Giacinto Serrati attended 1920’s Second Comintern Congress in early 1920 and then traveled north to visit Petrograd, the epicenter of the Revolution, and wrote these rich impressions.

‘Letter from Petrograd’ by G.M. Serrati from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 14. October 2, 1920.

ONE cannot learn to know a great city like this in four days, not even as a “tourist”, in normal times, with every facility at one’s disposal. Let us not even pretend to know and interpret its spirit, to perceive its intimate sensations, to appreciate its virtues, or criticize its vices or errors; especially if one does not know the language perfectly, and is unable, therefore, to grasp a situation as expressed in the words of the people, in their exclamations, their songs and even in the graphic manifestations along the roads or in the public places…manifestations very eloquent in their naivete.

The journalist who passes and judges, who makes literature and proves a theory, is not a chronicler, still less a historian. The only eager readers of Barzini1 are those who are ignorant of what he writes and of the facts. He who knows laughs at him and sees in his prose only an object of mockery. There is not a soldier from the trenches who holds in the least esteem this narrator or the journal which opens its columns to him.

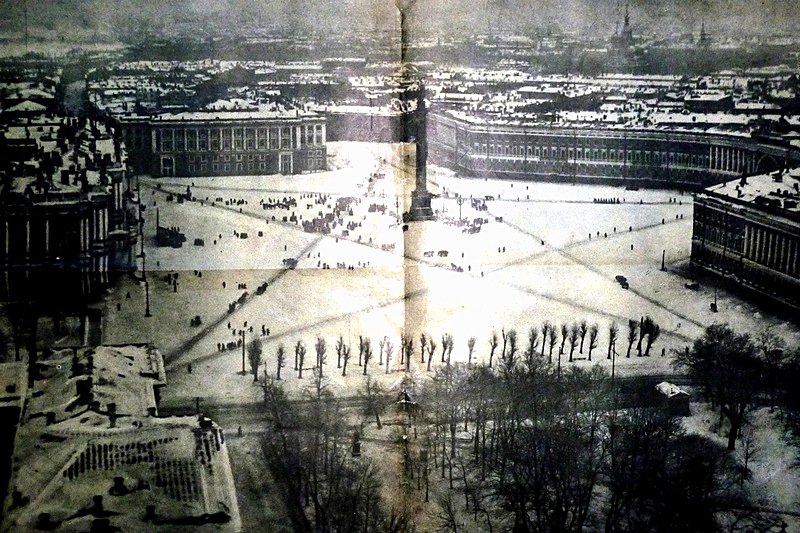

Only the ignorant, or fools, travel through a country in revolution with pencil and notebook and pretend to pass judgment upon it. To arrogate to one’s self the right to point out errors and indicate the road which the army of citizens sans culottes should take in order to gain time and hasten their epic, is ridiculous. I do not investigate, nor examine, neither judge nor criticize; I feel. In the past a long history of centuries of prostration, of humility, of slavery and tyranny, of violence and absolute, irresponsible personal power. Every street, every square and palace, recalls the living memory of a time when one commanded and one hundred and twenty millions obeyed. In the present, a people who, ten, twenty, a hundred times a day sing the glory of the Internationale of Labor with a quasi-mystic fervor of social renewal. Where people fell stricken by tyranny, behold, the debut of the renaissance inspired by the communist spirit. This is a great thing.

Grass has grown between the paving stones of several streets in Petrograd. The city which at one time had two million inhabitants has today not more than 700,000 or 800,000, perhaps. I have seen Paris when the German Bertha hurled its projectiles against the French capital. In a few days the joyous city became funereal. In those terrible days there were no crowds except at the railroad stations, and in the trains which bore away the terrified inhabitants. The P.-L.-M. was taken by assault. To fly to Marseilles, to the Cote d’Azur, was to flee death and seek life. Now, after six years of war, when three armies halve menaced its gates, when it has experienced two revolutions, and has had only yesterday to deprive its factories of those able-bodied men who remained at home, and of women and young people, to throw2 them, armed rather with heroism than with rifles, into the battlefields of Gatchina and Tsarskoe-Selo before the white armies of Yudenich,—Petrograd cannot give any thought to its own toilette. There is grass in its streets…there has been blood also. It cannot be otherwise in a revolution.

Yesterday, when my comrade and I visited the Putilov factories, and they asked a number of trifling questions of the engineer and the workers who accompanied us, I kept back. The questions seemed to me simply superfluous. In the immense factory—one of the three or four largest in the world, although it is not very well organized—from forty to fifty thousand workers were employed before the war. Today there are only a few thousand–mostly children, women and old people. The rest are soldiers at the front. Communists first. Scarcely has one entered the factory before he receives the impression of almost absolute cessation of life in this colossal body. Only a few puffs of thin smoke rise from an occasional chimney. A few blows of a solitary hammer resound through a hundred shops, the grinding of wood is scarcely heard from a few fraise machines. A few workers, mostly women and children, gaze at us with wild, curious eyes. The great, powerful pestle hammers are silent; the cranes with their immense nervous arms of steel are motionless; high furnaces are extinguished; the great rolling-mills, which can seize the red-hot iron in their steel claws and force it to bend in their powerful grasp, are in disuse and rusted. The many sounds of clanging steel, the roar of the foundries, the rolling of the pestle hammer, in the midst of millions of sparks and the ardent fires of a thousand flames, have yielded to a silence as of the grave—and the cawing crows pursue one another from iron truss to iron truss—and sometimes one hears the song of a bird, a veritable defiance.

In the back of the shop they are still repairing railway carriages; farther on four great locomotive boilers are only waiting for coal to be finished; another shop has already several cannon to be transported to the Polish front; they can still be manufactured here, the special steel necessary being abundant; but they are best manufactured at the place to which the manufacture of war material was transferred at the time it was feared Petrograd might be taken.

Other factories, one for cotton hydrophil, gauze, bandages, and other articles for sanitation, the other for caoutchouc, are working almost maximum. The central electric station is operating satisfactorily. But all the furnaces use wood fuel, so that the work is not very rapid, and industrial activity is reduced. On the other hand, the departure for the front of almost all the best workers, the great suffering due to insufficient food supplies, have deprived the remaining working masses of the zeal for work which they might have had, and which would not in any case be very great among people with the characteristics of the peoples of the Orient. Our Southerners, in comparison with the philosophic apathy of this Russian population—calm, serene, apathetic, slow even amidst the thousand tortures of the war, the revolution, and the blockade—appear to me today to be a most active and energetic people.

This native indolence of the Russians partly explains the grave difficulties which our Bolshevik comrades must encounter in the industrial reorganization of the communist society, and makes necessary the supremely grandiloquent proclamations of the governors. They employ the grand manner to overcome such apathy. I have seen posted in the factories a placard depicting an enormous, extremely repugnant louse, and beside this terrible parasite, Death, with his usual attribute, a scythe. Among us the ordinary proclamation of the mayor is sufficient to advise the population that they must take necessary hygienic measures to prevent the spread of disease epidemics. Here they need enormous signs, grand speeches, bold expressions. It is only thus that one can overcome the tendencies which naturally impel the Russian to the contemplative life.

The war, the revolution, and the suffering arising from them have doubtless accentuated this Mussulman spirit of the Russian people. In a country where the day is sufficient unto itself, and where the situation changes, or may change, so easily, where uncertainty prevails, it is very natural that the inhabitants should not give special thought to the morrow and that the gravest preoccupation should be that of satisfying the most urgent and immediate needs.

This only emphasizes the merit of the work which is being accomplished by our comrades who—very few in number as compared with the great magnitude of the work—are working actively for reconstruction.

Together with Comrade Zorine, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Petrograd, which has about 35,000 adherents, we visited the rest homes for men and women workers who needed pure air, good food, and complete rest. These houses, built on a verdant island in the middle of the Neva, in the most delightful section of Petrograd, and which were formerly resorts for the pleasures or debauches of the Petersburg bourgeoisie and aristocrats, were, at Zorine’s suggestion, rapidly transformed into health homes for the workers. They are magnificent villas in the midst of the verdure, with ample terraces, large stained glass windows, and enormous bays, tastefully decorated; some of them are furnished with real artistic sense, others in the worst bourgeois taste.

In the entrance of one of them we saw a collection of eight magnificent Flanders tapestries, old gifts of Napoleon to some Russian Duke or Prince; their price is placed at eight million francs. I pass over in silence the furniture of incalculable value.

In these villas, amidst the most dazzling luxury, men and women, two and three in a room, who have hitherto lived like beasts of burden in the murderous factories, take their rest. They come here in turns—upon designation by the organization committees—and spend about a month in complete repose. They scrupulously respect the property, now become collective. Whatever the localities visited, everywhere was the greatest cleanliness, order and tranquility. Each in his room, or in the common rooms, and wearing their plain working clothes, men and women live serenely in these halls, on these divans, amidst the splendor of the pictures, the mirrors, the objects of art and luxury, as if they had lived there all their lives.

I asked an old woman tobacco worker who has been employed in the factory for more than forty years: “How did you get used to such a life?” “Eh! Comrade, when one is well off, one gets used to it quickly!”

For them Communism is somewhat like the first taste of revenge. Formerly the masters were there. It is just that the workers should be there today. This easy turn-about in the infantile spirit of the working masses was, moreover, easily affected, as soon as the communists overthrew the old regime. The villas are there, the proprietors fled; it is not at all difficult to organize in these pleasure resorts—formerly the dwelling-places of pleasure-seekers, some of them the nouveaux riches of the war—communal life. In the last analysis it is a question only of consumption. The consummate is easy. It is true that the former inhabitants no longer produce. But—now that the revolution has abolished the masters, that is, those who could make others work for their own well-being—will the Russian working class be able to find within itself, in its energy and its own virtue, the power to produce, with the incentive of its own collective interests, as much as it produced formerly for the benefit of its exploiters?

That is the very grave problem. In the letters which are to follow we shall examine the program by which the Russian Communists are seeking the solution.

From Bulletin Communiste—Paris—No. 25–August 19, 1920.

NOTES

1. Correspondent of the Corriere delta Sera.

2. In the text is the word, “cacciarli”…to push, chase, impel—which does not correspond to the context or the general thought.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1923/v03n19-feb-22-1923-Inprecor-yxr.pdf