Substantial report from the Parti communiste français on the activity of its then 56,000 members between 1924 and 1928, including its press, factional struggles, campaigns, work among women, among peasants, among co-operatives, and among unions, as well as an overview of the economic and political situation in the country, its labor unions, and Socialist Party. In the 1928 election, the PCF received 1,066,099 votes, or 11.26%.

‘Report of the French Communist Party’ from The Communist International Between the Fifth and the Sixth Congresses, 1924-28. Published by the Communist International, 1928.

THE ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL SITUATION.

WHILE the national economy of France (particularly as regards industry) has undergone a rapid development since 1921, except during the first years of the occupation of the Ruhr, it is, nevertheless, true that there have been difficult, if not critical, periods. Already at the beginning of 1926 there were symptoms of coming difficulties, and new international and national conditions arose which placed obstacles in the way of “facile development,” such as had been artificially stimulated in the preceding years. Development was slowing down. The keynote of the period which followed the war, and which went on until after 1921, was expansion of finance capital, appropriation of the industries of Alsace Lorraine, Luxemburg, and the Saar, enormous investments in Central and Eastern Europe. It was also a period of spoilation of State possessions and public funds, of continuous growth of fixed capital invested in enterprises, of repairs and renewals of plant, and of the starting of fresh concerns. The reconstruction of the devastated regions and the modernisation of enterprises in the rest of France brought an enormous growth in the productive capacity of the industries.

The policy of the Government, inspired and directed by the central committees of the big industries and the big banks, the interests of which had finally become identical, was one of encouraging this fever of expansion. By means of internal loans and of partition of the “damages” to the capitalists of the regions under reconstruction, finance capital succeeded in pressing into its service the possessions and the money of the great majority of the population, particularly of the peasantry.

This formidable growth of the industrial apparatus created immediately three urgent necessities: the securing or conquering of markets and outlets; the finding of money in order to set enterprises going; the provision of the necessary labour power. For the special and provisional “national outlet” (the reconstruction of the devastated regions) was nearing: its end, and would soon disappear. The internal loans had exhausted the resources of the peasantry and the petty bourgeoisie, and the national supply of labour power was insufficient.

Thus it became necessary to introduce foreign labour en masse, to occupy the Ruhr, to instigate wars in Morocco and Syria, and to adopt the policy of inflation. The policy of inflation enabled finance capital to appropriate the remaining pecuniary resources of the peasantry and the petty bourgeoisie. It enabled it to camouflage the low real wage of the workers and thus to compete easily on the world market. It enabled it artificially to increase industrial production. But this did not last long. At the end of 1925 and the beginning of 1926 important changes took place in the situation on the international market. American and British finance capital had already decided to demand the “monetary stabilisation” of France, because French inflation was becoming more and more harmful to American and British interests. In France itself, inflation was beginning to create difficulties and social-economic trouble, it was prejudicial even to several categories of capitalists. At the end of 1925 and the beginning of 1926 the campaign for the “stabilisation” of the franc and of the finances of the State was at its height.

From then onwards the question was not: is “stabilisation” necessary, but what class, what Government, what party shall operate this “stabilisation,” and in what manner? The series of Ministerial crises during 1925 and in the first half of 1926, all of them provoked by the fierce struggles around the question of inflation and “stabilisation,” were, in fact, nothing but the consequence of the stubborn determination of the big bourgeoisie to solve these questions entirely in its on class interests.

While the politicians of the “Left” bloc looked upon the financial problem as a “technical problem,” the big bourgeoisie looked upon it as a political problem, and made of it a political issue, leaving it to the Banque de France and the other banks to pull the strings and exhaust, compromise, ridicule, and finally drive out the bloc governments. At the end of June, 1926, a committee of financial experts, consisting of representatives of the big banks and big industries, was already functioning side by side with the official Government, acting as the real Government. This committee worked out the conditions and methods of “stabilisation.” The report of the Financiers’ Committee became the credo of the general politics of the National Union Government under the Presidency of Poincaré. The main problem was solved: the big bourgeoisie obtained the political conditions which it stipulated for the “stabilisation” of the franc and of the State finances. From July, 1926, and during the whole of 1927 the “National Union” Government did nothing but apply step by step, successively, the prescriptions and directions formulated by the Financiers’ Committee.

The de facto stabilisation of the franc, already almost realised towards the end of 1926, revealed the existence of a state of economic crisis. Unemployment set in in November, 1926, it increased in December, and again in the beginning of 1927. A general industrial and commercial retrogression set in. This state of slow, chronic, non-catastrophic crisis, which, by the by, is not yet overcome, has ushered in a new stage in the orientation of the development of the national economy of France and in the policy of the bourgeoisie and the Government.

The most characteristic features of this new stage are:

The rationalisation of industrial enterprises inspired and directed by finance capital and effected mainly through the centralisation of concerns and the elimination of the less profitable, and through worsening the position of the workers (lower wages, longer working hours, intensification of the productivity of labour); strengthening the constitution of the cartels and trusts and of their monopolist spheres; free export of French capital and its investment in foreign enterprises as well as in the form of State loans; free investment in France of foreign capital; reinforcement of protective tariffs, particularly import duties on coal, metal, manufactured articles, and even on agricultural produce. The big metal and chemical industries are indirectly protected by their position of absolute monopoly in the French market and by their international entente (respectively European) with regard to the foreign market.

Another characteristic of this situation is the increased cost of living (high prices in the interior of France), accompanied by very low real wages owing to the offensive of the employers. At the same time more and more symptoms appear of a worsening of the position of the small peasants and a considerable section of the urban petty bourgeoisie.

Gradually, and as a result of the changes which took place in the national economy, there arose also more or less serious changes in the correlation of the class forces. We witness an objective economic and political reinforcement of the big bourgeoisie which is now better organised nationally and less disrupted than before by group antagonisms. This class, as its imperialist aspirations increase, having been taught a lesson by the revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe since 1917, has pursued, end is still pursuing, the policy of an excessive reinforcement of the State apparatus to serve its own purposes; it is also gradually repealing all the reforms which it was formerly compelled to concede to the workers and their organisations.

Foreseeing inevitable struggles in the near future by the proletariat and the dissatisfaction of the toiling masses (particularly the peasantry), as well as the possibility of another world crisis, of another imperialist war, of a fresh wave of the struggles among the colonial peoples, the French capitalists and their successive Governments are taking political and administrative measures in order to strengthen their control over the army, to purge the political machine of petty bourgeoisie elements and to disorganise, if not destroy, the class organisations of the proletariat and the Communist Party. But parallel with this policy and in order to make it more effective, the capitalists continue their work of methodical corruption among the working class by making use of leaders of the reformist C.G.T. and of the Socialist Party, as well as of the leaders of all the so-called “Left” political parties and groups in order to induce a section of the toiling masses and of the workers to collaborate in the capitalist “rationalisation,” in the strengthening of military forces, in the popularisation of nationalist and colonialist ideologies and in serving the imperialist policy of belittling and libeling the Soviet Union and the Communist movement.

The attitude of the so-called “Left” parties, including the Socialist Party, since May, 1924; that is to say, since the coming into power of the “Left” bloc which, in regard to all the problems which concern the working class, continues the policy of the preceding “national bloc,” became once more manifest at the time of the recent elections (April, 1928). This attitude is thoroughly anti-Labour and anti-Communist. The “Left” parties were only too pleased to identify themselves with the policy pursued by Poincaré. The fact that a Poincaré National Union Cabinet, that is to say, an entirely bourgeois and thoroughly reactionary Cabinet has been able to retain power since July, 1926, owing to a “Left” bloc Parliamentary majority, and owing also to the fact that it was precisely the “Left” members of this Cabinet who, at the command of big capital, ordered the prosecution and repression of the workers and the Communists; these facts show clearly how intensified the antagonism and the struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat has become. For its part, the working class, becoming more and more concentrated in big concerns, baffled and taken by surprise for a time when the period of unemployment set in, is beginning to come to pull itself together and to resist the endeavour of the employers to lower wages. It is beginning to struggle, and is preparing to assume the offensive. The imposing demonstrations in the summer and autumn of 1927, and the strike wave in the winter of 1927 and at the beginning of 1928, show this clearly. The working class is gradually getting rid of the influence of petty bourgeois and bourgeois politicians, it is visibly moving to the “Left,” and is sympathising more and more with the Communists.

While during the preceding period the class struggle was mainly concentrated around financial questions (inflation, stablisation), around the general economic policy of the Governments and around the question of “putting the State apparatus on a healthy basis,” at present the “social question,” that is to say, the direct energetic and fierce struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie is once more becoming the centre of political life. “Class against class,” merciless, hard and relentless struggle, such is the characteristic feature of the present period.

As to the international position of French capitalism and of French policy, the following facts are characteristic:

Having tried immediately after the war and particularly at the time of the occupation of the Ruhr to secure economic hegemony Over Europe, French imperialism suffered a defeat owing to the rival pressure of the British and North American imperialisms. Since then it has been maneuvering alternatively or simultaneously in the colonies, in Asia Minor, in North Africa, in the Far East, in Central and Eastern Europe, in the Balkans, and in South America. On the industrial field, as an exporter, France is coming more and more into collisions, particularly with German and North American competition. The antagonisms between French and Italian imperialism with regard to the colonies in North Africa and Asia Minor are very strong, and also with regard to their aspirations and interests in the Balkans. The antagonism between British and French imperialism is on the increase on the European continent, because of Germany and of the countries bordering on the Soviet Union; also with regard to Asia Minor and Tangiers, as well as with regard to armaments. These antagonisms made themselves continually felt at the various sessions of the League of Nations; although an improvement has taken place in Franco-German relations and several attempts have been made at an economic and even political rapprochement, the constitution of an entente and of a Franco-German bloc is still problematic. On the other hand, a very pronounced evolution is noticeable in the imperialist policy of France with regard to the U.S.S.R. and the colonial movements. This evolution takes the form that in this sphere French imperialism is becoming more and more the auxiliary and loyal collaborator of British imperialism. The financial, industrial and administrative circles and their press are working more and more for an economic blockade of the U.S.S.R. The new Chamber with its majority of the representatives of the big industrial capitalists—even if it does not create the basis, since that existed already—will at least provide the formal facilities for increasing the aggressiveness of French imperialist policy. Thus we witness the reinforcement of political and police reaction within the country, the open or concealed destruction of the last vestiges of the former democratic traditions, the extreme development of militarism, the accentuation of the aggressiveness of foreign policy. Such are the main features characterising the present attitude of French imperialism, showing that the antagonisms in the class struggle are on the increase.

The Socialist Party, S.F.I.O.

The Socialist Party has played an important and active role in the development of the imperialist France of the post-war period by giving support to the efforts of the big industrial and finance capitalists to stabilise and consolidate their regime. As a component part of the Left bloc, which came into power in May 1924 owing to the opposition of the mass of workers, peasants and petty bourgeois elements to the imperialist policy of big capital represented by Poincare, the Socialist Party shared responsibility for the whole policy of the bloc.

Its participation was effective although it decided not to form part of the Government. Its policy of ‘support’ was not only a passive participation in the policy of bloc Governments; it was active collaboration with the Government, it was manifest in the acceptance, on the part of some of the elected socialists, of important State posts (Varenne, governor of Indo-China, Boncour, representative of France in the League of Nations); in votes for the budgets, etc.

During the four years of office the Socialist Party never ceased being the active agent of capitalist stabilisation; it never ceased supporting, defending and being at the service of the imperialist policy of big capital. It became colonialist: it opposed the action of the Communist Party which demanded the evacuation of the colonies; it voted credits for the predatory war in Morocco; it took an active part in the work connected with the military reorganisation of French imperialism; it was Pau! Boncour, instructed and supported by the C.A.P. and the Socialist fraction in the Chamber, who was the author of the Bill which lays the foundation of the new French military power and organises the complete militarisation of the country, including women and children, old men and trade unions, under the direction of the professional military cadres, specially recruited for internal police duty against the working class. The Socialist Party has expressed itself in favour of capitalist rationalisation and helps in its application. After accepting recognition of the U.S.S.R. when this was dictated by the interests of the big capitalists, and because it helped to deceive the masses who demanded this recognition; it shamelessly fostered the campaign of the British oi] kings and of the venal French press for the severance of relations with the U.S.S.R. by pouring on the Soviet Union a flood of gross insults and calumnies, even trying at the time of the elections, to emulate the British conservatives with their Zinoviev Letter by the story of the alleged intervention of Litvinov in the French elections.

The Socialist Party played an active part in the anti-Communist repression. It dared not, in the face of the working class vote for the imprisonment of Communists, but it voted for the secret funds of the political police, thus allowing the development of the network of detectives and agents provocateurs and the intensification of repression; it voted for the reform of the electoral system which openly aimed at depriving the Communist Party, in favour of the reactionaries of the parliamentary representation to which it had a right. Thereby the Communist group which should have had 65 members was reduced to 14: finally it supported the Pamleve Government which initiated the prosecution of Communists at the time of the Moroccan war.

In Alsace Lorraine the S.P. was the most active agent of French imperialism and chauvinism in stifling all aspirations of the national minorities towards autonomy. This consistent and active collaboration with the bourgeoisie showed itself in systematic refusals to establish a united front with the Communist Party for the campaigns directed against colonialism, militarism and the wars in Morocco and Syria, for the U.S.S.R. and the Chinese revolution.

At the second ballot in the parliamentary elections, socialists preferred alliance with the bourgeoisie and with Poincare, and contemptuously refused to form a proletarian bloc.

Their policy of “active support” during the first years of the bloc became a policy of ‘passive support” and of seeming opposition when Poincare came again into power and governed in the name of big capital. But their greatest concern was a policy of “laissez faire” with regard to Poincare, who congratulated them on this loyal opposition which was the most adequate form of support which the socialists could give him. Without obstructing in any way the policy of the government by their seeming opposition, they carried on frantic campaigns in order to prevent the mass of the workers and peasants coming entirely under Communist influence.

What was the repercussion of this policy within the socialist party and in its relations with the masses?

The question which dominated the internal life of the Socialist Party was that of participation in the government. The Right wing—Renaudel-Boncour—endeavoured to secure the effective participation of the S.F.I.O. Party in the government.

Although they continually gained ground within the party, Blum’s policy with regard to the government remained the official policy. It allowed him to enjoy the advantages of participation and at the same time to discard the responsibilities in the eyes of the masses. Another question which dominated the interna) life of the Socialist Party was that of relations between it and the other parties—Communist to the Left, radical Socialists to the Right—in connection with the election tactic. The Right expressed itself openly in favour of a systematic alliance with the radical socialists and “all honest republicans” against the Communists, “class against class”! The extreme Left with the “Etincelle” group was for the united front—as a prelude to organisational unity with the Communist Party. The centre (Blum, Paul Faure), and the “Left” (Brake) with the wobblers on the Right and on the Left demanded that the Socialist Party should stay sitting on the fence, in order not to lose its influence with the working class on the one hand, and to be able to continue its policy of class collaboration on the other.

The extreme Left allows itself to be used in this game by talking of a possible organisational unity between the Socialist and the Communist Party, and by keeping alive among the Socialist masses the illusion of a possible rectification of the Party.

This demagogy, intended to deceive the masses, has only partly succeeded. The results of the April elections, 1928, show that in the most important working class districts which remained strongholds of the Socialist Party (Nord, Pas-de-Calais, Haute-Vienne, Loire, Saone et Loire) an evident and important change has taken place, many working class socialists voting for the Communist Party.

Probably the result of such a loss of influence will be shown in increased demagogy. Without in the least relinquishing its policy of class collaboration, the Socialist Party will try to have recourse to revolutionary phraseology and oppositional gestures in order to deceive the masses and to prevent them from coming under the influence of the Communist Party.

The entire internal life of the party consists of questions of parliamentary and electoral tactics.

The Reformist C.G.T.

The policy of class collaboration and of active support of imperialism which is a characteristic feature of the Socialist Party is also the main feature of the line taken by the reformist C.G.T. There is a difference not of character, but only of degree.

The reformist C.G.T. carries out the policy of the Right Wing of the Socialist Party; it does not endeavour to maintain an equilibrium between two extreme wings; It combats the unitarian Left without mercy and expels it; it practises class collaboration openly and cynically. Jouhaux is, side by side with Boncour, the representative of French imperialism in the League of Nations and in the various farces which it organises (disarmament commission, economic conference, etc.), just as he is the representative of French imperialism on the Executive of the Amsterdam International. His policy of collaboration with the employers and the State finds expression in the National Economic Council, an official ministerial organisation. Presided over by Poincare, controlled by big financiers with whom Jouhaux is connected, the National Economic Council forms the permanent organ of “industrial peace,” of “class solidarity” in France.

The programme of the C.G.T. is one of effective and active Participation by the reformist trade unions in the capitalist attempt at rationalisation and mobilisation; the C.G.T. has expressed itself clearly and openly in favour of rationalisation. In order to establish close collaboration with the capitalists, the machinery of collaboration must be created. That is why the C.G.T. is in favour of introducing and generalising in France the system of collective agreements between the reformist trade unions and the employers, compulsory arbitration, factory councils and workers’ participation in the technical management of the enterprises, which the C.G.T. calls “workers’ control.” This general plan implies of course, in a country where the trade union movement is divided and where go per cent. of the workers are unorganised, official recognition of the reformist trade unions by the State, and recognition of the bourgeois State by the reformist trade unions. Thus the C.G.T. is endeavouring to secure the integration of the reformist trade unions into the imperialist State, the extension of the National Economic Council into an economic parliament by a special article of the constitution.

This tendency towards the incorporation of the reformist trade unions in the state machine must inevitably lead to the destruction of the revolutionary trade unions. The reformist C.G.T. is itself directly interested in repressive measures against the C.G.T.U. and the Communist Party. It has managed to induce Government organisations to refuse to have any dealings with the unitary trade unions and has thereby secured for itself a clear field among functionaries, state employees and the petty bourgeoisie in general. Its membership has grown in the last year,—it has over 600,000 members,—but its social composition is taking more and more the form of an organisation of the petty bourgeois sections of the population.

A Left tendency, ideologically and organizationally weak, has developed in opposition to this policy, the general programme of which, issued prior to the elections, has been accepted by the parties which represent the big French bourgeoisie and by Poincare himself. The “Friends of Unity” with their small organ “L’Unite” succeeded in grouping around themselves a number of trade unions, and in developing fairly intensive propaganda in favour of trade union unity. But the platform of this opposition was a formal! and sentimental unity, lacking serious opposition to the entire collaboration policy of the C.G.T.

The Congress of the C.G.T. in 1927 showed the weakness and inadequacy of this platform. The Executive of the C.G.T. is endeavouring moreover to break up and expel this unitary minority

Although Jouhaux denies it, the general orientation of the C.G.T. has a strange resemblance to the programme of Mussolini’s corporations. He will no doubt evolve more and more in this direction if the big French capitalists find it profitable.

General Activity of the C.P.F.

In the course of its activity in the last few years, in spite of errors and weaknesses, the Party has progressed with its Bolshevisation by means of severe and repeated self-criticism, with the help and under the direction of the C.I.

Three main periods can be distinguished in the evolution and internal struggle carried on by the Party in connection with its general activity:

I. The Period of Struggle Against Opportunist and Social Democratic Survivals.

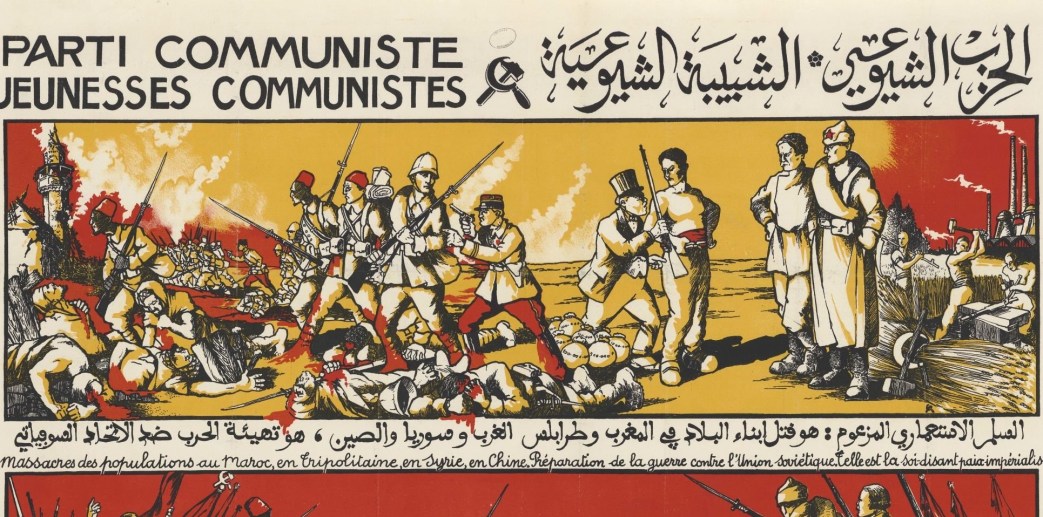

The courageous and politically correct campaign of the C.P.F. in the Moroccan war had a positive and decisive result in the internal life of the Party. It allowed the exposure of the group of opportunist elements represented by Paz and Loriot, who, together with the counter-revolutionary Souvarine, attacked the essential principles of Leninism in the fundamental questions of revolutionary defeatism, of support of the liberation movement of the colonial peoples, and who at the same time advocated as a sort of organisational outcome of their social democratic political conceptions, a reversal of the basis of the Party to the old form of local sections. In the course of this big ideological struggle the whole Party gained much experience with regard to the essential questions of Bolshevik struggle against war and imperialism, as well as with regard to the role, the conception and organisation of a genuinely Communist Party.

II. The Struggle Against Ultra-Left Tendencies.

The grouping around the opportunist elements of a certain stratum of discontented workers, the internal condition of the Party characterised by a regime of absolute centralisation and mechanical discipline, erroneous political slogans too far in advance of the Situation and of the masses, the isolation of the trade union cadres from the Party executive,—these factors induced the latter to engage in a struggle for the liquidation of this situation against those members of the executive who represented this policy. It was in the course of a conference held on December 1st and 2nd, 1925, that the Party began to liquidate this situation by correct but rather incomplete self-criticism.

The Lille Congress of the C.P.F. was to be a still more important milestone along this path.

III. The Struggle Against Trotskyism.

While the opportunist elements expelled from the Party were organising themselves outside in order to struggle against the Party, the old “Leftist” leaders, condemned by the Lille Congress, were organising themselves within the Party on the basis of the political platform of the opposition in the C.P.S.U. This struggle the primary object of which was to prevent the Party taking up a definite position, developed rapidly into a systematically organised fractional struggle headed by Suzanne Girault and Treint.

These facts brought the whole Party membership into the discussion in order to eliminate the agents of Trotskyism and their ideology from the Party. The characteristic feature of this discussion which was carried on in the sphere of international questions concerning the U.S.S.R. as well as in the sphere of the political problems confronting the French Pary, was that it allowed the whole Party to see and establish the true opportunist nature of those who endeavoured to disguise their fractional struggles by “Left” phraseology. This discussion was concluded at the national Conference in January, 1928, and Treint and Suzanne Girault were expelled from the Party.

These political struggles within the Party constitute one of the most positive results of the activity of the C.P.F. during the last years. The Party certainly progressed, but throughout this period, it committed many political and tactical errors and showed its weakness in many respects in the course of its general activity.

The Lille Congress in 1926 recognised the effort at political rectification undertaken in the Open Letter of December 1st and 2nd, 1925, which was directed towards remedying the Leftist errors of the Executive. But subsequently, in the face of the political failure of the Left bloc, of the regrouping of bourgeois forces in the National Union, of the support given by the Socialist Party and the reformist C.G.T. to the programme of the capitalists, the Party should have accentuated its tactics by strengthening its attack against these political formations, and by showing more clearly its revolutionary aspect. But throughout this period the C.P.F. made serious mistakes in its appreciation of the character of events and of the policy of the bourgeoisie; it was unable to adapt its tactics rapidly to the changed political situation.

It was this criticism on the part of the International, made repeatedly in the course of 1927, which the Party was induced to examined and express in the Open Letter of November, 1927. The determination to rectify the policy of the Party and to remedy a whole series of opportunist mistakes was carried to a conclusion at the National Conference in January 1928, and at the Plenum which followed it; decisions were made on both these occasions, which the Party proceeded to carry out.

The Big Party Campaigns.

The general activity of the C.P.F. has taken in the last few years the form of a series of big campaigns conducted against the Left bloc, its financial, economic and imperialist policy, and against its main support—the Socialist Party; against the National Union and its policy of capitalist rationalisation and preparation of new imperialist wars; for the defence of the U.S.S.R. and particularly for the Tenth Anniversary of October; against imperialist intervention in China and the danger of war; against imperialist repression; for Sacco and Vanzetti: for an amnesty; for developing the trade unions (trade union month of the Party); for international proletarian solidarity (campaign for the British strikers); finally, the election campaign against the National Union and its Socialist supporters.

Among all these campaigns one must single out the energetic struggle correctly carried on by the Party against the war in Morocco. For the first time the Communist Party drew workers, soldiers and sailors into an important mass movement (the Bolshevik struggle against war). The general strike on October 12, 1927, which roused nearly one million workers, the protests inside the army and navy, numerous cases of fraternisation between French soldiers and the insurgent Riffs, are the most important features of the best campaign carried on by the Party.

The agitational and recruiting campaign in the Autumn of 1926 which was directed also against the Left bloc of fraudulent bankrupts, roused tens of thousands of workers and added several thousand members to the Party. This campaign too can be considered a great success.

The Party’s campaign against the imperialist army Bill and particularly its struggle against the re-institution of the reserve periods roused enormous numbers of workers and peasants and the great bulk of the reservists who held demonstrations inside the army ranks under the slogans of the Communist Party. But, notwithstanding these positive results, the campaigns of the Party all have one common defect. Nearly all of them are campaigns conducted from above, by the central organ of the Party “L’Humanité,” by the Parliamentary fraction, with but a feeble participation of the basic organisations of the Party. As a rule they are excellent from the agitational point of view, but show great weaknesses in that the whole Party is not involved in the work of making full use of them by steady organisational efforts which would strengthen its ranks.

The recent big election campaign of the Party was certainly an enormous success. Taking into consideration the fact that it was fighting against all the other bourgeois and Socialist parties, that it was basing itself on a programme of proletarian demands closely connected with our fundamental revolutionary aims; taking into consideration its new tactic which was breaking for the first time with the old tradition of bourgeois republican discipline, the repression and the formidable weapons used against it, the success of the C.P.F. (a gain of 200,000 votes compared with the election in May 1924) must not be underestimated. This success is all the more important as it was achieved in the big industrial centres which had hitherto been under the influence of the Social Democrats. After this campaign the C.P.F. set itself the task of consolidating its success by systematic recruiting work for the Party and the trade unions, particularly in the big workshops of the basic industrial centres of the country.

Propaganda.

Apart from the subjects for propaganda with which political events and agitation campaigns supplied the Party, which the latter endeavoured to popularise among all its adherents, systematic propaganda was organised in the Party.

It is carried on in schools, circles and lately by means of self-education.

The Party circles can be divided into three main categories:

The central national schools (there have been none since January, 1926, but there will be again in the Autumn of 1928). These last two months. They teach the essential theoretical, political and practical doctrines of Marxism and Leninism.

Regional schools.—They last from 8 days to one month when they are full-time, which is very seldom. They last from 3-4 months when they are only in the nature of evening classes. They give systematic instruction in elementary Leninism; they are middle-grade schools.

District schools, which are always evening schools in Paris, and some times full-time schools lasting from one to three days in the provinces. They deal only with questions of principle connected with current events. For instance, the subjects recently dealt with have been as follows: Leninism and War; The Communist Attitude to Elections and the Bourgeois Parliament. But they always include a general elementary outline of our doctrine.

They are schools of the elementary type. Courses intended for exhaustive study of some special question are still in the experimental stage. The same may be said of self-education.

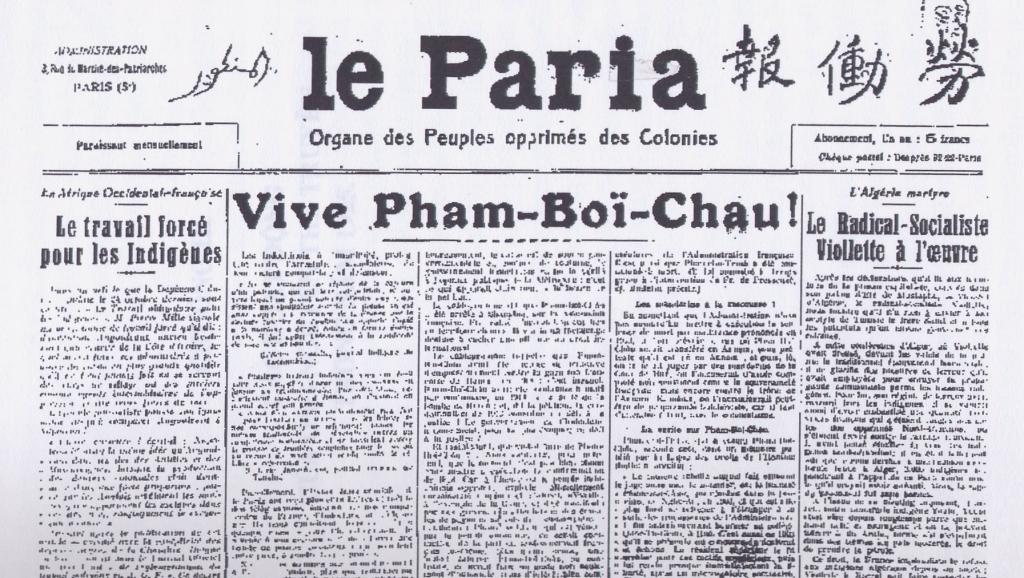

The Press.

The Central organ of the Party, “Humanité,” has a circulation of 220,000 which on certain occasions amounts to 350,000. On April 30, the day after the elections, “l’Humanite” issued 415,000 copies. (“Le Populaire,” the organ of the Socialists, has a circulation of only 60-80,000.)

“l’Humanite,” because of its big circulation, plays an important role in spreading the Slogans of the C.P.F. among the masses. However, it has frequently been guilty of distorting the political line of the Party, of which certain of its contributors have an erroneous conception.

Side by side with “l’Humanite” the Party has two other dailies with a rather restricted circulation; “l’Humanite” of Alsace Lorraine (15,000) and the “Depeche de l’Aub” (8-10,000.)

Generally speaking our provincial press is very inferior to that of the Social Democrats both in regard to circulation and technically.

We have at our disposal 25 weekly organs with an average circulation of from 2 to 6,000, and a weekly organ, “I’EnChaine du Nord,” with a circulation of 32,000.

A weekly “Press Bulletin” edited by the central Agitprop gives them their orientation with regard to current events and the campaigns in which the Party is engaged.

Socialist and quasi-Socialist papers have a big circulation in the provinces. They have on an average five to ten times more readers than our press.

Factory Newspapers and Worker Correspondents.

We have in France several hundred factory newspapers. Unfortunately most of them are edited directly by the regions or the districts, as our nuclei have not the necessary political and technical equipment.

Five months ago, at the tenth anniversary of October, “l’Humanite” launched the workers Correspondents’ movement which had not existed previously. It is steadily developing; every week a whole page of “l’Humanite” is devoted to it. Our provincial papers are following suit, but hitherto with very small results.

“Cahiers Du Bolchevisme.”

The “Cahiers du Bolchévisme” is the theoretical organ of the Party. Its circulation (3,600 in January, 1926) has been steadily decreasing (2,750 to-day.)

It has lately undergone a change, and has become a monthly instead of a fortnightly. This is all to the good, because it shows the determination of the Executive of the C.P.F. to make the “Cahiers du Bolchévisme” a genuine Communist review, which is very much needed by the Party.

Trade Union Activity of the C.P.F. and the C.G.T.U.

In view of the role played in the revolutionary trade union movement in France by active Communists, one cannot study the activity of the trade union organisation, the C.G.T.U., without at the same time taking stock of the trade union work of the Communist Party.

The trade union activity of the C.G.T.U. of the last few years can be divided into two big periods: the first, that of struggle against the consequences of the inflation policy of the Left bloc, which depreciated wages and worsened the economic position of the workers, The second, against the consequences of the currency stabilisation, the economic crisis, complete and partial unemployment, and the policy of capitalist rationalisation with, as its consequence, the employers’ vicious attacks on wages, on the 8-hour day and the general conditions of the workers.

During these two main periods, in all the movements connected with the class struggle of the workers, in the period of accentuated unemployment, at the end of 1926, in all the strike movements in which it took the lead, in its action of international solidarity support for the British miners), also by its steady struggle against the imperialist policy of France (struggle against the war in Morocco and the intervention in China, etc.), its campaign in defence of the U.S.S.R., etc., the C.G.T.U. showed itself clearly in the eyes of the masses as the only militant trade union organisation of the workers which refuses to enter into any agreements either with the bourgeois state or with the employers.

By its steady action for trade union unity, contrasted with the treachery and surrenders of the reformist leaders whom it continually denounces, the C.G.T.U. has placed itself at the head of the trade union movement.

And now, above all, when the class struggle is becoming more accentuated and the offensive of the employers and the whole bourgeoisie intensified, the C.G.T.U. must become more and more the centre of active and energetic resistance on the part of the working class. This is the situation which is at the bottom of the fierce capitalist campaign for the destruction of the unitarian trade unions, and of the increased repression of active trade unionists.

Nevertheless errors have taken place. They showed themselves very clearly recently, when the membership of the C.G.T.U., which had kept up round about 500,000, decreased considerably. This retrogression is particularly felt in the Metal Workers’ Federation which has lost over 10,000 members. Is this the consequence of a diminution of the influence of the Red trade union organisation? We do not think so, because we can see side by side with this diminution of the membership, a series of incidents showing on the contrary that the general influence of the Red trade unions is growing. There is, for instance, the case of the elections to the Supreme Council of Railwaymen, when unitarian delegates were elected who polled over 150,000 votes; that is to say 50 per cent. more votes than the total membership of the unitarian trade unions. The same was the case in the elections of the miners’ delegates in the East of France where 41 unitarian delegates were elected; finally, there were numerous successes in connection with the establishment of the united front (in almost all strikes, among railwaymen, on May Day.)

The causes of this abnormal situation in the unitarian trade union movement came to light at the recent meetings of the C.P.F., at the recent Plenum of the C.I. and also at the last Congress of the R.I.L.U. These are, first and foremost, the predominance of agitation over organisational work ; inadequate connection between the leading organs and the basic organisations and industrial enterprises; feeble work among the masses and absence of organisation of basic trade union sections. There is also a lack of direct objective in the work and inadequate concentration of forces in the baste industrial regions of the capitalists, as well as a certain underestimation of the repression of the employers and government, all of which has greatly weakened the struggle for trade union rights. Finally, there is a too theoretical manner of approach to the question of unity, and a failure to give it the character of a struggle for the workers’ demands. To these causes must he added the remains of reformist and anarcho-syndicalist survivals and, latterly, in certain cases, a spirit of passivity in the struggle against the employers’ offensive. The latter facts have had their practical repercussion in the very bad leadership of certain workers’ movements and in a habit of acting as a brake on the workers’ struggle.

These weak points in the trade union movement are closely connected with an inadequate realisation on the part of the C.P.F. as a whole, of the importance of trade union work, which is reflected in the errors and mistakes which have been committed, and also in the organisational work of the Communist fractions within the unitarian and reformist trade union movements. Thus, according to a recent census (which is far from complete as it does not include the Paris region) there are 349 Communist fractions in the unitary trade unions, 54 in the C.G.T. union, and 6 in the autonomous unions.

These weak points in the unitary trade union movement were already partly remedied at the time of the last national congress of the C.G.T.U. in Bordeaux. Since then the C.P.F. has been more critical of its trade union activity. The question is to be discussed by the whole Party and also by all the members of the trade unions. There is no doubt whatever that, provided the C.P.F. applies properly the directions given by its last national conference, by the Executive of the C.I. and by the Congress of the R.I.L.U., it will be able to improve the trade union activity of all its forces, and to increase thereby the influence and, above all, the organisational strength of the C.G.T.U., in order to draw the whole working class into the struggle against the capitalist rationalisation of the employers and the government of France, and into the fight for trade union unity. This is one of the most important tasks of the C.P.F. in its policy of rectification.

The Peasant Work of the C.P.F.

The activity of the C.P.F. in the countryside for the capture and organisation of large sections of the peasantry and agricultural labourers is very inadequate indeed.

Very little has been done with regard to propaganda inside the Party in order to explain the tasks of Communists in the countryside, as well as in general agitational and organisational work.

The result has been an almost complete absence of activity by the Party as a whole, confusion and theoretical errors among many militants, and complete failure to understand the importance of the agrarian question and of the practical tasks of the C.P. in the rural districts.

The Party looked upon work among the peasantry as a matter for a few “specialists” and for the French Peasant Council. Owing to Communist inactivity, the latter is a feeble organisation more inclined towards co-operative forms than to the broad organisation of an energetic peasant struggle against the big landowners and for unity with the working class.

Quite lately, the Executive of the C.P.F. has realised that this makes a serious gap in its work. It has decided to bring the agrarian question—Communist work among the peasantry—before the Party, and to open a broad discussion on the subject which will be concluded at the Party conference in June, 1928.

The aims of this discussion which the C.P.F. has decided to initiate can be summed up thus: to make the whole Party realise that peasant work must be carried on collectively by the whole Party in order to:

(1) Get the peasants away from bourgeois influence.

(2) Organise the defence of the interests of the various categories, of rural workers against their direct exploiters, against the bourgeois state and the whole capitalist régime, and to arouse the rural districts on the basis for the class struggle.

(3) Work for a genuine alliance between the workers and peasants, emphasising the fact that this alliance is an indispensable condition of their complete emancipation.

(4) Systematically intensify propaganda in the rural districts against the war danger.

(5) Demonstrate that the peasants of all countries are interested in defending the Soviet Union, which is threatened by the bourgeoisie, because the peasants there have seized the land and have definitely emancipated themselves from the yoke of the big landowners.

To achieve these aims, “at the bottom of which is the development of the class struggle in the rural districts,” the Executive of the C.P.F. points out the necessity to combat the error which makes militant members of the Party look upon the Peasant Council as the peasant organisation of the Party. To develop the Peasant Council into a genuine fighting mass organisation, this is the task which the C.P.F. has set itself in the present period.

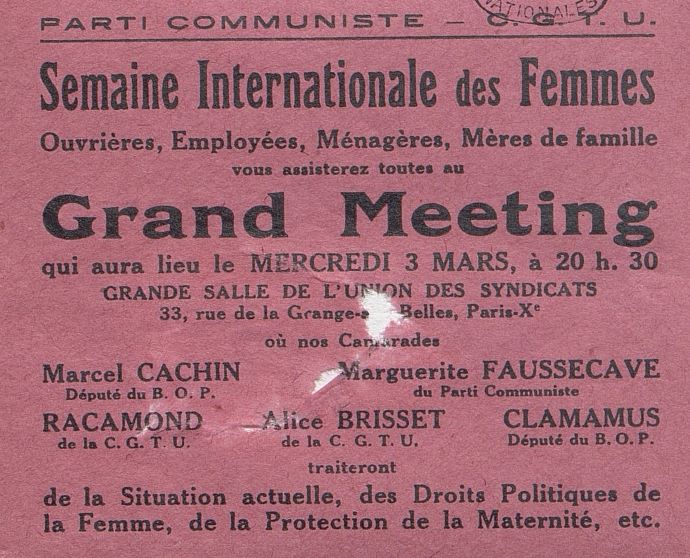

Work of the C.P. Among Women.

The practical work of the Women’s Department has been carried on mainly in two very important spheres where considerable success has been achieved.

Although the numbers are very weak, intensive work has been carried on in the Trade Unions (C.G.T.U.) for the organisation of women’s commissions in all important trade unions, including local branches and workshops, for the elaboration of a concrete programme-of-action for the various sections, for the organisation of the struggle for the workers’ demands, and in order to get working women to take on trade union duties and to elect the trade union and political education of large masses by means of working women’s conferences. After intensive preparation in the trade unions for two months the national women’s trade union conference took place in October in Bordeaux. It was attended by seventy women delegates properly elected in the trade unions. They discussed in a practical manner the effects of rationalisation on woman-labour and the organisation of the working women’s struggle. The women’s department has begun to organise such conferences locally and according to industries, drawing in women delegates who are not in trade unions or who are members of the reformist unions. These conferences must be transformed—as far as this is possible—into periodical delegate meetings.

In order to carry on the campaign against imperialist wars, and particularly in order to oppose the Boncour Law, which militarises the whole population, including women and children, the Party established in 1927 the Women’s Fraternal Union Against War. Within a year the Party was able to organise about 3,000 proletarian women in 200 local groups. Most of them are non-party, with a sprinkling of Socialists, and over half of the women are factory workers. Owing to inadequate ideological clarity inside the Party and to the numerical weakness of the leading Communist fractions in this organisation, its central committee surrendered too much from the beginning to the pacifist mentality of the women masses, and failed to point out the class character and the conclusions of the struggle against imperialist war. (According to its statutes the aim of this union is: Struggle against war and its consequences). This work can be considered successful in so far as it has for the first time organised the forces of the proletarian women and drawn them into activity under the leadership of the Party; that these women are beginning to give up their pacifist illusions and can become the framework for the mobilisation of big masses of women for the Class Struggle and for struggle against Imperialist Wars.

The Party has not been able to re-issue “L’Ouvriére,” which was suppressed a year ago.

The Executive and the Party give very little support to agitational and organisational work among women masses. The idea still prevails that this is the work of a department and not of the Party as a whole.

The Co-operative Work of the C.P.F.

The work of the C.P.F. in the co-operative sphere during the last two years has helped to clear up the question of our tactics in the co-operative movement.

A conference of active co-operators was convened in Paris in May, 1927. It laid down in its resolutions in a very concrete manner the tasks of Communists in the co-operative movement and the organisational measures to be taken.

Communist fractions are already functioning in a certain number of co-operatives. But it must be admitted that up till now these fractions have not carried on real mass work, but have limited themselves to considering and discussing the internal questions of their societies.

Co-operators’ circles have been reorganised on a new basis, but they are not very active.

Although our work in the co-operative movement is inadequate, a certain amount of success has been achieved which shows that our influence is growing. However, we cannot be satisfied with these results.

In the course of last year the first steps were taken to establish regular collaboration with the C.G.T.U. The Bordeaux Congress passed for the first time a resolution on work in the co-operative movement.

In the propaganda sphere the central Co-operative Commission took advantage of all opportunities to carry on a campaign amongst the members of co-operatives. The Congress of the F.N.C., the international congress of the A.I.C., and International Co-operators’ Day are always occasions for agitation.

The “Co-opérateur,” the organ of the circles, which contains varied and interesting material has already a considerable circulation. When special numbers have been published it has happened that as many as 20,000 copies have been sold.

Co-operators’ delegations have visited the U.S.S.R. The only delegation which was sent for the October celebrations was entirely composed of Communists and could not produce the desired effect. The composition of the delegation was not only due to inadequate preparation, it was the result of the smallness of our influence in the movement. For the same reason the meetings of co-operators convened on the return of the delegation were, with a few exceptions, not very well attended.

The Organisational Position of the Party.

The membership of the Party in no way corresponds with its influence among the masses. According to the last organisational conference the Party has 56,000 members, 17,448 (31.15 per cent.) of whom are organised in 898 factory groups and 38,502 in 2,110 area and street groups. With regard to the 898 factory groups one must distinguish: (1) administrative groups including 218 railwaymen’s groups with 4,467 members (7.9 per cent.) and 137 other groups (postal, customs, tramsways, municipal employees, etc.) with 2,503 members (4.5 per cent.); (2) factory groups pure and simple existing in private enterprises: mines (122 groups with 1,808 members—3.2 per cent.); metallurgic (212 groups with 3,300 members—5.6 per cent.); textile (56 groups with 1,083 members—1.9 per cent.) and others (153 groups with 4,288 members—7.6 per cent.).

This organisational weakness is due to a series of weak points in the work of the Party. Neither can it be separated from the political mistakes of the Party, subsequently remedied by the Party and the International, political mistakes and errors which were bound to have repercussions on organisation.

The last organisational conference had very positive results for the Party, it summed up past weaknesses completely and severely, and proposed a series of drastic measures for their elimination. This is how the conference described the organisational position of the Party:

“Apart from the errors committed by the Party in the political sphere, the inadequate organisational work of the Party from the bottom to the top is one of the most important causes of our lack of success. The error committed was the exact opposite of those of the last two years. At that time there was an inclination to judge all party actions from the organisational viewpoint, whereas to-day there is a tendency to deal exclusively with political questions instead of carrying on, parallel with our political work, the organisational work which is so necessary for the consolidation of our influence. We wish to point out the survival in many cases of mechanical work, of a lack of initiative, a tendency to await orders from above, and an absence of collective work. Generally speaking, our committees have proved unable to make the groups into the real basis of the Party. When dealing with the causes of lack of support of factory groups by the workers we allotted a big place to repression and the economic crisis. These two important facts, however, cannot explain completely the lack of success of our work, the reasons for which we must seek in opportunist mistakes and weakness in the internal work of the Party.”

A certain amount of progress has been made during the last period, notably in the reorganisation of the regions, the readjustment of the Party districts within administrative limits, and the creation of departmental committees. Progress must also be reported with regard to initiative at the base, notably in the struggle against repression, with regard to regular payment of membership dues and to a general improvement in the political activity of the groups.

The Communist International Between the Fifth and the Sixth Congresses, 1924-28. Published by the Communist International, 1928.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/comintern_between_fifth_and_sixth_congress_ao2/comintern_between_fifth_and_sixth_congress_ao2.pdf