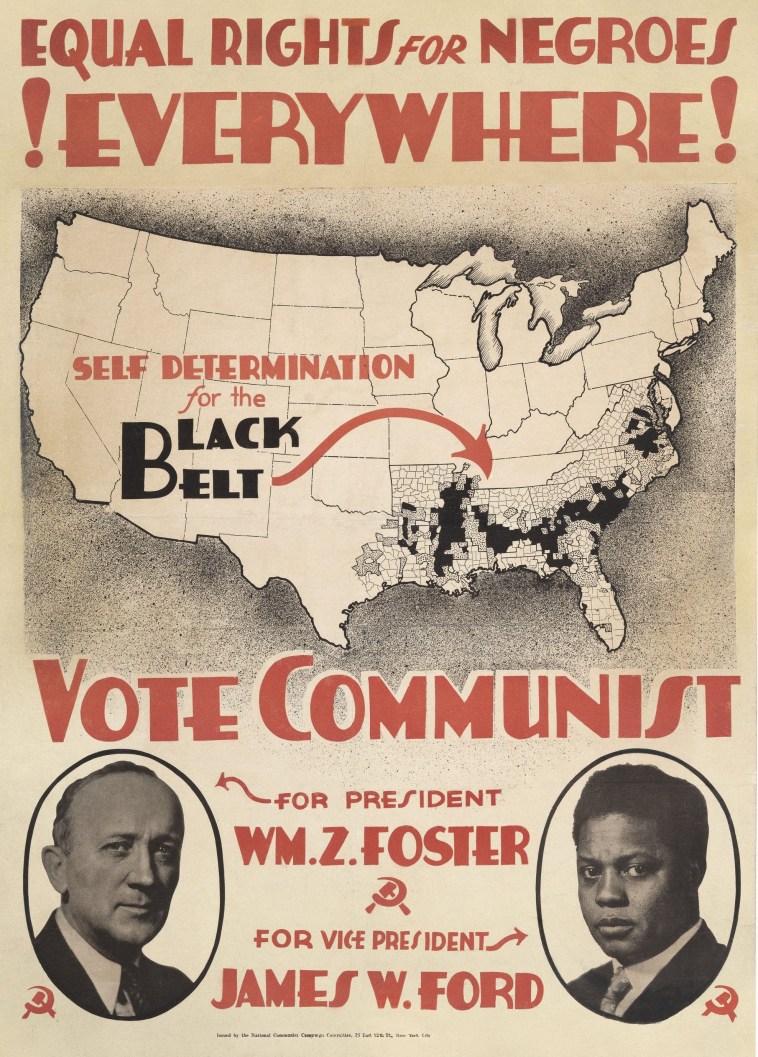

An important document in the history of the Communist Party”s evolving orientation towards Black liberation. One of the architects of the ‘Black Belt’ national self-determination position adopted in the early 1930s was James S. Allen. Allen wrote this explanation and defense for the Party’s theoretical journal as part of what would become a larger work.

‘The Black Belt: Area of Negro Majority’ by James S. Allen from The Communist. Vol. 13 No. 6. June, 1934.

(This is a section from a larger work on the Negro question. As such, it is part of a broader treatment of the subject, and the reader should not expect to find all questions raised here answered in this excerpt.)

THE existence in the South of a continuous and well-defined area where the Negroes have formed the majority of the population practically from the time of the first settlement of this territory is fundamental to both an analysis and a solution of the Negro question in the United States. In a study of the factors which led to the formation of this area and particularly of the factors which prolonged its existence after the overthrow of chattel slavery, is to be found the basic data defining the present situation of the American Negroes.

Bourgeois population and agricultural studies have recognized the existence in the South of a large area in which the Negro population is concentrated and which has come to be designated in a general way as the Black Belt. A conjuncture between cotton culture, plantation economy and areas of Negro majority has been noted in these studies. In various historical surveys the old slave economy is compared with the present-day cotton plantation. It has long been a commonplace in northern liberal literature, even to be found today in the writings of the southern liberals of the “new school”, that there exists in the South a species of bondage not far removed from chattel slavery. Economically, socially and politically the area variously dubbed as the “backward South,” the “cotton belt,” the “bible belt,” and the “solid South,” has been vaguely recognized as unique with respect to the rest of the United States. In short, the bourgeois social sciences have at most only been able to perceive isolated phenomena without grasping their profound implications when placed in proper relation to the whole complex of capitalist society.

The Census Bureau of the United States has made special studies of this area, based on its decennial enumeration of population by county and color. According to the 1930 Census of Population there are 192 counties in the South in which Negroes constitute half or more than half of the population. The number of such counties has decreased since 1860 when there were 244 counties in which half or more than half of the population was Negro. Only in the state of Mississippi were the Negroes in the majority in 1930, The counties of Negro majority are grouped in southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina, in a continuous belt of territory stretching from the South Carolina coast through central Georgia and Alabama and into Mississippi, and in another slightly detached area embracing the lower Mississippi River valley. Although the number of counties having clear Negro majorities has decreased, the contours of the area in which they are situated have undergone little change since 1860.

Critics of the Communist analysis of the Negro question have most frequently based their counter-argument on the assertion that this analysis is but a mechanical application of a policy perhaps appropriate elsewhere, but having no reality in the United States for the simple reason that there is no contiguous territory of Negro majority in the country, and that even if such a territory exists, it is so small and disconnected and contains such a slight proportion of the total Negro population of the country as to offer no basis for the application of the right of self-determination. For example, Norman Thomas, spokesman of the Socialist Party, basing himself on a very superficial glance at census figures, such as outlined above, declares that there are only spots of Negro majority and that therefore the Communists have no basis for their contentions. He charges the Communists with advocating a number of jim-crow Negro republics in the South, intensifying race hatred and propagating “race war”.1 In the same strain, it has been pointed out that the mass migration of Negroes from the South during and after the World War, coupled with the effects of industrialization in the South, has destroyed any claim, perhaps justified previously, to the continued existence of the Black Belt. With Mr. Thomas’ political deductions, as well as those of other pseudo-Marxists who follow the same line of reasoning, we shall deal later. At the present we are concerned with establishing the existence of the Black Belt as an area of continuous Negro majority, a fact which can be proved by statistical data.

The problem, however, is not as simple as it might seem at first glance. At most, the census data given above only presents the densest area of Negro population and indicates the core of the Black Belt. A further examination of population figures shows that there are 285 counties, grouped around the counties of clear Negro majority, in which the Negroes constitute between 30 per cent and 50 per cent of the population of each county taken singly. In this more or less continuous stretch, comprising 477 counties, there are 13,744,424 inhabitants, of which 6,163,328 are Negroes, forming 44.8 per cent of the total population in 1930.

A mechanical addition of county population figures, without any regard to the factors which determine this concentration of Negro population, is in itself insufficient. However, from the point of view of population, these figures do indicate the contours of the Black Belt. But even within these limits the figures given above do not sufficiently define the area of continuous Negro majority. In the first place, they are based upon percentages of population within each county taken singly. Populations do not stop short at county or state lines. Because a county line, cutting through a specific area, happens to separate on one side of the line an area in which, say, 60 per cent of the inhabitants are Negroes, and on the other side an area in which only 35 per cent are Negroes, is no reason to drop the 35 per cent area from the whole territory of Negro majority. County borders serve political and administrative purposes, and they have been changed at will to meet the needs of this or that political party. This is especially true in the Black Belt, where reaction set itself the purpose of destroying the political power of the Negro masses and disfranchising them after the defeat of post-Civil War reconstruction. In the second place, the figures given above merely indicate that somewhere within the territory in which the 477 counties are situated there does exist an area of continuous Negro majority.

In order to determine the specific region of continuous Negro majority it has been necessary to retabulate the available census data on population in the South without regard to existing state or county borders, although we are limited by the census to considering population in county units.

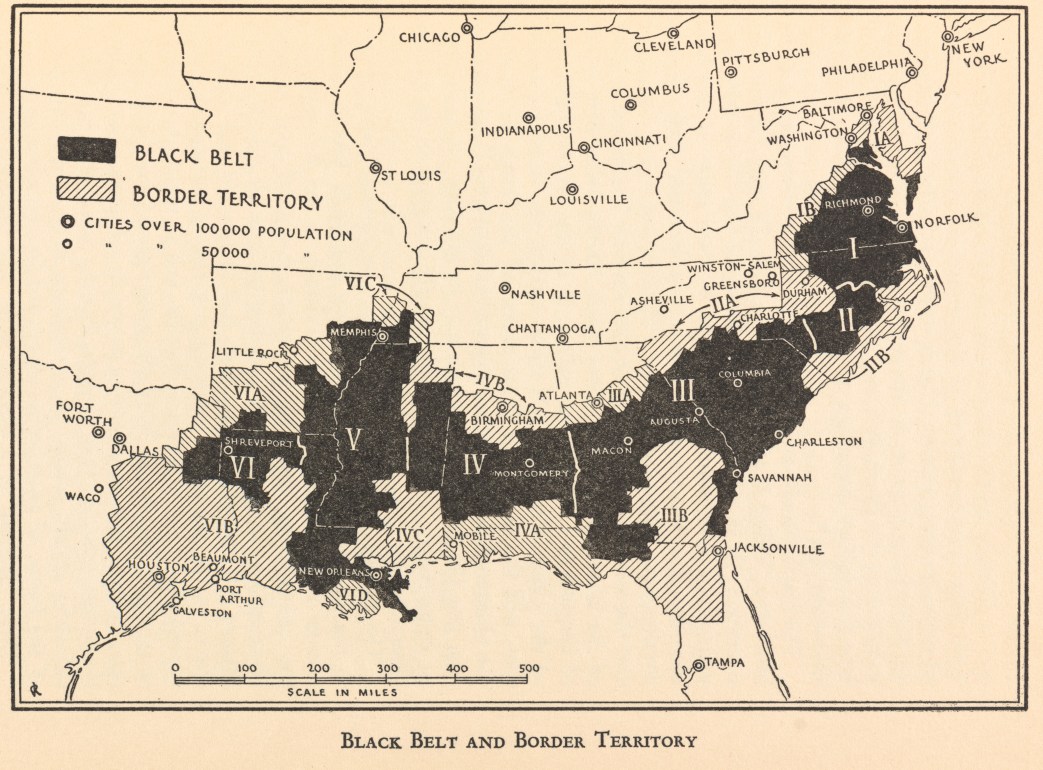

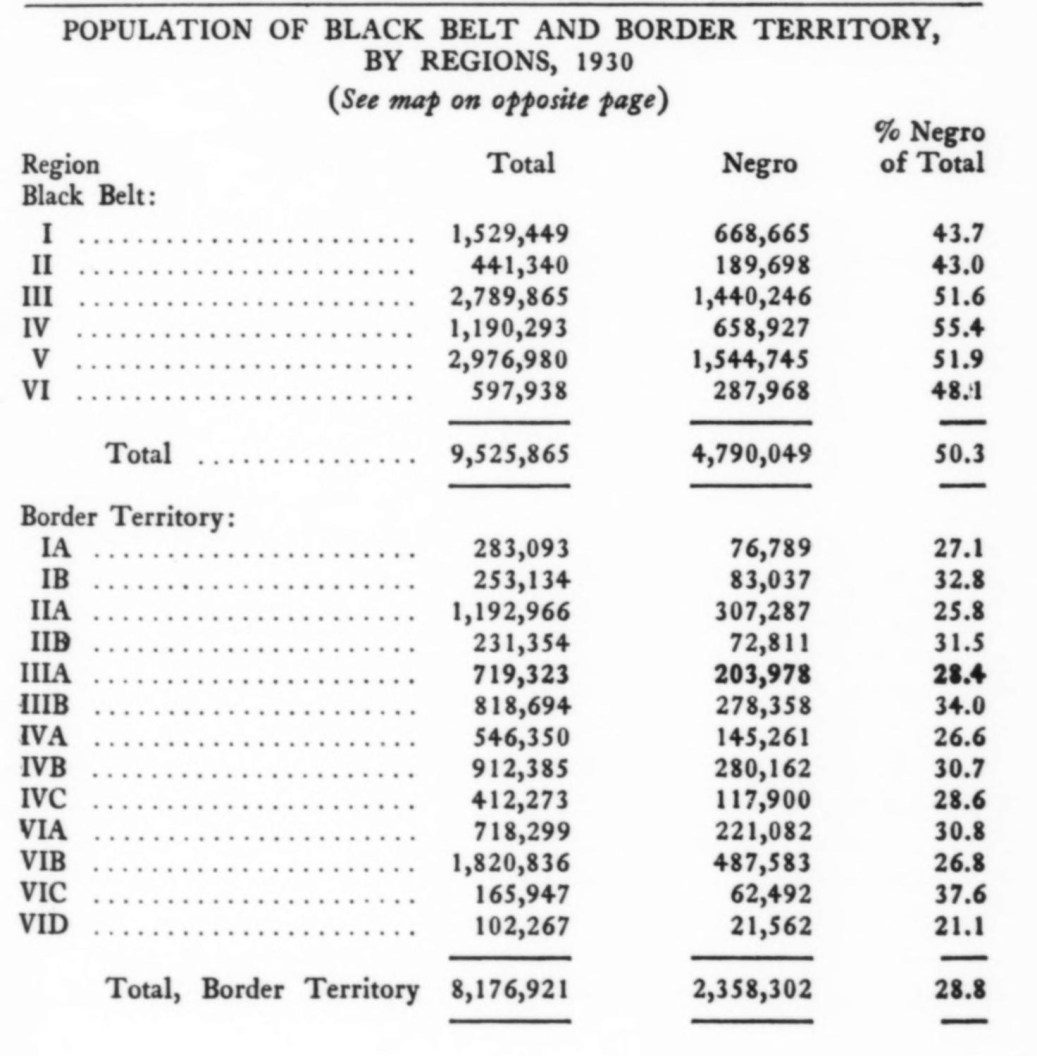

This area is shown in the map on page 586. The solid portion of the map shows the continuous territory in which the Negroes are just slightly more than half (50.3 per cent) of the total population. In determining this area the counties of clear Negro majority have been used as a basis for a broader and continuous area, within which are to be found isolated counties or groups of counties which do not have Negro majorities. There are 9,525,865 inhabitants in this territory, of whom 4,790,049 are Negroes. Of the total Negro population in the United States, 40.3 per cent live here.

Needless to say, neither the composition of the population nor economic and social conditions alter suddenly at the borders of this territory. There is a gradual decrease in the density of the Negro population as well as a gradual change in economy along its periphery, A study of the periphery of the territory of Negro majority should throw additional light upon the latter and we have indicated the limits of this borderland on the map. In the periphery there is a population of 8,176,921, of which 2,358,302 are Negroes, constituting 28.8 per cent of the inhabitants, and 19.8 per cent of the total Negro population in the United States. The area of continuous Negro majority we shall call Black Belt, its periphery will be termed Border Territory. The distribution of the Negro population in 1930 is summed up in the following table:

In analyzing the distribution of the Negro population in this manner it is not our intention to imply that immutable and unalterable geographic limits exist, corresponding to what we have termed Black Belt and Border Territory. To a certain degree, the limits we have set for these territories are more or less arbitrary and have not been defined by us on the basis of population statistics alone. In the case of the Black Belt, population data was the principal basis for determining its contours. But other factors also had to be considered, of which the most important is the extent of the plantation economy which is the most powerful factor determining the area of Negro majority. Certain areas which, taken singly, have not a clear Negro majority today have been included in the Black Belt precisely because of the persistence of plantation economy, although in a deteriorated state, and because chattel slavery has left its imprint there to the present day. Since the Negro is the principal victim of the plantation, its extent is reflected in the proportion of Negroes in the population. Thus, in those southern areas where there is the greatest proportion of Negroes the plantation system is the strongest.

In the case of the Border Territory, a fringe was simply set off depending in extent principally upon the percentage of Negroes. In some cases this area has been enlarged because of the specific problems raised by its peculiarities of location or economy, in other cases because at one time it had a clear Negro majority. This territory offers an especially valuable basis for comparison with conditions in the Black Belt, particularly in analyzing the special characteristics of capitalist development in the South.

Here a distinction must also be drawn between a method employed to facilitate the analysis of the Negro question and its practical solution. It is true that in determining the extent of the area of continuous Negro majority and of the Border Territory, we have also kept in mind the practical solution of the Negro question as encompassed in the application of the right of self-determination for the Negro people. But the Black Belt, understood as the area of continuous Negro majority, does not set the limits of a future autonomous republic in a Soviet America. Whether such an autonomous republic is to be formed, how large it will be, cannot be determined by merely calculating percentages of population. Other factors, such as its historical development, its economy, its relation to the United States, the states of the revolution there, etc., are equally important. In any case, whether Negroes living in the area outnumber the whites, or whether they form only 49.9 per cent or 45 per cent of the population is not the determining factor, either from the point of view of defining the nature of the Negro question or for purposes of establishing an autonomous republic. Such a republic, it is highly probable, might include both the Black Belt and Border Territory in which the Negroes are 40 per cent of the total population, or with some variations.

However, the final solution of the Negro question under Socialism must also depend upon the development and the course of the struggle for Negro liberation. It has been chiefly to show the roots of the Negro question and more succinctly to demonstrate its connections with the economic slave remnants in the form of the plantation, that we have made such distinctions as to territory. By defining the territory in which the Negroes just outnumbered the whites in 1930 (we might have take as a basis for our study a larger area in which the Negroes form the majority of the population in 1900 or 1910) we have at the same time indicated that area upon which the antagonisms of capitalism in the United States have been greatly intensified by the remnants of slavery and the most severe subjection of the Negro masses. And it is here, therefore, that powerful revolutionary forces are also accumulating.

The Black Belt and the Border Territory have not been subject uniformly to the economy of chattel slavery, to the post-Civil War transformation of the plantation and to the forces of capitalist development. This is necessarily reflected in the proportion of the Negroes in the population. In order to facilitate comparison the Black Belt and its periphery have been divided into sub-regions according to certain historical and economic characteristics (see table below). The South Carolina-Georgia, the Alabama-Mississippi and the Mississippi Valley Black Belt regions (III, IV and V on the map) together contain 77 per cent of all the Negroes living in the Black Belt proper. ‘The present-day plantations are situated in these areas. It was here also that the chattel slave plantations attained their highest development. The northernmost (Virginia and North Carolina) and the western (eastern Texas and western Louisiana) regions of the Black Belt, which together contain 23 per cent of the Negro population of the Black Belt, show the lowest proportion of Negroes in their populations.

The largest Negro populations in the Border Territory are in the rice plantation area adjoining the Black Belt in southeastern Texas and southwestern Louisiana, in the Arkansas cotton country, in the Alabama heavy industrial area around Birmingham, in the cotton growing sections of the Piedmont Plateau not included in the Black Belt in Georgia and the Carolinas, and in the tobacco, turpentine and timber sections of south central Georgia and northern Florida. With the exception of the Birmingham area, large Negro populations occur in plantation or former plantation areas, or, as in Georgia and Florida, where industries closely related to agriculture have taken over some of the forms of exploitation developed by the plantation.

Seventy years after the abolition of chattel slavery the area of the old slave as well as the modern peon plantations still retains the largest concentration of Negro population. Furthermore, over 40 per cent of the total Negro population of the country still constitute the majority of the population in the central plantation area, and close to 20 per cent of the total number of Negroes in the country live on the fringes of this area of continuous Negro majority. Only 26 per cent of the Negro population live in an area totally free from the direct economic bonds of the plantation system.

But this condition has not been and is not a static one. What has been the history of the distribution of Negro population? And in this connection, does the present area of continuous Negro majority also have historical continuity?

The area of continuous Negro majority was established under the chattel slave system. It had already taken form in the South Atlantic seaboard regions during the colonial period. Its creator and its jailor was the plantation.

Chattel slavery was the only means of assuring a labor supply on the plantations. Early colonists could take with them a working force of indentured servants, but they could not transport the capitalist relations of production with which to force workers to remain wage slaves or starve. There were no masses to be expropriated from the land and transformed into an army of wage workers; instead there was a tremendous extent of free public property which could be transformed into private property and individual means of production by these very indentured servants. These forced laborers soon turned settlers on their own account and together with the free colonists were creating in the North the basis for the development of the capitalist relations of production.

But the plantation system which had been established along feudal European lines in the Virginia colony, and which served as a model for the later plantations in the South, could not flourish as long as its labor supply remained uncertain. The slave trade, which in time assured the major portion of the wealth accumulated by the northern merchant capitalists, found at hand in the insipid southern plantation, the form of exploitation best adapted to slave labor. The products of the early plantations in Virginia, Maryland and along the southern Atlantic coast—tobacco, indigo and rice— and the topography of the Coastal Plain, lent themselves to largescale cultivation by gangs of laborers under close supervision. Transported from a decimated homeland, the African Negro found himself thrust immediately into a discipline of the most primitive and direct form of forced labor, in a social environment which was entirely strange to him. His ties with his own social base had been completely and irrevocably sundered. Out of the background of his fellow slaves he could not even piece together common bonds which could serve as the starting point for creating the solidarity of a uniform social class. His fellow slaves came from diverse peoples of Africa, in varying stages of social development, and spoke different languages. It was only within the completely new conditions of the slave economy, with the past practically a total vacuum, that the slaves could develop mutual bonds and a common language, and create a new social consciousness. Clearly designated from the rest of the population by marked physical characteristics, the Negro slave could not, like the indentured servant, find refuge in the expanse of unsettled land, although some of them did make common cause with Indian tribes.

The concentration of large numbers of slaves on the plantations was an unavoidable weakness of the slave regime. Living in daily contact with each other, subject to uniform conditions of exploitation and of life, the slaves soon developed that class solidarity which, in the form of numerous slave revolts, presented a constant danger to the Bourbon power. ‘The concentration of the slave population facilitated the development of a new people, the American Negro, who is far more a product of the southern plantation than of the Africa of a dim past.

Even in the early period, when the plantation system was taking form and before cotton became the stimulus for its rapid expansion, the Negroes were a significant part of the population in the southern colonies. From some early census enumerations supervised by the British Board of Trade, from estimates of colonial officers and references in contemporary diaries and letters, it is possible to piece together a record of southern population before the first federal census of 1790.2 From this data it would seem that South Carolina had a Negro majority since 1699, when, it was estimated, there were four Negroes to each white man; at any rate it seems to be fairly established that between 1715 and the Revolutionary War, when a large number of slaves were deported by the British, the Negroes were in the majority in the colony, although the 1790 Census reported that the proportion of Negroes was only 44 per cent. A census of Virginia in 1755 reported 103,407 “tithables”, of whom 60,078 were Negroes. In 1790 the Negroes were 34.7 per cent of the total population of Maryland, 26.8 per cent in North Carolina and 41 per cent in Virginia. Georgia, a late comer among the colonies, in 1790 already counted 35.9 per cent of its total population as Negro.

The Negro slaves were concentrated, however, in those areas where a staple crop made possible cultivation of large fields under the plantation system. Thus, before it was discovered that rice could be grown along the South Carolina coast, the settlers were getting on as best they could in small-scale and individual farming units. But in 1694 rice was introduced from Madagascar, and when its cultivation proved successful, a large number of slaves were imported. By 1708, an official count of the population along the seaboard of what is now South Carolina revealed 3,500 whites, of whom 120 were indentured servants, 4,100 Negro slaves, and 1,400 Indians held in captivity. The slave population increased with the growth of rice production:

“ . . In 1724 the whites were estimated at 14,000, the slaves at 32,000 and the rice export was about 4,000 tons; in 1794 the whites were said to be nearly 25,000, the slaves at least 39,000 and the rice export some 14,000 tons, valued at nearly 100,000 pounds sterling; and in 1765 the whites were about 40,000, the slaves about 90,000 and the rice export about 32,000 tons, worth some 225,000 pounds.”3

A similar development took place on the tobacco plantations of Virginia, which in 1619 received the first group of slaves to be landed on the North American mainland. By the end of the century the Negroes formed the bulk of the plantation gangs.4

Although the manor system was already well established in Maryland by the latter part of the 17th century, the planters could not afford to buy many slaves because of the poor quality of the tobacco, and there were more indentured servants on the plantations than Negroes. In the tobacco-producing colony of North Carolina the first comers arrived in 1660, but these and those who followed continued as small farmers. Only above Albemarle Sound, in the northeastern section of the state, did the plantation system attain full development, and to this day the Negroes still outnumber the whites in this region. “Towards the South, however, the land was too barren and the system of agriculture developed on the basis of small proprietorship. Negroes never formed a large part of the population. North Carolina, with the exception of the northeast where the early plantations were located, does not today have an agrarian economy fully typical of the Black Belt and has a correspondingly lower proportion of Negroes.

The forms of exploitation developed even during the early colonial period left an indelible mark on the future history of the South. Wherever the plantation system was deeply rooted, no matter how much it deteriorated later, it left powerful remnants which persist to the present time. A state census of certain Virginia counties was taken in 1782-1783. In eight of these counties the average slave-holding ranged from 8.5 to 13 slaves, 15 planters had more than 100 slaves, and 45 planters between 50 and ]00 slaves.5 Although the plantation has deteriorated in these regions the same eight counties are today situated in the Virginia section of the Black Belt.6 Similarly, the three chief plantation counties of Maryland, according to the 1790 Census, had about the same scale of slaveholding as the eight Virginia counties. Yet, despite the close proximity of these counties to the North and to areas of high industrial development, they are to be found today bordering on the northern tip of the Black Belt.

The South Carolina colony offers an even more striking comparison. By 1790, indigo which had gradually replaced rice was in turn giving way to cotton in the area around Charleston. The change in product did not necessitate a change in the system of exploitation. According to the federal census of that year, among the 1,643 heads of families in the Charleston District there were 1,318 slaveholders owning 42,949 slaves. The rest of the South Carolina coast, comprising the Georgetown district to the North of Charleston and Beaufort to the South, had a similar scale of slave-holdings.7 Today in the counties of Georgetown, Charleston and Beaufort the percentages of Negroes in the population are 64.4, 54.2 and 71.4, respectively.

Even before the cotton gin was invented (1793), the plantation system was already well developed in Virginia, Maryland, northern North Carolina and along the South Carolina coast into Georgia. In the plantation regions of these colonies, the Negroes already constituted the majority of the population. Within a decade after its invention, the cotton gin was in widespread use and driving cotton cultivation westward at a tremendous pace. When the slave trade was formally closed by an act of Congress in 1808, there were already 1,000,000 Negro slaves in the country. Their numbers multiplied by forced breeding on the old plantations and, supplemented by additional slaves smuggled into the country, they served as the source of labor supply for the new plantations. By 1809 cotton was already a staple in the settlement around Vicksburg in the Mississippi territory; but prior to the War of 1812 the cotton plantation developed principally into the Carolina-Georgia Piedmont and tended south-westward into Alabama.8 This section, the oldest large-scale cotton growing region in the South, forms the Carolina-Georgia region of the Black Belt today.

In the meantime, sugar plantations were being founded in the delta lands of southeastern Louisiana. The labor supply from the Atlantic Coast was supplemented by slaves brought over from San Domingo by landowners fleeing the slave revolution. By 1830 there were 691 sugar plantations with 36,000 working slaves in this area and by 1850 the number of slaves in the sugar parishes had doubled.9 This region is to be found within the present Black Belt.

While the westward movements in the North and into Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri carried with them the seed of capitalist development in the form of self-sufficing pioneer farming, the westward movement in the South extended the “cotton kingdom”. After the capture of Mobile from Spain during the War of 1812 and the defeat of the Indians assured an outlet for the products of the interior cotton plantations, the movement into Alabama and Mississippi developed rapidly. Between 1810 and 1860 the population of Alabama and Mississippi grew from 200,000 to 1,660,000 and the proportion of slaves from 40 per cent to 47 per cent. During the same period the slave regime expanded through Louisiana and into Arkansas and Texas. The barren soil in Florida saved it from the plantation, and with the exception of a small region to the northwest, it remains outside of the Black Belt today.

The black soil prairies across central Alabama, which is today an area of great density of Negro population, was first opened to cotton culture in 1814 and within 20 years the slave plantation system was extending throughout its whole length. The Mississippi River valley, reaching from Tennessee and Arkansas to the mouth of the Red River, today the largest plantation area in the Black Belt, had already been rather well settled by 1840.

By 1860, on the eve of the revolution which would destroy it, the slave regime had reached its zenith. ‘The capitalist power of the North had already become strong enough to hinder further expansion westward. The limits of the slave plantation area in 1860 also mark the limits of the area of continuous Negro majority. The 1930 Black Belt remains essentially the same area on which the mass of Negroes were enslaved by King Cotton, waving the sceptre of chattel slavery. Impose the outlines of the area of continuous Negro majority in 1930 upon an economic map of the South of 1860, and see that they are almost identical with the plantation area of 70 years ago! “Free” capitalism has not weakened the rule of King Cotton, but only placed another sceptre in his hand.

As long as chattel slavery ruled the South, an open and direct form of forced labor bound the Negro masses to the plantation. A measure of the effectiveness with which the Civil War broke these bonds should be found in the degree to which the area of continuous Negro concentration was dissipated and the Negro population more evenly distributed over the United States in the period which followed. Real freedom would have released the slave to become either a landowner himself or a wage-worker free to sell his labor power to a capitalist farmer or to the manufacturers of the North who were so urgently in need of it that they went to all lengths to obtain it in Europe. In reality, however, the Black Belt did not only remain intact, but in that continuous area in which the Negro was in the majority in 1930, the Negro population had almost doubled by 1910. This was due neither to a breaking up of the plantation system into individual farms owned by Negroes nor to industrial development in this area. The plantation, utilizing other forms of labor, has succeeded over this long period in holding the Negro population prisoner.

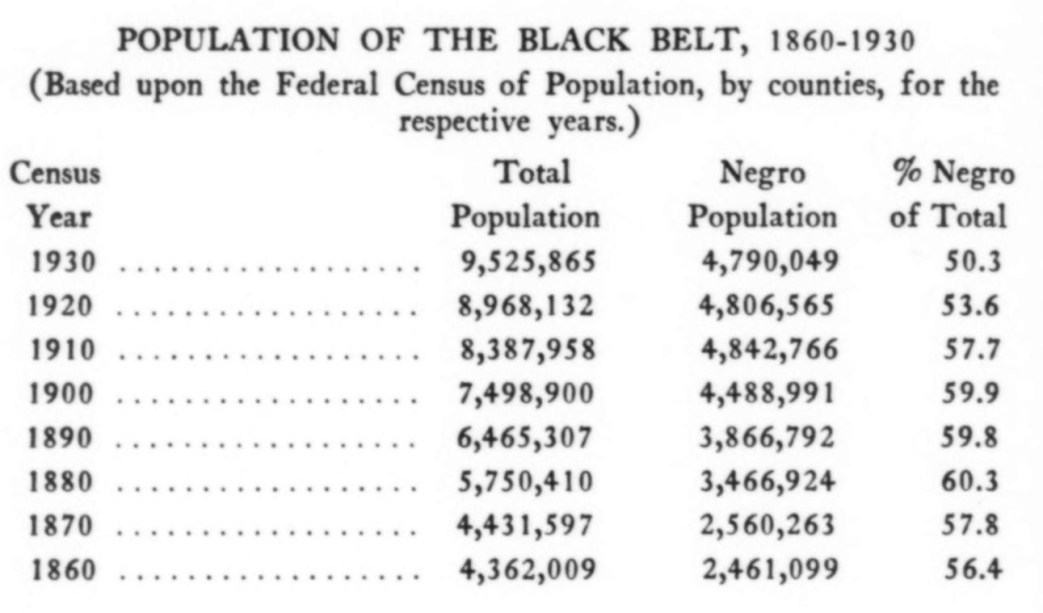

But the plantation economy had to contend with antagonistic forces. Comparing the population of the 1930 area of Negro majority with the population of the same territory for each decade since 1860, we obtain the following results:

This comparison shows that in the continuous area in which Negroes were half of the total population in 1930 they had previously constituted a larger proportion of the population. If, instead, the area of bare Negro majority were calculated for each decade separately, it could be shown that a larger area of Negro majority existed with little change until 1910. Between 1910 and 1930 it is evident that forces were operating which tended to dissipate the concentration of Negro population. While the Negro population of the Black Belt had increased by 96 per cent between 1860 and 1910, the white population had only increased 86 per cent during the same period. But between 1910 and 1930 the white population increased by 33 percent while the Negro population decreased by slightly over one per cent. Furthermore, factors were operating which left the rate of increase of the white population practically uniform in the Black Belt while exerting their main influence upon the Negroes. This is shown in the comparison of the rates of increase for the white and Negro population by decades. The increase recorded for the white population fluctuated between 13 per cent and 17 per cent. It is difficult to generalize on the rate of increase of the Negro population because of the undercounts in the various census enumerations, although a downward tendency probably began in 1900-1910. In the next two decades the Negro population decreased at the rate of 0.8 per cent and 0.3 per cent, respectively, representing an absolute loss in population of 52,717 in the entire Black Belt Proper.10 The reduced proportion of the Negroes in the population of the Black Belt was, therefore, the sum total of an increasing white population and a decrease in the number of Negro inhabitants after 1910.

While a small decrease in the proportion of Negroes in the total population of the Border Territory took place during the same period, there was no absolute loss in Negro population, although the rate of increase did tend downward after 1910.

During the period between the census enumerations of 1910 and 1930 there occurred the mass migration of Negroes into the North and the most intensive industrialization yet experienced by the South. In many quarters these events were hailed as nothing more nor less than the beginning of a rapid dissolution of the Black Belt, of a process of final disintegration of its plantation economy, and of the more even distribution of the Negro population in the country as a whole. In short, capitalism was now solving within its own confines and in a gradual, peaceful manner, without the discomforts of an agrarian mass upheaval on the plantations, those very problems which the Civil War period of revolution had left unsettled. True, the development of a revolutionary working class movement throughout the country would have been accelerated and the working class would have been spared the struggle against the heritage of the chattel slavery if the Civil War had accomplished its historic aims in full, if it had wiped out the economic vestige of the slave system in the form of the plantation and established the basis for Negro equality in capitalist society; or, failing this, if the forces of industrialization had been able to migrate the Black Belt out of existence, accelerate the process of assimilation, and at most leave the Negro question as one of achieving equal rights for a people no longer bound by the economic hang-overs of chattel slavery. To the measure that these things are accomplished under capitalism the proletarian revolution is so much to the good. But we are concerned with realities and not with useless speculation about the ifs of history.

In reality, the “epoch-making” events of 1910-1930 while inflicting some damage upon the prison bars of the Black Belt, did not remove them. Without at this point examining the results produced in the Black Belt economy, but limiting ourselves to the results of these forces as reflected in the population movements, we note the following changes.

The whole area did not respond uniformly. Because of internal developments and its geographical location, the Virginia region (I) of the Black Belt was more subject to the influences of industrialization. Despite the presence of fairly large cities and ports, the effect of industrialization was felt from an early date in a tendency to dissipate the Negro majority. The Negro population of this region had a low and static rate of increase since 1880, and prior to that date large numbers of Negro toilers had migrated into the newer plantation areas of the Mississippi Valley. In 1880 the region still counted 56.3 per cent of its population Negro, but by 1910 less than half of its inhabitants (49.2 per cent) were Negroes and in 1930 the proportion had been reduced to 43.7 per cent. Yet, the rate at which the Negro concentration was reduced is surprisingly low, in view of the especially favorable position of this area in relation to areas of more developed capitalism and to such large cities as Baltimore and Washington.

In the North Carolina region of the Black Belt, small-scale farming and some internal industrialization have contributed in retaining the Negro population. Here there has been practically no change in the proportion of Negroes since 1860, and a stable and high rate of increase was maintained throughout the period. Finally, in the Texas-Louisiana region (VI on the map), the latest plantation area fully developed under the slave regime, there was a rapid rise in the rate of increase in the Negro population in the decade 1920-1930 (17.6 as compared with 3.3 for the previous decade and 6.3 for 1900-1910).

It is precisely in the most extensive area of the plantation economy, in the South Carolina-Georgia, Alabama-Mississippi and Mississippi Valley Black Belt (Regions III, IV and V), which in 1930 contained 77 per cent of the total Negro population of the Black Belt, that the developments during the last two decades produced their most profound results. But how extensive were these results, how much had capitalism actually been able to accomplish towards balancing the social deficit of its revolutionary Civil War?

Already during the decade 1900-1910 a decline in the rate of increase of the Negro population of the three regions was apparent. The proportion of Negroes declined from 62 per cent in 1900 to 60 per cent in 1910. From 1910 to 1930 the Negro population had decreased by 4.8 per cent, while the white population increased 31 per cent. Despite the decrease in the absolute Negro population, and the further increase in the white population, the proportion of Negroes was reduced in this area as a whole only to 52 per cent in 1930. In face of the array of powerful forces which tended to drain the Black Belt of its Negro population, these plantation regions retained a decided Negro majority.

It is important to note, however, that during this 20-year period an absolute decrease in the Negro population occurred only in the older plantation regions comprised in the South Carolina-Georgia and Alabama Black Belts (Regions III and IV). The Negro population in these regions decreased 10 per cent. In the Mississippi Valley (Region V), on the other hand, the center of the largescale and highly organized plantations, the Negro population had increased about 4 per cent. To the degree that these population statistics reflect the results of forces antagonistic to the plantation economy, we may conclude that the plantation suffered most precisely where it was weakest. Thus, the oldest of the three plantation regions, South Carolina-Georgia, was able to retain its Negro population and even increase it during 1910-1920, but in the following decade, when it suffered most from the agricultural crisis, it lost 11.2 per cent of its Negro population. The reverse process occurred in Alabama-Mississippi and the Valley. During 19101920 the former lost 11.7 per cent of its Negro population, the latter 2.4 per cent. But during the next ten years the trend was reversed in both these regions, the Negro populations having increased by 1.3 per cent and 6.6 per cent respectively.

Of course, the developments of the last 20 years produced other effects upon the Black Belt economy, not shown by the population figures. But the area of continuous Negro majority has only been slightly altered, indicating that those factors which have in the past confined a large proportion of the Negro people to the territorial limits set by the slave regime still persist.

However, an important redistribution of the Negro population has taken place. In 1860, 55.4 per cent of the Negro population was located in the Black Belt, 15.8 per cent in the Border Territory, 15.2 in other southern territory and 13.6 per cent in the North. During the course of the next 50 years a very slow and gradual redistribution occurred. After a half-century of freedom, no least important part of which is the freedom to move from especially oppressive conditions, the Black Belt still retained 49.3 per cent of all Negroes living in the United States. More of the Negro population was subjected to the only slightly less unbearable conditions of the Black Belt periphery which now contained 20.7 per cent of the Negro population, while only an additional 1.4 per cent over 1860 was found in the North. The most drastic change occurred between 1910 and 1930, when the distribution was as follows: Black Belt, 40.3 per cent; Border Territory, 19.8 per cent; other southern territory, 13.8 per cent; North (including an insignificant number in the West), 26.1 per cent.

The progressive features of this redistribution cannot be overlooked. Some hundreds of thousands of Negro toilers have escaped from the stifling slave atmosphere of the Black Belt. This did not change the situation there fundamentally; in fact, it depleted the Black Belt of its most aggressive and militant Negro toilers, Nor does it mean that the Negro masses who found their way to other parts of the country had discovered the “promised land” of freedom. Its significance lies in the increase of the number of Negro industrial proletarians and their entry into the modern class struggle. Freed at least from the direct economic bonds of the plantation system, a larger proportion of the Negro masses were now living in areas of more highly developed capitalism where conditions were more favorable for the development of the Negro middle class. The process of class differentiation among the Negro people was accelerated. The struggle for full emancipation was raised to a higher plane and brought into living contact with the more advanced section of the working class movement. Under the special conditions of the War and Post-War period, capitalism in the United States had been able to engender a movement which it had stifled during the preceding half century.

Is this a tendency which can be expected to continue at the swift pace of the last two decades, or even at a more moderate rate? Yes, say pseudo-Marxists such as Norman Thomas, and also Leninists such as Jay Lovestone and his followers, following the usual bourgeois interpretation of recent developments in the South. This is as much as to say that capitalism in the United States is able to overcome one of its sharpest basic contradictions by destroying the economic remnants of slavery and to perform the progressive task of removing the main economic base for the subjection of the Negro people. This is an axiom of the Socialist Party position, as expressed by Norman Thomas, that “what the Negro wants and needs is what the white worker wants and needs; neither more nor less;” and of the Lovestonite vigorous denial of the national nature of the Negro question. These gentlemen have complacently “overlooked” one of the most important peculiarities of the development of American capitalism which has at the same time become one of its greatest contradictions. If the proletariat were to take their advice and blissfully leave a basic task of its own revolution in the benevolent hands of capitalism heavy with fascism, it would not only weaken its own class solidarity of white and Negro workers, but lose one of its most effective allies in the struggle against capitalism and endanger the success of the proletarian revolution. Our answer to this question is a decisive no! Further on we analyze those factors which brought about the changes of the War and post-War period, their effects upon the economic remnants of slavery, the nature of industrialization in the South and its effects upon the Black Belt economy, the development of capitalism in southern agriculture, and the present situation in the South in relation to that stage of development in which capitalism finds itself today. Only one conclusion is possible on the basis of these facts: The recent redistribution of the Negro population did not constitute a tendency, but only a temporary movement stimulated by transitory factors which impressed certain important new characteristics on the Negro question without changing its fundamental nature. In fact, since the beginning of the economic crisis there has even been a reversal of the movement of population from the Black Belt. Up to 1910 capitalist development in the South did not weaken, but strengthened the plantation economy; after that capitalism was no longer able to uproot the hang-overs of chattel slavery, so intimately had they become intertwined in its own structure; instead, it is being strangled by them. The historic task of destroying the last vestige of chattel slavery and achieving Negro liberation falls within the domain of the proletarian revolution

* Unless otherwise stated, the term South is used to denote only those states, portions of which lie in the Black Belt: Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas and Arkansas. The census designation South includes, in addition to the above, Delaware, West Virginia, Kentucky and Oklahoma.

Notes.

1. New Leader, July 23, 1932.

2. These figures have been collected in American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790, by Evarts B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington, New York, 1932.

3. Ulrich B. Phillips, American Negro Slavery. A Survey of the Supply, Employment and Control of Negro Labor as Determined by the Plantation Regime, New York, 1929, p. 87.

4. Ibid., p. 75.

5. Cited by Phillips, #bid., p. 83.

6. The counties and the proportion of Negroes in their total populations in 1930 are: Amelia, 51%; Hanover, 37%; Lancaster, 45%; Middlesex, 46%; New Kent, 59%; Richmond, 39%; Surry, 60%; and Warwick, 37%.

7. Ibid., pp. 95-96.

8. Ibid., pp. 159-160.

9. Ibid., pp. 166-167.

10. In addition to the absolute loss in Negro population, the Black Belt also lost the natural increase, other things being equal, for this period. In the section on the migration, it is shown that about 1,000,000 Negroes migrated out of the Black Belt in the period 1910-1930.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v13n06-jun-1934-communist.pdf