarters. This time the brave little woman, or the “Napoleon in the Needle Industries,” as she was often called, during the last strike, appealed for aid to the Woman’s Trade Union League. With the assistance obtained and increased membership dues she managed to keep up the headquarters, herself taking up the work formerly done by the organizer, which, with the other work of the league, compelled her to keep in perpetual motion.

While matters became rather complicated as far as financial conditions went, the rank and file kept up its steady cry for a general strike to which it looked as the only solution of its difficulties. For a whole year this general in skirts manoeuvered and promised and put them off with the true excuse-the necessity of careful preparation. Finally unable to ward off the demand any longer she placed it before the general board of the mother body, only to have it voted down unanimously.

This was like a death blow to the young organization; the few loyal members who stood by it for over two years became disheartened , accused the leaders of a compact with the bosses, and, having lost confidence even in Miss Schneiderman, stopped coming to the meetings. About the same time the league recalled her from the field. Disappointments were pouring through all doors. Criticism, too, was not wanting. Then, discouraged and almost heart broken at the failure to uplift the exploited White Goods Workers, Miss Schneiderman left the economic field temporarily and under the auspices of the Suffrage Party, toured Ohio speaking in favor of the suffrage amendment. Those who heard her and followed her activity during the few months know what telling work for suffrage and Socialism she accomplished. For Miss Schneiderman is a class-conscious Socialist, loyal party member and in her speeches never loses sight of the ultimate goal.

A pleasant surprise awaited her on her return to New York- the White Goods Workers Union had come to life again. The conditions in the trade reached a point where even the green, the stupid and the young had to rebel. The steady, persistent agitation carried on by Miss Schneiderman for over two years commenced to show results, the workers were joining their union by the hundreds.

The cry for a general strike grew louder than ever and at the first reappearance of their former leader in their midst the White Goods Workers declared emphatically that Rose must lead them to victory. A careful survey of the whole situation proved to the former that the psychological moment had arrived, the strike must be called. Armed with all the necessary facts she appeared once more before the general board of the I.G.W.U., this time with a determination, known only to those who are personally acquainted with the little woman.

“You must endorse this strike!” she told them.

“I would not take nay for an answer.” Before the meeting was over the board gave its sanction and pledged its assistance.

“But you’ll have to do the leading and also accept the consequences,” warned one of the board members. She accepted the challenge as quietly as she does most of her work.

Without much noise or further delays she called shop meetings where the girls, through a referendum vote, formally decided to call the strike. This accomplished she called a conference of radical women whom she wanted to act as supervisors over the young, inexperienced girls. Then she got in touch with a number of wealthy sympathizers whose financial aid would be needed during the struggle; organized a voluntary law committee of well known lawyers, obtained several bailers, prepared definite instructions for shop chairmen, supervisors and pickets, hired all the necessary halls to hold the 8,000 workers in the trade, made out the demands of the employes and even had blank agreements prepared for the employers to sign, sent out scouts into the uncertain shops; finally when the ground was well prepared she called her army to battle.

The eight thousand women responded as one within a few minutes after the call was issued. It must be said, much to the surprise of the general officers who did not expect this preliminary success. But their amazement was still greater when that evening during their midnight session the little general appeared before them with a number of books under her arms in which she had carefully tabulated all the girls on strike, the hundreds of factories involved, the names of those who joined the union and their shop chairmen; in a word, the whole situation under control. The experienced men took off their hats and humbly bowed before the able woman- never before was a strike situation systematized so promptly.

During the five weeks of the struggle her executive ability stood the strikers in good stead. Not much talked of in the capitalist press, unknown to many of its representatives, she was, nevertheless, the power behind the throne. From morning until late at night she moved about from hall to hall, from one conference to another, from shop meeting to picket line, from there to police headquarters; everywhere leaving signs of her good work.

Her reward she found in the victory which the girls finally gained over their employers, but not satisfied with this reward, the rank and file of the membership amplified it by electing her their president. A big field to be sure, with room for the larger woman and she the woman to fit the time.

The Coming Nation was a weekly publication by Appeal to Reason’s Julius Wayland and Fred D. Warren produced in Girard, Kansas. Edited by A.M. Simons and Charles Edward Russell, it was heavily illustrated with a decided focus on women and children. The Coming Nation was the descendant of Progressive Woman and The Socialist Woman which folded into the publication. The Socialist Woman was a monthly magazine edited by Josephine Conger-Kaneko from 1907 with this aim: “The Socialist Woman exists for the sole purpose of bringing women into touch with the Socialist idea. We intend to make this paper a forum for the discussion of problems that lie closest to women’s lives, from the Socialist standpoint”. In 1908, Conger-Kaneko and her husband Japanese socialist Kiichi Kaneko moved to Girard, Kansas home of Appeal to Reason, which would print Socialist Woman. In 1909 it was renamed The Progressive Woman, and The Coming Nation in 1913. Its contributors included Socialist Party activist Kate Richards O’Hare, Alice Stone Blackwell, Eugene V. Debs, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, and others. A treat of the journal was the For Kiddies in Socialist Homes column by Elizabeth Vincent.The Progressive Woman lasted until 1916.

PDF of full issue: https://books.google.com/books/download/The_Coming_Nation.pdf?id=j8MsAQAAMAAJ&output=pdf