Artist and Marxist art critic reviews the latest ‘discoveries,’ and the imperialist expansion behind them, in pre-historic art and wishes for a future intellectual world vibrant enough to ‘unravel their mysteries.’

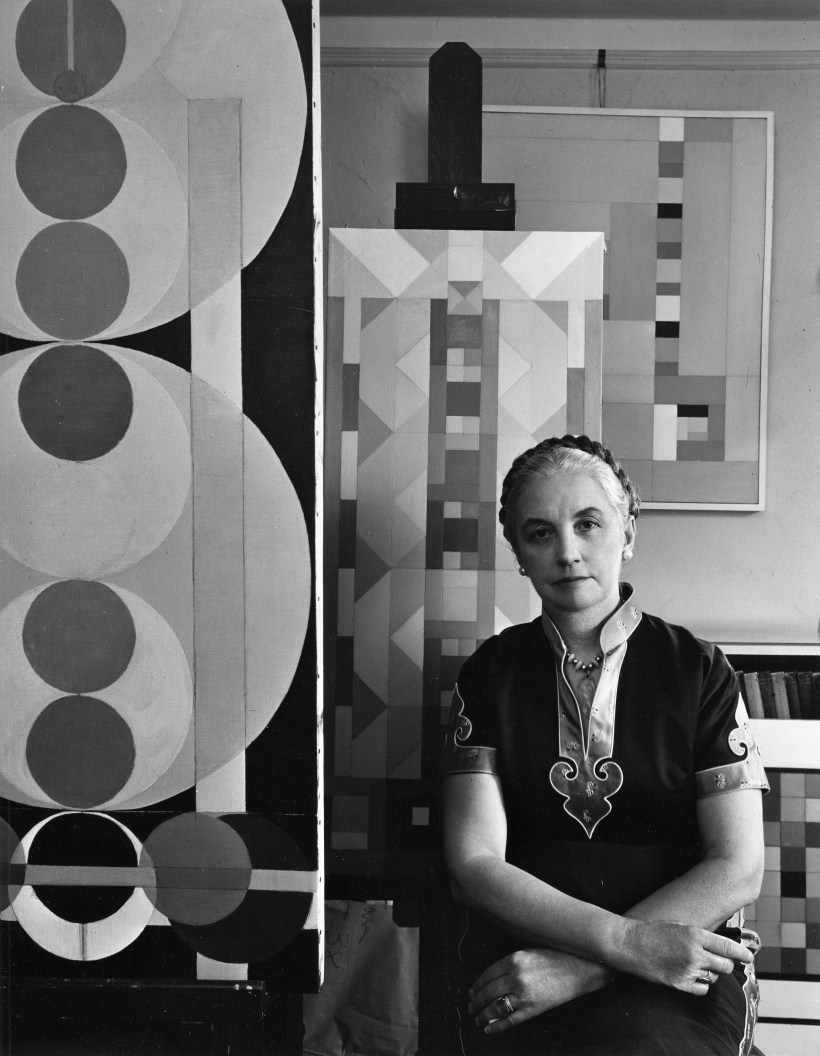

‘Pre-historic Rock Pictures’ by Charmion von Wiegand from Art Front. Vol. 3 No. 5. June-July, 1937.

WHILE the expansionist movement of imperialism in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries was occupied with the conquest of markets and colonies in the pre-industrialized sections of Asia and Africa, the same impulse in science was pushing back the then known boundaries of the physical universe and exploring ever further into the past history of mankind. Successive new archaeological discoveries greatly enlarged our perspective of the past. Pompei and Herculaneum disinterred gave us back the intimate Iuxuries of the Roman world; Schliemann taking his Iliad as literal truth conjured up the Homeric Age from the ruins of Troy and Mycenae. Egypt’s mighty past was unrolled in a series of excavations lasting down to the present moment. But even further back there existed prehistoric man with no written records. The skeletons of the Neanderthal and Cro-Magnan man predicated a savage animal existence without any cultural activity.

In 1895, Europe was startled by the announcement that in the Altamira Caves in Spain, first opened in 1867, there existed animal paintings of wonderful artistry and that these were not products of some itinerant later artist but actual relics of a civilization that existed over 20,000 years ago. Scientists brought up on the Darwinian theory of evolution were immediately antagonistic, for here was no primitive or savage painting but highly coordinated artistic creation. These monumental bisons were not only on an artistic level with subsequent delineation of animal life but actually in some ways superior. Here was an art that used impressionist methods to portray the essential form that had mastered the rendition of muscular tension and organic vitality.

The theory of the time held that this great art of the Ice Age found in the French and Spanish caves had perished at the end of the glacial period. Certainly Neolithic art, formal and static in pattern, revealed no trace of its influence. But Leo Frobenius, a young student of anthropology, who was present when the letter of Riviere, the French discoverer of Altamira painting, was read before the Berlin Anthropological Society, refused to accept this theory. He could not believe that such a vital, highly developed art could perish so completely.

He recalled that Spain had once been part of Africa, which at the end of the Ice Age was a tropic land fertilized by a heavy rainfall from the melting of the glaciers. Perhaps in that flood period, prehistoric man had migrated from the Iberian peninsula southward and remains of his culture could be unearthed in Africa. Certain tribes of African bushmen still paint crude pictures on rocks. Might these not be the last living remnants of Ice Age culture? This scientific guess of Frobenius was the beginning of a long series of amazing discoveries.

The German-Inner-African Research Expedition organized by Frobenius sent out its first expedition in 1904. To date it has conducted over a dozen successive expeditions in Africa and in Europe on prehistoric sites. The story of these discoveries is closely related to Germany’s imperialist thrust into Africa. But work did not stop even after the war and the German revolution. In 1923 the Research Institute for the Morphology of Civilization at Frankfort-am-Main was founded. The present exhibition of prehistoric rock paintings al the Museum of Modern Art has been brought over from this institute’s collection of over 35,000 facsimiles of prehistoric materials.

These discoveries now offer a survey of the distribution of prehistoric European art in Africa. They have not been without influence on European life and art. The peoples of Africa and Asia, subjected to ruthless exploitation and economic slavery during the stampede for markets, have had a certain revenge. For just as the Romans, who brought back the eastern gods and arts of the vanquished tribes as spoils to decorate their palaces were in their turn conquered by them, so pre-war Europe was effected by the exotic arts of Africa and the East. The old African tribal gods, the savage rhythmic dances, the exotic handicrafts and magic art of Africa made a triumphal conquest of European art. Morocco, Tunis, Japan, China, India, the South Seas, the Argentine, Mexico, each in turn and finally Africa and prehistoric culture have all had their day in modernist painting. Like the drowning man, who in the last instant of consciousness reviews his whole life from his earliest childhood memories, so capitalist society was reviewing the whole history of mankind before plunging into the catastrophe of world war.

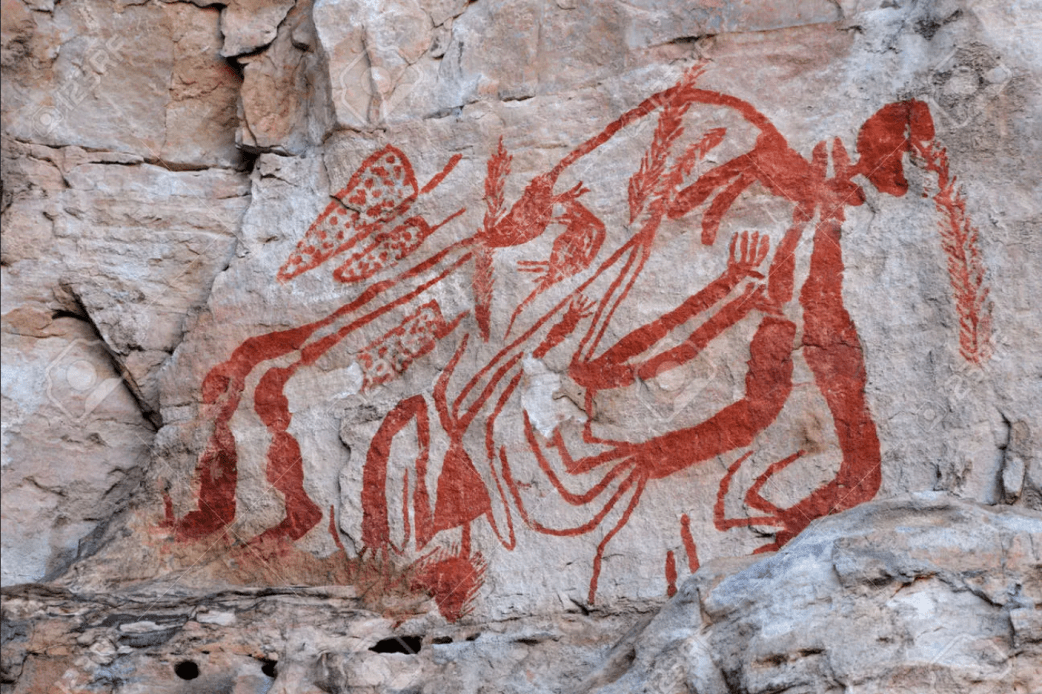

It is the timely aspect of this prehistoric painting which has led the Museum of Modern Art, devoted exclusively to contemporary culture, to hold this exhibition, To stress their point, they have included a room full of modernist painters where Miro, Masson, Klee, Arp, Lebedev, and Larionov demonstrate their apparent kinship to the oldest painting in the world. Certainly the newly discovered rock painting from the Libyan desert might at first glance be taken for the patterns of abstract surrealism, but at bottom the resemblance is superficial. For primitive painting was magic which had a practical function. Before setting forth to kill an animal, the hunter dramatized it pictorially. This was a magic rite to ensure success and to ward off the evil spirit of the slain animal. In the earliest culture, an attempt was made to approximate nature as closely as possible, no doubt to make the magic more efficacious. But later, perhaps due to haste and the fact that such a mural was immediately comprehensible to the tribe, a shortcut or stylization of the act occurred. Finally the original naturalistic representation becomes a symbolic sign language approaching abstract terms. But the abstract pattern of such a rite retained the original content and was immediately decipherable. The content of modern surrealists is not at all comprehensible to their audience. Its symbolism drawn from the unconscious is often deeply personal and not communicable. Such incomprehensibility may be considered rather an evasion of social reality, which has become too chaotic and contradictory to face even in pictorial terms. The only practical function which surrealism so far has performed is the subjective reflection of the disintegration of bourgeois society. Thus there is no real analogy and certainly no organic relationship between pre-historic art and the latest manifestations of European art, which are entirely a product of their social milieu.

While bourgeois science has given us the material remains of a world that existed when Europe was covered with glaciers, it has not solved the meaning of these relics. Today we know how the man of the Ice Age lived, sheltered in caves, wandering nomadically following the trail of bear, elephant, elk, bison, wild horse, mammoth and reindeer, kept from penetrating northward by a glittering chain of glaciers. We know his ignorance of pottery and of agriculture, his skill at hunting, his weapons of flint, his amazing realistic art. Caves sealed since the dawn of time have opened to reveal his foot prints, his ochre-daubed hands on their-walls, the flint palette knife stuck fast in the rock beside his mural, his paint box of earth colors and animal fats. From over 550 sites, relics of the lce Age culture have been excavated and in 187 of them have been found engravings and paint on rock.

Yet no one has yet adequately explained how it happened that two totally diverse cultures existed contemporaneously so long ago. In Altamira and in the other caves of southern France and Spain we find a realistic and monumental art of animal portraiture. This polychrome painting in illusionist style with sharp contrasts between light and dark, has been termed Franco-canlabrian art. Weapons found with it are the most ancient known-the spear and dart. Once its influence extended as far north as England, as far east as South Russia and Siberia, and as far south as Africa.

But there was found on boulders and overhanging rocks in the open a totally different art, which has been labeled Eastern Spanish or Levant style. Here shadow silhouettes in monochrome, chiefly red earth, portray man in active movement, leaping, running, jumping, hunting. Although man is here the chief subject, the world is seen in the image of animal life and of man’s close relationship to it. Here the weapons depicted are always the bow and arrow of the tropics. Once it might have been assumed that these two styles derived from diverse cultures and could have developed in different epochs but in 1932, in the rocky wastes of Fezzan, Frobenius made one of the most important prehistoric discoveries of our time. Engraved on desolate high rock terraces, he found hundreds of mammoth portraits of elephants, lions, giraffes and other wild animals from ten to twelve feet high in the Franco–camabrian style. Beside them chiseled deep in the stone were paintings of the Levant type. Further expeditions in 1933 and 1935 traced the spread of the Levant style of art at the Libyan desert, where pre-Egyptian paintings were found.

The resurrection of these two antipodal pre-historic cultures and the tracing of them from Europe to Africa, where they continued to survive side by side, is not only a matter of interest for anthropologists. A study of these two styles of mural painting from the dawn mankind has an immediate practical interest for artists today. In their origin, both styles reveal an intense pre-occupation with the natural world. Here minute observation of the momentary aspects of reality emphasize., everything tactual. Form is a matter of contour; outlines are frequently engraved. These pre-historic artists knew and mastered many of the problems of modern art. They studied perspective, movement, chia-ruscuro.

Nor were the great Franco-cantabri.an murals hastily executed. Thirty years after the discovery of paintings in the Font-deGaume cave in France, the original sketches for the same murals, done on stones the size of a plate, were discovered in another cave. Developed Franco-camabrian painting reveals an ever increasing plastic conception of animal life. Structure and muscular tension are dramatized through contrasts of light and dark spots and broken contour, so that a three dimensional art emerges, an art that does not slavishly imitate but seizes on the essential unity of the organism and renders it impressionistically. Naturally these early artists were not concerned with esthetics or expression of personality; their art, like their religion, as revealed in their painting, was highly purposive, intent on gaining “control of the sensory world.” It expressed their life-with its unstable, nomadic, hunting economy.

While the purpose of Levant art must have been identical with that of the Franco-cantabrian art, it developed a totally different expression. Franco-cantabrian artist were familiar with many pigments such as ochre, brown iron, red iron, yellow iron ochre, black manganese, and white chalk; Levant art is for the most part monochrome. Dealing with man as well as animals, it is much richer in movement, stressing always the tense, leaping, quick movements of both. It depicts both the action of animals and the active magic of man seeking to control them. The scale of its figures while larger in Africa than in Spain is always much smaller than the Franco-cantabrian.

In the Neo-lithic age, a new world came into being. The roving nomad of the Ice Age was no more. The glaciers had melted. The forests grew and plant life developed. The present European rivers came into being. Man began his long struggle to wrest subsistence from the earth itself. Hunting ceased to be the prime occupation when primitive agriculture developed. Fertility was essential, and as it could not he represented pictorially it was magically ensured through symbols. Animal painting is now replaced by amulets. Late Levant painting shows an increasing stylization and a tendency to become static. These so-called “degenerating” forms in which naturalistic rendition gradually becomes increasingly formal, marks a transition to a new form of social organization. The marvelous accuracy of natural observation for individual animals is replaced by group relationships in stylized patterns which tend toward the abstract. Representation of light, air, movement is avoided. By the time of the bronze age, art ceases to be realistic and seeks its ultimate goal in a static geometry. Egyptian art is the highest development of this tendency.

While both Crete and Greece were later to create a new naturalistic art focused on organic form, it was not until centuries later that the depiction of animal life could achieve, on another social level, the incredible vitality and truth of the art of the Ice Age.

Perhaps the future is not distant when Marxist science will unravel the mysteries of pre-historic human relationships and thus lay hare the social roots out of which grew these two diverse styles in pre-historic culture. Engels was the first to attempt an interpretation of the social organization of primitive man. In our day Freud has sought to reconstruct his primitive mentality. Bourgeois science has assembled all this vast material out of the distant past. But as yet no one has charted the laws by which the pendulum in art swings from the pole of representation to the pole of abstraction and back again or how those changes relate to changes in the body of society itself.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v3n05-p3-p6-missing-june-july-1937-Art-Front.pdf