Claude McKay, who had previously written for the U.N.I.A.’s ‘Negro World,’ with a critical essay on the politics of Marcus Garvey.

‘Garvey As a Negro Moses’ by Claude McKay from The Liberator. Vol. 5 No. 4. April. 1922.

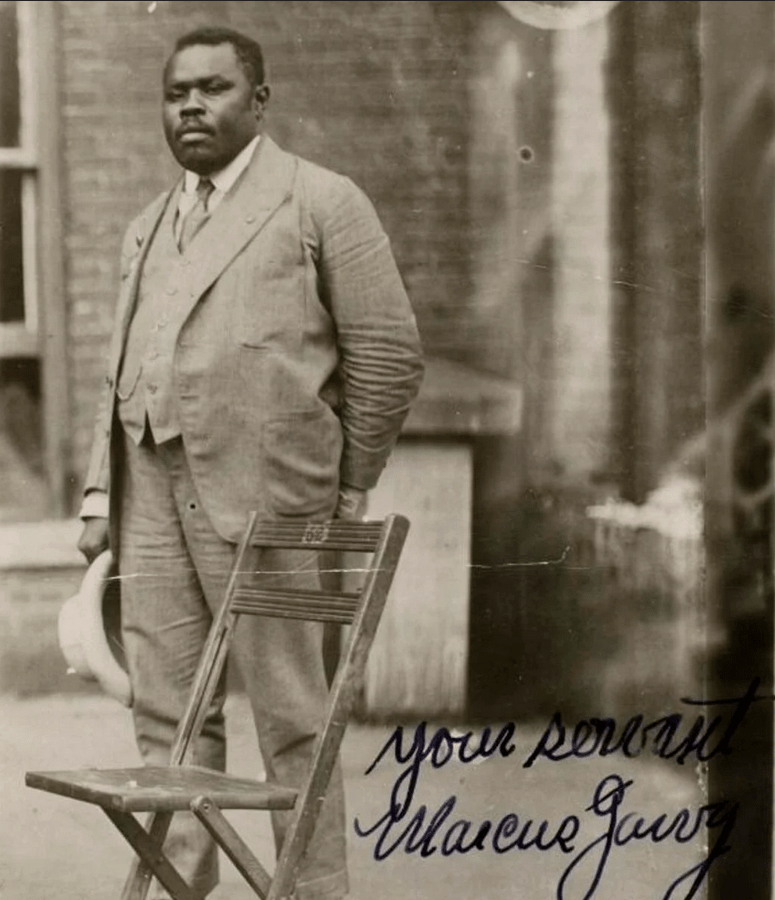

GARVEYISM is a well-worn word in Negro New York. And it is known among all the Negroes of America, and throughout the world, wherever there are race-conscious Negro groups. But while Garvey is a sort of magic name to the ignorant black masses, the Negro intelligentsia thinks that by his spectacular antics-words big with bombast, colorful robes, Anglo-Saxon titles of nobility (Sir William Ferris, K.C.O.N., for instance, his editor and Lady Henrietta Vinton Davis, his international organizer), his steam-roller-like mass meetings and parades and lamentable business ventures- Garvey has muddied the waters of the Negro movement for freedom and put the race back for many years. But the followers of Marcus Garvey, who are legion and noisy as a tambourine yard party, give him the crown of Negro leadership. Garvey, they assert, with his Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Black Star Line, has given the Negro problem a universal advertisement and made it as popular as Negro minstrelsy. Where men like Booker T. Washington, Dr. DuBois of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and William Monroe Trotter of the Equal Rights League had but little success, Garvey succeeded in bringing the Associated Press to his knees every time he bellowed. And his words were trumpeted round the degenerate pale-face world trembling with fear of the new Negro.

To those who know Jamaica, the homeland of Marcus Garvey, Garveyism inevitably suggests the name of Bedwardism.

Bedwardism is the name of a religious sect there, purely native in its emotional and external features and patterned after the Baptists. It is the true religion of thousands of natives, calling themselves Bedwardites. It was founded by an illiterate black giant named Bedward about 25 years ago, who claimed medicinal and healing properties for a sandy little hole beside a quiet river that flowed calmly to the sea through the eastern part of Jamaica. In the beginning prophet Bedward was a stock newspaper joke; but when thousands began flocking to hear the gigantic whiterobed servant of God at his quarterly baptism, and the police were hard put to handle the crowds, the British Government in Jamaica became irritated. Bedward was warned and threatened and even persecuted a little, but his thousands of followers stood more firmly by him and made him rich with great presents of food, clothing, jewelry and money. So Bedward waxed fat in body and spirit. He began a great building of stone to the God of Bedwardism which he declared could not be finished until the Second Coming of Christ. And in the plenitude of his powers he sat in his large yard under an orange tree, his wife and grown children, all good Bedwardites, around him, and gave out words of wisdom on his religion and upon topical questions to the pilgrims who went daily to worship and to obtain a bottle of water from the holy hole. The most recent news of the prophet was his arrest by the government for causing hundreds of his followers to sell all their possessions and come together at his home in August Town to witness his annunciation; for on a certain day at noon, he had said, he would ascend into heaven upon a crescent moon. The devout sold and gave away all their property and flocked to August Town, and the hour of the certain day came and passed with Bedward waiting in his robes, and days followed and weeks after. Then his flock of sheep, now turned into a hungry, destitute, despairing mob, howled like hyenas and fought each other until the Government interfered.

It may be that the notorious career of Bedward, the prophet, worked unconsciously upon Marcus Garey’s mind and made him work out his plans along similar spectacular lines. But between the mentality of both men there is no comparison. While Bedward was a huge inflated bag of bombast loaded with ignorance and superstition, Garvey’s is beyond doubt a very energetic and quick-witted mind, barb-wired by the imperial traditions of nineteenth-century England. His spirit is revolutionary, but his intellect does not understand the significance of modern revolutionary developments. Maybe he chose not to understand, he may have realized that a resolute facing of facts would make puerile his beautiful schemes for the redemption of the continent of Africa.

It is rather strange that Garvey’s political ideas should be so curiously bourgeois-obsolete and fantastically utopian. For he is not of the school of Negro leader that has existed solely on the pecuniary crumbs of Republican politics and democratic philanthropy, and who is absolutely incapable of understanding the Negro-proletarian point of view and the philosophy of the working class movement. On the contrary, Garvey’s background is very industrial, for in the West Indies the Negro problem is peculiarly economic, and prejudice is, English-wise, more of class than of race. The flame of revolt must have stirred in Garvey in his early youth when he found the doors to higher education barred against him through economic pressure. For when he became a printer by trade in Kingston he was active in organizing the compositors, and he was the leader of the printers’ strike there, 10 years ago, during which time he brought out a special propaganda sheet for the strikers. The strike failed and Garvey went to Europe, returning to Jamaica after a few months’ stay abroad, to start his Universal Negro Society. He failed at this in Jamaica, where a tropical laziness settles like a warm fog over the island. Coming to New York in 1917, he struck the black belt like a cyclone, and there lay the foundation of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Black Star Line.

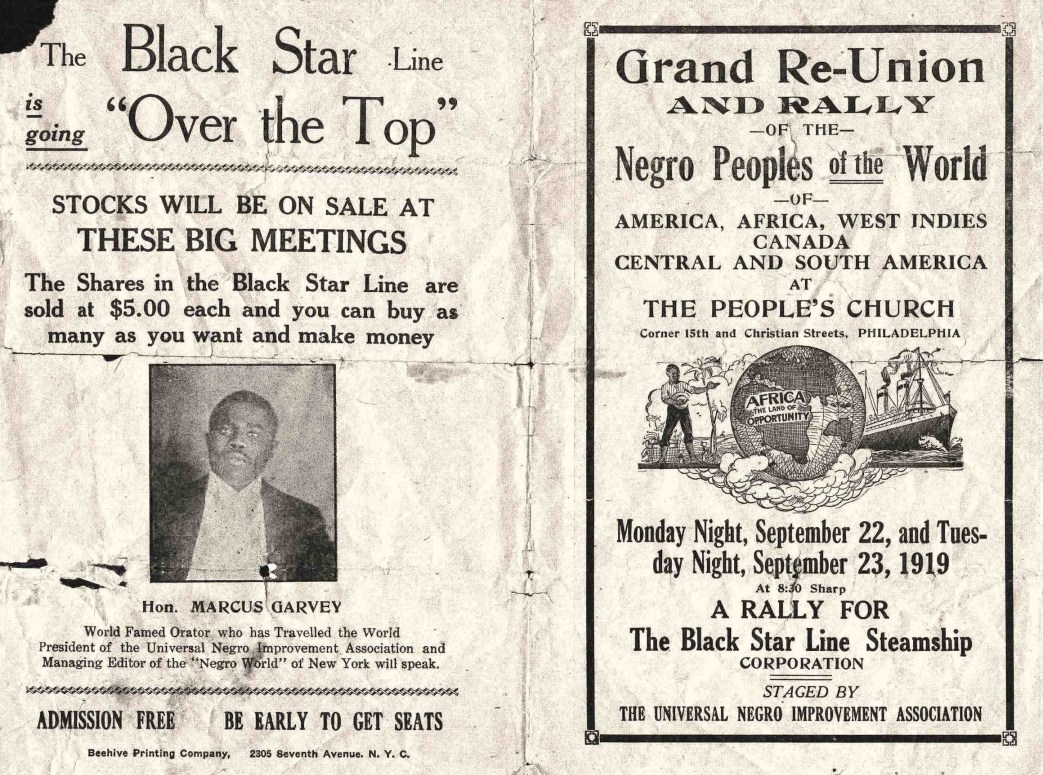

At that time the World War had opened up a new field for colored workers. There was less race discrimination in the ranks of labor and the factory gates swung open to the Negro worker. There was plenty of money to spare. Garvey began his “Back to Africa” propaganda in the streets of Harlem, and in a few months he had made his organ “The Negro World,” the best edited colored weekly in New York. The launching of the Black Star Line project was the grand event of the movement among all Garveyites, and it had an electrifying effect upon all the Negro peoples of the world- even the black intelligentsia. It landed on the front page of the white press and made good copy for the liberal weeklies and: the incorruptible monthlies. The “Negro World” circulated 60,000 copies, and a perusal of its correspondence page showed letters breathing an intense love for Africa from the farthest ends of the world. The movement for African redemption had taken definite form in the minds of Western Negroes, and the respectable Negro uplift organizations were shaken up to realize the significance of “Back to Africa.” The money for shares of the Black Star Linepoured in in hundreds and thousands of dollars, some brilliant Negro leaders were drawn to the organization, and the little Negro press barked at Garvey from every part of the country, questioning his integrity and impugning his motives. And Garvey, Hearst-like, thundered back his threats at the critics through the “Negro World” and was soon involved in a net of law suits. The most puzzling thing about the “Back to Africa” propaganda is the leader’s repudiation of all the fundamentals of the black worker’s economic struggle. No intelligent Negro dare deny the almost miraculous effect and the world-wide breadth and sweep of Garvey’s propaganda methods. But all those who think broadly on social conditions are amazed at Garvey’s ignorance and his intolerance of modern social ideas. To him Queen Victoria and Lincoln are the greatest figures in history because they both freed the slaves, and the Negro race will never reach the heights of greatness until it has produced such types. He talks of Africa as if it were a little island in the Caribbean Sea. Ignoring all geographical and political divisions, he gives his followers the idea that that vast continent of diverse tribes consists of a large homogenous nation of natives struggling for freedom and waiting for the Western Negroesto come and help them drive out the European exploiters. He has never urged Negroes to organize in industrial unions. He only exhorted them to get money, buy shares in his African steamship line, and join his Universal Association. And thousands of American and West Indian Negroes responded with eagerness.

He denounced the Socialists and Bolshevists for plotting to demoralize the Negro workers and bring them under the control of white labor. And in the same breath he attacked the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and its founder, Dr. DuBois, for including white leaders and members. In the face of his very capable mulatto and octoroon colleagues, he advocated an all-sable nation of Negroes to be governed strictly after the English plan with Marcus Garvey as supreme head.

He organized a Negro Legion and a Negro Red Cross in the heart of Harlem. The Black Star line consisted of two unseaworthy boats and the Negro Factories Corporation was mainly existent on paper. But it seems that Garvey’s sole satisfaction in his business venture was the presenting of grandiose visions to his crowd.

Garvey’s arrest by the Federal authorities after five years of stupendous vaudeville is a fitting climax. He should feel now an ultimate satisfaction in the fact that he was a universal advertising manager. He was the biggest popularizer of the Negro problem, especially among Negroes, since “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” He attained the sublime. During the last days he waxed more falsely eloquent in his tall talks on the Negro Conquest of Africa, and when the clansmen yelled their approval and clamored for more, in his gorgeous robes, he lifted his hands to the low ceiling in a weird pose, his huge ugly bulk cowing the crowd, and told how the mysteries of African magic had been revealed to him, and how he would use them to put the white man to confusion and drive him out of Africa.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1922/04/v5n04-w49-apr-1922-liberator-hr.pdf