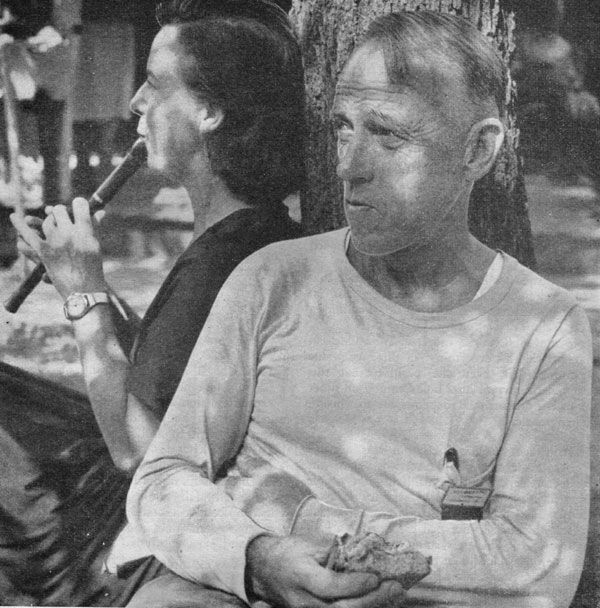

Scott Nearing was a class traitor. Born to a bourgeois family, he received his doctorate in economy from the Wharton School of Business and spent years teaching economy and sociology there and at Swarthmore College before his dismissal in 1915 for his political activity, particularly around child labor. Nearing grew increasingly radical during World War One. His old class viewing him as he was, their inveterate enemy, began a campaign against him leading to his indictment for sedition under the Espionage Act in 1918. Nearing did not bend. He became a Communist and offered his services, originating the Federated Press, a pro-worker news wire, and building workers education programs. His intense sense of political responsibility was necessarily also one of personal social responsibility. In the essay below Nearing discusses the role of the teacher and their social responsibility in society. Nearing lived until the early 1980s, and appeared as one of the witnesses in Warren Beatty’s ‘Reds.’

‘Education and the Open Mind’ by Scott Nearing from Modern Quarterly. Vol. 2 No. 4. Winter, 1925.

American teachers as a group enter the teaching profession because it pays them a living. Once inside the academic world, these breadwinners, like most other breadwinners in shoe factories and in coal mines perform their daily tasks in the habitual manner without giving them any considerable thought. The fact that class-room studies develop the mind while shoes help to cover the body makes no great difference in the teachers’ way of looking at the job that yields them a living. They teach what they are told to teach, paying little heed to the social consequences.

There are, of course, many exceptions. Thousands of teachers seek to discover the truth in their fields. They too, however, must be divided into the teachers who say what they think and the teachers who keep their thoughts to themselves.

Several class sessions may pass before a teacher is put to the test, but in the course of weeks the students, even in a large class (if discussion is permitted) can hardly avoid reaching a conclusion. They feel, almost instinctively, either that the teacher says what he thinks or else that he considers discretion to be the better part of pedagogy.

There is, to be sure, a delicate border line between thought expression and overgrown egoism, and a strong argument may be made to show that what is wanted from the teacher is not opinion, but a scientific statement of fact. According to his argument, the teacher is expected to present facts and leave the student to draw his own conclusions.

Facts constitute the ground-work of education. The teacher who presents the facts and leaves the student to sift and classify them is making it possible for the young people to do their own thinking and to build the super-structure of their own lives. The champions of this point of view ask that the teacher supply the grain and that the student do the grinding.

Several questions suggest themselves. Is not the teacher also a student, searching after truth? Must not he, like other students, work from facts to conclusions? If he leaves his task before he reaches any conclusion, has he not stopped in the middle?

But before that question is answered, another even more pressing presents itself: What are facts, and what are conclusions?

Here is an apple. Yonder is another apple. Each apple is an isolated fact. Bring them together and they make two apples. Are the two apples any less a fact than the separate single apples?

When Newton “discovered” the law of gravitation he stated a conclusion, which was based on many observed facts. But is not the law of gravitation also a fact?

The difference between a fact and a conclusion is merely this,—that the conclusion is a statement of a larger fact, a more generalized observation. All of the laws of physical and social science are statements of fact based on observation. The teacher who believes that he can state facts and refrain from stating conclusions, is merely restricting himself to the more minute experiences, and refusing to generalize that is, to make his statements cover wide experiences.

One illustration of the point will suffice. It is a fact that the miners of Illinois have raised their wages by organizing a union. It is a fact that the carpenters of New York City have raised their wages by organizing a union. It is a fact that the printers of Philadelphia have raised their wages by organizing a union. One by one these facts pile up until the student who is examining them reaches a tentative conclusion which might be stated thus: “It seems to be true that workers raise their wages through the organization of unions”. Upon further examination of the facts the student concludes that this is the case. He therefore announces his conclusion: “Workers raise their wages through the organization of unions”.

This conclusion is a larger fact, built of many smaller facts, just as a village is a fact built of many houses, also facts. The man who sees only the houses and misses the village has only a part of the truth. Each house shall be considered, but how can the village be ignored?

“But”, answers the advocate of the ‘facts only’ method of teaching, “it is not the facts which we wish to avoid, but the intrusion of personal opinion.”

Granted that this personal opinion is a prejudice, ungrounded in fact and in experience (if there is any such abstract thing) and the argument may be a sound one. There are few teachers, however, who have not some experiences upon which to base their opinions.

This is all that is expected from any teacher–a careful weighing of the evidence, and a statement of the conclusion to which the evidence gives rise. The conclusions are no less facts than the conclusions (facts) on which they are based, since the whole of knowledge is a summary of experience.

The argument for a “scientific interpretation” is quickly perverted into an argument for the facts and the facts alone. The argument for facts only very quickly reaches a point when the teacher presents what is “safe” and stops talking when “dangerous” subjects are reached. The teacher who accepts this argument is relieved from the mental labor of reaching conclusions and is also enabled to avoid risky opinions.

Life demands not only fact, but also interpretation. Without interpretation there could be no action, because, behind each action there is either a series of habitual interpretations, or else there is a new interpretation, or a combination of old ones. The life built of fact alone, without interpretation, would be as scattered as the grains of sand in an hour glass.

Indeed, the comparison fits well into the educational experience of many of those who are now going through the public school system of the United States. They are filled with a series of isolated, unrelated ideas. There is, in multitudes of the high school and college graduates, no synthetic concept–no view of the whole of life. Only the parts are known, and they exist in the mind separate and without coherence. These boys and girls are like a gang of machinists who have been given belts, bolts, gear wheels and castings, but who have no blue print of the machines they are to build.

The teacher who is confined to the statement of unrelated facts is as isolated from life as the painter who is confined to red, yellow, green, and blue, and is not permitted to mix them or blend them. Education, if it is to be of avail, must relate the child to life.

Since interpretation forms so large a part of the life of every individual, education must assist the coming generation to analyze the heritage of the past, to interpret the present, and to scan the future.

To be sure, there is the opposite extreme–propaganda. Propaganda is the presentation of selected facts and of stereotyped conclusions in such a manner as to establish a mental habit or set in a given direction. Propaganda is memory training and not education, except in so far as memory training is educational in its effects.

There is a third argument that is ordinarily raised in favor of “impartial” teaching. Not only must the teacher be scientific in his presentation at the same time that he refrains from stating his personal views or conclusions, but he must “give an impartial statement of both sides of every question”.

There may be room, in an abstract science like mathematics, for this type of intellectual self-effacement, but in the field of social science it is non-existent, because the field of social science covers various aspects of the opportunity presented to men and women to live.

Take an illustration from the realm of social history. “In the history of humanity as written,” comments Herbert Spencer, (“Principles of Ethics”, New York, 1893, Vol. ii, p. 235) “the saddest part concerns the treatment of women; and had we before us its unwritten history, we should find this part still sadder. I say the saddest part because, though there have been many things more conspicuously dreadful–cannibalism, the torturing of prisoners, the sacrificing of victims to ghosts and gods–these have been but occasional; whereas the brutal treatment of wo- men has been universal and constant”. Here is a conclusion that involves a sweeping generalization and a definite alignment of the observer. Spencer says “saddest” because he wishes to suggest wasted life and lost opportunity. Is such a conclusion justified by the facts of history? Undoubtedly it is. Then, should a teacher make it? How can he possibly avoid it?

What is the “other side” of the subjection of women? The aggressive and dominating nature of man; the pressure of biologic necessity and of economic circumstance. Do these mitigate the ferocity of woman’s exploitation or the agony of her suffering? Not a whit!

Slavery is a system of social organization under which one man says to his fellows: “You work and earn bread and I’ll eat it”. The master may hang a gold chain around the slave’s neck, feed him on delicacies and house him sumptuously, but so long as he can restrict the freedom of another against his will, he is still the master and the other is still a slave. Are there two sides to this question? Assuredly–the side of the master and the side of the slave. But modern society does not hesitate to pronounce slavery unjust, unsocial and wrong, and to make its continuance a crime.

There is not a single field of social science in which the “right” and “wrong”, the “justice” and “injustice” of a certain line of conduct do not come up for consideration. Such matters must be debated and decided by the social group because the continued existence of the group depends upon the character of the decisions that it makes.

Every teacher of social science requires some system of values with which he can measure the importance of events and of courses of action. Perhaps he may judge social activity in relation to the freedom that it affords for the development of the individual. Perhaps his judgment may be governed by the effectiveness with which the social order is perpetuated. Having adopted such a yardstick, the social scientist is in a position to measure the events which he encounters and to decide on their merits. Here are children, working in the coal-breakers of Pennsylvania and the cotton-mills of Georgia. They are denied the opportunity for play and growth; the community is grinding its seed corn; a few men and women are given ease and comfort at the cost of stunted manhood and womanhood. It is social waste. Can the teacher of social science present these facts impartially?

Again, take the industrial depressions which devastate the business world every few years, and which rack and tear the whole social life of the community. There are causes which lead up to these crises just as there are causes which lead to malaria. The teacher of hygiene does not take an impartial attitude toward the sources of misery that arise out of malaria. Shall the teacher of economics take an impartial attitude toward the sources of misery that arise out of hard times?

Difficulties and dangers surround the human race. They must be warded off and overcome. Opportunities lie all about for a fuller, richer human life. They must be seized and utilized. The overcoming of danger is one aspect of life. The utilization of opportunity is another.

The teacher who is an interpreter of truth must throw the weight of his authority in both directions. The teacher of social science, who, knowing the economic and social facts, fails to speak out, is aligning himself with the wrongs about which he has learned. His silence is an equivalent to an approval of the world in which he studies.

The issue is fundamental.

Either the teacher is a hireling of the established order, who is receiving a fee to act as its apologist and champion, or else the teacher is a servant of the community and as such is bound to take whatever stand the exigencies of his position demand.

Let us suppose that a teacher of chemistry discovers, in the course of his researches, that food adulteration is being practiced in a certain packing house. If he is an apologist for the present order he will keep silent. He may go even farther, and work out a cheaper method for the packers to use in their work of adulteration. If, however, he is responsible to the community for the administration of his office, then he dare not sleep, after making such a discovery, until he has done something to remove the danger to community health.

The meal-ticket teacher may easily rest content with the former of the two lines of conduct. Why should he worry himself even if the whole city is poisoned, so long as it does not touch his family and his friends? Beside, if he says anything, his meal-ticket may be taken away; thus the very reason for his teaching would be destroyed.

The teacher who is teaching from his love for a subject, however, and particularly the teacher who is animated by a love for his fellow-man, can scarcely justify any line of conduct short of a willingness to assume the responsibility for seeing that the menace to public health is abated. If the teacher has a standard of professional ethics, it can scarcely descend to a lower minimum.

Looked at from this angle, the teacher is a sentry–an outpost of civilization. He is trained by the community and retained by it to protect the common interest. If he is a teacher of an abstract subject, like mathematics, his duties in this direction are light. But if he elects to enter the field of a concrete study like physiological chemistry, public health, corporation accounting, or sociology, he takes upon himself all of the social responsibility implied in these studies. Having entered such a field, he can no more desert his post in the face of danger or opposition than can a sentry in the face of the enemy.

The masses of men are always face to face with enemies–begirt with foes. There are, first of all, the forces of nature–wind, flood, fire, bacteria–that endanger health and life. Then there are the greedy, the exploiters and the insensate self-seekers who are ever on the lookout for a chance to wring more profit or power from their fellows. Added to these dangers, there are the innumerable possibilities of disaster that linger along the line of every social experiment. The western world is just passing through such a period of chaos which has cost the lives of tens of millions, which has taken an indescribable toll of misery and suffering, and which involved the expenditure of enough wealth and energy to feed, clothe and house every member of the human race for a decade. Must these things be, or is it possible for scientists, working in their various fields, to discover the germs of war and to destroy them as the germs of yellow fever were wiped out of Havana or of the Panama Canal Zone?

The answer rests with the students and teachers of social science, just as the answer for yellow fever rested with the students and teachers of public health.

The public health expert regards himself as the guardian of the health of the community that employs him. When the challenge came to combat yellow fever, these men and women entered the arena, girded for the struggle. Some of them lost their health. Some even lost their lives, but in the end they won.

The teachers of social and allied sciences face the same challenge at the present moment. The world finds itself in a desperate situation–facing famine, disease, the possibility of additional wars which may wipe out whole communities. The challenge is as unmistakable in this case as it was in the matter of yellow fever.

The teacher is a sentry–an outpost in the realm of ideas. Most men and women are too busy with the routine of industry to devote themselves to the solution of these problems. They leave the task of handling ideas to teachers, editors, preachers. These last are therefore bound in a double sense–by the character of their calling and by the trust that the masses of men place in their judgment and their conclusions.

If the students and teachers of history, economics, sociology and kindred topics do not see the dangers which threaten the common man, he will never become aware of their presence until they leap upon him. And if the social outposts do not warn him in time, how can he prepare to ward off the impending disasters?

Does the lookout in the foretop leave his post? Does the sentry sleep on his beat? Can the teacher be faithless to the trust that has been committed to him by society?

Silence and desertion are the same thing in the teacher. The lookout who sees a rock and does not warn the helmsman is a traitor to his ship. The sentry who hears the enemy approaching and makes no outcry is a traitor to his comrades. The teacher who sees danger approaching the community and remains silent is a traitor to his science and to his constituency.

Nay, but it is possible to go even further and to say that just as it is the duty of the lookout and of the sentry to spy out danger, so it is the duty of the teacher to spy out danger, and for the same reasons.

The abysmal silence which is maintained by so many of the American teachers is due to two main causes. The first is their ignorance. They do not see that there is anything to be done. Such teachers are clearly incompetent and should be replaced.

Again, there are those teachers who do not speak out because they are afraid of the consequences. They lack courage or they are tied up by financial or social bonds. They should never have become teachers.

The teacher, like the preacher and the editor, is a custodian of a great social trust. His fellows depend upon him to seek out the hidden meanings and to reveal the underlying forces. The teacher is a member of that group of professional people whose business it is to see that ideas are clarified, understood, and transmitted from one generation to the next.

The teacher dare not be false to his trust. He may not care to face the music of public criticism and public ostracism. He should then leave the job of teaching and sell life insurance or lay bricks or stitch coats. But if he remains in the profession there is but one honorable thing for him to do, and that is to seek out the truth, to proclaim it, and to seek to build it into the life of the community that places its trust in him.

The teacher who enters the profession for a meal-ticket is a time-server, and is not worthy the name of teacher. The teacher who enters the profession and remains ignorant of his subject is incompetent. The teacher who understands the dangers that threaten and who does not speak is an intellectual prostitute, selling himself and his abilities at the same time that he betrays the trust that the community has placed in him. The soldier who betrays his command may endanger a whole army. The teacher who betrays his intellectual trust may endanger an entire community.

Most of the American teachers are in the business because it pays them a living. Most of them are ignorant of the larger world that lies immediately about the homely events that clutter their own door-steps. Most of them neither know nor think about the greater issues upon whose outcome depends so much of the future. Therefore, they escape with the titles “time-server” and “ignoramus”. No more blame attaches to them than to the child who is burned on a hot kettle-lid or who plays with matches under his bed. It is the community that is responsible–responsible for their education and the home training to which they have been subject; responsible for allowing them to begin teaching at seventeen or eighteen or nineteen or twenty; responsible for permitting them to remain in their surroundings of mental incompetence. These teachers are like the sheep wandering the hills without a shepherd, and without knowledge of the precipices that yawn on either side.

But there are teachers, and not a few in number, who, with a full knowledge of the dangers that lie about, continue, with their tongues in their cheeks, to take a salary and to perform their part in raising up another generation of ignoramuses which, in its turn, shall complete the round of ignorance and prejudice, and pass it on to the next generation. For such teachers there is no language strong enough-no condemnation sufficiently severe.

The masses of American teachers are merely selling their birth-right for a mess of pottage. The members of the intelligent minority are betraying the community that they profess to serve.

Each strike, each gag-law, each red raid, each act of imperial aggression, each threat of war offers the teacher of the country a new opportunity to take a stand. They may choose to sit silent or they may decide that their duty to themselves and to the future compels them to speak. Thus far, the overwhelming majority of American teachers have chosen silence, and by that choice have aligned themselves with the established order.

Modern Quarterly began in 1923 by V. F. Calverton. Calverton, born George Goetz (1900–1940), a radical writer, literary critic and publisher. Based in Baltimore, Modern Quarterly was an unaligned socialist discussion magazine, and dominated by its editor. Calverton’s interest in and support for Black liberation opened the pages of MQ to a host of the most important Black writers and debates of the 1920s and 30s, enough to make it an important historic US left journal. In addition, MQ covered sexual topics rarely openly discussed as well as the arts and literature, and had considerable attention from left intellectuals in the 1920s and early 1930s. From 1933 until Calverton’s early death from alcoholism in 1940 Modern Quarterly continued as The Modern Monthly. Increasingly involved in bitter polemics with the Communist Party-aligned writers, Modern Monthly became more overtly ‘Anti-Stalinist’ in the mid-1930s Calverton, very much an iconoclast and often accused of dilettantism, also opposed entry into World War Two which put him and his journal at odds with much of left and progressive thinking of the later 1930s, further leading to the journal’s isolation.

PDF of full issue: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112001580031