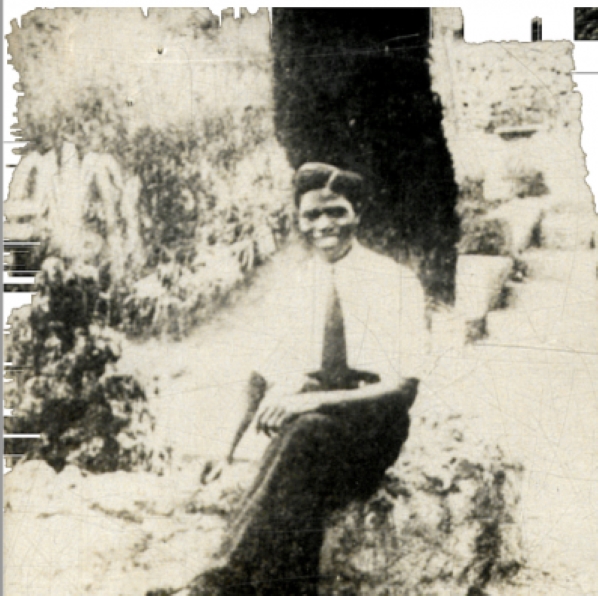

Tiemoko Kouyaté, a founder African Communism, on the R.I.L.U.’s campaign in defense of Black maritime workers in Europe. Born in Mali in 1902 and moving to France in 1924 to attend teaching school, he was soon expelled. Joining the French C.P., Kouyaté organized African mariners in French ports, established the Pan-Africanist League for the Defense of the Negro Race and edited its ‘La Race Nègre’ addressing the diaspora in France and its many colonies. The LDNR was a founder of the League against Imperialism in 1927, then led by another pioneering African Communist, Senegalese Lamine Senghor, who died shortly after. Tiemoko Kouyaté assumed leadership of the LDNR and was delegate for French West Africa to the second League Against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression congress held in Frankfort, Germany in 1929. Kouyaté would work closely with George Padmore and followed a similar trajectory, both being expelled from the Communist movement in 1933 for ‘nationalist deviations.’ Kouyaté remained in France, working as a welder, continuing Pan-Africanist political activity and collaboration with Padmore. Arrested during the Nazi occupation, Kouyaté died in Mauthausen Concentration Camp on July 4, 1944.

‘Solidarity Between White and Coloured Sailors’ by Garan Kouyaté from The Negro Worker. Vol. 3 No. 2. March, 1932.

Since three months the Unitarian Federation of Sailors and Fishermen, with the active support of the C.G.T.U., is carrying on in all French ports an energetic agitational and organisational campaign among the sailors and fishermen.

The preparation of the light of the sailors, on the basis of a united front against all wage cuts and against unemployment, demands the greatest vigilance of the revolutionary workers because of the new tactic applied by the capitalist war mongers and of the cynical manoeuvres of the reformist leaders, who are combined to divide up the ranks of the workers and weaken their struggles.

The reformist trade union leaders of France have sold themselves to the armament magnates and are participating in their war business.

It must be remembered here that at their trade union congress of Sept. 1931 they demanded, in a special resolution on employment, the priority of getting jobs for the French sailor and1 the repatriation of the colonial and foreign sailors. They thought that in this way they could regain the confidence of the white seamen who have been suffering so much by their treachery in all their economic struggles of the past. And they were especially out to break up the united fighting front of all seamen, by mobilizing the white against the coloured workers and the unemployed against those still lucky enough to have jobs. In their policy of divide and rule” they were of course supported by the administration of the Seamens Labor Exchange and by certain shipping companies among which the Company of the Chargeurs Reunis deserves special mention.

Terror Against the Colonial Workers

In Bordeaux the trade union bureaucrats, Durand and his clique, started a regime of terror against the coloured seamen: 14 Arabian sailors, 9 Indo-Chinese, and later 18 more Arabs and 14 Indo-Chinese were shipped back to their countries between Nov. 25, 1931 and Jan. 9, 1932.

These coloured comrades were replaced by white unemployed seamen, with the active support of the agents of the Chargeurs Reunis in Bordeaux.

Similar outrages occurred in Havre on a number of ships; although the dismissed coloured seamen had been serving the companies as long as from 3 to 11 years.

When the coloured seamen sent a delegation to protest to the director of the Chargeurs Reunis in Havre, this worthy gentleman said that he was only carrying out the instructions of a circular of the Ministry of Commercial Marine. It is thus obvious that the government, the social-democratic municipal authorities of the ports and the shipowners are all supporting the demagogic demands of the reformist leaders. I his becomes even more obvious when we quote from the answer of the Minister for the Commercial Fleet to an interpellation of the social-democratic deputy for Dunkerque, who was evidently annoyed that the unemployed Negro, Indo-Chinese, and Arabian workers were not being shipped back home quickly enough. The minister, after excusing himself for the delay by pointing out that his Ministery had not the necessary funds to “carry out a collective repatriation”, stated that he had undertaken steps for collaboration between all ministries concerned, namely, the Ministry for Interior, for Labour and for the Commercial Fleet, “in order to put an end to a situation which could not continue without detriment to the public order”.

So here we see mobilized against the colonial seamen the coalition of all the apparatus of capitalist exploitation, force and oppression.

Under the Leadership of the Revolutionary Trade Union

In spite of all attempts to sabotage and intimidate the Negro, Indo-Chinese and Arab sailors, they have come by the hundreds to the meetings of the revolutionary sailor’s union in Rouen, Havre, Dunkerque, and other French ports. They have fully agreed to support our programme on the basis of united front on board of the ships, in the preparatory Committees for the strike and in the unemployed committees of the ports. They have stood together with their white comrades on the picket lines. When partial strikes on various ships broke out; the colonial seamen in big bodies collectively joined the revolutionary seamen’s union. Such an active participation of the colonial sailors, such a readiness to get organized under the banner of the C.G.T.U. means the full condemnation of social and national chauvinism and the class collaboration policy of the reformist leaders.

The campaign of the Unitarian Federation oi Sailors and Fishermen which is the practical consequence of our conference of port and dock workers of the 27th of December has shown an undeniable success. The sailors are fighting comradely together on all ships where wage cuts are threatening. Our unemployed comrades, too, are demonstrating together in Havre, Rouen, Bordeaux and Sain-Nazaire. The possibilities for the rapid development of our union are becoming bigger every day. But it is important that the functionaries of our sailors’ or fishers’ unions should now also organize the unemployed or partially unemployed. Every meeting, small as it might be, must be made an occasion to consolidate our influence by systematically recruiting new members for our union. The meetings have no real value for us unless they help us to develop our organization.

We must keep up the close ties with our colonial comrades and entrust them with practical tasks within our organization. In this way we shall not only develop their understanding for economic struggles, but we shall also strengthen the united front between the white and coloured workers against wage cuts, against unemployment, starvation and against all ministerial decrees—the originators of which are in reality the trade union reformists.

The campaign of our Federation has made possible the gathering, irrespective of race and colour, of the seamen and dockers. This is a good step forward for the preparation of the World Congress of the I.S.H., where representatives from the imperialist countries will meet with workers from the colonial countries to discuss and plan their common class interest.

Let us work as intensely as possible for the preparation of that congress, the principal task of which will be the internationalization of the struggles of these two sections of the working class, the common interests of which are beyond the artificial frontiers of the capitalist countries

First called The International Negro Workers’ Review and published in 1928, it was renamed The Negro Worker in 1931. Sponsored by the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW), a part of the Red International of Labor Unions and of the Communist International, its first editor was American Communist James W. Ford and included writers from Africa, the Caribbean, North America, Europe, and South America. Later, Trinidadian George Padmore was editor until his expulsion from the Party in 1934. The Negro Worker ceased publication in 1938. The journal is an important record of Black and Pan-African thought and debate from the 1930s. American writers Claude McKay, Harry Haywood, Langston Hughes, and others contributed.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/negro-worker/files/1932-v2n3-mar.pdf