Art Shields with another fantastic piece of labor reporting, this time on the I.W.W.’s San Pedro port strike. It ends with an ominous warning about the Klan being sicced on the strikers which would happen shortly after.

‘The San Pedro Strike’ by Art Shields from The Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 1 No. 2. June, 1923.

I HAVE just come from the city of San Pedro, the port of Los Angeles, where one of the most remarkable strikes in the history of American labor is now going on. I am frankly amazed at what I saw there and so is everyone else coming into the town, and so are the people of San Pedro themselves.

What, San Pedro, the busiest port on the Pacific tied up tight, and by the wobblies? Impossible! The report was so extraordinary that I came down from San Francisco on a voluntary investigation tour to see for myself. I had passed through San Pedro earlier in the year on an intercoastal freighter and had seen no signs of a labor sunrise. At that time the town was in the hollow of the shipowners’ hand. Mr. Nichols’ “scab hall,” as the shipowners’ employment office is colloquially called, was handling the labor problem with thorough satisfaction to the employers, and there was no organized protest from the workers Longshoremen who denied union membership were allowed to work from eight in the morning till eleven at night, when ships were in. They were driven at insane speed and accidents were frequent. I have never seen winch drivers swing cargo with such desperate hurry as at San Pedro, or stevedores plunge about so frantically. Nor was this all. Longshoremen told me that the worker who fell under the frown of Mr. Nichols as a union suspect, or for any other reason, went on the scrap heap. Women used to go down and weep to him to give their husbands a share of the work so they could eat, but to no use; Mr. Nichols got a kick out of being hard.

As for the wobblies, yes, there were a few, but most of them were in jail. The sovereign state of California makes it a crime, punishable by one to fourteen years imprisonment, to belong to the industrial union movement. Today the law is a farce in San Pedro. Two thousand folk of the town are openly carrying I.W.W. cards and seem very proud of it. This criminal Syndicalism law is now getting a dose of the same wholesome irreverence that I saw the liberty-loving miners of Kansas pay Governor Allen’s Industrial Court. But three months ago how different it was in San Pedro. In those days the wobblies were a small minority and Swelled Out Authority jumped on them as hard as bullies can.

I.W.W. Educational Campaign

What I did not know then was that these hundred or so I.W.W.’s were carrying on a quiet but effective educational campaign that has perhaps never been equaled in such a short space of time. In three months, from January to April, every house in San Pedro received three pamphlets and other literature setting forth in clear and simple language the benefits of organization! How to do away with the tyranny of the “scab hall”; how to raise wages to a living standard and to equalize working hours so that every one would have his share of labor instead of one getting sixteen hours a day and the other none. All these problems were dealt with and the literature also took up the ultimate program of the I.W.W., its plan for the final emancipation of labor from the idlers who live on its back. And, more particularly, the free literature exposed the infamous criminal syndicalism law of California, which sends workingmen to penitentiaries for fighting for better living conditions.

No brass banding marked this work that paved the way for the big strike. The longshoremen and sailors who were distributing this literature and giving street talks in between jailings, knew how to get results. They knew their people. They knew that their fellow workers, the other sailors and longshoremen who make up the bulk of the population of this marine city, would listen to the facts presented in a reasonable way.

The result was that membership in the Marine Transport Workers’ Industrial Union began to grow quietly, but by hundreds. The union had no hall, only a “floating headquarters,” but its strength began to bulge up on all sides. And when the big strike call for the release of the labor prisoners, the elimination of the “scab hall” and the improvement of job conditions went out April 25, San Pedro went over the top. As the strike progressed swarms of sympathizers joined the union, and the Marine Transport Federation, a smaller and unaffiliated organization, fell in line. And then came the merchants.

One Hundred Ships Tied Up

In a week the strike was ninety-five per cent effective. As I write, one hundred ships are tied up in the harbor. Lumber schooners loaded weeks ago in Puget Sound, Coos Bay, Oregon, or Eureka, Cal., lie idle at their wharves. Cargo vessels of all nationalities are anchored in the outer harbor or crowding the almost deserted docking spaces. A half dozen lines have already declared an embargo on freight to San Pedro and railroad companies are cutting off car service from the shipping companies because of insufficiency of business.

This big strike has grown to such proportions that it can no longer be called a mere I.W.W. strike. Nor even a mere waterfront strike. It passed through both those phases. Today it is a community affair. The people of San Pedro as a whole are back of it and the red label doesn’t bother them. The sentiment is astonishing. At last night’s meeting I heard the wife of a local business man make a strike speech and hand a check for twenty-five dollars to the committee. A few nights before, the names of sixty business men, mostly small merchants, were read off as strike fund contributors, the sums ranging from one dollar to one hundred. And the Japanese fishermen of East San Pedro were among the contributors. The fact that every member of the strike finance committee which handles this relief money is a member in good standing of the I.W.W. and carries a red card in his pocket in spite of the syndicalism law does not bother the donors a bit. They know the boys. They are their customers and friends and they want them to win so there will be more prosperity for all.

Down with Hootch!

I was about to add here that the Industrial Workers of the World have twice the influence of any force in San Pedro, but I will not do so. It would sound like propaganda and my trade is that of a newspaperman, not a propagandist. Instead I make a significant statement that speaks for itself. The I.W.W. has closed up the bootleggers for the duration of the strike. It did this by its own authority and in its own way, and without the fuss and flurry, the sly tasting and sensational raidings of the official closers. The ukase against bootlegging was read out at the first mass meeting and it was enforced. And now the bootleggers are on strike too, as one of the clan put it sadly and meekly.

In a week’s time I saw only two men under the influence of liquor, and they but slightly. Both came from Los Angeles. San Pedro is as dry as Charles W. Wood found Emporia, Kansas, as related in a recent issue of Colliers’ Weekly.

The wobbly dry action made me decidedly curious. I had always known the industrial unionists as a group that dealt with job reform to the exclusion of the sopcalled political issues, and this action led me to ask questions of the strike committee.

“Nothing strange,” they said. ‘‘We’re out to win this strike and no bootlegger is going to stop us.”

“Boozing might ruin the strike,” they explained. “If one of our boys got drunk he would be apple pie for some agent provocateur to incite to some act that would hurt the organization. And another thing: We don’t want anyone throwing away eight dollars a quart for “‘jackass’” when there are women and babies to be fed.”

It sounded logical so far, but there was something else I couldn’t understand.

“Why is it,” I asked, “that the zealous police force of San Pedro and the federal agents haven’t taken the initiative in this?”

“They are too busy,” smilingly answered a wobbly; “too busy arresting workingmen.” He was one of the defendants in the Los Angeles criminal syndicalism trial, now out on bail and assisting in the strike.

Another thing I was about to say was that this is a young man’s strike, but the memory of a grey-haired, sinewy veteran, Fellow Worker Gelpke, stops me. Gelpke says he is a real Industrial Worker of the World because he has worked in industry in each of the five continents of the world. He took a sixty-day jolt as a wobbly last winter without minding it a bit, and is one of the most effective speakers in San Pedro. And is he enjoying himself? Say, you should have heard his greeting, “‘Ain’t she a moose?” when I stopped him on the street and asked him about the strike.

Free Speech Fights

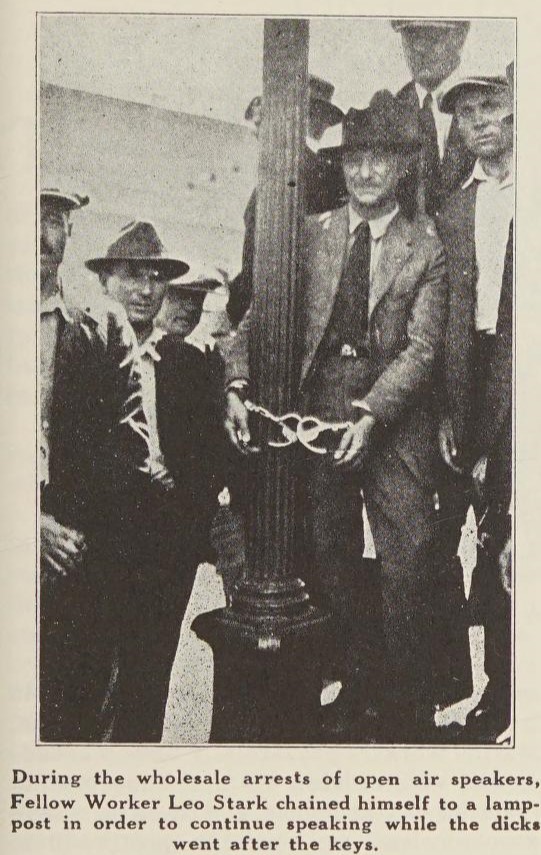

Somewhere in this magazine you will see a picture of Leo Stark handcuffed to a telegraph pole. It was his way of winning a free speech fight. He guaranteed that the police couldn’t drag him away till he had finished his organization talk. That was the night Captain Plummer’s brave “bulls” arrested thirty wobblies for exercising their constitutional rights of free speech, and it was before a woman loaned her lot on Liberty Hill to the strikers for their meetings. Well, Leo Stark isn’t exactly a youngster, though he’s only been in the radical labor movement for thirty or forty years in nearly as many continents as Gelpke. Stark is a speaker and newsboy. He sells five hundred copies of each issue of “The Industrial Pioneer,” “Industrial Solidarity” and “Industrial Worker,” and is said to be a wizard at disposing of wobbly song books, pamphlets, and so forth. Of course he’s out on bail as a criminal syndicalist and has a forty-day jail term awaiting him for a street speech charge, but that doesn’t bother him after the Wichita oil workers’ case, in which he invested four years.

One might go on to mention some of the vivid old veterans among the Spaniards and Mexicans who make up half the working force of San Pedro. Particularly in my mind there stands out one keen old strategist, a sturdy, grizzled fellow, with black eyes glowing out over high bronzed cheek bones and an aquiline nose. He is a man of much influence among his countrymen in surrounding towns and the steps he has taken to ensure solidarity from the Mexicans in the coast towns to the south would make an article in itself. And they have been effective. There is even less scabbing from Mexicans than from others.

But the young men are in the majority. They are running the strike committee, publicity committee, finance committee, launch committee, and so forth, and they pack the grounds on Liberty Hill where the strike meetings are held twice a day. And when the songs of labor brotherhood are sung there under the stars it is an inspiration to hear their clear voices rise in the night.

Wobbly Enthusiasm

I had heard that the days of wobbly singing were over, that the movement had become too hard-headed for music, but San Pedro dispels that illusion that came from too long a sojourn with the theoreticians of the East. I have never heard anything sung with more enthusiasm than the song that peals from the throats of thousands every night on Liberty Hill. It is the class-war prisoners’ song “Remember,” which Harrison George wrote in the Cook county jail, with its commanding refrain:

“Remember you’re outside for us. And we’re in here for you.”

That is the outstanding thought in this strike which was primarily called for the release of the class-war prisoners. The illusion is forever shattered in me that the American workingman would fight for nothing but more “pork chops.” The fact is that the strikers here in San Pedro are talking more about forcing the release of their fellow workers from Leavenworth, Walla Walla, San Quentin and other prisons that for anything else, even the abolition of the hated “scab hall.” And by the class-war prisoners they do not mean only wobblies. Mooney and Billings are emphasized as much as Ford and Suhr. Every speaker, and there are many,—rank and file speakers talking five minutes each—stresses the demand for the release of the federal and state prisoners and the abolition of the syndicalism law.

Will the strikers win? That depends on the rest of the marine industry. San Pedro is a safe unit in the fight. The men are determined and their wives are behind them. Economic support is coming from all sides. Two bakeries are supplying free bread and wobbly fishermen give a ton of fish a day to the needy and money is given freely. San Pedro is doing its part.

One thing seems certain. The movement in San Pedro is now so deeply grounded that it will not blow away. It is grounded on a clear understanding, by hundreds of active members, of the issues involved. It is an unusually intelligent rank and file. Marine workers proverbially have a broader and clearer view of world movements than the stay-at-homes, and these men have also received an enviable postgraduate educational training in the last three months in San Pedro. Best of all, the movement is organized on broad human lines and is not limited and sectarian. That is shown by the policy of extending relief to all workingmen, whether members of the I.W.W. or not. The movement, though under the banner of the I.W.W., is a popular community movement against local injustices and vicious state and national persecution of labor.

Against such a wall the propaganda of hate of the Los Angeles Times and the San Pedro Pilot, a slimy local sheet which is trying to sic the Ku Klux Klan against the strikers, will beat in vain.

And ornithologists say the raven is croaking over the ‘‘scab hall.”

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/industrial-pioneer_1923-06_1_2/industrial-pioneer_1923-06_1_2.pdf