Balcomb Greene, himself a politically-committed abstract artist and a leading proponent of the school in the U.S., reviews the 1936 MOMA exhibit, Cubism and Abstract Art.

‘Abstract Art at the Modern Museum’ by Balcomb Greene from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 5. April, 1936.

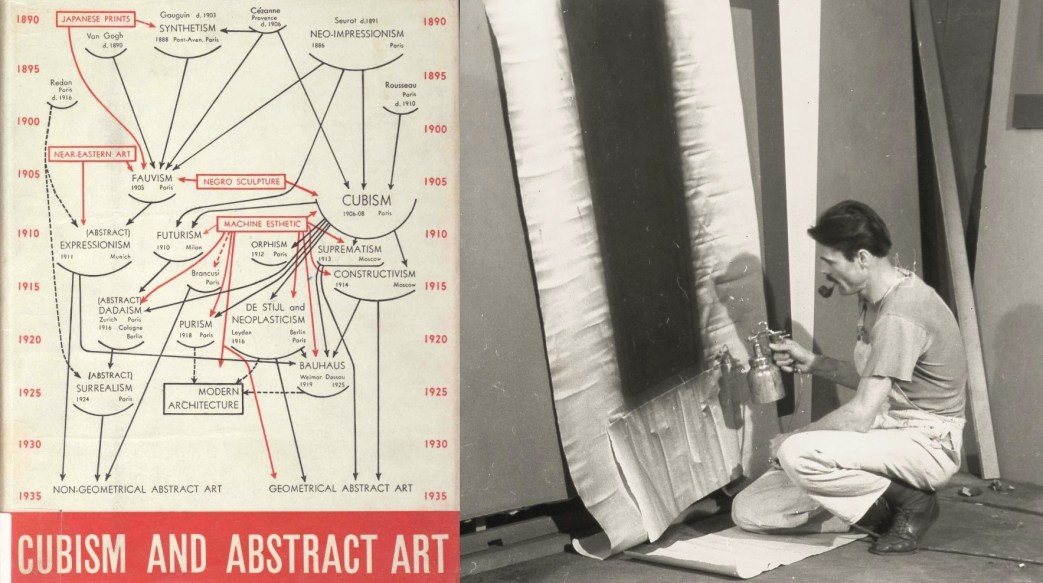

The exhibition now at the Museum of Modern. Art traces the development of cubism and abstract art, and indicates their influence upon the practical arts. The material on view includes painting, sculpture, architecture and furniture, photography, posters, typography, films and theatre designs. With an historical development so well presented, our interest is less in the intensity and quality of individual “art” expressions than in deciding what the function of the artist in society may be.

The arrangement of the show, starting with samples of cubist pictures on the first floor, and passing to the fourth floor where the completely abstract paintings and the “practical art” by-products of abstractionism have been shown us, is calculated to pose certain questions for the visitor. There is the old one as to how modern art ever got started, the equally hoary question as to what the effort was mainly, then the question which is answered with more difficulty—why did modern art culminate in the abstract?

To answer these questions there is no substitute for looking long at such exhibitions as the present one. Yet even the novice will see that, from the first to the top floor, there has been a sort of logical progression. By “logical” we do not mean that each successive movement can be drawn from the previous one as neatly as a rabbit from a hat. What is apparent is that the cubists made devilishly complex patterns which were distortions of people, landscapes and objects. These same artists later, abetted by newcomers, gave up representing objects. Each artist made this change in such an individual way that the purposes look different. One of the most common of tendencies was toward simplification. The usual way for the artist to simplify, get his work under control and make it distinctive was to limit himself to a type of form or shape and relationship. Delaunay and the orphists, whatever their theories were, reduced painting to brilliant pattern-making. Whether their pictures moved people or not, they weren’t confusing. After them the suprematists, led by the Russian Malevich in 1913, limited themselves to simple geometric forms, fewer forms but usually more varied than the little blurred areas that the orphists began using a year earlier. Leger and Ozenfant are largely responsible for the first pictures which achieved a machine movement. Looking at their pictures of this date, the eye performs a pleasant mechanical journey, usually ending up at the point on the canvas where it started. This was simplifying the problem of painting by making its purpose concrete. But at this point the question of simplification merges into the question of purpose.

We like to think that the purpose of a painter, whose innovation we admire, was always clear. We say that Cezanne was a pioneer of “plastic qualities”— which as a term used to be a catch-all to indicate a disinterest in the imitation of nature and an interest in canvas, plus its shape, plus paint—as ends in themselves. Whatever that means. We, and the cubists, became facile enough to say that plastic qualities in a painting guaranteed a preliminary emotion. Every emotion, likewise, guaranteed a concrete existence. Good old Cezanne! We couldn’t get beyond him! But the cubists began to explain themselves variously as seeking to “simplify the objective world”; “make the particular object universal”; “give a truer vision of the world through a more personal one”; and “rule out the personal as needless distortion.” They also attempted, in the words of their faithful theorists Gleizes and Metzinger, “to move around an object to seize successive appearances, which, fused in a single image, reconstitute it in time.” Clear enough as a purpose, problematical in its effect.

Perhaps it is only safe, in view of their own testimony, to say that the men who started as cubists were breaking down the pictorial conception of the objective world, and that they chose to call their procedure analytical. This doesn’t mean that the first abstract picture was an accident. But its intention may have been no more clear than that of those innovations, now extinct, such as orphism and dadaism—the former of which reduced the cubist problem of construction to child’s play, substituting an interest in the exploitation of color intensity, the latter of which facetiously and then woefully sought to deny the value of painting altogether. Today we like to say that the affirmative statements were more useful. Yet the futurists’ noisy manifesto for an excess of motion and Jeanneret’s worship of the machine are not negated, as influences, by many of the former becoming fascist converts, and the latter becoming Le Corbusier, the architect. All who contributed to the fervor for experimentation, and who boldly exploited even the possibilities of accident, were valuable men. Among those who failed we should list rather men like Matisse who followed a tradition downwards and, partly because he lived so long, became a pleasant pattern-maker, after the original makers of patterns had died.

Because the artists were men, instinct turned them back after every vigorous sally into the unknown, to a reliance upon forms and colors deriving their significance from an essential, but not obvious, resemblance to the items of the natural world, The transition to abstractionism from what was, relatively, a cubist dogmatism, we may most readily attribute to human instinct. The experiments were guided by the elements implicit in the character of all artists, explicit in ee growth of the individual, and contained finally in every work of art which is satisfying. The reference is to those two impulses which we may regard as the expansive and the restrictive, of the urge toward freedom and the urge to consolidate this freedom through some sort of formal discipline.

Each movement within abstractionism which was distinct enough to have had a special name may be best understood as a check upon all others. This will be true whether we are concerned with the complicated excesses of futurist theory or the uncomplicated excesses of neo-plastic practice. Beginning, accordingly, we may note the especial contributions of the constructivists working mainly in Russia, and of that loosely formed brotherhood of painters in Paris, now to be referred to as abstract surrealists—groups having much the character of opposites.

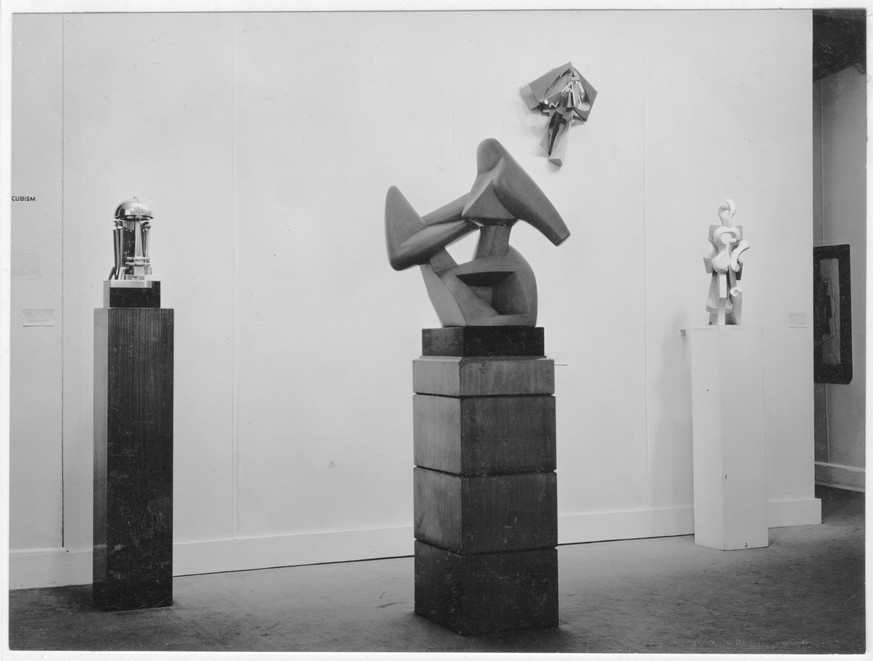

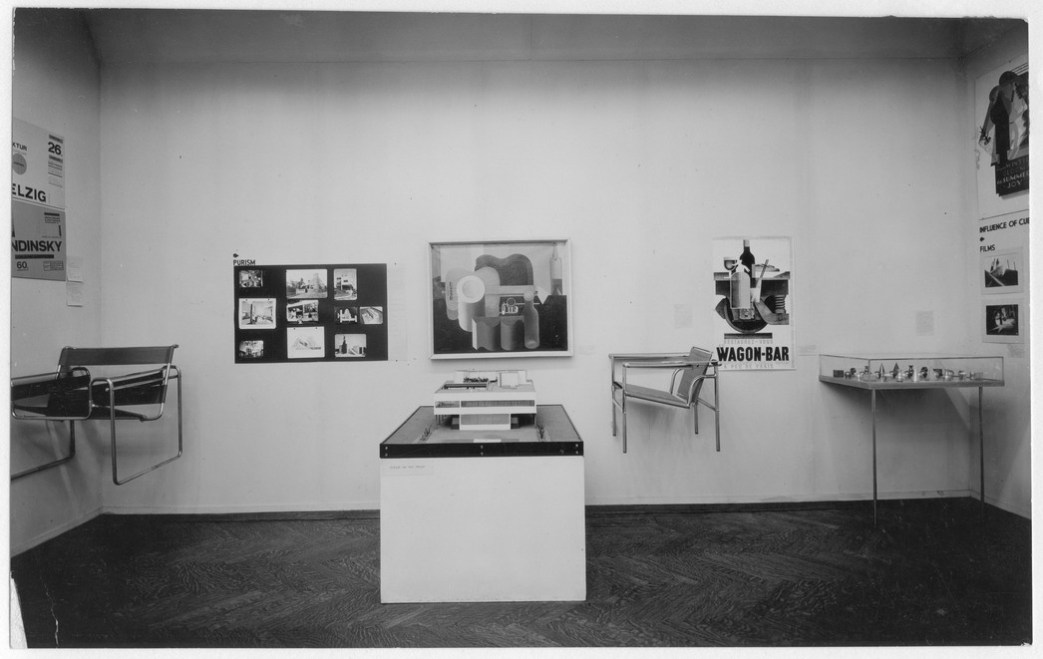

The idea which so enamored Vladimir Tatlin in 1913 that he founded a movement, was briefly, that each piece of sculpture should be made up of materials so selected, so shaped and so attached to each other that the piece would have no more excess weight or detail, and no more inconsistencies, than a good house or a good tool. The movement was pretty much confined to sculpture, although Tatlin and Lissitsky themselves painted. The question of purpose of a piece of sculpture Tatlin chose not to answer by theory. His unique contribution was the thought that the purpose of any piece of art could not be separated from its structure. The function might determine the way it was built, but, conversely, the function was determined by the structure. In the present exhibit the construction of Gabo, titled “Monument For an Airport,” made from glass and metal planes, may be taken as an adequate illustration of the point, assuming that glass and metal are appropriate to the subject of aeronautics, and assuming that the planes, as put together, are most serviceably to be composed of glass and the particular metal used. The “Realistic Manifesto,” published by Gabo in 1920, is virtually an application of the dialectics of materialism to the problems of the artist. Abroad, a similar “functional viewpoint” was being offered in Germany by Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian ex-lawyer. Cooperating with Gropius at the Bauhaus, he is responsible for introducing into the advanced industrial world of Germany a more sensible and economical tradition for machine construction. The steel implement, whether a drill or a vehicle, was often built, prior to this date, with almost the exact proportions as the making it of wood might have necessitated, and it was decorated by the scrolls and jiggers traditional to an ornamented manuscript.

The principle of constructivist economy may be taken as typical of the effort of artists engaged in experimentation to discipline their efforts. It is only because art is not a cut-and-dried business, but is incalculable in many of its effects, that the more imaginative work of Miro and the early Kandinsky may be looked upon as indispensable. Miro’s method in accumulating his interesting and provocative shapes might be termed less conscious or, if one likes the word better, intuitive. Such intuitive vigor, unless held in check, makes often for capers on canvas top personal and insufficiently organized by the usual rules of composition, to be effective; just as the work of the constructivists, in practice, limited itself most entirely to a play upon the laws of physics such as tension, balance, resistance and gravity, at the expense of what we term the more human emotions. But between being ineffective because one’s work is anarchistic and personal, and being ineffective because one’s work is mechanical and cold, there is scarcely any choice. Between such extremes the future course of abstractionism is obliged to chart itself and proceed warily because it is unable to fall back upon the easy imitation of nature. In the difficulty of balancing—or integrating it might be better to say–the intuitive with the rational, the particular with the general, the personal with the impersonal, and the expressive with the structural, lies naturally enough the source of power. When Mr. Barr, director of the Modern Museum, remarks that in ruling out connotations of subject matter, such as the sentimental, documentary, political, sexual and religious, the painter indicates a preference for purity at the expense of impoverishment of his possible range of values, he is either in error or we misunderstand him. The limitations placed upon an artist by himself are not an impoverishment, if the purpose of the artist is, as we have always understood, profound rather than extensive.

The question suggested by the present exhibit as to what ultimately the painters were after is best answered by considering how modern art got going in the first place. A revolt against the insipid taste in the academies, so they say. But were not all the ancient movements precisely this? What distinguished the new revolt from the cubists onward, was its violence and thoroughness. With the public still choking over the outrageous Cezanne, the artists in Paris solemnly pronounced the good apple painter a beginner. The violence, recklessness, despair, and even the facetiousness of what seems to be second and unprecedented stage of the revolt, can only be understood when we consider what the artist’s position in society at that date had become.

He had become declassed. After the industrial revolution, the balance of power had been shifting to the middle class. In the new sweeping democratization the artist stood revealed because of his personal attitude, because of his painting traditions, and because of the conventional attitude of the public toward him, a figure left over from feudal centuries, a skeleton endured by people because he was amusing or seemed to be suffering an excruciating and mysterious passion.

He could survive only by establishing a serviceable relationship to the class accumulating the balance of power. But the new middle class was impossible as patrons. First, because, lacking any taste of their own, they aped in an embarrassed way the taste of a defunct aristocracy. Secondly, they were not rich enough to assume the flourishes or build the collections traditional to the patron. Finally, the dominant man produced now by society was a specialist, a trained man committed to useful work, essentially a Puritan with an enquiring mind, tolerant of calendar pictures in deference to the misses who were affected by them because they were supposed to be useless; but most of all, and proudly, he was anti-beauty. He could not tolerate the man declassed by centuries of private patronage.

The newly rich, a bastard aristocracy not thriving until our times, simplified the difficulty of being patrons and vulgarized it by giving birth to the thoroughly illegitimate middlemen of art—hired tasters, enthusiasts at a percentage, and society-art promoters, attached, respectively and par example, to the Herald Tribune, the John Levy Gallery and Mrs. X’s boudoir.

They were not pulling a stunt, those few artists with guts who, in 1905, precipitated a second and violent period of the revolution which is art. From their garrets in Paris began to descend those amazing manifestos of purpose and sometimes lack of purpose, which showed clearer than anything else that the authors were men unclassed, drawing much of their enthusiasm from saying, “To hell with the public!” They refused to be prostitutes, they were regarded as clowns. And, as clowns, not often willing ones, not being paid well, they were often introverts. They were uniquely free, their daring out of bounds, even out of bounds of a clearly established purpose.

Therefore, this question is framed for us: Just how did the abstract artist, in formulating his new art by which to build experiences for people, help himself toward a more vital and tangible relationship with society? Part of the answer must be in his becoming a specialist. But the full answer is contained in his recognition that the specialist’s dictum is right; that the specialist must not be servile to tradition ; and that the economy dictated by industrial society could not be violated. In short, he became a materialist. Being a man without position in society, he first dissected the vitals of his art to find its significance and potential significance for himself, then ended with a willingness to build a new art starting as humbly as the mechanic who assembles his pulleys, steel plates and rods preparatory to building a machine. He denied the difference commonly held to exist between what is useful and what is artistic. The partial evidence of this is seen in such men as Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy developing new commercial serviceability for photography; Doesburg, Le Corbusier, Lissitsky and Rietveld bringing a new practicality to architecture; Leger, Lurcat and Picasso designing such common objects of use as rugs and furniture with their pleasantness inseparable from the utility; and, finally, Rodchenko, Cassandre, Grosz, and Gropper, bringing to commercial advertising and to political advertising or agitation a new effectiveness. The effort was in no case to add prettiness to the practical arts, but first to define their utility in terms even of the potential and then to devise corrections which would make decoration and other irrelevancies impossible. It is not by any accident that the men who removed beauty as a servile afterthought from the applied arts, also removed beauty as a servile vassal to ignorance and tradition from the fine arts.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n05-apr-1936-Art-Front.pdf